In the early hours of July 24, residents of the remote mountainous regions of Toudja and Beni Ksila, in northern Algeria, woke in a hurry as a wall of flames approached their villages. The heatwave that had gripped the whole Mediterranean basin in July, sending temperatures into the 120s, had dried out the dense groves of wild olive trees and tall spring grasses that covered the hillsides, providing ample fuel as the wildfire raced down the steep slopes toward the sea.

Villagers rushed to gather a few belongings and animals, then fled toward Oued Das, the small resort town on the coast below them. Some made it to the water’s edge before the flames engulfed them. Others were swept up in the blaze.

“The flames were gigantic, coming at high speed from the mountains,” a young construction worker named Jamel tells New Lines just hours after the fire. “A man, his wife and their baby were driving down from the top of the village, but the flames caught up to them,” he says. Their bodies were discovered in the burned-out hull of their car.

From the water’s edge to the mountaintops, the charred landscape is still smoldering. A few hours after the fire, about 20 men gather in the parking lot of a hotel restaurant, which has been destroyed. Two of them, haggard, are wearing bandages on their arms and legs to protect fresh burns. Along with others, they tried to extinguish the fire that was raging around them with what they had on hand: buckets.

At Oued Das, a military base overlooks the Mediterranean coast.

“There were no firemen, no ambulances. Only a military vehicle intervened, trying to save the soldiers who were fleeing,” Jamel laments, looking at the charred cars of tourists in the hotel parking lot. The force and speed of the fire took the whole region by surprise; only the owner of the hotel’s restaurant had been able to react in time, hiding his customers in the cellar at the last minute as the flames swept through town.

For the third year running, Algeria is facing a series of deadly wildfires. The fires in the Kabylia Mountains, fanned by violent winds, left at least 34 people dead and 325 injured, with 1,500 others evacuating their homes, according to Algerian authorities. It took security services several days to find and tally the bodies in the burned-out houses spread across the hilltops. Last year, at least 38 people died in wildfires raging in the country’s east, and a massive wildfire in the Greater Kabylia region in 2021 killed 103 people.

Global warming is contributing significantly to the conditions that cause and exacerbate these megafires. A special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that focused on how global warming was affecting different areas of our planet noted that the Mediterranean was particularly susceptible to the effect of rising temperatures. But, as the mercury rises higher each summer and Algerians brace for the flames, there is another problem many point to — the negligence of the Algerian state. Decades of poor land management practices, combined with a lack of firefighting resources and community awareness or willpower to reduce fire risks, have left millions of Algerians exposed to the increasing threats of wildfires.

At the height of this year’s fire season, New Lines went to the frontlines of Algeria’s wildfires to meet the people who were alone in the face of the flames. Some lost everything. Others have turned to indigenous practices of land management and planting protective crops, like prickly pear, to shield themselves where the state has failed to.

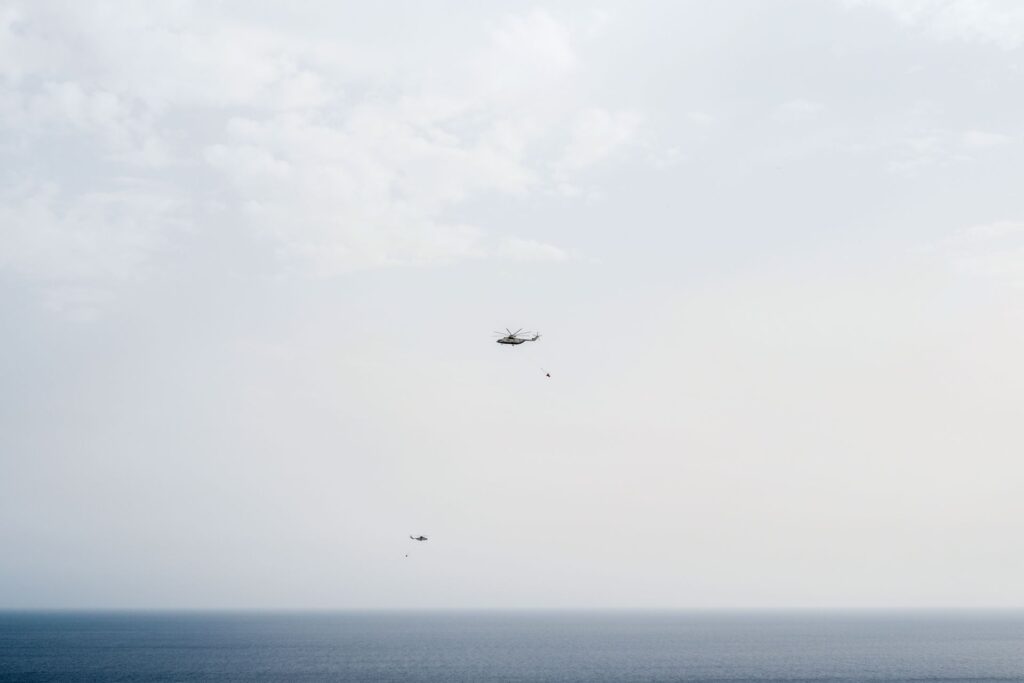

By the morning of July 25, a day after the deadly fire in Beni Ksila, three army helicopters with firefighting equipment are flying rotations between the port of Ait Mendil, five miles up the coast from Oued Das, and the Souk El-Djemaa region, where fires are still burning in Little Kabylia. Following the fires in 2021, Algeria placed an order with Russia for four Beriev Be-200ES water bombers, each with a capacity of more than 3,000 gallons. But the war in Ukraine has slowed production, and Russia has only been able to deliver one aircraft, which has still not completed its test campaign, according to the specialist website MENA Defense. As a remedial step, Algerian authorities have leased six fire-fighting aircraft from Chile, according to the newsweekly Jeune Afrique.

The small village of Ait Oussalah was the hardest hit, with 16 deaths. As the helicopters fly circuits out over the Mediterranean, Ilyas, a local resident, says he hadn’t heard from his cousin since the blaze started. “I don’t know if he’s dead or in the hospital. We’re still looking for him. And my uncle was burned to death, there’s nothing left but ashes. The village of Ait Oussalah has been razed to the ground, it’s become an inferno.” The bereaved population hastily organized funerals to avoid the bodies decomposing in the sweltering heat. Their grief quickly gave way to anger: “The state does nothing, it’s because of it that we’re dying!” Ilyas says.

Fifty miles away, the men of the village of Sahel are busy collecting food, water, clothes and mattresses for a humanitarian convoy to the affected areas. “We made announcements on Facebook and over the village loudspeaker to warn the population,” explains Hakim, a fireman originally from Sahel and the president of the Tiwizi (which means “mutual aid”) solidarity association.

Late into the night on July 27, residents line up outside the village solidarity association, dropping off food and clothing. Even people of limited means bring warm bread they have prepared. The houses in the village alleyways, teeming with people wanting to help, are painted by young artists. A grandmother dressed in traditional Kabyle garb carries a large box of foodstuffs on her head up the steep slope of the main street. “Let me help you,” says Hakim. In 2021, the village of Sahel was surrounded by flames during the great Kabylia fire that killed 103 people. The trauma is still fresh in people’s minds. Hakim remembers the outpouring of solidarity that came to their aid.

“I have a duty to help too,” the fireman says. “In 2021, the whole of Kabylia rallied round us. This year, we have to do our duty and pay our dues.” About 40 men are mobilized to distribute all the donations in 16 trucks and pick-ups. As they pack the goods, Hakim’s cousin, the former village chief, barks instructions: “Take only the new things. Used clothes will be put aside for the next convoys.”

Hakim was on duty at the fire station in a neighboring town the day the devastating fire swept through in 2021.

“I called our village committee to tell them to get ready, because we didn’t have enough resources, and we couldn’t help them because we didn’t have enough trucks,” he said. They had only two fire trucks and a handful of light vehicles for a region of 22 villages spread out over 10 square miles of mountainous terrain. On Aug. 9, 2021, more than 250,000 acres went up in smoke, razed to the ground. “In five minutes, literally, the fire covered between 6 and 9 miles,” he recalled. “The only thing to do was to run away and let it burn. Because it’s impossible to control the fire. It’s like a tsunami.”

The whole village has been mobilizing for days to get the trucks packed and ready to send to those now facing the pain of loss they experienced only two summers ago. Hakim, who spearheaded the effort, is running on three hours’ sleep and is due at the fire station for his shift shortly. He has entrusted his vice president, Rachid, with the task of leading the convoy to the disaster area. As they pull out, Hakim snaps a few pictures of the trucks, some of which have banners reading: “Sahel Village Committee. Solidarity with fire victims.”

As the humanitarian convoy passes through the villages, people greet them, shouting, “On the way to Bejaia!” Not far from the disaster zone, the convoy crosses the outskirts of a smoking garbage dump, in the middle of a forest where the consequences of the 2021 fire can still be seen. Waste management is at the heart of the problem of forest fires in Algeria. “The state does nothing to collect waste. The village committees designate a place in the middle of nowhere for the garbage trucks to dump the waste and burn it,” said one young local man.

After a five-hour drive through the steep mountains of Kabylia, the villagers of Sahel finally reach Souk El-Djemaa. As they come up over the rise, a smoldering, lunar landscape stretches as far as the eye can see. Other groups from Kabylia join Rachid’s convoy. A long line of vehicles follows a winding path through the charred forest. Rachid, in the lead vehicle, stops at the top of a pass to join his local contact, who is in charge of the crisis unit set up quickly in the wake of the fires.

“The village of Ait Oussalah is not accessible today. It’s being cordoned off by the police to look after the funeral,” the head of the unit explains to Rachid. “You should send two of your trucks to Talla Oumallou, a small village that has not yet received any aid, and the rest of your convoy to Souk El-Djemaa, where donations for the region are centralized.”

As Rachid’s convoy rolls down from Ait Oussalah, the aid workers slow down to film the disaster through their vehicle windows. They watch as about 100 people flock to the village of Ait Oussalah for the funeral. The smell of decomposing flesh mingles with that of burned trees. Rachid’s convoy continues toward Souk El-Djemaa. At the entrance to the village, a long queue slows them down. Several vehicles have stopped to attend Friday prayers. Over the loudspeakers, the local imam gives a sermon in tribute to the victims of the fire. His trembling, emotional voice echoes through the mountains.

Unlike Ait Oussalah, which was devastated, Souk El-Djemaa was spared the flames, but the region is no longer connected to water and electricity. As the adults of the town attend the funeral, local children help the people of Sahel unload the trucks at the town’s elementary school, which has been transformed into an emergency accommodation center and a collection point for aid. Cases of bottled water pile up in the school playground. By the time they finish, Rachid is exhausted, but relieved to have gotten the supplies in safely.

“After what we experienced in 2021, it was important to be here,” he said.

In the village cafe, a dozen men from Souk El-Djemaa gather after prayers. Amid the smoke-blackened walls, Ahmed, an older man with heavy burns to his face, arms and legs, is sitting by a window overlooking the devastated landscape.

“My son wanted to come with me when we saw the fire coming,” he says. “I wanted to save my donkey in his hut. When we got there, I saw my neighbor in trouble in the middle of the flames, so we went to help him. The fire was moving so fast that we were surrounded.”

He had brought towels and a bottle of water with him and acted quickly. “I told them to wet the towels well and put them on their faces. Then we lay down on the ground and the fire came over us. We managed to survive.”

The fire is at the heart of the discussions in the cafe. One man stood up and said, “In less than two hours everything was burned. I’ve rarely seen such a strong wind. We have fires every two years, but this was unheard of!”

“It came from the landfill,” adds another. It’s a common refrain. But while improper waste infrastructure is part of the problem — many small villages have unmanaged dump sites at the edge of town where waste of all sorts is left, unprotected, in the heat — Karim Tedjani, an Algerian ecologist, says mismanagement of wildlands in areas where wildfire is part of the ecological life cycle is the greater problem. “The lack of maintenance and rational use of forested areas means that they accumulate large quantities of biomass” — a thick carpet of dried grasses, fallen tree boughs and dead leaves — “which in the medium term can become a veritable fire bomb,” he explains.

There’s little upstream maintenance of the land, he says, whereas just a few generations ago, regular, manageable fires were a part of a cycle of growth and renewal that the region’s inhabitants participated in.

“Spatial planning policy needs to be rethought in light of the new climatic conditions of the 21st century,” he says. As the planet warms and the fires grow worse, buffer zones between wildlands and inhabited areas and crops need bolstering, and strategic maintenance — prescribed burns, brush-clearing or other tactics — need to become priorities.

In the wake of successive deadly fires and faced with the State’s inaction, conspiracy theories often percolate.

“It’s the Algerian state that’s trying to murder the Kabyles,” one man tells us.

As bereaved families bury their dead, villages begin clearing brush. On the roadside, diggers flatten the undergrowth. In the village of Ath Yenni, scarred by the fires of 2021 that claimed four lives, the inhabitants are keen to turn the page: “It’s behind us,” says one farmer. A sense of fatalism can be felt in these villages, which lie far from Algeria’s major urban centers.

“Fires are everybody’s business,” says Mohand, a 68-year-old man sitting at a cafe table. “We need a land tax system like in France. If the land is farmed, the owner could be exempted from tax. This would encourage people to cultivate the land and protect the villages from fires.”

He says novel models, like agritourism, which could improve farmers’ incomes and better protect the land, have been proposed to the “wilaya” (administrative division) of Tizi Ouzou, but that they’ve stalled. “The Directorate of Agricultural Services, the wilaya and the government are blocking these projects. For no reason,” he says.

Eastern Algeria has not been spared. In August 2022, the Souk Ahras region was the scene of a megafire. According to Gamal Touahrieh, general director of forests, more than 24,077 hectares went up in smoke. Also caught in the fire were the wife, daughter and three grandchildren of Salah Aaouaitia, a shepherd who now lives in a makeshift shack of cinder blocks and corrugated iron on a hillside surrounded by wild olive trees blackened by last summer’s fire.

Aaouaitia’s daughter had come for a visit from a nearby city and wanted to see the house at the bottom of the hill where she was born. This dive into her memories was to prove fatal. Aaouaitia was up in the mountains with his small herd of goats when the blaze started.

“When the fire came, I ran toward our old house, but I fell down,” he recalled. Aaouaitia tried to get up again. “I’d cut my forehead open. When I got up, I staggered because of the pain and the smoke. Then I passed out.” He couldn’t save his family. The firefighters at the top of the hill were blocked by the flames. It was thanks to neighbors that Salah was able to be pulled out.

Today, the only reminders of his family are a few colorful textiles spread across his burned-out shack and a stack of legal paperwork. Along with his two sons, Aaouaitia is fighting two simultaneous legal battles, one against the arsonists and another against the Algerian state, which now wants to build housing developments on the land where Aaouaitia lives.

Aaouaitia’s son, Toufik, opens an envelope and pulls out a stamped official document dated August 2022, a few days after the fire — a court order to leave the land.

“We’ve been living on state-owned forest land since 1970,” he explains. “They want to build social housing there. We’re being forced out,” he says, despairing. Salah says he doesn’t have social security, making it difficult to be rehoused. He says his son has sent requests for an audience with his district representatives but has been ignored. (New Lines’ requests for comment from the local officials also went unanswered.)

The second case concerns the fire. Toufik opens a second envelope containing a court report from the Sidi M’hamed court in Algiers. On it is a list of the four men found guilty of setting the fires.

“I forgive them,” murmurs Salah, surrendering himself to God. According to Toufik and Salah, as victims, the court has offered them compensation. “But you have to pay a lawyer for that. We don’t have the money,” Toufik says impassively. It also requires travel to Algiers, hundreds of miles away, which Salah says wears him out. According to Touahrieh, the general director of forests, the compensation process in the wilayas of Guelma and Souk Ahras was completed in September 2022. Salah lost 24 goats in the fire; he says the state gave him two goats as compensation. “The problem was that they weren’t used to this climate. They were Alpine goats, so I sold them,” he said. Today, Salah owns four goats, who he grazes on the charred hillside. Despite the tragedy, Salah still wants to live on his land.

“I’ve invested my whole life here,” he said.

The residents of Souk Ahras have criticized the Algerian government’s management of firefighting in the area. Even those involved in the efforts admit there is a crisis in the management of wildfires. Bachouche, a local firefighter, was just a few yards from the site where Aaouaitia’s family perished and almost lost his own life. Bachouche, an athletically built man with a shaved head who has been a firefighter for a decade, doesn’t mince his words: “We have a command and staffing problem. I’d been on duty for 24 hours when my unit was called out to the southern entrance to the town of Souk Ahras. The command recalled everyone: those on holiday, those on rest, even those on sick leave.”

On the afternoon of Aug. 17, 2022, as the fire engine careened toward the blaze, Bachouche did a Facebook live broadcast to warn people of the extent of the fire. His crew headed to a gas station on the outskirts of town that was separated from the forest by a flimsy fence and posed a major threat. Should the fuel tanks ignite, a catastrophe would ensue.

“We lined up the tankers between the fire and the petrol pump,” Bachouche recalls. “When the fence fell, people on the other side were trying to escape the flames. They were pushing us to get out. Our main unit needed more manpower.”

Below, on the hillside, among the olive trees still scarred by the flames, Bachouche brought us to see the place where he thought he would die. “I fought the flames here for four hours. But the fire kept going. Because I was so tired, I thought I was facing smoke, but the flames were hiding right behind me,” Bachouche recalls. “Out of fear, I stepped back, and the pressure of the fire hose broke my collarbone. I was knocked to the ground, dropping the hose. Civilians took over. I felt terrible because of the pain and the heat. I hadn’t recovered from the last mission either. As I crawled back up, the fire was gaining ground. My colleagues and some civilians trampled on me in panic. When I got to the road, everyone was fleeing and I lost consciousness. A civilian managed to pull me by my injured arm towards my colleagues.”

According to Bachouche, that same day, 26 communes were hit by fires at almost the same time.

“It was complicated to disperse the firefighters to all the fires,” he says. “There weren’t enough of us.”

With the increased intensity of each year’s fire season and lack of support from the state, some of the high mountain villages of the region are taking matters into their own hands. Sahel, which sent the convoy of aid to those affected by the recent fires, has set itself up as a model village. The facades of the houses have been painted by street artists from all over Algeria, often highlighting ashtrays on various street corners, with signs reading: “Empty the ashtray when it is full.” Selective sorting bins have also been installed to collect plastic and improve waste disposal. In the heart of the village, a room painted red and yellow houses emergency equipment, including fire extinguishers, fireproof clothing, shovels, masks and gloves.

Almost a decade ago, the residents of Sahel had a revelatory moment when a local teacher organized a conference focused on protecting the environment using ancestral traditions, including fire management. They didn’t need to wait for the state to arrive in case of an approaching wildfire; they could take preemptive action themselves.

In the house belonging to the Sahel women’s association, Naouiza and her mother are weaving clothes for the forthcoming festivities. In a few days’ time, the village will be hosting the prickly pear festival. In the sweltering heat, Naouiza seeks shade. She explains to New Lines what makes her village so special in terms of environmental protection and firefighting.

“Thanks to our protective equipment and water supply, we were able to mobilize during the fire of 2021. We didn’t wait for the fire brigade to arrive,” she says proudly. The women’s association, set up in 2003, and the village committee are working hand in hand to preserve their land. “Every late spring, we hold an extraordinary general meeting to vote on clearing the undergrowth in the village,” she explains. “All the large trees have to be pruned or cut back to avoid posing a danger. Wooden enclosures are forbidden. It’s also forbidden to burn anything from June 1 onward and to bring hay or inflammable products into the village.”

At the beginning of each summer, the villagers have a duty. They clear their land and help to clear the undergrowth around the village to prevent fires spreading. It’s a method that is bearing fruit. In 2021, when Kabylia was engulfed in flames and the region was counting its dead, Sahel was an exception. Surrounded by the blaze, the village resisted. “We had a big fire all around us, there were huge flames, but fortunately in the village we had few injuries and no deaths,” says Naouiza.

Wearing a red “djellaba” (a long outer robe), 43-year-old Aida joins Naouiza. This mother of three, who is also a member of the women’s association and the environmental association, talks about her experience: “I learned a lot of things when I joined the environmental association, such as waste management, composting, making potting soil from household waste and recycling.” Since 2015, this association has specialized in environmental protection, initiated by the hikers’ association, which sought to democratize environmental issues. “Following the success of all these projects, it would be a shame for us to go backwards. We have to keep moving forward. As soon as there’s a letup in the village, we women get the movement going again,” Naouiza adds.

To this end, Aida has launched a new project, drawing on the knowledge of her elders. “We’re going to circle the whole village with a series of two rows of cacti,” a method that creates an insulated barrier. “It’s an effective way of fighting fire. Cacti are very water-rich and hardy. My mother passed on this information to me, so we’re going to follow her ancestral techniques to protect ourselves,” she says, standing on the outskirts of the village, facing some large prickly pear cactuses.

The prickly pear is a natural firebreak that originated in Mexico and has been adapted throughout the Maghreb. Aida contemplates the boundary between the village protected by this line of cacti and the trees recovering after the fire, and concludes: “These prickly pears were planted by my grandfather.” To ensure that the innovative initiatives continue, the local residents have also suggested that the children become “environmental police officers.”

“As soon as adults throw rubbish on the ground, a fine is imposed by the children and the money goes into the village coffers,” explains Aida as she walks alongside Naouiza and Melina, a 10-year-old girl. “We used to give out a lot of fines, but not any more. Nobody throws papers on the ground anymore!”

Naouiza hopes that the next generation will always be involved. When she comes of age, Melina will be able to choose between being a member of the women’s association or the environmental association. When Naouiza asks her which she would choose, the young girl answers without hesitation: “Environment.”