Hosted by Surbhi Gupta

Featuring Shruti Kapila

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

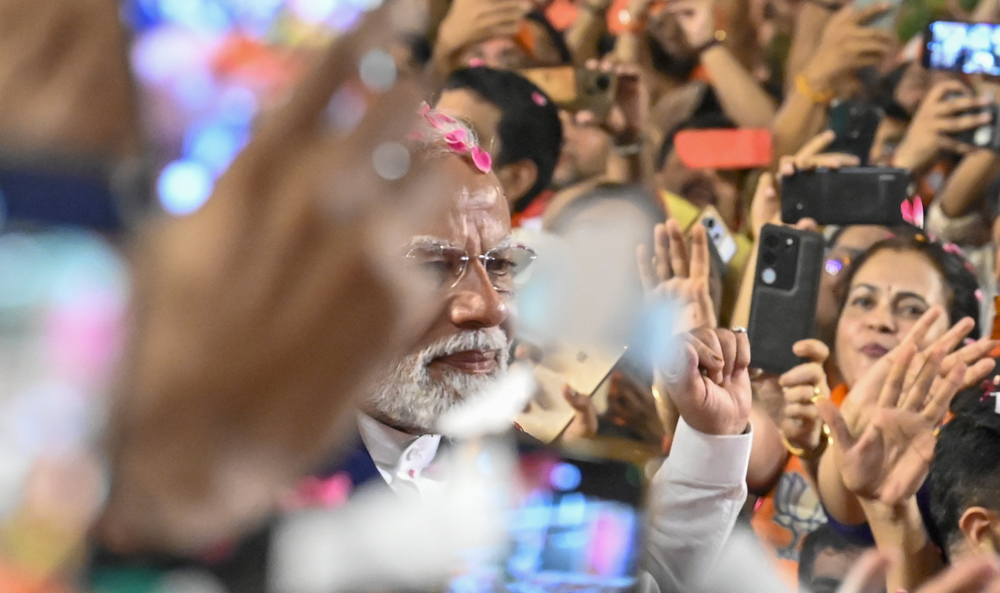

The surprise Indian election result earlier this month upended the established consensus on Indian politics that had been crafted not least by incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself.

“There was this kind of inevitability written by not just exit polls, not just the mainstream media, but very much the way Modi himself has fashioned his rule,” Shruti Kapila, author of “Violent Fraternity: Indian Political Thought in the Global Age,” tells New Lines’ Surbhi Gupta on The Lede.

“India remains instructive for global democracy, because in a way I would say that the age of populism has come to an end.”

Modi’s failure to win his party a simple majority in parliament, explains Kapila, “was a shocker of a result because his own slogan of ‘400-plus’ was also asking for a two-thirds majority of the Indian Parliament.” The number, she explains, reflected Modi’s ambition and intention to win the necessary majority to make major changes to the Indian constitution.

The result, says Kapila, “has broken the spell of Modi as infallible. … His power is very fragile, even though he remains prime minister.”

Before Modi, coalition governments had been commonplace in India for the previous three decades, but the strongman prime minister had enjoyed majorities in parliament since coming to power in 2014. Now, for the first time, Modi will have to learn coalition politics, explains Kapila. “He’s been forced to play and behave like any other Indian politician. He’s been cut to size because he’s now going to have to sit at the table and negotiate with other partners who will demand things in return for their support,” she says.

“The checks and balances, which were expected from other organs of government, and which have been nearly absent in the last 10 years … will now be given by the political stakeholders who are sitting with [Modi] in government,” Kapila adds.

The defeat of Modi’s party in the same state where he had erected a hugely controversial Hindu temple speaks to a wider lack of support for his Hindu nationalist project, says Kapila. “The project came undone,” she says. “I’m not saying it’s finished. I just think it has absolutely dented and thwarted the inevitability of a Hindu-first India that many were expecting. … The Indian electorate have really given Modi the biggest shock in this election.”

Kapila sees a major strength of the resurgent opposition in its ability to offer new language and ideas to counter right-wing populism. “I think there’s a new kind of vocabulary emerging, a new political grammar emerging, which is not simply socialism, it’s not simply populism, it’s not simply progressive populism,” she says.

The opposition Congress party, once again at the forefront of Indian politics, “has done something I had not expected it to do, which was to use its loss of power to discover its core principles.”

The takeaway from this election, says Kapila, is that “India remains instructive for global democracy, because in a way I would say that the age of populism has come to an end.”

Further listening:

The War on India’s Free Press — With Manisha Pande and Samar Halarnkar

India’s Political Hinduism — With Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay

Further reading:

Why the Indian Election Results Present Modi With a Defeat Within a Win

The Recent Elections Demonstrate India’s Growing Democratic Deficit