Until some years ago, Nora Solomon Sherry Chandgavkar would spend hours toiling in her kitchen preparing chik-cha halwa. Halwa is a chewy, gelatinous sweet popular in India, and different cultures have their own recipes. This one — made with wheat extract, sugar, coconut milk and edible rose coloring — is prepared by the Bene Israel, the largest Jewish community in India, during Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

Since preparing it was a laborious and time-consuming process, the 66-year-old home chef instead offered us halwa made with corn flour when we visited her home in Thane, a city barely 14 miles from the financial capital of Mumbai.

But what was unique about these halwa recipes was that they did not contain ghee, a type of clarified butter and a staple in Indian households. Often halwas are loaded with dollops of ghee, but Chandgavkar instead used vanaspati, a refined vegetable oil, because kosher rules do not allow meat dishes to be had alongside dairy foods.

“There’s chicken curry for lunch, so I can’t serve dessert with ghee,” she explained.

Warm and nongreasy, unlike the ones we are used to eating, the sweet had a rarefied scent of saffron and the earthiness of coconut milk, which was Chandgavkar’s star ingredient, a recurring element in her food. Just earlier for lunch, she had served us narali bhaat, rice stewed in coconut water and coconut milk, along with saandhan — steamed semolina and coconut dumplings.

Coconut permeated her cooking not only because it was an alternative to dairy milk but also because of the community’s deep roots in North Konkan — a coastal region in the west Indian state of Maharashtra — where coconut trees grow aplenty and the ancestors of the Bene Israel sought refuge over 2,000 years ago. As they interacted with other communities in the region while remaining cut off from the rest of Jewry, it led to the creation of a unique Indian-Jewish identity. And their cuisine, which draws heavily on Konkan while observing kosher rules, reveals how Bene Israel culture is a marriage of both faith and community.

Today, the Bene Israel still dot a few coastal towns in the North Konkan region but have also fanned out to the cities of Mumbai, Thane and Pune in Maharashtra, and to Surat and Ahmedabad in Gujarat. They form the core of the Jewish demographic in India, which has been shrinking since the 1950s after Israel began granting full citizenship to all Jews, sparking waves of emigration among the Bene Israel. Shortly before, in 1947, India and Pakistan had both gained independence. Tensions remained high following the traumatic Partition, which made the local Jewish community unsure of their place in these two nations.

By the turn of the 21st century, India’s Jewish population — estimated to be around 22,000 in the 1941 census — stood at 4,650, according to the 2001 census. But in Israel, the Bene Israel form the majority of the approximately 85,000 Jews of Indian origin living in the country, according to the Indian Embassy in Tel Aviv. However, as their numbers gradually declined in India and the local Bene Israel assimilated with Israeli society, those remaining in India have tried holding on to their coastal roots through food and memory.

India is home to several Jewish communities settled in different parts of the country, whose ancestors migrated in different waves over two millennia, such as the Malabaris and the Paradesis in Kerala, and the Baghdadi Jews, who made the cities of Surat, Mumbai and Kolkata their home in the 19th century. As mercantile communities, both the Paradesis and the Baghdadis forged stronger economic connections with the rest of the world and had more financial resources at their disposal. The Bene Israel remained largely unknown as their assimilation with the locals made them indistinguishable.

The Bene Israel are said to have come to the subcontinent around the same time as the Malabaris, roughly before 70 CE, said Sifra Lentin, author and historian at Gateway House, a Mumbai-based foreign policy think tank. While the Malabaris possessed epigraphic evidence of their history, the Bene Israel, which is Hebrew for Children of Israel, had none, she said.

“Their origin story has been orally passed down,” said Lentin, who was born and raised in a Bene Israel family.

At the heart of this legend is a shipwreck that is said to have occurred near the village of Navgaon, about 5 miles from Alibaug, a coastal town south of Mumbai, and seven men and seven women are believed to have survived it. While they are said to be descendants of one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, there’s no archaeological evidence of their arrival, except for an obelisk-type of memorial with a base of the Star of David, erected as recently as the 20th century in dedication to the legendary shipwrecked families in Navgaon.

For nearly a millennium, the Bene Israel remained a marooned community, isolated from mainstream Judaism, and sustained their religious identity through oral history and the observance of the Jewish Shabbat and the Holy Days, said Lentin. The first documented evidence of the Bene Israel, wrote Joan G. Roland in her book, “The Jewish Communities of India,” was in 1199, when celebrated Jewish philosopher and physician Moses Maimonides, a spiritual leader of the Jews of Egypt, referred to the community in a letter to the rabbis of Lunel, in present-day France. “The Jews of India know nothing of the Torah and of the laws, nothing save the Sabbath and Circumcision,” he wrote.

Historians say that three events spurred religious revival and the subsequent integration of the Bene Israel into the Jewish world. The first is attributed to David Rahabi, a Jewish gentleman, possibly from Egypt, who lived with the community sometime in the early medieval period and retaught them the basic tenets of Judaism, said cultural historian Pushkar Sohoni. The second revival, said Lentin, occurred in the 19th century with exposure to the Baghdadi Jews and Anglican missionaries — many of whom had immigrated to present-day Mumbai — who encouraged them to study Hebrew and translated Jewish religious texts to Marathi. The third was the formation of the State of Israel in 1948, said Sohoni.

But the fact they remained cut off from the rest of the Jewish community for so long allowed room for traditions that didn’t necessarily need religious sanctioning. Indianness defined their lifestyle, including in their style of dress, food and cultural practices, said Esther David, a leading Indian-Jewish author and artist who has documented Bene Israel’s food history in both her fiction and nonfiction works. An 1874 illustrated Poona Haggadah, a Jewish text that sets the order of the Passover Seder, depicts a scene with women wearing traditional Maharashtrian saris and jewelry and baking the Indian matzo, an unleavened bread known as bin-khameer-chi-bhakhri in Marathi.

Food and offerings made during religious festivals show a distinct likeness to the meals prepared by the local Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Parsi communities in this coastal region. For instance, the crescent-shaped kippur-chi-puri, a sweet, deep-fried bread made with grated coconut, semolina and nuts, with which Bene Israel break the fast of Yom Kippur, is reminiscent of both “karanji,” a sweet, deep-fried pastry prepared during Diwali in Maharashtra, and “neureos,” served during Christmas in neighboring Goa. The drink “tandalachi pej” — made by boiling broken rice in water with salt and coconut milk and consumed by the Bene Israel on the morning of Passover (“Pesach” in Hebrew) — is similar to the “pej” this writer, a Roman Catholic with roots in the coastal town of Karwar in Karnataka, has on Good Friday.

The platter that the Bene Israel make for the Malida service — performed during auspicious ceremonies such as getting a job, buying a new home, an engagement or a wedding — is unique to the Bene Israel community and is not made by any other Indian-Jewish community. The offering — which includes a sweet dish prepared with flaked rice, freshly grated coconut, sugar, red roses and fruits like dates, apples and banana — is made to the Prophet Elijah, a looming, guiding presence in the lives of the Bene Israel, who believe that after rising to heaven from a site near Haifa (in present-day Israel), he passed through India, where his chariot touched a rock in Khandala, a small village in Alibaug.

Chicken and mutton gravies made in Bene Israel homes are similar to the meat curries prepared in most Hindu households in the region, and fish remains a staple in their cuisine since many continue to live near coastal areas. Leora Pezarkar, a Jewish researcher who lives in Israel but is originally from Thane, shared that Indian threadfin (“dadha”) and Bombay duck (“bombil”), a fleshy eel-like fish abundant off the western coast of India, are the go-to comfort foods for the community. “I grew up eating it and love it so much; the fact that I can’t find Bombay duck in Israel is so disappointing,” Pezarkar said.

While Bene Israel cuisine is deeply syncretic, the community’s strict adherence to kosher rules has deeply influenced its cuisine, too. People buy only meat that is kosher slaughtered, the availability of which largely depends on access to ritual slaughterers. Dairy is not added to meat dishes and instead substituted with coconut milk, and milk-based Indian sweets like yogurt, ghee, butter and cheese are never served along with meat. In the absence of kosher wine in India, the Bene Israel learned to make a sherbet with black currants, said David, which are made for both Passover and the breaking of the Yom Kippur fast.

Indian Jews, she said, also make sure that their vessels for milk dishes and meat dishes are kept on separate shelves. Whenever they have roti or paratha (types of Indian flatbreads) with their curries, they do not add ghee on top of it, as is common in many parts of India.

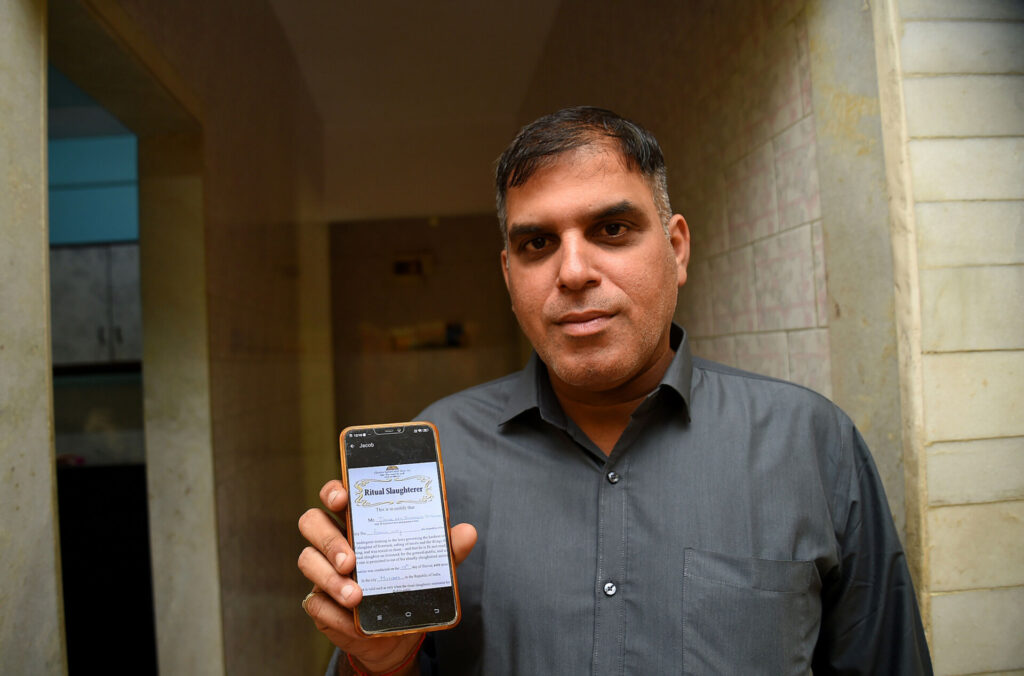

Jacob Varsulkar, Chandgavkar’s son-in-law — who is certified to carry out kosher slaughter and uses a knife that has come from Israel — is among the few ritual slaughterers in Thane. But in cities like Ahmedabad, where kosher meat is rarely available, most Bene Israel are vegetarians, said David. They instead have a variety of dairy-based foods and vegetables. Some staple dishes include fried eggs made in small steel bowls called katoris; sprouted flat beans sauteed with onions, tomatoes and spices; tilkut potatoes prepared with a special spice made of powdered sesame and red chili powder; and chauli, a curry made with black-eyed peas.

However, with the community decreasing as Indian Jews immigrate to Israel and other countries, their cuisine could be lost because knowledge about their traditional dishes has always been maintained through oral tradition, David said. While David uses storytelling to shed light on her community’s food heritage, Pezarkar started by dipping into her own family’s history to conduct online talks on the community’s foods and customs. Those like Chandgavkar diligently show up in the kitchen every day, sharing the food of their family with members of the community. She has also been catering to Indian-Jewish families across the globe since the early 1990s, selling her saandhans, halwas, dry chutneys and garam masalas to consumers in Israel and even the U.S., where a few Bene Israel have now moved.

Apart from food, in recent years in Alibaug, where the Bene Israel first settled, heritage walks and guided tours have brought renewed attention to the region’s Jewish past. The handful of Jewish families who stayed back in the villages do not shy away from talking about their history and welcome visitors into their now deserted synagogues, even as the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas, which began in October last year, has made them slightly wary, with many fearing they will become targets of misdirected anger.

India’s stand vis-a-vis Israel and Palestine has historically put the Indian-Jewish community in a difficult position. Whenever India responded strongly to any developments in the conflict, media attention would turn to the community. And while ties between India and Israel are said to be at a historic high with the Indian government tiptoeing around the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, Indian Jews, who have family in Israel, of whom a few are also on the battlefield, declined to comment on the issue with New Lines, citing the delicate nature of the subject.

At its zenith in the mid-20th century, Alibaug used to have over 250 Bene Israel families, said Pune-based researcher Pranav Vijaykumar Patil. But now the last remaining four families take care of the 19th-century Magen Aboth Synagogue on rotation. Prayer services are conducted once a month, even though they don’t have a cantor to lead. Otherwise, the synagogue sees high footfall only during tourist visits, which are rare and often restricted.

Almost all synagogues in and around the coastal belt of Raigad, the home of the Bene Israel before they migrated, are experiencing a similar fate.

“Raigad has several synagogues spread across villages — at one point there were at least 50 families in each village,” Patil said. “Now there are barely two or three families maintaining these synagogues.”

Shofeth Awaskar, 26, the youngest member of the Magen Aboth Synagogue, is tasked with carrying out the lighting of the lamps on Shabbat and other festivals. He also runs Shalom Inn, a guest house near the synagogue, where one can order a traditional Bene Israel meal, prepared by him and his mother. While many of his relatives now live in Israel, he calls Alibaug his home. “I’ve been to Israel before, but I like it in Alibaug for some reason. We’ve formed a relationship with the people living here,” he said.

Even in cities like Mumbai and Thane, which have the largest populations of Bene Israel today, businesses are being impacted by the dwindling numbers. Ritual slaughterer Varsulkar used to run India’s first kosher restaurant, Bityavno, in 2014, but he had to shut it down a few years later due to development projects in the area. His primary source of livelihood today is his catering business; he provides meals for pre-wedding functions of Bene Israel couples, such as the “mehendi” (henna) and “haldi” (turmeric) ceremonies adopted from Hindu wedding traditions, and wedding receptions. But this business, too, is experiencing a lull. “When I started off in 2011, I would cater for over 500 people. These days, we barely have a hundred guests. The number of wedding-related functions have also dropped drastically as many families have shifted to Israel.”

Meanwhile, families that left have been trying to maintain their roots. Apart from annual visits, they send donations for the upkeep of these synagogues. “The Bene Israel families living in Israel have also created a large community and are doing everything to preserve their link to Maharashtra and their native language, Marathi,” Patil said. They opened Marathi libraries and annually invite local artists to stage Marathi plays and performances. Until the pandemic, they also published Maayboli (“My Language”), a Marathi-language magazine that included short stories, songs, memoirs, heirloom recipes and matrimonial advertisements. There are also those like Chandgavkar’s sister, Mary Sassoon Bhonkar, who lives in Ashdod, Israel, and has been keeping the Bene Israel cuisine alive through her catering service.

Benjamin D. Waskar, a cantor at the Beth El Synagogue in Revdanda (close to Alibaug), owns an oil-press mill inherited from his forebears. Oil pressing used to be the traditional occupation of the Bene Israel living in the Konkan, earning them the sobriquet “Shaniwar Telis” (Saturday oil pressers), as they abstained from working on Shabbat.

As we walked into Waskar’s rustic yard, it was like entering a time warp. Surrounded by a grove of coconut trees on all sides, the air tasted of the salty sea, though the raucous whirring of the oil press machine drowned out the sound of waves. Perhaps this was how the Bene Israel once lived on the coast. In his quaint mill, littered with haystacks, straw baskets and tin boxes, Waskar worked through a mound of seeds from the Indian beech tree. The collected oil will be used as a coating on the fishing boats to prevent infestation by white ants.

Waskar lost his two young sons in a tragic accident last year and grief hung heavy in his home, but he continues to work to keep the Bene Israel tradition going.

“Parents send their sons to me, and I teach them the Torah and the prayers,” said Waskar, who is also a ritual slaughterer, providing meat to families living in the area. Our interview was cut short when a Jewish friend visited from Alibaug, requesting strips of wood. Waskar excused himself to help his friend in the workshop. As we prepared to leave, he insisted we have a hot cup of milk tea, reminding us that although those who remained in these villages may have endured losses of all kinds, food is not one of them.