Listen to this story

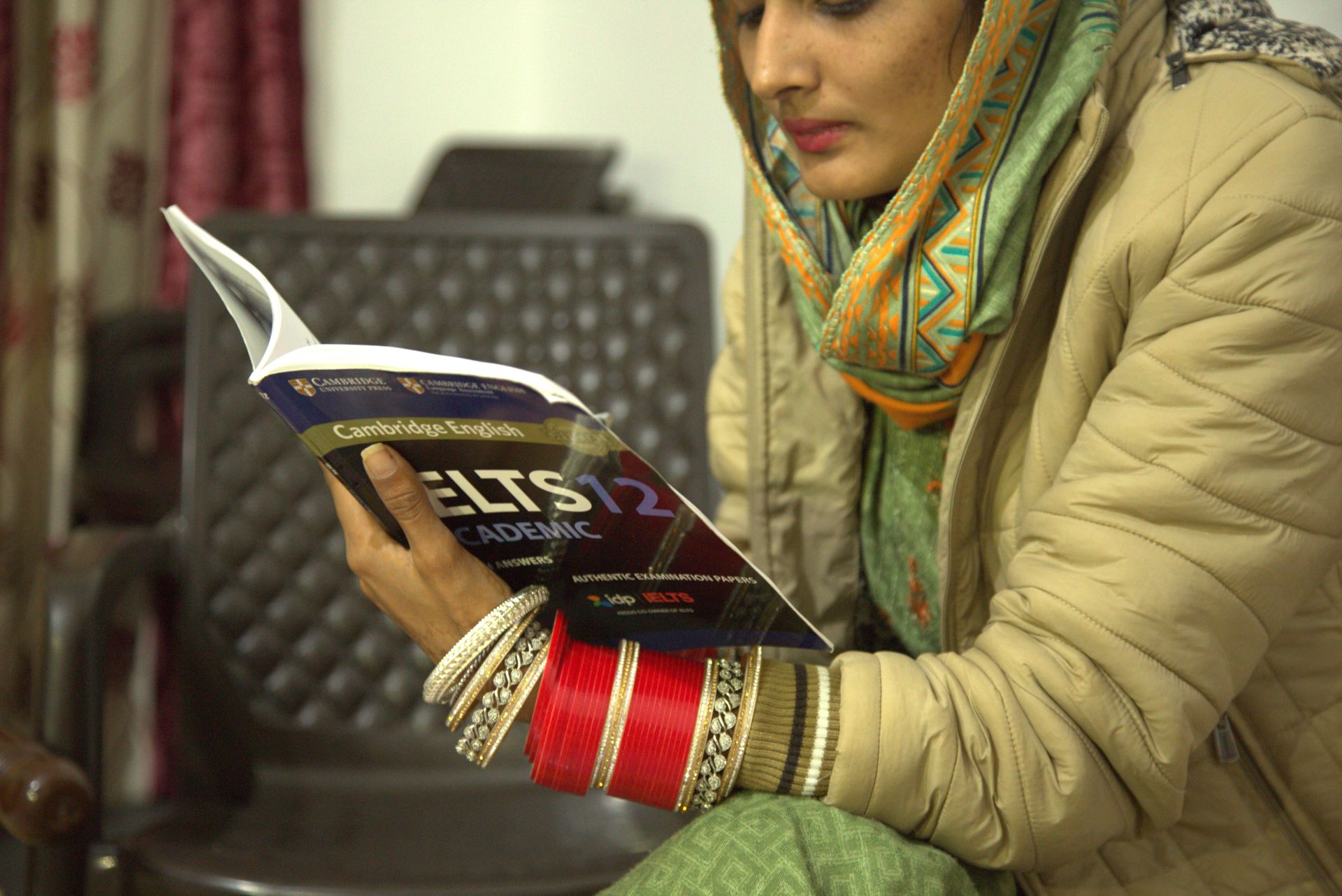

Manpreet sat, filled with dread, in the matchmaker’s cramped, dimly lit office. It was January 2020, only a few months since her family had first put her on the marriage market. They had begun reaching out to distant relatives, downloading matchmaking apps and posting ads in local newspapers, advertising her as a young woman, age 19, who was qualified to apply to foreign universities and needed a suitor who would pay her tuition. To her great anxiety, over a dozen serious offers had already come in.

Manpreet had spent her entire life with her mother, father and elder sister, living in a small home tucked away on a busy street in Amritsar, the second-largest city in the north Indian state of Punjab. Hers was a cloistered existence. Since she graduated high school, she had begun attending a computer class in the afternoons. Otherwise, her family did not allow her to venture out alone or socialize, fearing the men who stalked, stared at and catcalled young women like her in the streets. Create a free account to continue reading Already a New Lines member? Log in here Create an account to access exclusive content.