The winds cut sharply across the steppe in Arkhangai, despite the clean, hard light of the springtime sun that warms the backs of Namchin Batkhuu’s goats. It is still cold in this part of Mongolia, an eight-hour drive west from the capital, Ulaanbaatar, but he’s gambling that his goats can bear it just a few more days or weeks, until the temperatures start climbing. He’s cold and tired, but he doesn’t want to lose his window to maximize the profits of the only commodity he has, the one that will sustain his family for a whole year, so he presses on.

Crouching in a little wooden shed behind his yurt, Batkhuu grabs one of the last of his 600 goats, snuggling it close to him, and begins to comb, firmly but with a soft touch, loosening the featherlight undercoat from the groaning animal. “If you do it gently, it is like giving her a massage,” he says with a laugh. The silky fluff he pulls off in tufts is the world’s finest cashmere, raised in one of the most hardscrabble environments, and destined for some of the biggest luxury brands in the world.

But as he combs, Batkhuu is still working over his decision to harvest now. “You must be wary of timing,” he says. “If the combing is done too early, the goats can get sick from the cold; if you wait too long, they start shedding their undercoat and the product loses value.” Sudden snowstorms, even in May, are not unheard of in Mongolia: “You can’t predict politics, nor spring weather,” goes a Mongolian saying.

That night, snow begins to fall in Arkhangai. By morning, it has turned into a full storm, a whiteout of wind and ice sweeping across the steppe, erasing the roads. Within hours, the landscape is buried under the snow. The first green shoots vanish beneath the frost, and herds scatter in panic. When the sun returns the next day, herders set out to search for their animals across miles of frozen plains. For those who had already combed their goats, it is a tense and anxious search: The cold can be fatal if the goats don’t have their warm undercoat. A single storm is capable of wiping out an entire family’s livelihood.

In such unforgiving conditions, timing — when to move herds, when to shear or comb animals — has always been crucial for Mongolian herders, who have moved animals across the steppe for hundreds of years. But cashmere has pushed the stakes higher.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Mongolia’s herding economy opened to global markets. Demand for cashmere for export skyrocketed and the country quickly emerged as the world’s second-largest producer after China. It soon became one of the country’s top commodities, second only to minerals among Mongolia’s exports. Once a buy-it-for-life luxury accessible only to the few, a cashmere sweater soon became a cozy staple in the wardrobes of millions of consumers who could scoop one up in just about any mall or high street shop come wintertime.

Today, Mongolia collects about 10,000 tons of raw cashmere annually, six times what it produced in 1993. In the span of a single generation, herders pivoted their whole livelihoods toward cashmere. Before the boom, they had sold meat, dairy, artisanal products and the wool from sheep and yaks; the goats, more suited to the steppe further south in China, were a rarity. Now, for most herders, it’s cashmere or bust.

But even with seemingly insatiable demand for the soft, warm fiber, Mongolia’s herders are on the brink. The grasslands that once supported thousands of families with herds of yak, horses and sheep have been ravaged by the roughly 22 million cashmere goats that herders keep to meet market demands. The intensification of goat herding has caused overgrazing and accelerated soil degradation. In the span of just 30 years, cashmere has turned into an ecological disaster for Mongolia.

The crisis hasn’t escaped the notice of consumers, many of whom have their conscience pricked by buzzwords like “sustainability,” and has left brands trying to find a way to meet demand for both their goods and for a kind of moral uprightness around them. Into that space have come several organizations that claim to certify cashmere as “sustainable,” a squishy, ill-defined term that can touch on issues ranging from wages to ecology and animal welfare.

Among the cashmere certifiers, one company, Sustainable Fibre Alliance, has positioned itself as the conscience-assuager of those buying Mongolian cashmere from top-tier brands. Established in London in 2015, the SFA promises to deliver “sustainable cashmere” to its partners, with guidelines supposedly addressing issues all along the supply chain: biodiversity and land use, animal welfare, decent work for herders, and an improved fiber quality for brands and consumers. Among its founding members were producers of high-end cashmere garments, including Burberry, Johnstons of Elgin and Kering, the luxury fashion group that owns more than a dozen high-end brands, among them Gucci and Saint Laurent. Its current members include U.S. household names J.Crew, Doen and Madewell.

On its sleek website, the SFA touts its tough-but-fair demands of the herders whose cashmere it certifies. Along with maintaining animal welfare standards, they must conserve “natural habitats and biodiversity” on the land they use, identify “degraded areas that are used by their sites” and take “measures to avoid the introduction of alien species” to the steppe, among other things.

Yet on the ground, the picture looks very different from the values the SFA promotes to brands and consumers. New Lines traveled to the Mongolian steppe to speak with herders, traders, ecologists and government officials. Their accounts reveal muddy supply chains, self-certification, dwindling grasslands and herders struggling to survive, despite producing one of the most coveted fibers in the world.

Inside their yurt, Batkhuu and his wife, Orkhontuya Jamnyan, calculate this year’s cashmere production. From their 600 goats, they managed to obtain 550 pounds of cashmere fiber, which they sold at 62,000 tugrik — about $15 — per pound, for a total of around $8,700. For a family like Batkhuu’s, this sum represents almost the entirety of their annual income. It will have to stretch through the year to cover the cost of food, health care, fuel for transport and heating, hay and medicine for the livestock, and their children’s education.

Under the Soviet system, herders worked within state-managed cooperatives, with their livestock numbers strictly regulated — a sharp contrast to the freedom and pressures that came with privatization. With the transition to a market economy after the fall of the Soviet Union, Batkhuu’s family, like many other Mongolian herders, abandoned the cooperative model of livestock farming. Until then, the animals belonged to the state, and each family managed a limited number of heads. With privatization, pastures remained public, but the livestock became private property. This change pushed herders to multiply their herds.

“My mother had no more than 70 goats, among other animals,” Batkhuu explains. “Today, we have 10 times as many, and we heavily depend on cashmere. Goats are fragile animals, difficult to raise: When they’re born, they can’t walk on their own, and in winter they risk freezing to death. It’s a job that requires exhausting labor.”

For over 10 years, the family has been part of Dashdondog Erdenebat, a large cooperative certified by the SFA, which touts “decent work” and better access to the market for herders among its priorities. Yet their lives remain marked by the same persistent difficulties. Every year, they must take out loans to cover basic expenses, without knowing how much their cashmere will fetch or whether they will be able to repay their debts.

“All Mongolian herders are trapped in debt. I feel abused by the price of cashmere,” Batkhuu says. “It is unpredictable from one year to the next and never rises enough. Every year we are forced into debt to buy hay and medicine for the animals, especially with these ‘dzud,’” he adds, referring to the increasingly harsh and unstable winters.

In 1996, a pound of cashmere was worth just 5,500 tugrik — less than a dollar at the exchange rate of the time. By 2007, it had risen to 20,000 tugrik. Today, it exceeds 330,000 tugrik, over $100 per pound. However, inflation in Mongolia has also grown, fluctuating between 8% and 15% per year. In real terms, herders’ purchasing power has not improved significantly in a system where the business risk falls disproportionately on them.

“I have no idea how much my cashmere is sold for in Europe,” Batkhuu says. Like most commodities, profits aren’t evenly distributed along the supply chain; even within Mongolia, the price exporters receive for refined fiber is eight times higher than what herders are paid for the raw material.

Batkhuu inherited the trade from his mother, but he hopes his three children can build different lives. In Mongolia, almost all herders’ children live far from their families, raised by grandparents or housed in school facilities in the so-called “sums” — small administrative centers that dot the steppe and gather scattered nomadic communities. Sums provide schools, dormitories and essential services, becoming the only point of reference for childhood, while parents remain on the steppe, isolated, tending their herds.

“In these years, thanks to the goats, we’ve managed to educate our children and improve our quality of life, but it’s a job destined to become unsustainable,” Batkhuu says.

In the past two decades, the global thirst for cashmere has surged and will keep growing: Valued at roughly $2.8 billion in 2023, it is projected to reach about $4.24 billion by 2030. The market is being carried by the wave of “fast luxury,” where fashion houses turn once-exclusive fabrics into accessible goods without shedding their premium label. Cashmere sweaters that once cost hundreds of dollars and were reserved for a wealthy few are now sold more widely, albeit often made from lower-quality yarn. This model leverages the branding of high-end materials while producing at mass-market volume and lower margins.

For Mongolian herders, this initially meant higher incomes — but only in the short term. Lured by seemingly easy profits, they became dependent on a commodity whose value is dictated by global demand and whose price is hard to predict. To survive seasons when cashmere prices drop and profit margins shrink, herders have been pushed to expand their goat herds. This growth, however, carries a heavy cost: intensified pressure on the land.

According to Mongolia’s Information and Research Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment, 76% of the nation’s pastures now show signs of desertification — the degradation of land from a fertile state to one where nothing grows — ranging from mild to very severe. The causes, researchers say, lie partly in climate change and drought, but also in human activity — above all, overgrazing.

Goats are not grass grazers by nature, like sheep or cattle: Put a sheep in a pasture for a week, and it will rotate its way around, nibbling the tops of leaves that will regrow in a few days. Goats naturally browse for leaves, seeds and plants that often grow higher off the ground, but if put in a grassland pasture, they will tear the grasses up from the root, stripping the land of its ability to renew itself and hastening the advance of desertification.

At the current pace of land degradation, herding may become untenable for the next generation. “Our pastures’ capacity is exceeded every year,” says Bat Oyun Tserenpurev, director of the institute’s agrometeorological research division. “In 2024, Mongolia could sustain a maximum of 110 million sheep equivalents, but the number of animals surpassed that threshold by almost 37 million.”

Pasture capacity is measured in “sheep equivalents”: one goat equals 0.9 sheep, one cow or horse equals six sheep and one camel equals seven sheep. In practice, Mongolia’s grasslands last year had to feed the equivalent of 147 million sheep — far more than the land can bear. Goats now make up nearly 40% of all livestock, and their rapid increase has been the main driver of this dramatic change in the landscape. “To slow desertification, we must cut numbers and bring them back in line with what the pastures can truly sustain,” Tserenpurev concludes.

The data reveals the scale of the crisis; on the ground, its effects are visible. Oyun Tsevelmaa, a small woman with a sharp gaze and wind-scarred face, has led the Shireet Khugjil cooperative in Undurshireet, 125 miles west of Ulaanbaatar, for years. She has watched the steppe grow poorer season after season.

“Twenty-five years ago, the grass reached my knees. Today, it barely covers my fingers,” she says. “We’ve lost biodiversity and many plants essential for our animals. Before 1990, Soviet cooperatives and herders jointly managed the pastures. Now everyone acts independently, and no one is held accountable for misuse.”

From the small cluster of houses that hosts her cooperative, Tsevelmaa drives along a dirt track across the plateau. The wind cuts through the open steppe, bending the last tufts of grass and exposing the dry earth. Herds move slowly, scraping at what remains of an exhausted landscape. In the distance stands a wire fence: Tsevelmaa built it in 2017 to protect a small plot from grazing. Inside, the grass grows several centimeters higher — a rare patch of green in a sea of brown. Part of a study by the Mongolian National Federation of Pasture User Groups, a network coordinating herders’ associations for sustainable pasture management, it offers visible proof of what happens when land is simply given time to rest. These modest experiments show that the steppe can still heal if the pressure eases. But instead of reducing herds, the market has offered a different answer: certifications.

Each year, the SFA certifies several thousand tons of Mongolian and Chinese cashmere bound for Europe, where brands market it as “sustainable” or “responsible.” The organization claims one of its primary certifications, the Animal Fibre Standard, “is the only cashmere standard that aims to improve goat welfare, safeguard biodiversity and land, promote decent work and enhance fibre quality through an effective management system and assured chain of custody.”

Materials provided to the organization’s 60-plus brand partners include example claims that brands can make, including “By sourcing cashmere that is ‘SFA Certified’, [company/brand] helps to ensure animal welfare and supports the SFA’s work in improving environmental practices and the livelihoods of herders,” and “In buying this garment you are contributing to the responsible sourcing of cashmere.”

But behind the polished branding lies a deeper question: How are terms like “sustainable” or “responsible” defined, and by whom? Experts and herders alike argue that SFA standards focus heavily on fiber quality and animal welfare, while criteria for biodiversity and land use are few and vague. There are some 97 points in their standards document on the care and keeping of animals, while there are only 21 for land management, and many of them are mere suggestions — herders “may take steps to restore degraded land,” for example — rather than actual commitments.

“These standards don’t really take soil health into account,” says Tungalag Ulambayar, an independent pastoralism expert and consultant for the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. “They claim to, but it’s almost impossible to accurately and continuously measure the well-being of the land.”

Doubts are reinforced by the very structure of the certification. The SFA Animal Fibre Standard used to certify their cashmere relies primarily on a bureaucratic process with little substantive oversight: Herders first conduct a self-assessment against the standard, then documents are reviewed by SFA staff or a designated committee and, finally, a third-party audit is carried out by approved auditors who verify compliance on-site. Critics argue that this model provides brands with a convenient ethical shield while their accountability remains minimal.

The SFA’s system largely responds to the demands of companies and customers. On the membership page, the benefits are clearly framed in terms of corporate advantage: “By becoming a member of the SFA, your company can gain valuable benefits that help protect your reputation and make credible claims” concerning “responsible sourcing” of cashmere, based on the protection of natural resources, animal welfare and working conditions for herders.

Guidelines intended to protect the land have had little impact on the ground. Stocking rates, the alliance’s guidelines note, “must be appropriate for the pasture … and take into account land type, pasture quality, seasonal conditions, class of stock, and available feed resources,” but no metrics — for example, the number of animals per hectare — are established.

In a country where pasture capacity has long been exceeded by almost 50%, these considerations have not prevented certification from being issued.

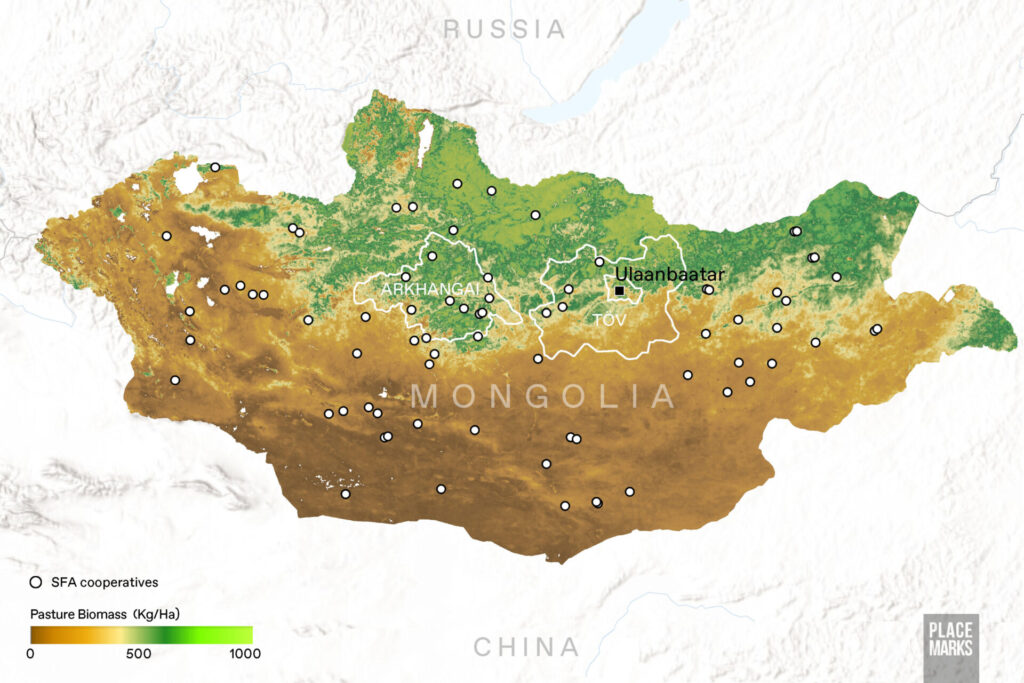

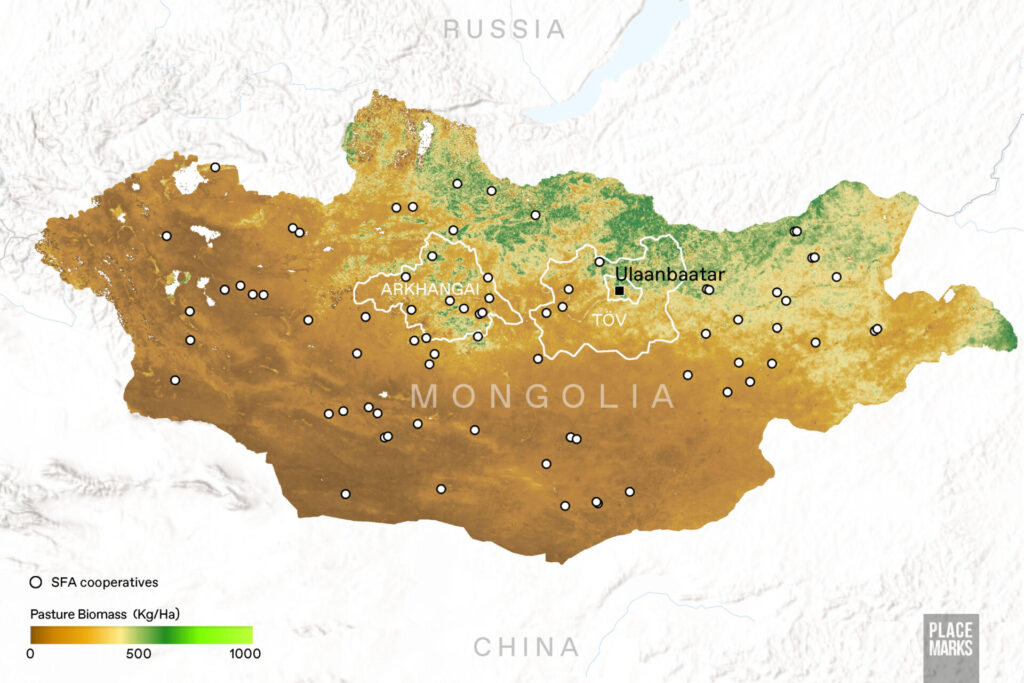

To test the SFA’s sustainability claims, New Lines superimposed the locations of certified cooperatives onto a map of Mongolia’s degraded pastures. The result is striking: Around 90% of certified co-ops operate in areas already heavily affected by desertification, including some that were recently awarded for their “sustainable” practices.

Each year, the SFA awards cash prizes to cooperatives and herders who “best align with SFA’s sustainability targets.” Among the six categories of awards, only one recognizes the best cooperative for land management. Several winners in other categories come from regions suffering severe land degradation.

The SFA didn’t respond directly to New Lines’ questions about desertification.

Even at the SFA, the question of what is “sustainable” has been murky. In 2020, the SFA’s former CEO, Charles Hubbard, gave a frank and detailed interview to the magazine Mongolian Economy, in which he discussed the factors that complicate cleaning up the cashmere supply chain. When asked about the certification process, he said, “At this moment we cannot say that this cashmere fiber is certified as sustainable. … We are often asked ‘Is SFA fiber certified sustainable?’ and the answer is no.” The SFA, he explained, simply registers herding communities that follow its code of practice, with the hope that “in the fullness of time, [this] may lead to the sustainable production of fiber.” (The SFA did not respond to our direct questions about whether or not they can now claim their cashmere is certified sustainable.) In practice, the system relies on self-assessments and limited monitoring — with no scientific measurement of soil or pasture health, which, Hubbard conceded, “would require years of research” to establish any meaningful baseline.

“The SFA is, in reality, an intermediary between brands and herders: It allows brands to display an ethical label on a supply chain that still operates according to the same economic logic,” says Ulambayar, the pastoralism expert for the United Nations.

Adding to the criticism, Burmaa Dashbal, a former representative of the Mongolian National Federation of Pasture User Groups, says the SFA built its system on the groundwork of others. “They took the standards we had developed,” she says. “We spent 15 years training and monitoring 50 cooperatives; they certified 200 in just a few years, simply asking herders if they wanted certification. And of course, everyone says: ‘Sure, I treat my goats well.’ It’s a quick, superficial system that doesn’t change practices on the ground.”

Ultimately, experts in ecology and pastoralism agree that the SFA borrows the language of sustainability while leaving its substance untouched. From afar, the system appears responsible and transparent — but up close, it remains driven by the same market forces that helped create Mongolia’s cashmere crisis in the first place.

While herders see little tangible benefit on the ground, cooperatives continue to join the alliance, drawn by the hope of higher incomes. Currently, around 70 Mongolian cooperatives hold a valid SFA certification. Renewed annually, the process involves training sessions, internal self-assessments and independent audits conducted by firms based in Ulaanbaatar or Paris.

The SFA standards are primarily tailored to meet the demands of its corporate members rather than the needs of Mongolian herders. Training, for example, according to the herders New Lines spoke to, focuses on combing goats in cleaner environments to avoid residues in the fiber, sorting cashmere by color or selectively breeding goats for lighter shades. While these practices intensify the herders’ workload, the financial rewards the SFA touts to the herders it certifies — among them “Increased value through SFA Animal Fibre Standards and Chain of Custody” as well as “Opportunities to negotiate a higher fibre price” — often fail to materialize.

Vandandorj Sumiya, the SFA’s national director in Mongolia, defends the alliance’s work. “Benefits for cooperatives can take different forms — veterinary services, hay or vaccine supplies and, above all, a better position on the market. Today, companies want to buy certified cashmere, and that increases cooperatives’ competitiveness.”

“We do not force anyone,” Sumiya explains. “It’s a voluntary standard. Usually, companies or brands tell us which cooperatives they work with and ask us to certify them.”

From the steppe, cashmere travels toward Ulaanbaatar, where the long process of transformation begins: sorting by color, washing and mechanical combing — dehairing — to separate the fine undercoat from the coarser hairs. The fiber is then inspected again, dyed, spun and prepared for export, stacked in containers bound for Europe, China and Russia.

The city’s cashmere factories operate in the industrial outskirts of Ulaanbaatar — home to nearly half of Mongolia’s population, including thousands of former herders who left the steppe after losing their income.

Inside the warehouse of Khanbogd, one of Mongolia’s largest fiber washing and dehairing facilities, workers haul massive white sacks filled with raw fiber from every corner of the country. “About 50% of the cashmere comes from SFA-certified cooperatives, and the other half from intermediaries who collect fiber from herders and mix it,” one of the plant’s managers tells New Lines, admitting that transparency remains elusive. “In the end, it’s impossible to know what arrives, and from where.”

Founded in the early 2000s, Khanbogd says it supplies some of the most prestigious European luxury houses and is a member of the Sustainable Fibre Alliance.

Seated in her office, surrounded by spools of yarn and fabric samples, Gantsetseg Choidon, Khanbogd’s CEO and owner, describes how the cashmere supply chain moves once it hits her factory.

“Between 50 and 60% of our cashmere ends up in Italy,” she says. Several luxury designers source directly from the factory. “But the price difference between certified and uncertified cashmere is minimal — European brands that buy SFA-certified cashmere pay only about $3 more per pound than for noncertified fiber, and this year even less.”

In 2024, Khanbogd sold certified fiber at $190 per pound, while some competitors — including Chinese suppliers — sold at $200 for uncertified batches. “We ask brands to pay more for certified cashmere,” Choidon continues, “but the answer is always the same: They tell me that they are following the market rate.”

The imbalance is stark. “European brands set the prices and payment terms,” she says. “We have to cover warehouse costs in Italy, plus insurance and shipping. And we only get paid 45 days after delivery. They talk about sustainability, but the truth is they’re crushing us economically.”

Despite positioning SFA membership to herders as a way to negotiate higher fiber prices, the SFA told New Lines in a statement that it “does not set prices, and market premiums are inconsistent across suppliers and seasons. … Certification can, however, create wider value through improved access to buyers, greater bargaining power, participation in transparent supply chains, and access to lower-cost Green Finance that reduces dependency on high-interest informal loans.”

In the factory, the sound of the machines blends with the soft rustle of fiber slipping through workers’ hands. “We must support the herders,” Choidon says quietly. “They’re slowly disappearing. If they can no longer make a living, they’ll vanish — and with them, Mongolian cashmere will disappear too.”

For herders, “sustainability” now means something far more prosaic: economic survival. The international system that promises to make cashmere “ethical” has instead added new layers of bureaucracy and expectation, without offering a way to reduce herd numbers or secure stable incomes.

Paradoxically, while herders face mounting hardship and the risk of disappearing altogether, cooperatives are multiplying. Many have been created not through grassroots organization, but to satisfy brand requirements for traceability. “In 2022 and 2023, many cooperatives were formed because international clients and brands wanted to trace the supply chain and have standards,” explains Javkhlanbayar Tserendash, president of the Tsagaan Tekhiin Uguuj cooperative in Bayankhongor province, at the edge of the Gobi desert.

Founded in 2023, his cooperative now counts 700 members and collects cashmere from more than 4,000 herders, producing 400 to 500 tons of fiber annually. The business once belonged to his father, who worked as an intermediary between herders and factories. Today, it has been restructured — at least formally — to become one of Mongolia’s top five cooperatives and a direct supplier to major brands.

“It’s hard to say who doesn’t buy from us,” Tserendash admits. Along with Khanbogd and other Mongolian buyers like Sor and Goyol, he says the cooperative works with international brands like Hermes. “They tell us the volume, and we deliver the quantity.”

Tserendash says certification mainly serves European markets, where sustainability has become a commercial necessity. “Clients want guarantees on traceability and quality,” he says, “but the price is set by the global market. Europe and China determine the value of cashmere, not us. Even if Mongolia declares an official price, it always adjusts to international quotations, with added washing and dehairing costs.”

The result, he concedes, is that herders’ profits remain minimal. “It’s not easy to predict market trends. We represent hundreds of herders and must calculate risks, trying to sell at the best possible price. But sustainability, as it’s defined today, depends on who’s looking at it.”

While Khanbogd’s director and the head of the top cooperative lament the power of European brands, those further down the chain feel the same frustration toward the factories. Oyun, the herder who became director of the Shireet Khugjil cooperative, recounts her latest negotiations. “We argued for a long time with Khanbogd over the price,” she says. “Every year, we produce between 10 and 12 tons of cashmere. In 2024 we sold at 360,000 tugrik [about $100] per pound; this year, the highest price was 330,000.” The decline is painful, especially since the costs of feed and transport continue to climb.

Herders sell to cooperatives, cooperatives to factories, factories to brands. At every step, value consolidates upward. Those at the base of the chain — the herders whose labor and land sustain it all — remain the most exposed to market shocks.

For wealthy consumers, an SFA-certified cashmere sweater offers warmth and the comfort of a “conscious” choice — a luxury softened by the promise of sustainability. But for the herders, the label means little more than extra paperwork and unfulfilled promises.

“I think pasture management is a myth,” Oyun says bitterly. “If a herder reduces their livestock, their income drops. No one buys our raw material because it’s sustainable. There’s no policy that truly encourages herders to take care of the soil.”

In recent years, Mongolia has suffered a series of brutal winters followed by parched summers that have decimated herds and shrunk pastures. For herders, this means more insecurity, lower incomes and deeper debt.

As the sun dips behind the mountains, Oyun watches her goats return to camp. Around her, the steppe stretches bare and silent — fragile, exhausted, waiting for a time to heal. “We’re asking that factories recognize us with a share of the profits when they sell the cashmere in Europe,” she says quietly. “We’d like to benefit from these luxury goods too.”

All photographs by Daniela Sala.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.