Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, it has recommitted itself to a degree of domestic political repression and international isolation not seen since the Soviet era. Many Russians want out.

In an echo of the major emigrations of the Soviet era — the first of which followed the Russian Revolution and Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917, with others following immediately after World War II and in the 1970s — close to a million Russians have fled since 2022. Some of them left following the initial invasion, others in response to Russia’s “mobilization” of 300,000 men last fall. (This year’s mutiny by Russia’s Wagner paramilitaries, which exposed cracks in the Putin regime, also caused a run on plane tickets.)

Reasons for leaving include (for men) the ongoing prospect of being sent to war. In July, President Vladimir Putin passed a law raising the maximum conscription age to 30, which could mean hundreds of thousands more are forced to fight. More broadly, the domestic repression that had escalated gradually throughout the Putin era, but which it was possible for the “apolitical” to ignore, is now pervasive. Wartime censorship has led to the closing of independent media and the arrest of thousands of dissenters. A new wave of “patriotic” education requires schoolchildren to support the war. Russia’s main opposition leaders, the politician and anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny and the journalist and human rights activist Vladimir Kara-Murza, a dual Russian-British national, have been sentenced to decades in prison.

What is largely absent from the Kremlin’s messaging is ideas. The Soviet Union had Marxism-Leninism, and Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev once even promised the utopia of full communism by 1980, yet Putin offers only an inchoate, resentful, armed nostalgia that harks back at times to the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany in 1945, and at others to a vision of restored imperial “greatness” guided by Russian Orthodoxy.

Many of Russia’s most engaged citizens — among them the political thinkers, artists and academics best equipped to analyze, criticize and hold up a mirror to the dictatorship — can now see their country only from the outside and don’t know when, or if, they will be ever able to return. They are not only experiencing a profound sense of shock and dislocation but also endeavoring to sustain the life of ideas that the Kremlin has suppressed within Russia itself.

Victoria Lomasko is an artist best known in the West for her acclaimed 2017 book “Other Russias,” a work of illustrated reportage that conveyed the corrupt atmosphere of the Putin era through depictions of lesser-known areas of Russian life such as youth prisons and modern slavery, as well as the (much higher-profile) Pussy Riot trial of 2012, in which members of the feminist punk collective were charged with “premeditated hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” for staging a protest-performance in Moscow’s largest cathedral. Her 2023 book, “The Last Soviet Artist,” is about the legacies of the Soviet empire and the conflict between generations.

“This war wasn’t possible without the dictatorship,” Lomasko tells New Lines. As soon as Putin launched the invasion, she knew that whatever freedom of expression Russian artists still enjoyed was about to end. She left on March 5, 2022, convinced that, based on her reputation as an opposition artist, her apartment would be raided and her work destroyed. She went first to Belgium via Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and France, and then moved temporarily to Leipzig, Germany, supported by a Martin Roth Initiative fellowship for artists at risk. She has since moved to Berlin.

Having documented changes in Russian society over 13 years, she says, “I really predicted this war in my works.” Stuck in Russia during the pandemic, she saw it foretold in Moscow’s urban landscape as she wandered the capital. “I was frightened by the number of posters I saw reminding everyone that we had been the victors in World War II,” she says. “On the subway I occasionally ended up on the so-called Victory Train, which was decorated with photos of Soviet soldiers holding automatic rifles and anti-fascist posters.” Similar images were visible on the streets and on TV.

In Russia, World War II is a vexed subject. The Soviet Union suffered greater losses than any other country; an estimated 27 million, military and civilian, died. Many Russians feel, with some justification, that their sacrifices and contribution to Hitler’s defeat were later minimized in the West because of the Cold War. However, successive generations in Russia have consumed heroic myths about the war and have little knowledge of such ignoble episodes as the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 or Soviet acts of aggression, such as the invasions of Poland and Finland in 1939 and the Baltic countries in 1940. In Russia’s popular imagination, the war began when Germany invaded the USSR in 1941.

Most ominous of all, Lomasko says, was a trip she took to the Main Cathedral of the Armed Forces, a dark green, onion-domed monument to Russian Orthodox nationalism and military prowess that was consecrated on the outskirts of Moscow in June 2020. She says it appears to have been built “to celebrate a future victory over Ukraine and the West.” In her writings, she has described it as “demonic” and resembling “a horror movie castle.”

The cathedral harks back symbolically to the Russian Orthodox Church’s patriotic role in the defense against Nazi Germany. Implicitly, it also refers to the accommodation Stalin imposed on the church in 1943 whereby, in an ostensible reversal of the anti-religious campaigns of the Russian Revolution, it was encouraged to open churches and train new priests in exchange for galvanizing the war effort.

Photographs Lomasko showed New Lines of the cathedral’s interior reveal history-themed martial paintings with holy trimmings, presided over by a looming golden Christ. (An early incarnation of the cathedral contained a mosaic depicting Putin, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, though this was reportedly vetoed at a late stage by the Kremlin).

“Each ordinary step [was] an adventure,” Lomasko says of her first year and a half in exile. Her Russian bank card didn’t work when she arrived, and once she had settled in Leipzig — part of the eastern German state of Saxony, which, as a stronghold of the AfD, or Alternative for Germany party, is known for its anti-immigrant politics — she found that, despite having received a one-year fellowship, she faced ongoing visa hassles. “I believe that there must be an official solution [for] Russian dissidents who cannot return home,” she says.

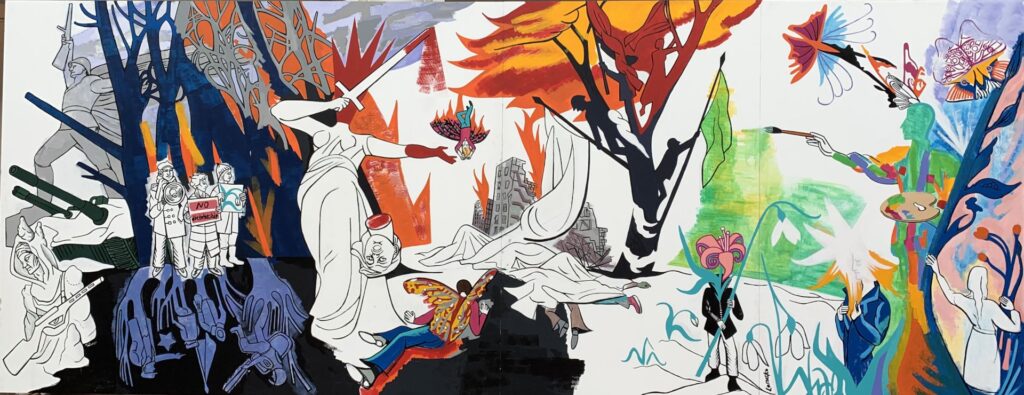

After setting up her studio in Leipzig, she moved on from graphic reportage and analyzing Kremlin propaganda because, she says, “The most dark things have already happened.” Now she describes herself only as an artist and sets out visual metaphors on large painted panels. As she explains in a recent artist’s statement: “If I were in Ukraine, I would depict the day-to-day life of its residents, living in besieged cities, but I’m not there. … I am not a witness of war; I am a witness of the dictatorship that lies at the root of the tragedy.”

Her new works respond to the war as what she has called “the suicide of post-Soviet reality,” which she defines as the phenomenon of old people in power wanting to turn back history. “They will be destroyed with their plans and dreams about the Soviet past,” she says.

And whereas the Kremlin seeks to mythologize Soviet military history, her works seek to tie it to the present. In her 3-by-8-meter mural “The Changing of the Seasons,” the central image is of the 279-foot “Motherland Calls” statue of Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad) beheading itself with a sword. As the viewer’s eye moves from left to right, the panel ends with a young woman “turning the page” on the image, opening an Edenic space of nature and renewal.

Her painting “Shame” includes a reworking of the Soviet War Memorial in Berlin, which was well known to Soviet-era Russians from its depiction on the 1-ruble coin. The original features a Soviet soldier standing above a broken swastika, holding a sword in one hand and cradling a child in the other. In her version, the soldier now cradles the letter “Z,” a symbol of Russia’s aggression, striped in the orange and black of the Ribbon of St. George associated with Russian military decorations. The child lies broken on the ground, wounded by the soldier’s sword.

Lomasko has moved to a Berlin that now seems the polar opposite of the Nazi stronghold of Soviet war films; the liberal city-state has offered her a three-year visa. From there, she can begin to envision a better future for Russia, though as yet a low-resolution one: “I feel that a new Russia will be an interesting place, a place of experiments and art,” she says.

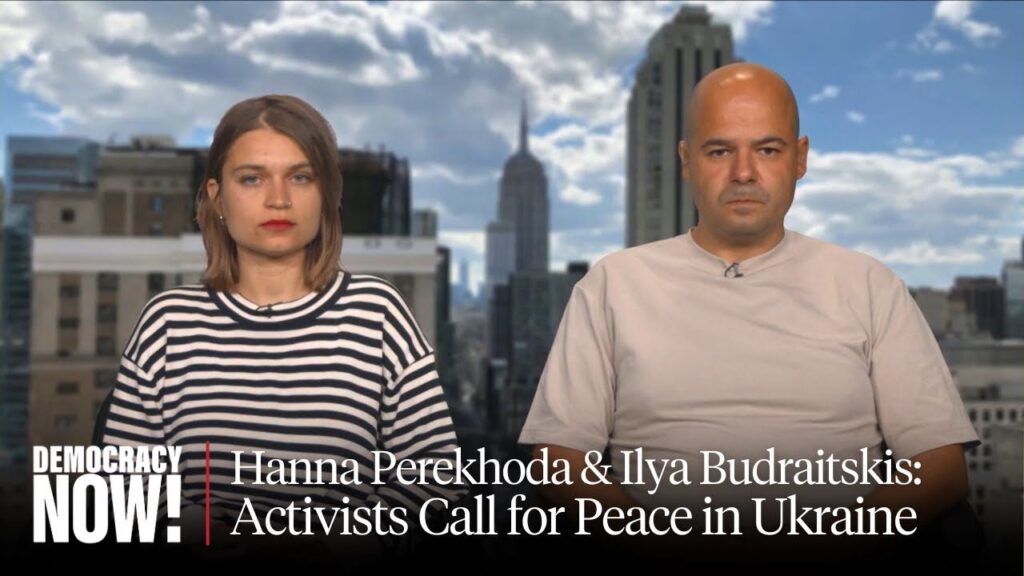

Ilya Budraitskis has made the future his project. A political and cultural theorist who taught at the Moscow School for Social and Economic Sciences, he left Russia in March 2022 via Istanbul, and is now a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of “Dissidents among Dissidents: Ideology, Politics and the Left in Post-Soviet Russia” (2022) and a co-founder of Posle (“After”), a network of Russian leftist intellectuals who oppose the war in Ukraine, which, according to its mission statement, “sets out to examine the structure of these problems and imagine the way out.” Posle’s website publishes in both Russian and English.

Budraitskis has given Putin’s bloody vision a familiar name: fascism. His designation is not casually given, but carefully theorized. In his October 2022 essay, “Putinism: A New Form of Fascism?” published in the Marxist journal Spectre, he argued that what has made Putin’s Russia fascist since Feb. 24, 2022, is that it criminalizes all dissent, combines an atmosphere of fear and chauvinism with aggression abroad and identifies the will of the nation with the decisions of its authoritarian leader. Putin’s form of fascism, he wrote, fuses the country’s long history of imperialism with elements of gangster capitalism and Trump-and-Orban-style Western right-wing populism (which he does not characterize as fully fascist).

Part of the impetus behind Putin’s imperialism in Ukraine, he tells New Lines, is rooted in the Soviet 1970s. “People in the KGB and at the top of the Party saw that official Marxism was not functioning well,” he says. “That was when Putin was part of this apparatus.”

That decline of Soviet-era official Marxism-Leninism was perhaps most memorably articulated by an exiled Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his 1975 “Warning to the West”: “In the Soviet Union today, Marxism has fallen so low that it has become an anecdote, it’s simply an object of contempt. No serious person in our country today, not even university and high school students, can talk about Marxism without smiling, without laughing.”

Within the KGB, Budraitskis says, there was a search for new ideas. “They experimented with Russian nationalism,” he says, and by the late 1970s and early 1980s, KGB schools were exploring notions of a Russian Orthodox empire. But, he adds: “The restoration of historical Russia is not just Putin’s idea. It’s the collective tradition of the state apparatus in Russia, rooted in the secret service, in the army. The principle is that the power of the tsar is God-given, and that the empire should expand because it is a sacred, religious duty.”

The question of Russian imperialism, Budraitskis says, is bound up with Putin’s view of the former USSR. “When Putin declares that Lenin created Ukraine, he is right in some sense, because without Lenin there would be no Ukraine within such borders.” What Putin called “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century” — the dissolution of the USSR — was possible only because the right to exit the union was established in the Soviet Constitution. By Putin’s logic, Budraitskis says, the creation of the Soviet Union was also a “geopolitical catastrophe” because it established grounds for the self-determination of the Soviet republics.

Putin, though nostalgic for the Soviet Union, its dictatorial powers and its security services, frequently criticizes its revolutionary founders. Following the mutiny by Wagner paramilitaries on June 23, for example, Putin — in an unmistakable reference to the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power — said: “It’s a stab in the back of our country and our people. Exactly this blow was dealt in 1917 when the country was in World War I but its victory was stolen.”

Posle’s mission, Budraitskis says, comes in two parts. “For the Russian-speaking audience, we want to develop a left-socialist anti-war perspective, and to develop the political language of the Russian left towards this war.”

He divides the Russian left into two groups: pro-war and anti-war. “The pro-war camp consists of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and some groups around it that came from the Stalinist tradition,” he says. The Communist Party is an official, parliamentary party in Russia that routinely defers to Putin on major policy issues. “For them, the restoration of the Soviet Union is the core of their program. Theirs is a clearly imperialistic and anti-democratic way.” But there is also an anti-Stalinist, anti-authoritarian wing. “The anti-war left is represented by various socialists and anarchists who have continued to exist, but without the ability to hold any public events inside the country. Many of them have left, been imprisoned, or continue underground,” Budraitskis says.

In addition to providing intellectual support for Russia’s anti-war left, he says, Posle’s second mission is to engage in critical dialogue with the English-speaking left. “Among the Western left, we see a deep misunderstanding of what is going on in Ukraine,” he says. “We see how many Western leftists just repeat narratives of Putinist propaganda.”

In Putin’s worldview, he says, “There is no such subject or factor as the people of Ukraine. His view is that they belong to a culture, a civilization, that has some kind of essence, and that Ukrainians are Russians despite their own beliefs about themselves.” This view, he says, is mirrored by those Western leftists who ignore the agency of Ukrainians. “This comes from an unconscious imperialist view, that the global situation can be explained from London, from New York, from Berlin, but not from Kyiv, that’s for sure.”

The tendency to view the world as “a big chess game,” as Budraitskis puts it, also leads to superficial thinking about NATO’s influence in Eastern Europe. While he acknowledges concerns about military budgets and NATO expansion, he says, “The populations of Poland and the Baltic states believed it was good to be in NATO. Their pro-NATO orientation was not just the result of pressure from the West, but of their own historical experience.” This, he says, was ignored by both Russia and the Western left. “It’s clear that the Baltic states only exist now because of NATO,” he says. “It’s a pure fact. They have been defined in [Russian] state discourse as ‘Russophobic,’[so] their sovereignty could be called into question.”

Posle, he emphasizes, is a modest outfit that depends on donations, and most of its contributors don’t get paid. He doubts he’s influenced the conversation in the West much, but says, “It definitely helps to give more arguments to those from the Western left who supported the right of Ukraine to resist. If we look at the arguments of [those on] the left who deny the agency of Ukraine, we see how easily they move toward conspiracy theories and buy the narratives of Russian propaganda, how they break with the foundations of Marxist, materialist analysis of the situation.” This element of the Western left, he says, “follows the right-wing agenda.”

In early 2022, after the full-scale invasion began, many in the West asked why so few Russians appeared to be protesting. Pavel Otdelnov, an internationally exhibited painter, was one of those who did. On March 4 last year, he staged a one-person demonstration outside a supermarket in Kolomenskoye, a southern part of Moscow where he knew there would be fewer police than in the center. He held up a sign that read, “Eto beZumiye” (“This is madness”). He had replaced the Cyrillic “z” with an enlarged Latin one, by then already synonymous with Putin’s aggression.

It was not the first time he had addressed the war. Back in 2015, when it had still been possible to satirize Kremlin policy in a major gallery, he had put on an art installation at the Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art that responded to the 2014 annexation of Crimea. Titled “Unheimlich,” which literally means both “un-home-like” and “unconcealed” in German and is generally translated into English as “uncanny,” the show was based on Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay of the same title. The idea, Otdelnov says, was to show how “the war had been inside ordinary things all these years.” In the exhibition, an ornamental wall carpet — a common feature of Russian homes — had tiny soldiers nestled within its designs, while a toy tank crept out from behind an armchair.

Freudian psychology is one of many Western intellectual trends that was suppressed in the Soviet Union. Otdelnov became acquainted with Freud’s work through lectures in the history of ideas at Moscow’s Institute of Contemporary Art, where it was understood that Freudian psychoanalysis underpinned swathes of 20th-century Western thought. While he doesn’t think Freud’s ideas offer any solutions for the current crisis, he says, “In ‘Unheimlich,’ I remembered Freud because he introduced a paradoxical concept: The paradox of the familiar and the cozy turning into horror is one of Freud’s most vivid and accurate intuitions.”

To protest the “madness” of a war outside a supermarket referred, arguably, to the same paradox. His protest provoked a few reactions. Some people approached and said they would like to speak out, too. One man argued, “We are defending the LDNR because they asked us to!” — a reference to the Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics,” parts of Ukraine whose “independence” Putin had just recognized. Another recalled a small demonstration in Red Square in 1968 against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia: “There were eight of them, but they were the best people!” Another foretold “a long, hard break with the whole world.”

But mostly, Otdelnov says, people didn’t care about his protest. “For me it was the only action that could give me back a sense of reality and help me to overcome the fear. It was so unbearable to feel powerless to change something.” While his individual protest was still technically legal, Russia was, that very day, to undergo a legal and epistemic earthquake as the government rushed through two new laws against “disseminating false information” and “discrediting the Russian armed forces” that effectively outlawed protesting the invasion or revealing unpalatable facts about it.

Free speech had been in steep decline in Russia for the previous decade. Otdelnov points to the 2012 Pussy Riot trial, based on a law against hurting the feelings of religious believers, as a milestone in that decline. The “foreign agent” law of the same year, which put onerous and ever-increasing demands on anyone receiving financial support from abroad, was another. Then, after 2014, a series of legislative amendments made it increasingly difficult to organize meaningful large-scale demonstrations. The closure in 2021 of Memorial, a human rights organization established during the era of glasnost to document the history of political repression in the USSR — and in particular during Stalin’s terror of the 1930s — was another bad sign.

So, a week after the invasion, Otdelnov decided to leave. He went temporarily to Sweden, where he had recently held an exhibition. With another show lined up in London, he successfully applied for a U.K. Global Talent visa for people in the arts and moved his family over.

His London show, “Acting Out” was held at Pushkin House, an independent Russian cultural center that had expressed its support for Ukraine as soon as the war broke out. Composed of a series of potent visual metaphors about post-Soviet Russia and billed as “critical commentary on the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe associated with the war in Ukraine,” the show could not have been more timely.

One room of paintings, located suggestively in the building’s basement, was arranged around the theme of ressentiment, a concept most frequently associated with Friedrich Nietzsche, another thinker whose work was suppressed in the USSR. It linked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to what Otdelnov terms “a collective historical resentment for the defeat in the Cold War and for the collapse of the USSR.” One memorable piece, titled “Money” depicted the vast quantities of obsolete ruble banknotes that had been stuffed into nuclear missile silos following the hyperinflation of the 1990s, thereby capturing the combustible sense of bygone Soviet power and post-Soviet grievance that Putin has appealed to — and perhaps even temporarily assuaged — with his aggressive foreign policy.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, his painting “The Path” shows a red carpet disappearing into a snowy landscape, a reference to his sense of futurelessness in Putin’s Russia. Much as Stalin’s adopted revolutionary name referred to “stal’” (steel), making him a “man of steel,” Putin’s (real) family name contains the word “put’” (path). The meaning, Otdelnov says, is obvious to Russians, “He knows the way and leads.”

The notion of Putin leading Russians on a path to nowhere dovetails with Otdelnov’s current psychological fascination, conformism. The problems of dictatorship, he suggests, are illuminated by sociological studies conducted following World War II. He cites the Polish-American psychologist Solomon Asch’s experiments, carried out in Swarthmore College from 1951, as having “proved that conformity is one of the main features of human nature.” He also refers to the psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford Prison experiment, which studied situational variables in the behavior of participants assigned the roles of prisoners and guards. “I know that modern scientists have questions about the approach of that experiment,” he says. “However, these experiments convincingly demonstrate how efficient simple methods of manipulation are.”

Otdelnov, reluctant to turn his back on long-standing relationships, has stayed in touch via the Russian social media platform VKontakte with some people who support or don’t oppose the war, and has been able to sample the ways in which they have rationalized the invasion.

He finds the foundations of these rationalizations in what he calls “the state idea” as it was promoted in Soviet education and the Young Pioneers communist youth organization. “The oath that each pioneer took was ‘to live and fight as the Communist Party of the USSR teaches,’ and the main slogan was ‘Always ready!’ To die for the state has always been the highest honor, the highest destiny of the Soviet people,” according to Soviet ideology. This message, he says, was extensively reiterated in Soviet-era war and espionage films.

But he also cautions that the current style of state propaganda is different, in that it depends on doubt rather than slogans. “‘We do not know the whole truth’ is perhaps the main result of this machine,” he says. “Modern Russian propaganda generates many versions of the same events.”

In one version, one of his correspondents described the war as a “tragedy,” but also a matter of zero-sum geopolitics in which the blood was on the hands of those U.S. and EU politicians who “handed out cookies on the Maidan,” meaning that they encouraged the Ukrainian uprising against the Russian-backed government of President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. In another, the war with Ukraine was a necessary preemptive strike by Russia, since NATO was a threat, and the Soviet Union had suffered in 1941 because it had failed to attack Nazi Germany first. In yet another, doubt was cast on news of Russian atrocities, such as the March 2022 Bucha massacre, which was said to have been orchestrated by Ukrainian intelligence, its location chosen strategically to resonate with the English word “butcher.”

Other correspondents seized upon the language of outrage that has emerged in Ukraine following Russian attacks. “After each missile attack, [some Ukrainians] write ‘you are not people.’ They call the Russians ‘orcs,’ which is emotionally completely understandable,” Otdelnov says. “However, it is precisely this narrative that the state propaganda emphasizes: ‘They do not consider us to be human beings.’”

Then there are the references to what might be termed “smoking gun” texts, supposed to be at the heart of Western foreign policy. One is the Polish-American political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1997 geopolitics tract “The Grand Chessboard,” which, Otdelnov says, “was probably read by every Russian who was more or less interested in politics.” In a 1997 review in Foreign Affairs, David C. Hendrickson wrote that, “The heart of the book is the ambitious strategy it prescribes for extending the Euro-Atlantic community eastward to Ukraine and lending vigorous support to the newly independent republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus, part and parcel of what might be termed a strategy of ‘tough love’ for the Russians.”

Behind such references by Russians, Otdelnov says, there lies the idea that “the West has always hated Russia” and that “the collapse of the USSR and everything that led to it was initiated from outside.” This view, he says, is often predicated on a version of a popular, oft-cited conspiracy theory, known as “Dulles’ Plan,” which claims that Allen Dulles, head of the CIA from 1953 to 1961, plotted to destroy the USSR by attacking the cultural values of Soviet society with the help of internal accomplices.

Now, Otdelnov says, “The popular narrative is that Western countries dream of dividing Russia into many parts. The basis for the popularity of these ideas was the Soviet rhetoric of the Cold War and a simple psychological trap: It is easier for a person to believe that someone else is to blame for his troubles.”

Russia, he says, “must learn from the experience of recent years and firmly take the path of democracy.” That means openness and cooperation, respecting the rights of minorities, respecting civil rights and knowing how to defend them.

“It is quite difficult to talk about this now, since Russia is moving in the opposite direction,” Otdelnov says. “I communicate with those with whom I can speak. But it’s impossible to speak with people who speak only in propaganda cliches.” Since last year, he has lowered his expectations. “I’m thankful even if a person doesn’t post ‘Z’ and doesn’t justify crimes,” he says.

Andrei Zorin is a professor of Russian literature and history at the University of Oxford and the acclaimed biographer of Russia’s most famous pacifist, Leo Tolstoy. He moved to Oxford in 2004, and for nearly two decades was used to being able to return to Russia at will. He kept an apartment in Moscow and traveled back and forth four times a year, pursuing his research interests. But since Russia’s full-scale invasion he has felt like an emigre. “My status changed without me changing my physical location,” he tells New Lines.

Now he finds himself observing and participating in the debates among recent exiles about the nature of the current crisis. One argument, he says, can be paraphrased as, “Something went wrong and we have this horrible regime running the country.” The objective is then to find out what went wrong. Another holds that, “This regime is just a natural representation of the country as it is.” If that is true, he says, there is the additional question of whether Russia can ever change. “[One group] claims to believe — I am not sure they completely believe it — that it is hopeless, that it is ingrained in a thousand years’ history” he says. “The idea is that Putin is not a decisive factor.”

“This view,” Zorin points out, “has huge support from the other side of the front line. A lot of Ukrainians believe that they are not dealing with a regime, but with a country that is an aggressor by nature.” This manifests in Ukrainian descriptions of Russian forces as “orcs” — evil, nonhuman warriors from J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy world, Middle Earth. “I understand how people living in Ukraine could see it this way,” he says.

Another debate concerns low trust in the diaspora, which tends to discourage effective organization. “Many Russians, especially in emigration, where they can speak more freely, keep accusing each other of being connected with the FSB,” Zorin says, referring to Russia’s Federal Security Service, the successor to the KGB. Until the opposition leader Alexei Navalny was poisoned on a flight from Tomsk to Moscow in August 2020, he says, many Russians accused him of being backed by the Kremlin. “It was entirely idiotic, but it didn’t stop it from being widespread.”

Then there is the recurrent question of the power of propaganda. “You have to deal with the significant support within Russia for the war,” Zorin says. When the invasion began, he thought most of the bluster from the Russian public was “sofa militarism” that would not outlast real sacrifice and death. But it has. Now he hears Russians making rationalizations like “Maybe we shouldn’t have started it, but if we did, we should go on and win [since] there is no way back.”

But Zorin is not one of those exiles who thinks Russia should be abandoned to its militaristic fate or that espionage should prevent organization. Russia’s dire domestic scene, and the exodus it has created, has resulted in substantial brain drain and with it, opportunities to reorganize Russian intellectual life abroad. “If there will be a new Russia, they will need European-educated people to work there,” Zorin says.

Zorin is now involved in what he calls an “enormously exciting project” in Montenegro: the Faculty for Liberal Arts and Sciences (FLAS), a collaboration with professors from the Moscow School for Social and Economic Sciences, which is known as the Shaninka for its storied founder, the sociologist Teodor Shanin, who was born in the Jewish community of Polish Vilnius in 1930, spent time in forced exile in Siberia with his mother during World War II, and later began studying sociology in Jerusalem before continuing his academic career in Britain. The political scientist Ekaterina Shulman, sociologist Victor Vakhshtayn and linguist Marina Kalashnikova are among the academics involved in FLAS.

After the invasion, Zorin says, Russia forbade liberal arts education, probably because it has the word “liberal” in it (notwithstanding the absence of a historical connection between “liberal arts” and political liberalism). The liberal arts are broadly defined by an interdisciplinary approach to education, which contrasts sharply with the Soviet approach involving early vocational specialization.

Ljubomir Filipovic, a Montenegrin political scientist, is in the early stages of getting the institution officially accredited. Beginning with a $100,000 grant from the U.S. Russia Foundation, a U.S.-funded pro-democracy organization, FLAS plans to start an international university, initially drawing most of its students from among Russian-speakers and most of its teaching staff from Russian liberal arts programs that have been shut down by the Russian government.

It will begin with around 100 students, studying in half a dozen classrooms, with the star academics lecturing part time. Students will receive a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts and sciences, a qualification he says has already been confirmed by the Ministry of Education of Montenegro. Teaching will be mainly in English, but the institution will also partner with universities in the West to offer courses in Russian and Ukrainian.

FLAS will, ultimately, be a forum for ideas in exile. Filipovic’s colleague Andrey Fetisov, a co-founder and director of FLAS, is the former director of the School of Media and Communications at RANEPA, the Russian Presidential Academy of Economy and Public Administration in Moscow, and, since 2020, a collaborator with the Shaninka, where he and his colleagues had been developing a media faculty when the war began.

He left two months after the invasion, in part because of his opposition to the war, and in part because of the erosion of academic freedoms and the crackdown on liberal arts education in Russia. FLAS grew out of a meeting with Russian colleagues who came to visit him in Montenegro. Fetisov shared a document with New Lines outlining the project’s goals in relation to two imagined “extreme poles” of possibility for Russia’s future.

One, which presumes a fortuitous form of regime change in Russia, would be to “preserve Russian culture and train the next generation of political scientists, sociologists, lawyers and managers to work for a new modernisation of the state and society in Russia.” In the other, more catastrophic scenario, the war “destroys the state and society in the Russian Federation” and leads to a multigenerational crisis. In this case, the mission of FLAS would be “preserving the language and culture of historical Russia” and helping Russian emigres to adapt to the global labor market.

Regardless of what happens in Russia (there are, he acknowledges, “intermediate points of view”), he argues the achievements of Russia’s post-Soviet intellectuals should be acknowledged. “The new Russian diaspora has [the] unique experience of adapting Western social and cultural institutions in a post-totalitarian country and orienting towards European values,” he writes. “Among the important ideas that have been introduced into Russia’s intellectual class over the past 30 years are republicanism, human rights, rule of law, the separation of powers [and] freedom of speech.”

The failure of Russia’s intellectuals to gain traction for those ideas among the broad Russian public is, alas, only too obvious. Fetisov attributes what he calls “the failure of Russia’s modernization in the last 30-40 years” to — among other things — a lack of reflection about the Soviet period, a failure to coordinate economic and political reforms, and failure to develop a “non-Soviet, non-militarist, non-gulag” language of politics and public administration. That, in turn, was rooted in cultural factors: the conservatism of a large part of the Russian population, combined with the duration of their exposure to Soviet ideology.

By leaving Russia in the wake of Putin’s invasion, Fetisov says, Russia’s intellectuals have denied Putin’s regime a future. And the future, he says, is the business of FLAS. “Our students will be living and acting 20-30 years from now. We have tried and will continue to try to ensure that [they] overcome the dark legacy of Soviet totalitarianism.” Russia’s intellectual exodus is also, in a sense, an act of solidarity with the other countries of the former USSR. “The refusal to work on the image of the future for the aggressor government is work in the interests of the future development of Ukraine and other countries around the Russian Federation.”

While Soviet communism collapsed in 1991, certain habits of mind endured in Russia: the notion that Russia would always be besieged from abroad, that meaning had to be found in continued enmity with the West, and that, if Western countries could not themselves be defeated, a brutal example could at least be made of any country on Russia’s borders that dared to embrace ideas that had not first been mediated through Moscow. The result is that Moscow will be the source of fewer ideas than ever before.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.