In an age defined by disinformation, it has become almost a cliche to talk about “post-truth politics.” But while truth has been the media’s foremost concern in the era of “fake news,” there has been surprisingly little reflection on what it actually means in the first place. We’re exhorted to defend it from authoritarian leaders and conspiracy theorists alike, yet we seldom consider what precisely it is that we’re defending. But Sophia Rosenfeld, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania, certainly has. In her book “Democracy and Truth: A Short History,” she asks whether democracy really does require the truth to function — and what that even means.

“Truth is definitely a slippery idea,” she tells New Lines’ Faisal Al Yafai. “The way truth works, especially in democratic settings, is that we don’t authorize any one person, or one institution, or even one method, say, as the way to know something. That is wonderful in certain ways. But of course, it also makes knowing anything very messy.”

The relationship between modern democracy and truth goes all the way back to the 18th century. The knowledge of intellectual elites, the thinking went, would be balanced by the common sense of the masses. Consequently, explains Rosenfeld, the truth has been up for debate ever since — “I don’t think we lived in some sort of golden age of truth where everybody agreed about everything and then suddenly we fell off a cliff.”

“We’re catching up with a phenomenon that we didn’t know we were unleashing when we did.”

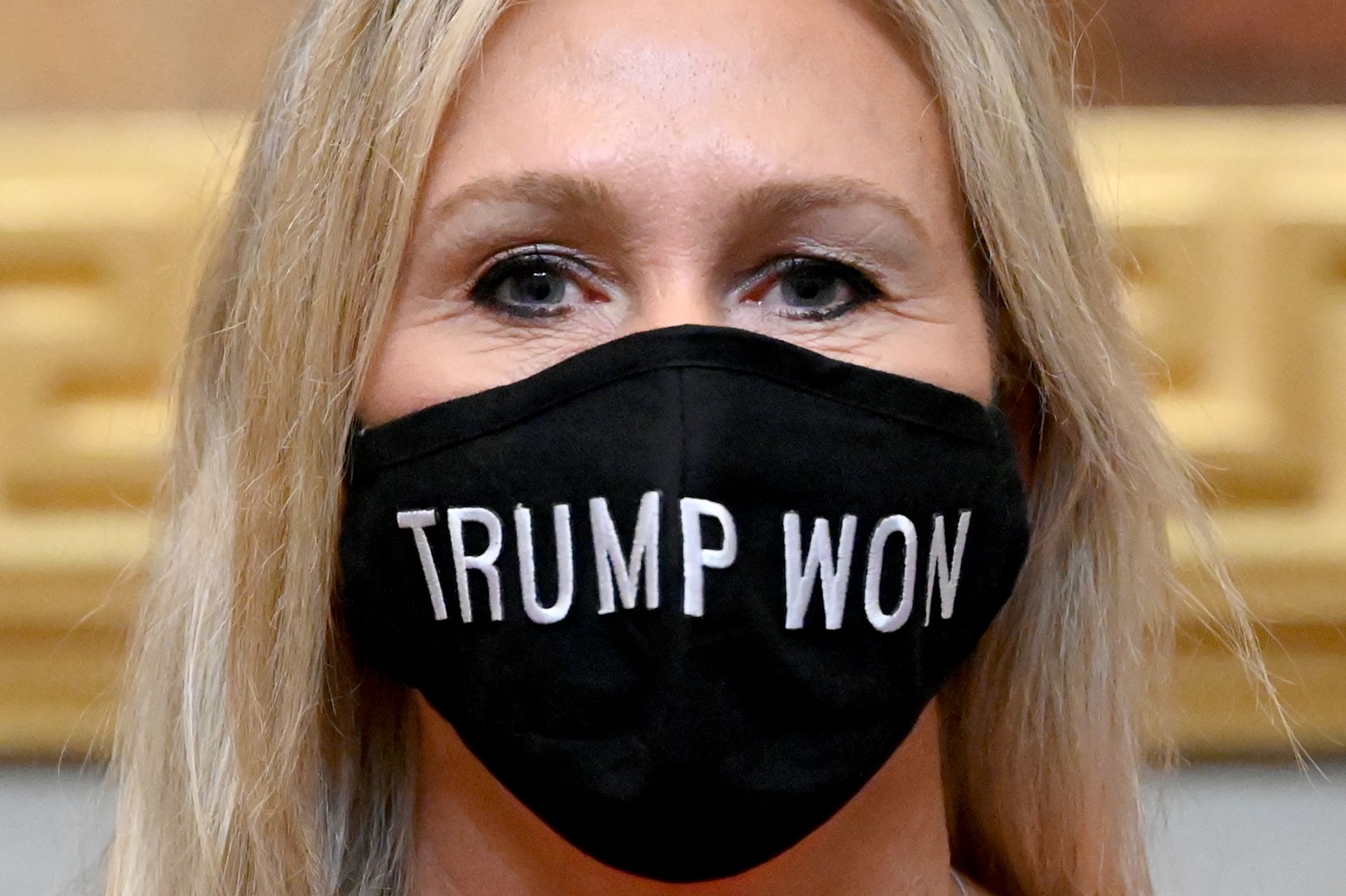

But while the truth may never have been as certain as many like to imagine, today’s degree of polarization nevertheless poses a new and dire challenge.“To have a good debate, we have to first agree that there’s a problem,” says Rosenfeld. “If we can’t even agree on something like the unemployment rate, democracy starts to fall apart.”

Rosenfeld is reluctant to ascribe a single cause to the current epistemic crisis. But social media and the internet, she argues, have contributed to it, especially in the absence of effective oversight. “When we have a technology that can spread lies so quickly and so far, and when we have a legal system that has basically let media companies operate without much regulation, there is a kind of open door to falsehood.”

“The law doesn’t help us much here,” she adds. “The technology doesn’t help us much here. We’re catching up with a phenomenon that we didn’t know we were unleashing when we did.”

Produced by Joshua Martin