When the song “Nasek Nasek” (Dance, dance) was released last year, it craftily spotlighted a minority community in Bangladesh. It featured a ballad in the Hajong language, which is spoken by an Indigenous ethnic group of about 80,000 people who reside in northern parts of Bangladesh (in Mymensingh and Sylhet) as well as by people living across the border in India. A song of celebration written and sung by Animes Roy in his native tongue, it opened the first season of Coke Studio Bangla last year, marking the debut of the popular musical show format in Bangladesh.

“The language is spoken by a minority. But when we were East Pakistan, we gave [our] blood for our language. If we don’t understand the need of cultural preservation then what was the point of the language movement?” Gousul Alam Shaon, managing director of Grey Dhakha, the creative producers of Coke Studio Bangla, told New Lines. He was referring to the “Bhasha Andolan,” or Language Movement, which emerged in the 1950s when Bangladesh was part of Pakistan and advocated for the recognition of Bangla (also known as Bengali) as an official language. As tensions escalated over two decades, it eventually led to the Liberation War in 1971 and the creation of Bangladesh.

This need to preserve the culture was further highlighted in another song, titled “Hey Samalo,” a rousing invocation sung by 15 people in unison, featuring famous lyrics from 1953 by the 20th-century Bangladeshi musician Abdul Latif: “Ora amar mukher bhasha” (They want to snatch away my mother tongue). The words were written to counter orders in 1948 by Pakistan’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah to make Urdu, the language of elite Muslims in northern India, the official language, even though Bangladesh (then called East Pakistan) is predominantly Bangla-speaking. Latif’s song documented the act of stealing one’s mother tongue; his stirring words upheld the resistance exhibited by people in the face of brutality. In the show, Latif’s song is paired with “Hey Samalo,” another protest song, penned by the Indian musician Salil Chowdhury during the Tebhaga peasant movement in an undivided Bengal in the last year of British colonial rule, 1946-47. Farmers were resisting their landlords for keeping two thirds of the grain they produced, advocating that the landlords take just one third instead.

Similarly, “Ekla Cholo Re” (Then walk alone), orchestrated as a musical triad, is borrowed from the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s famous song composed in 1905, during the Swadeshi (Self-sufficiency) movement, part of India’s struggle for independence. For the show’s use, it has been arranged in a medley with “Ami Kothay Pabo Tare” (Where shall I meet him), a song from the Baul tradition written by Gagan Harkara, a 19th-century Bangladeshi poet. The third song in the triad, the chorus, is taken from a love ballad called “Hashimukh” (Smiling face), composed by Shironamhin, a leading Bangladeshi rock band formed in 1996, which emerged from the underground music scene. The three songs are rooted in disparate milieus. One is Baul music, a type of folk song that unfolds as an admixture of Sufism and mysticism, popularized by minstrels from marginalized communities in Bengal. The second is a politically imbued anthem written for a specific event, while the third is a contemporary tune calibrated to modern emotions.

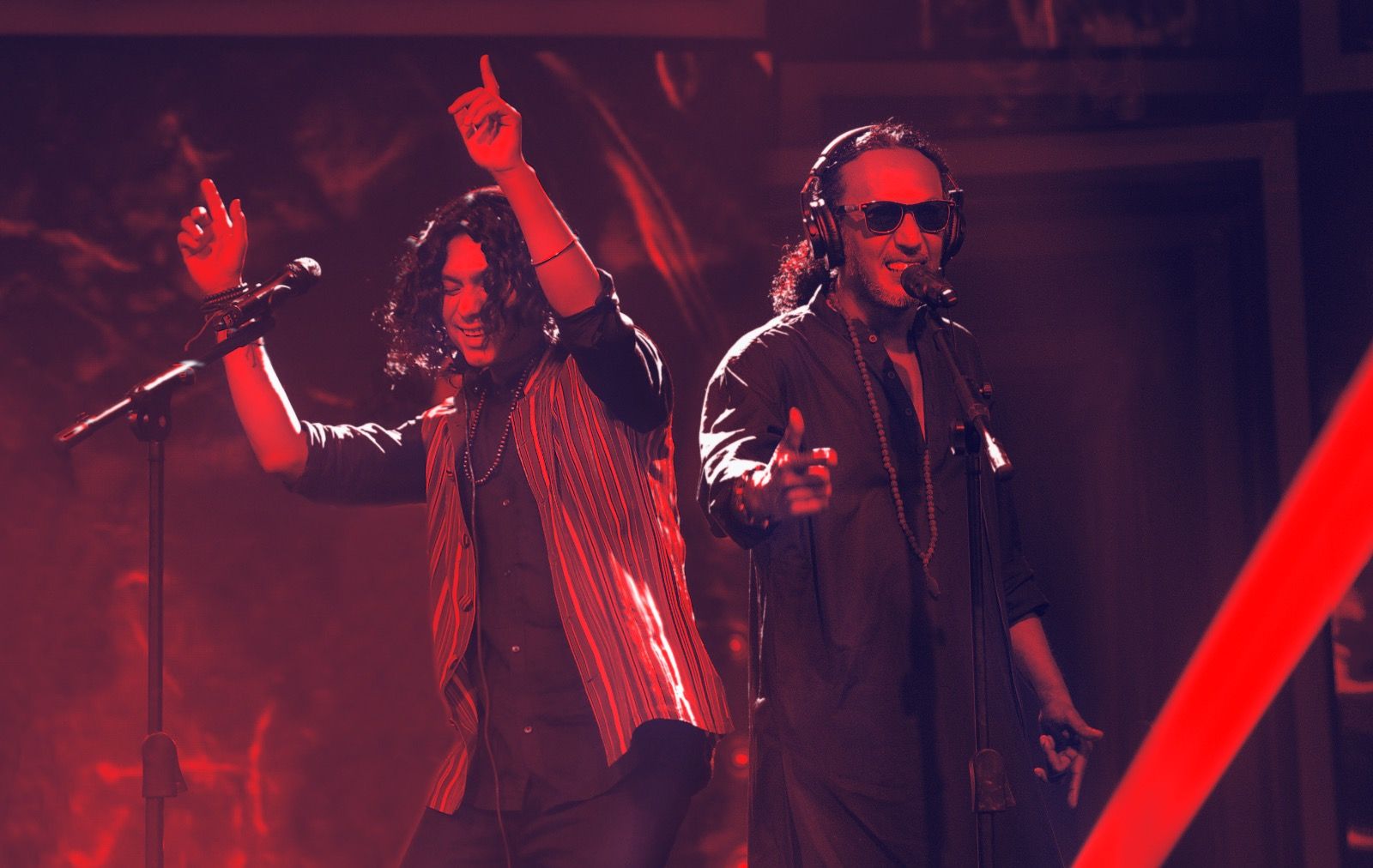

These collaborative renderings formed a thematic symmetry and set the foundation for Coke Studio Bangla’s creative first season, released on YouTube last year. The musical program returned with a second season this February. The first song of this season is an ode to a dilapidated public bus that was commonly found abandoned on the roads in Bangladesh in the 1980s. The rundown condition of the bus lent it a distinct place in the public consciousness and so it was given the sobriquet of “murir tin” (literally meaning an aluminum box filled with puffed rice) due to the potholes and rough patches on roads, which made it shake and rattle. The song was likewise named “Murir Tin,” which not only replicated the onomatopoetic imagery of the clanking sound of a worn-out vehicle but also evoked the chaos of riding a public bus. Sung by the Bangladeshi pop rock singer Riad Hasan, the song is interspersed with rap beats by artists from the cities of Khulna and Sylhet.

Backed by the global beverage brand, Coke Studio has been spotlighting diverse cultures and artists for over a decade. It originated in Brazil in 2008 as a one-off promotional project, but it was in Pakistan where it took flight. It was conceived first as a marketing strategy by Nadeem Zaman, then head of marketing at Coca-Cola in Pakistan, and aided by Rohail Hyatt, a trailblazer for rock music in the country. The project later emerged as a credible cultural platform and became a melting pot of musical genres, forms and styles indigenous to the country.

The idea was to impart a sense of identity through music for the youth of Pakistan during a crisis in 2006-7 due to terrorism and ethnic friction. This social project transformed Coke Studio Pakistan from an advertising gig to a watershed cultural moment. It has been an ongoing digital routine in Pakistan for 14 years, with each season featuring live-recorded performances of both established and emerging artists, making it the country’s longest-running musical show and creating a blueprint for the franchise. Over the years, Coke Studio has expanded into an international template with a similar ethos enveloping its subsequent iterations in Africa and the Philippines. In 2011, Coke Studio India was launched, though it ended four seasons later. It has now returned as Coke Studio Bharat, which will feature over 50 artists from across the country.

The premise of the franchise, which is to revitalize a musical heritage while acknowledging the strides of modernity, made for a unique cultural platform in South Asia, where countries are separated geographically but united by their common culture, customs and traditions.

“There is no doubt that, years ago, Coke Studio did begin as a marketing exercise for Coke. But the musical results from the show have been spectacular. It has put some brilliant musicians and a lot of the subcontinent’s significant yet ignored folk heritage under the spotlight,” Suanshu Khurana, a journalist and culture critic with The Indian Express, a daily newspaper based in India, told New Lines. Over the last 15 years, Coke Studio in South Asia has become a leading cultural platform where folk and traditional music combined with contemporary tunes and musical forms have thrived and been documented, and have retained several musical forms in pop culture, in turn becoming a case study for how corporate funding can help with cultural preservation.

India and Pakistan’s shared history and mutually hostile politics have lent a distinct legacy to Coke Studio. The fact that both nations were once a single entity not only tied in well with the program’s goal of inclusivity but also outlined myriad possibilities for collaboration. The Indian singer Shilpa Rao collaborated in the ninth season of Coke Studio Pakistan. Similarly, the Pakistani qawwali (a form of Sufi Islamic devotional singing) band Sabri Brothers united with the Indian singer KK in the first season of Coke Studio India.

Yet the absence of Bangladesh from the franchise was conspicuous, given that the country shares a history with both India and Pakistan. During the 1947 Partition, the Muslim-majority states of Punjab and Bengal in British India were divided to form Pakistan. Later, in 1971, the fragment of Bengal which had become East Pakistan attained independence as Bangladesh.

The Bangladeshi lyricist and scriptwriter Gousul Alam Shaon had been pushing for the Coke studio “asset” for some time. “But the brand needed to be convinced,” he said. In the latter half of 2020, the brand approached Grey Dhaka, an advertising agency, to launch the country’s version of the musical set. Shaon, who serves as the agency’s creative chief, said, “It is not an easy thing to commit [to]. We knew how huge this was because it had to be done in a certain way.” However, by early 2021, plans were formalized. Shaon wanted Shayan Chowdhury Arnob, an acclaimed Bangladeshi singer whose fame has spread across the Indian border, to head the enterprise.

Instead of the standard model of naming a Coke Studio production after the country, Shaon wanted theirs to be named after their national language, Bangla, which is spoken on both sides of the Indian-Bangladeshi border. True to this goal, the songs of the first season were firmly rooted in the vagaries of the Bangla language, the fifth-most-spoken language in the world. In Bangladesh, the dialects of the language shift with every region. For example, residents of Chattogram, the second-largest city in the country, speak in a different tone to those in Sylhet, in the northeast.

In keeping with the Coke Studio format of fusing the traditional with the contemporary, the song “Bhober Pagol” (an affirmation of the frenzy that resides in all of us, because the word “pagol” means a “mad person” in Bangla) blends two distinct genres. Nigar Sultana Sumi, an established singer in Bangladesh, lends her voice to a popular folk song “Pagol Chara Duniya Chole Na” (The world does not run without crazy people), which is combined with an original hip-hop piece furnished by Jalali Set, a group of four Bangla rappers. The differing beats of the songs make way for each other through the unique sound of the ektara (a one-stringed musical instrument used in the traditional music of South Asia), which is featured alongside the electric guitar and alto saxophone.

This playful inventiveness aligns with the format set by the Pakistani counterpart. But Bangladesh’s insistence on designing an entire season resulted in a rare creative feat. “That was our call,” said Arnob. He himself was involved in the landscape of independent music, having formed a fusion band called “Bangla” in 1999. Although it’s been inactive since the late 2000s, the “Bangla” band was preoccupied with revamping folk songs for the youth. Now, years later, the 45-year-old singer is heading up something similar. At first, the Coke Studio team and the singer spent two months just brainstorming ideas. “We had drawn up an exhaustive list of nearly 200 songs. From there we selected songs on the basis of musical potential,” said Arnob.

For Shaon, this is an effort to reclaim different aspects of their culture. “We are not just going to do a Tagore [the Bengali polymath] cover and send a message that we don’t associate with rock bands. Instead, we are saying, everything is ours. Baul is ours, Tagore is ours and so is the band culture,” he explains. The experiment is also the living, breathing result of a nation utilizing the potential of such a platform and stacking it to the limit with everything they have to offer. The sheer diversity on display in the first season is worth the price of admission alone.

With its use of 11 songs, Coke Studio Bangla mines the contributions of culture-shapers in the nation. There are songs written by Kazi Nazrul Islam, the national poet of the country, and Tagore, who penned Bangladesh’s national anthem, “Amar Shonar Bangla” (My golden Bengal). There is a melody by Sachin Dev Burman, a famous music director in India, who was born in Comilla, in present-day Bangladesh. He made the musical styles of Bangladesh mainstream in Hindi films. Apart from being part of “Ekla Cholo Re,” “Hey Samalo” and “Bhinnotar Utshob” (Festival of diversity), for his duet performance, Arnob reprised his “Chiltey Roud” (Sliver of sunshine) — a contemporary rendition of yearning — from his 2005 debut album “Chaina Bhabish,” which can be loosely translated as “Don’t want you to think about me.”

Yet a culture is not just its people: It is also traditions that have withstood the test of time. Shaon and Arnob’s reckoning is reflected in the thoughtful incorporation of folk songs, rooted in the sociopolitical history of Bangladesh and passed down orally through the generations. The first season includes various folk traditions from different parts of the country, such as Bhawaiya, a form of folk music popularized in northern Bengal that evokes a sense of melancholy. Another example is Maizbhandari, a spiritual genre of folk songs with origins in the Chattogram region; and even Bhatiyali, contemplative music of the riverine subcontinent, which evokes the pathos of fishermen. Along with those examples, there are dynamic tunes by contemporary bands such as Shironamhin and Jalali Set.

Coke Studio Bangla is a compelling production by musicians prioritizing the need to showcase their language. Pradyut Chatterjea, a musician from the state of West Bengal, India, and a longtime collaborator with Arnob, finds it fascinating. “Bangladesh’s fight for language is like no other. They launched their season with a song in [the] Hajong language. We don’t have the courage to do it, we are scared,” he told New Lines. Chatterjea played the piano and synthesizer in the first season.

Such commitment is not just emotionally driven but also politically charged. Language, after all, was the raison d’etre of Bangladesh’s freedom movement. “Our freedom fight was more of a cultural movement than just a war,” Shaon says, harking back to the singularity of their struggle.

Unlike India, Bangladesh sought liberation from an autocratic government, not a foreign invader. It moved out of Pakistan to assert cultural autonomy and challenge religious hegemony. In the late 19th century, when India was still colonized, Bengal registered a marginally higher Muslim population, most of whom resided on the eastern and northern sides. When the All-India Muslim League — the political party devoted to safeguarding the interests of the Muslims on the Indian subcontinent — proposed a separate nation of Muslims, many living in East Bengal supported it. “Pakistan in East Bengal was a way for Muslims (many in the East being subordinate to, and discriminated against by Hindus) to gain dignity; aspire to education, jobs and prosperity in a new system after the end of colonial rule,” Dr. Neilesh Bose, Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair at the University of Victoria told New Lines.

The reality, however, turned out to be different. East Bengal, including Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and other communities, became East Pakistan, ethnically homogeneous and speaking one language — Bangla. West Pakistan (now known simply as Pakistan) was a disunified cluster comprising West Punjab, North West Frontier, Sindh and Balochistan. Soon after 1947, West Pakistan started discriminating against East Pakistan, using language as the means. “Bengali members of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan were not allowed to address the forum in their mother tongue,” writes Abu Saeed Zahurul Haque in “The Use of Folklore in Nationalist Movements and Liberation Struggles: A Case Study of Bangladesh.”

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, only further exacerbated the divide by proclaiming on March 21, 1948, that Urdu would be the national language. This planted the seed for resistance among the Bengalis, resulting in the 1952 Language Movement, during which police opened fire on students at Dhaka University on Feb. 21, 1952, who were demonstrating to demand recognition of Bangla as one of the official languages of Pakistan. The day has been lodged in the social lexicon as Ekushey (“21” in Bangla), remembering the struggle and sacrifice of the people. In 1999, UNESCO announced that Feb. 21 would be observed as International Mother Language Day worldwide. (Poignantly, both seasons of Coke Studio Bangla were launched in the month of February as a tribute to that moment.)

Until 1971, when East Pakistan mobilized to fight its war of liberation, power remained concentrated in the hands of West Pakistan, manifested by one military oligarchy after another. In fact, the nine-month-long Liberation War was fuelled by the West Pakistani troops’ attacks on the people of East Pakistan, including the rape of women and the killing of thousands. In the midst of all this, East Pakistan revealed its intent by offering support for the politician Sheikh Mujibur Rahman — known as the founding father of Bangladesh — who spearheaded the secular political party All Pakistan Awami Muslim League. On Dec. 16, 1971, East Pakistan finally emerged victorious over the West Pakistan army, aided by India.

During the liberation fight, music played a crucial role in spreading the fervor of fighting for one’s language. A radio broadcasting center called Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra was established by the government of Bangladesh, playing patriotic songs and lending rousing support to the spirit of the people. Coke Studio Bangla is an ode to this struggle. Everything from the choice of songs to the artists they choose to showcase is intended to highlight their pride in their language and the blood they shed to be able to speak their mother tongue. The inclusion of Tagore, Islam and Chowdhury is not incidental.

The subtext for Bangladesh’s fight for language was an assertion of secularism. It was a declaration that any country that houses people with different beliefs cannot be stifled by the garb of one religion. This became crucial because, over the years, Bangladesh has struggled with religious extremism. The 1972 constitution referred to the country as a secular nation-state, but Islam was made the state religion in 1988 under Hussain Muhammad Ershad, a former president of the country and a military dictator. An amendment in 2011, however, restored secularism as a fundamental constitutional principle.

Against this backdrop, the song “Prarthona” (“Prayer”) not only reiterates the secular politics of the nation but reveals the redundancy of conflating religion with faith. Arranged as an appeal to a higher force and sung by the Bangladeshi artists Momotaz Begum and Mizan Rehman, it is a confluence of two pieces. Begum croons “Allah Megh De” (“O god, give us cloud”), a folk song embedded in the Indian subcontinent’s history of famines, written by the Bangladeshi composer Girin Chakraborty. Rehman joins her midway with his invocation to “Baba Maulana,” a famous composition by Kobial Ramesh Shil, a Chattogram-born poet who challenged social oppression all his life. Interestingly, while both songs have been credited to Hindu artists, they are steeped in Islamic imagery (the genesis of “All Megh De” can be traced back to the legend of the Battle of Karbala, in which the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, Hussein ibn Ali, was killed; the supplication for rain evokes the thirst faced by Hussein’s followers during the battle).

This religious introspection transitions to caste contemplation in “Shob Lokey Koy.” The song brims with the idea of fairness, summoning us to view the world beyond restrictive barriers. Designed as a medley, the companion pieces — one by the 19th-century, Bangladesh-born poet Lalon Fakir, one of the most influential advocates of Baul philosophy of equality, and the other by the 15th-century Indian poet Kabir Das, born in Varanasi, India — are sung by the Bangladeshi singer Kaniz Khandaker Mitu and the Indian singer Soumyadeep Sikdar, who goes by the moniker Murshidabadi. This convergence of artists from two different Bengals mirrors the unified belief of the original creators of the songs, despite the temporal gap between them.

The songs do not simply egg us on to reimagine a world where music is a solution to divisiveness. Instead, they entreat us to confront an increasingly divisive world, while upholding the cost of freedom and the price of fanaticism. “The first season noiselessly journeys through issues of caste and identity politics, making it a spectacular space in a polarized world. What makes it significant is that in a post-liberalized Bangladesh, now a space where multiple cultures continue to merge, it is presenting ideas that otherwise seem at odds with each other, especially in nations like India and Pakistan. Lalon meets Kabir and the message — rejection of social inequalities — is relevant for everyone,” says Khurana.

Harmony and acceptance have been the overarching intent since inception. “These songs emphasize who you are because in this age of globalization, we are living in a seemingly borderless world which has barbs all around. We had to find a way to underline the need for inclusivity when the institutions around the globe are thinking otherwise,” said Shaon.

This is the brief Arnob worked on as he dressed each classic with a modern twist, creating a mixtape for the youth. In “Lilabali,” a wedding song by the Bangladeshi poet Radharaman Dutta, the archaic bridal musical instrument called the shehnai is effortlessly accompanied by a saxophone. In “Bulbuli,” a Nazrul song is presented with Latin beats. Electric guitar, drums and percussion are flamboyantly used in folk songs, transforming them into modern entities without robbing them of their basic core.

It is chaotic but it fits. “Coke Studio Bangla has recorded the highest number of incremental users in the overall Coke Studio franchise,” Arnab Roy, vice president of marketing at Coca-Cola India and SouthWest Asia, told New Lines. This success has resulted in the initiation of another language-based edition of the franchise: Coke Studio Tamil was launched earlier in January.

To the musicians back home, it has given hope. “The musical industry in Bangladesh is struggling. There is no royalty, little streaming and few ways to monetize it,” Arnob laments. The popularity of the first season has come at an interesting time. It may be no overreach to assume that Bangladesh, at this moment, is going through a cultural resurgence of sorts. In 2021, the Bangladeshi filmmaker Abdullah Mohammad Saad’s film “Rehana Maryam Noor” was selected in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival. Last year, Nuhash Humayun’s short “Moshari,” a horror film on climate change, won the prestigious Grand Jury Award at SXSW 2022 and became the first Bangladeshi film to qualify for the Oscars. The success culminated in Oscar winners Jordan Peele and Riz Ahmed coming on board to back the film as executive producers.

In his interviews regarding Coke Studio Bangla, Arnob uses an abiding example. “Look at the K-pop industry. They have built an empire from scratch,” he says. He repeats this analogy, adding that it was time to cater to young people. If the breathless comments underlining each video are any proof, he is on his way to doing something similar. Place is no barrier. This season has two singers from India, Madhubanti Bagchi and Soumyadeep Murshidabadi. Arnob himself has spent 17 years studying in Visva Bharati University, a unique educational institution in West Bengal’s Shantiniketan, founded and developed by the Tagore family. Alluding to that part of his life, the singer says he considers both parts of Bengal his own. Language, after all, has the distinct capacity to evoke a sense of home.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.