Daniel Bwanin is barely 20 years old and his youth has already been dotted with searing memories. Wearing a crumpled shirt with a worn-out pair of jeans, he looked at me with bloodshot eyes and recalled how he lost his father, brother and mother — in that order — in July last year, following bouts of armed violence that quickly intensified into a humanitarian crisis in the Christian-dominated agrarian community of Southern Kaduna in Nigeria.

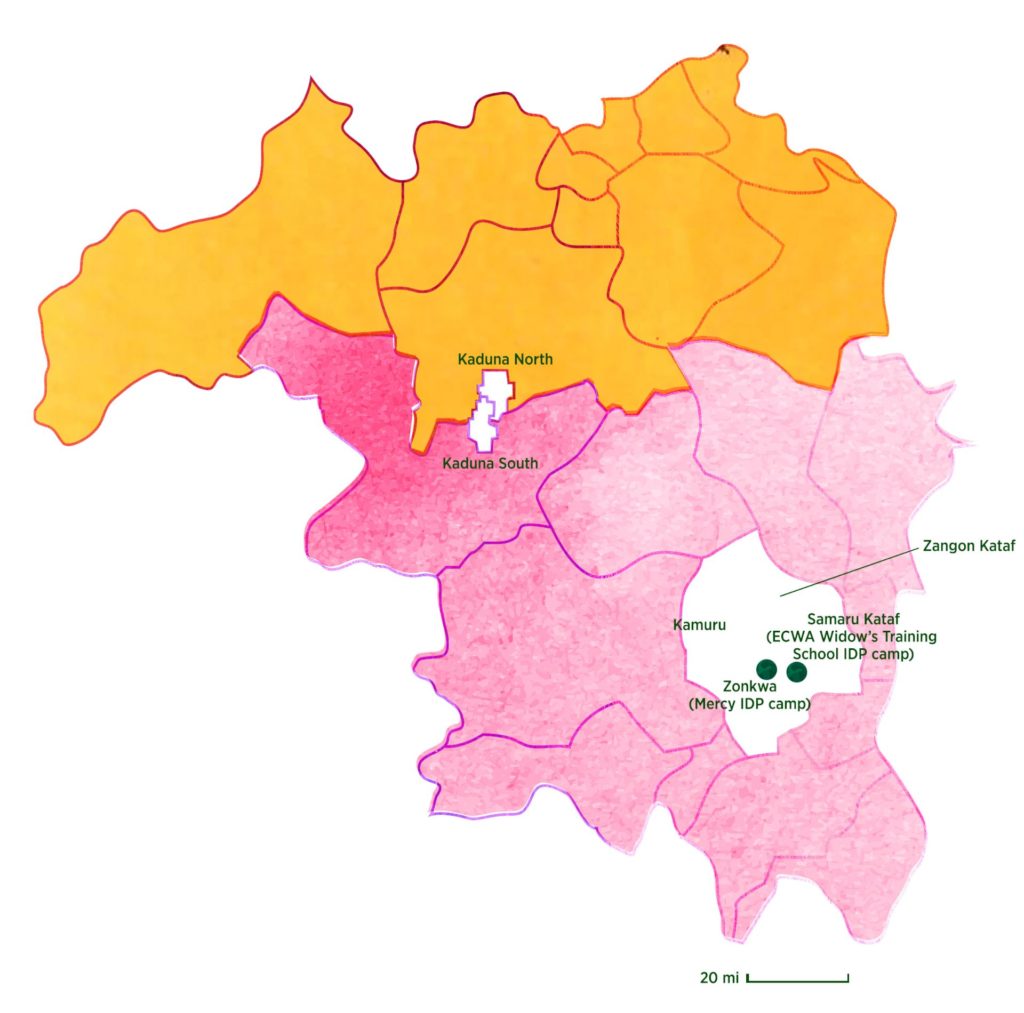

Bwanin’s village, Ungwan Ruhogo, is one of many in the Local Government Area of Zangon Kataf within Kaduna that have come under heavy and constant attacks by Fulani herdsmen during the country’s escalating farmer-herder conflict. However, the crisis over land ownership between the farmers and herders in Zangon Kataf dates back to the 1992 riot between the Hausa and Kataf people under Gen. Ibrahim Babangida’s military regime.

It had all started during the British imperial regime in Nigeria’s Northern Region in the 19th century. The Indigenous Aytap people believed the Hausa settlers took away their land unjustly, when the Emir of Zaria, Dalhatu Uthman Yero, reportedly acquired it but failed to compensate them. It was later converted into the trading settlement of Zangon Kataf, a boisterous market where, although it served both ethnic groups, the Aytap were banned by the Hausa from selling pork and beer. The Hausa settlers wanted to assert their ownership over the land by regulating what their Aytap neighbors could sell.

By 1992, local heads of the Aytap proposed the relocation of the market to a neutral site, but the Hausa opposed this because it would usurp their trading restrictions. Tensions flared, resulting in widespread killings, becoming one of the three most notorious events that shaped the fate of Southern Kaduna. What started as a conflict over land use and ownership has pitted the allied forces of Hausa and Fulani against the Indigenous people of Aytap in Zangon Kataf for the past three decades. These forces have undermined all reconciliatory efforts by the government.

At different intervals, from mid-2020 until March of this year, attackers descended on the villages with an array of sophisticated military-grade weapons and burned homes, churches and schools, killing old men and children. This resulted in thousands of single parents — mostly mothers — as well as grandmothers and orphaned children, like Daniel, seeking temporary shelter in two camps for displaced people in the Kaduna metropolis.

On July 18, 2021, Daniel and his brother, Douglas, then 30, went to the family farm in search of their father, Isiah, who had reportedly been abducted from the farm that morning. Douglas was a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) started in 2013 by Nigerian security forces in order to boost security. The two brothers were joined that morning by several other members of the CJTF. Isiah had been busy stocking the yam produce on a truck with another farmer when they heard a gunshot and immediately ran for their lives. While the other farmer reached home safely and broke the news of how they were chased by some Fulani men, Isiah went missing.

Daniel recalled how their group was ambushed while searching for their missing father, when the soldiers engaged with the Fulani herdsmen in a gun duel. When a soldier was shot at, everyone on Isiah’s rescue mission scampered for safety, except for Douglas, who was hit by the bullet and couldn’t move. “It was after one week that we saw my brother’s corpse by the riverside. We almost didn’t recognize him because his face was disfigured, if it wasn’t for the CJTF uniform of black khaki trousers with a touch of red polo shirt cloth he was wearing during the search.”

They buried him in the forest.

Douglas died searching for his abducted father. Daniel, the second son of the family, lost his mother a few weeks later. She died grieving the loss of her husband and son in one day, and was survived by four other children who suddenly had to fend for themselves.

In their mud-walled dwelling, at the Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA) in Zangon Kataf that provides housing for over 3,000 people, Daniel survives on rationed food prepared for displaced people who share similarly grim stories. Worse, there are several teenagers here who are now being conscripted into the CJTF, willing to risk their lives in ghost communities, ready to counter potential invasion of their farmlands.

Since the 2014 abduction of 276 schoolgirls in the Chibok area of Borno State, to the northeast of Kaduna, there have been sustained kidnappings in northern Nigeria. Although school mass abductions became better known because of the Boko Haram insurgency, some incidents in recent years cannot be linked to the terrorist sect; the armed militia parading themselves as herders adopt a similar style to rain down terror in the north. With the mass kidnapping of over 100 schoolchildren near the Kaduna capital city in 2021, the state of Kaduna became one of the most dangerous for children in Nigeria.

A 2020 report by Universal Basic Education Personnel Audit on Kaduna State disclosed that there were over 500,000 schoolchildren out of school in the state. After a series of abductions in primary, secondary and tertiary institutions, the government decided to close some schools, enlisting them as “identified vulnerable schools.” Many states in the country’s north have been forced to shut down boarding schools in areas prone to violence, in addition to the day schools.

In Kaduna State, the Southern Kaduna Peoples Union, which is an umbrella body for the people of Southern Kaduna, an area severely hit by insecurity, said about 500 schools, mostly primary schools, had been shut down, abandoned or destroyed since 2019. There are over 13.5 million out-of-school children in Nigeria today, with the northern states making up over 80% of the total number. According to Nigeria’s Universal Basic Education Commission, 30% of students drop out of primary school and only 54% transit to junior secondary schools. This damning reality of education in Nigeria has only further deteriorated in the eight years since the country signed the Safe School Initiative, following the abduction of the Chibok girls. The cross-national initiative was in response to the growing number of attacks on the right to education in Nigeria, which highlighted community-level actions and special provisions for schools in high-risk areas.

The UNESCO Convention is recognized as a cornerstone of the Education 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, targeted to make education accessible to all by 2030. It is also seen as a form of empowerment to lift marginalized people out of poverty. However, 244 million children and youth are deprived of education worldwide. 98 million of them are in sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest out-of-school population.

Children in Zangon Kataf have been out of school for two years. Their farms wear a ghostly silence because, with attackers hiding thick in the forest, no one dares farm the land — and yet they want to keep a watch on a small portion so that the entire farm is not taken over by the attacking herders.

In addition to illiteracy and food scarcity, an even farther-reaching problem in the region is the proliferation of arms.

The Nigerian government has claimed victory multiple times over the Boko Haram insurgency that has been ravaging northern Nigeria for the last 13 years. But a series of attacks, masterminded by bandits whom the government declared “terrorists” in January 2022, has turned the region into a theater of never-ending war.

Two recent attacks in Kaduna that unfolded within 48 hours of each other raised further security concerns. On March 26 last year, attackers tried to penetrate the state airport through the runway, killing one official before the authorities drove them away. Two days later, a train line running from Abuja, the national capital, to Kaduna, came to a halt for three weeks after armed militias planted bombs on its tracks. At least eight passengers were immediately killed when the bombs detonated.

Barely a day after the train attack, bandits invaded the village of Ungwan Bulus in Southern Kaduna and abducted 25 people. The village was significant, as it jointly hosts the Kaduna rail link station in the neighboring Rido village that connects the Kaduna refinery to southern Nigeria, where the country’s primary resource, crude oil, is found. Attacks in Southern Kaduna now appear to be more geared toward economic and political dominance than territorial control.

Hailing from the conflict-torn Kaduna, Emmanuel Nga lost his mother, Veronica, in one of the most traumatic ways: She was burned to ashes in her own house. Then other people, including the village head, were killed. Emmanuel could well have died himself, but he hid on the yam farm while the attack lasted. Since he had already lost his father to an illness, he fled with his uncle’s wife, his new godmother, Angelina Sule.

Living at a widow’s training camp in Zangon Kataf, Angelina was one of many women forced to leave the village of Atakmawei at the end of 2021. Apart from tending to her 14-year-old nephew, Emmanuel, she also had to look after her little children. Like many other widows in the camp, she swore not to return home until peace was restored.

Ironically, people living in the camp’s confined space say they find more quietness than at home, despite the poverty they have to endure. They eat from a single pot and look forward to every stranger’s visit at the center for displaced people, as visitors come bearing gifts and donations: food items, buckets, laundry soap, money and clothing.

Gabriel Joseph, the camp coordinator, said, “Hello, hello” to scores of women as they nestled together to select from donated items. Later, as we discussed the state of affairs, Joseph lamented how cash donations have dwindled because of the economy. “About two weeks ago, the women braved a lack of sugar, palm oil, vegetable oil and food spices at the camp,” he said. Food was donated by those who managed to farm nearby, but the women had no money to buy other items they needed. “Our people are going to suffer this year a lot,” he said. “If you have money here and you are building a house, it is nonsense. No one can live in the house now because of insecurity. People are using money to buy what will protect them.

“The children, who have dropped out of school, are going to their parents’ farms and harvesting over 20 to 30 bags of maize, which they sell to buy guns,” Joseph continued. “If 30 children are working on the farms, the other 30 are on a vigil, guarding them against any attacks.” This strategy was adopted after a series of attacks, in the days since Daniel’s father was abducted on his own farm. He is still missing and is believed to have been killed.

In the heart of Zokwa town lies a larger challenge — how to feed over 4,000 women and children at Mercy Camp, another home for the displaced in Zangon Kataf. I rode on a motorcycle with Titus Augustine, a 27-year-old graduate of Kaduna College of Education, to his desolate village of Matyei, where he recounted the worsening crisis between the farmers and Fulani pastoralists in Zangon Kataf. As we arrived, he sat with his friends and reminisced on the memories of how, within one week in July 2021, the villages of Ungwan Ruhogo, Matyei and Gan Gora as well as other non-militarized villages saw bullets flying over their roofs day and night. It started with Ungwan Ruhogo. Three days later, the attackers moved to Matyei, where Titus lived with his parents. That night, he went with the other youths to patrol and “alert people whenever the armed militias were drawing near.” Little did he know a tragedy would strike home.

“When we heard the first gunshot, I ran to my mother’s room to wake her and my sisters up. I didn’t realize my father didn’t follow us on the patrol. The Fulani caught up with him sleeping,” he said. He was not only shot but burned so they could be sure of his death. “I saw the spilled blood on the wall before they burnt him with his mattress,” said Titus.

Today, the young graduate has nothing to do but watch over his late father’s inheritances. If he and his friends in similar situations fled their farmlands and homes, they would be giving the marauding herders an opportunity to occupy their land for open grazing. The only place to go, apart from their unsafe homes, is the overpopulated camps for the displaced, built by churches and private individuals, whcih are largely reserved for women and children, rather than male teenagers or adults.

A friend of Titus’, Nuhu Emmanuel, who was separating corn from its husks as we talked, justified the use of arms by male teenagers for “mere protection and immediate resistance.” Depending on the number of people left in the village every night, these young men run up to three night shifts as watchmen to ensure attackers do not sneak into the farms overnight or alert their resting colleagues during midnight attacks. “If there are many of us in the village, we could have up to three groups of men; each group can stay awake for three to four hours while the rest will sleep,” Titus explained. “But all of us don’t sleep at once. Some have to be awake while some others are sleeping.”

A single rifle costs around 25,000 nairas ($55), equivalent to the market price of two bags of harvested maize. A report by the London-based Conflict Armament Research organization on firearms recovered from groups linked to the herder-farmer conflict in Nigeria showed that most of these guns are manufactured by local blacksmiths across the northern corridors, while other sophisticated weapons are imported from neighboring countries.

Last August, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari transmitted two bills to the National Assembly to curb the proliferation and illegal possession of firearms, but lawmakers have yet to pass the bills for final approval. Despite the bills, Ado Doguwa, a member of the Nigerian House of Representatives, recently suggested civilians should be allowed to bear arms to protect themselves and their resources.

Titus Avele, a security expert and director of a private security firm, fears that empowering civilians with arms could lead to reprisals and make the nation’s capital ungovernable in no time. He instead proposes a “quick response” by the Nigerian military to such attacks. “When people feel the need to carry arms for protection, it shows that the government has failed in its duty to keep them safe,” he said. Avele’s suggestion for handling insecurity in the North, however, seems unconventional. Some of the states’ governors are asking their citizens to bear arms while the problem lingers. The governors of both the states of Zamfara and Katsina have called for self-defense in the past year.

Added to this is the stark reality that the military, which ought to rise to the occasion, is stretched thin and unavailable in some of this volatile terrain. The watchmen in Matyei told me no soldiers were deployed to their village. They had spoken with soldiers posted in Ungwan Ruhogo, who explained that Matyei was less populated, unlike other villages where men and women had remained to sell their produce on market days. Furthermore, the exit bridge in Matyei, not far from where I met with Titus and his friends, was under construction. Early in 2022, in the last week of February, the former bridge, a wooden structure, was burned by attackers to prevent the watchmen from escaping.

The crisis in the north has already overstretched members of the Nigerian military, forcing them to run for their lives like unarmed villagers when the terror gangs strike. According to the Violent Conflict Database from Nextier SPD, a Nigerian NGO, from October 2020 to September 2021, the north-central region, including the state of Plateau, remained the hotbed for farmer-herder conflict, while the northwest, including Kaduna, was the most violent in terms of casualties per incident.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, a US-based NGO, corroborated Nextier’s findings, confirming that armed militias proved deadlier than Islamists in 2021. Organized political violence involving militia groups increased by 50% in 2021, compared to 2020, with over 30% of militia activity occurring in Kaduna State. Over 2,600 civilians were killed by these militia groups in 2021, higher than the number killed in the same year by Boko Haram and its splinter faction, the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP).

As several African countries reel with internal crises, Russia has seen an opportunity to expand its agenda and systemically displace Western influence on the continent. It is doing so by bartering arms for resources such as crude oil. Nigeria, the centerpiece of Africa, is caught up in this mix. According to the Arms Transfers Database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia was the largest arms supplier to Africa between 2017 and 2021, accounting for 44% of major arms imports. Apart from Nigeria, Angola and Ethiopia are among the largest arms importers in sub-Saharan Africa.

Unless the Nigerian government contains the non-state actors in the north, unregulated distribution of both indigenous and conventional arms in Kaduna is likely to drag Nigeria into full-blown war. Orphans like Daniel and Titus thus live in perpetual uncertainty, with little hope for education.

While Titus is fighting hard not to join others in returning to the razed homes and taking up arms, the odds are against him. He will soon have to give up his space for the more vulnerable at the densely populated camp. The meager food supply at the camps forces many teenagers and young adults to brave their fears and return to their farms in order to afford a little more.

Once Titus realizes that his counterparts who are farming eat better than him, he is likely to follow suit. Though he aspires to study theater arts at university, at this moment in life the easiest way for him to survive is to relinquish his dream, defend his village and farm on his late father’s land. Similarly, Daniel doesn’t know what the future holds for him. He remains under the watch of his uncle’s wife, living in the camp. “I would like to further my education and study theater arts because that is what most of my friends are doing in the university elsewhere,” he says. But it is more likely that both he and Titus will pick up arms to sustain themselves and protect their ancestral lands.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.