The modest town of Badami, in the South Indian state of Karnataka, appears a bit dusty and worn. Eateries and cheap clothing shops line the streets; an unassuming dairy shop boasts of delightfully creamy lassi — a traditional yogurt-based smoothie-like drink common in South Asia. I strolled down the uneven pavement with my climbing companions in search of dosas and idlis — traditional pancakes and rice cakes made in southern India — to fuel our adventures for the day. Monkeys roamed the fringes of the town. I was warned to keep all food sealed tight to avert mischief.

Formerly known as Vatapi (meaning “having the wind as an ally” in Sanskrit), Badami was once the regal capital of the Chalukyas, a dynasty that ruled major portions of southern and central India between the seventh and 12th centuries. Considered a cradle of temple architecture in the region, Badami has been a destination frequented by religious sojourners for centuries, where people have brought their families to marvel at the shrines and pay their respects.

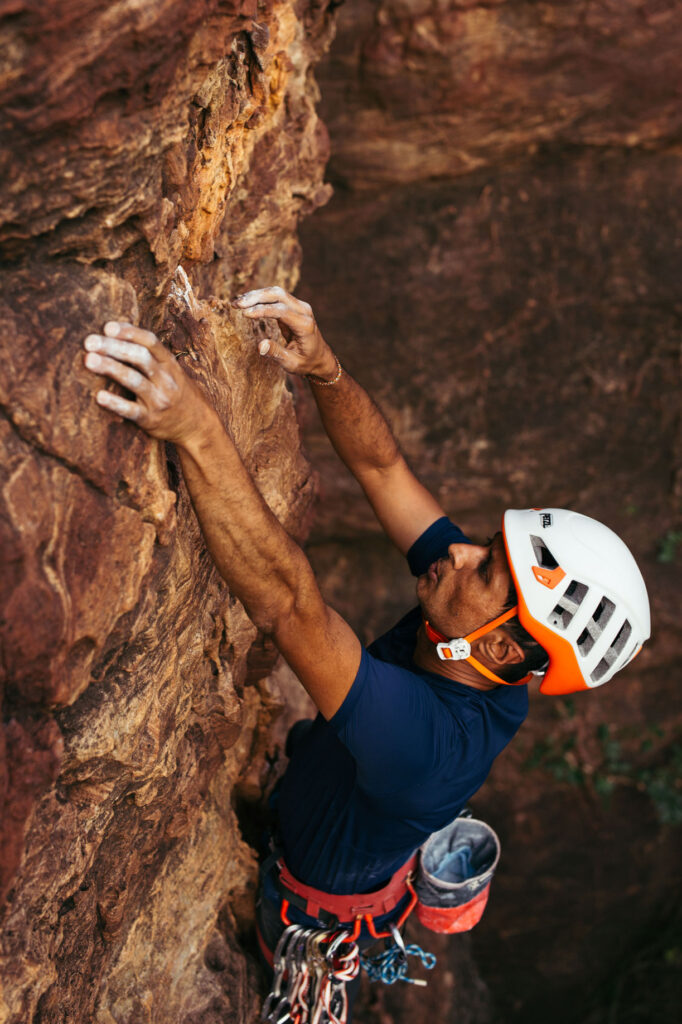

For decades, Badami was a foreign climbers’ haunt; they developed routes at the sunset-colored gorge in the 1990s. India’s hardest sport climbing route, the Ganesh crag, is in Badami. It was first ascended by the French world champion, Gerome Pouvreau, in 2013. This feat was soon repeated by the 22-year-old Tuhin Satarkar, the first Indian climber to do so, which helped garner international respect and momentum for the town. It’s now considered to be India’s sport climbing mecca. Among its long-revered rock-cut temples, a second wave of rock climbing activity is now developing — this time led by local climbers.

With its magnificent hill ranges such as the Western Ghats and Aravalli, India has long captivated thrill-seekers. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that rock climbing gained traction, catalyzed by British climbers. Their access to resources allowed them to invest in gear and time to scout out crags (rock climbing areas). Soon after, French, American and other climbers from the West flocked eastward, continuing the expansion of climbing areas across India. Meanwhile, the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, established in 1954, began advocating for rock climbing to bolster the Indian army’s mountaineering capacity.

While the northern states may have some of India’s hardest climbing areas in terms of altitude and exposures — such as the granite in Ladakh, the Kashmir region or the sandstone of Ramjas by New Delhi — Karnataka in the south is developing its own claim to the sport. Its capital, Bangalore, boasts some of the best climbing opportunities in the country, according to Sohan Pavuluri, the founder of Bangalore Climbing Initiative (BCI).

It’s hard to say exactly why climbing has taken off in Bangalore. Locals have been exploring their natural rock surroundings for years via scrambling, hiking or bouldering. But it wasn’t until the 1980s that the most modern form of the sport was popularized. Climbers like Govind Raju and Usha Ramaiah were early pioneers, who respectively founded the Deccan Mountaineering Club and the Karnataka Mountaineering Association, and the sport was nudged forward as difficult-to-source equipment was acquired for members to share. “The ’80s and ’90s were the golden years of climbing in Bangalore,” Pavuluri explained. “People established long 300-, 400-meter routes from the ground-up culture — they’re brilliant,” he said, referring to routes ascended only from the bottom up, with high possibilities of falling, and not practiced on a rope attached to the top of the climb.

Documentation of the earliest climbs is hazy, said Pavuluri, who has been blogging about India’s climbing history for many years now. Ibrahim Farm, an area about 34 miles from Bangalore, has some of the best early documentation from that era, driven in part by competitive athletes who wanted to see who was climbing the hardest or most interesting routes.

Before the sport gained a fervent following, Indian climbers competing at the international level faced a host of challenges, ranging from lack of sponsorship and difficulty in acquiring gear to a confusing conflation of rock climbing with hiking. “People would sign up for a climbing session, thinking it was hiking, and be confused when we start taking out the ropes and harnesses,” said 27-year-old Jerry Vikram, a professional climber and guide in Hampi, a world-famous bouldering spot about 90 miles southeast of Badami.

Although Vikram was climbing some of the hardest grades in India by his late teens, he never managed to obtain the sponsorship required to make it as a professional athlete. He described how he and fellow Indian climbers felt “unseen” by the international climbing world despite their achievements. Nevertheless, a steadily rising number of Indian climbers have been undeterred.

Ravi Waddar, 22, is one of them. A Badami native, he first tried climbing in 2016, believing it could help with physical conditioning since he was a hammer thrower on his school’s track and field team. But when he traveled to Bangalore for a climbing competition with a few friends, he caught the eye of climbing coach Praveen C.M. A champion in his own right, Praveen consecutively won 14 of India’s national climbing competitions and is now committed to training young athletes from marginalized communities. He noticed Waddar’s strength, fearlessness and natural movement, and took him under his wing, supplying him with coaching, along with shoes and some gear. At present, Waddar is working on the Ganesh crag. “I have all the moves,” he said. “I’m just working on connecting them.”

But as instructive as these years of training with Praveen were, Waddar also saw just how much the odds were against him. The lack of opportunities in rural places is a major hindrance. He fills in as a manual day laborer when work is available; he’s also responsible for caring for his aging parents and younger siblings. “It’s not possible for me to work and help out with my family, and make it as a real climber at the same time,” he said.

Despite the disappointments of competitive climbing, Waddar believes that the intrinsic togetherness of the sport makes a difference. He loves it because “having it helps you make the person you are.”

“Climbing in Badami is still at a very nascent stage,” said Satish Venkatachaliah, a former professional climber, who first began climbing in the 1990s, as part of KMA. He soon started competing in national competitions in Mysore, Delhi and Kolkata, and even participated at the first X Games Asia in Thailand in 1998, which focuses on extreme sports.

Before bolting — climbing with fixed anchors — took off in Badami, making it a center of sports climbing, the town used to be a haven for trad climbing, a form of freestyle climbing where the lead climber places nuts, cams and hexes into natural cracks and slots and the following climber removes them. “For some strange reason, we always believed that this was a trad place — although now it has phenomenal sport climbing,” explained Venkatachaliah. Indian climbers learned how to bolt routes themselves, which has opened up access to others, making Badami a site for climbing camps that prepare youngsters for national climbing competitions.

While the rise of climbing in Badami might be a palpable benefit to local businesses, namely hotels and restaurants, the process has not been without tension. Some locals are apprehensive of foreigners coming in to enjoy the climbing yet lacking respect or knowledge of Badami’s cultural and heritage significance, said Venkatachaliah. Climbers also have a reputation for being “dirtbaggers” who don’t spend a lot of money — perhaps even coming to Badami because of how far $10 can get you in a day.

Over 280 miles south of Badami, in the concrete metropolis and global IT hub that is Bangalore, the climbing scene is almost purely community-driven. For instance, BCI, initiated by Pavuluri, has been the source of many friendships forged in the last decade. BCI hosts bi-monthly workshops and helps develop new climbing routes across Karnataka. These days, the community is growing faster than Pavuluri can keep up with. He credits much of the sport’s popularity to social media. “People will travel from all over India to learn how to trad climb here,” he said.

Yet as with many emerging climbing scenes, gear access remains a challenge. India, despite its remarkable manufacturing prowess, still has yet to produce its own climbing gear. In the 1980s, the prohibitively high cost of technical gear (e.g., pitons, ropes and harnesses) was a major contributing factor to the lag in Indian participation in the sport; climbing shoes with the necessary sticky rubber could easily cost an average civilian’s monthly salary. “It’s still an elitist sport because of that,” said Pavuluri.

For Amith Bangalore Vijayakumar (known as BV), a 27-year-old graphic designer and Bangalore native named after his provenance, finding a community in the city has been hard. “It is a huge, rapidly growing international city, where the population moves in and out,” he said. But BCI helped him find a near-instant community, with whom he embarks on weekend climbing adventures.

I started climbing three years ago in Nairobi, Kenya. Last year I heard an interview on The Enormocast, a climbing podcast, with Gowri Varanashi, the founder of Climb Like a Woman. Through her story, I connected with the BCI community on a trip to India. On my first day in the country, BV and I drove to Ramanagara, about 30 miles from Bangalore, to climb over a constellation of 10 or so crags. Ramanagara has been experiencing an interesting streak of second-wave development, as local climbers mule in gear and equipment from overseas.

Parking along one of the many lush, nondescript villages, we headed toward a section of the crag called Sentapi, passing by fertile cropland and several curious children. I led a few slab routes (climbing at angles less than 90 degrees that you lean onto, which requires balance and precise foot placement), and relished the views from the bolted anchors at the top of the routes. Gazing over the tesselating croplands and even more mountains, the potential for new routes here seemed boundless.

A week later, I met up with a dozen climbers in Badami. Many of them had just gotten off the nine-hour train ride from Bangalore and were already on the walls. Members of an informal group called the Badami Monthly Pilgrims, they meet every month for a solid weekend of climbing.

Climbers generally adopt a “leave no trace” principle geared toward conservation and respect for the natural rock and its environs. “Climbing visitors generally have a much, much lower impact on Badami, as opposed to other religious or heritage tourists,” said Amit Maniroth, one of the climbers from Bangalore. Concerns have still been raised regarding climbers’ impact on the rock. “There are routes on a wall a little beyond the cave temples, but no one is allowed to climb there now,” he continued. “The Archaeological Survey of India, which manages heritage sites, didn’t want climbing that close to the cave temples.” But as long as climbers uphold their end of the unspoken bargain by being on good behavior, the authorities seem okay with climbing in northern Karnataka.

Varanashi has had more intense interactions with the authorities. An avid route-setter, she has run into issues with forest officers outside Bangalore who claimed that she and friends were trespassing. Officers have minimal exposure to the sport and tend to associate those in the outdoors with some kind of illicit activity, she said.

Narayan Pai, a Bangalore-based climber, along with other climbers, runners and cyclists, has also met multiple times with forest authorities, who he explained treat climbing as a liability. “They’re concerned with safety precautions, and worried about being blamed by high authorities if something were to happen,” he said. For instance, in late 2019 Turahalli — a popular bouldering area on the outskirts of Bangalore city — was shut down indefinitely. Pai said that initially authorities had even wanted to make the area into a park, “But now it’s deserted.”

As dusk settled in, fireworks started bursting suddenly overhead in the lavender sky. “It’s Jatre,” BV explained — an annual festival in which Hindu pilgrims trek to famous temples in Badami, like the Raghunath Mandir, a 19th-century temple dedicated to Lord Rama. As we were packing to leave, beautifully dressed families streamed in, carrying garlands of marigolds and baskets of coconuts to offer at the temple. Such were the different energies pulsing through this place: an ancient energy emanating from centuries’ worth of religious duty, now blending with something new — a still-nascent climbing community’s eagerness to relish Badami for its rock.