Colonial rule left Kenya almost as suddenly as it arrived. The colony gained independence in 1963, seven decades after the British first declared it a protectorate. In Kericho, however, time has stood still — suspended in a dark and torturous past.

Bright green emanates from fields across the Kericho district in Kenya’s Rift Valley, as sprawling tea estates carpet the soil. Along the edges of the long rows of leafy theaceae plants are small, red-roofed homes built during British rule that once housed the African workers of the colonial tea plantations. Today, workers employed by multinational tea companies live here.

Along the streets in Kericho town, young men and women knock on car windows. With wide smiles, they hawk the world-famous Kericho Gold tea. A refreshing gust of wind sets the rows of burgeoning tea plants shaking and dancing as it glides past them across the fields.

These tea estates, some of which still bear their traditional Kipsigis place-names, have also attracted tourists to Kericho, who book hotels advertising their proximity to this tea-growing landscape.

But, for 95-year-old Tito Arap Mitei, these charming and lush tea plantations are a constant reminder of a painful past, when in the 1930s the British violently evicted him and the rest of the native Kipsigis to make room for themselves.

“Whenever I see my land, I feel something burning inside my stomach,” he says. “I feel so much anger because what these people did to us is not right.”

Like thousands of others, Mitei watched, teary-eyed, over the decades, as the forests and trees, some of which marked the graves of his ancestors, were torn down and cleared for the creation of these tea estates. Technology progressed. Large plows replaced the African workers. Flinging dirt into the air, they tilled the lands while unearthing the bones of his ancestors — an act forbidden in the Kipsigis culture.

Although cheers of “uhuru” (freedom, in Swahili) rang out across the country on the eve of independence, the Kipsigis’ lives would be little changed. Colonial tea farms grew into multinational corporations, and the Kipsigis remained landless.

For decades, displaced Kipsigis have been waiting for the Europeans to leave, so they can return to their lands and heal from the colonial abuses they endured, which ripped apart a once-powerful tribe.

Their patience, however, is quickly running out.

The Kipsigis are the largest subgroup of the Kalenjin, who migrated to the Rift Valley of present-day Kenya hundreds of years ago. More than a century ago, the Talai clan became leaders of the Kipsigis, owing to the belief that they harbor supernatural powers that allow them to communicate directly with “Asis” (God, in the Kalenjin languages).

On June 15, 1895, the lands of present-day Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda were declared a British protectorate and would be referred to thereafter as British East Africa. Kenya did not officially become a British colony until 1920.

Around 1900, the Kenya-Uganda Railway made its way from the coastal port city of Mombasa into Kipsigis territory. Along with it came British colonial administrators and an army of missionaries.

The Kipsigis, who comprise 196 clans, have a complex division of labor. Each clan has unique roles and responsibilities to the larger tribe. Duties are derived from a skill that was exhibited by the original head of a family, which then grew into a clan.

The Kapasisek clan, for instance, had the responsibility of issuing blessings and leading communal prayers at “Kapkoros,” the tribe’s sacred areas. The Kapkitolek clan was responsible for sparking fires through the rubbing of sticks together during sacred rituals and ceremonies. The Kibaek clan called for rain during droughts, while there are several clans that were responsible for ironmongery, in which they burned soil to extract iron for making spears, arrows, knives and other items. All clans had a group of warriors.

Upon the railway’s arrival, the clans responsible for ironmongery threw their energy into manufacturing as many weapons as possible, while the Kapasisek clan led the people in mass communal prayers. The warriors of each of the clans grabbed their spears, draping shields across their chests, and stood up to fight.

The war had begun.

The Kipsigis, led by their chief spiritual and military leader, Kipchomber Arap Koilegen from the Talai clan, and armed with spears and arrows, organized deadly ambushes on colonial convoys along the railway line. At one point, the British were forced to request reinforcements from Uganda and the King’s African Rifles (KAR), a multi-battalion colonial regiment, to defend against Kipsigis attacks, explains David Ngasura Tuei, a Talai historian who documented this history in his book “The Once Powerful Talai Clan: A Trail of Tears.”

In 1902, the British had no choice but to approach the Kipsigis with a peace offering. They requested that Koilegen attend a peace treaty in an area of Kericho County. At the time, it was a colonial administrative post. Later, it became the Kipkelion station along the Kenya-Uganda Railway.

Displaying his deep distrust of the British, Koilegen refused to attend the ceremony, sending some of his close associates in his place. At the Kipkelion station, in the exact location where the ceremony had taken place (adjacent to the old rail line that still cuts through the grass), Tuei explains to New Lines how Koilegen attempted to use the opportunity to curse the British.

“The treaty consisted of an agreement of peace, which only those who attended know of the details. And they had agreed to cut a live dog in half, which would bond them to their words,” explains Tuei. He notes that this was not a traditional practice of the Kalenjin, and elders are still unsure why a dog was used, specifically.

“Koilegen had told his assistants that when the dog is cut in two, make the white man hold its head and the black man hold its tail, so that the dog’s screams will be directed at the white man, sending him a curse,” Tuei relates.

At the site, there are still stones encircling an area of grass where the dog was buried 120 years ago. The Kipsigis and British representatives also planted a tree, which symbolized their new peace agreement and their short-lived brotherhood. The tree has now grown tall, its outstretched branches and leaves casting a shadow over the quiet railway tracks.

Koilegen was wise not to trust the British. In that same year, the colonial government declared 90,000 acres of the Kipsigis territory to be property of the British Crown, and moved on to violently expel the Kipsigis, clearing the land for European settlement.

The lands the British annexed were the Kipsigis’ most fertile lands, where they lived and grew crops such as finger millet and sorghum. The British would eventually refer to these lands as the “White Highlands,” reserved exclusively for European settlement. The mass evictions of the Kipsigis, which began around 1900 and would continue for decades, were astonishingly brutal, with British soldiers killing and raping women, children and the elderly.

Joel Kimetto’s family was among the first to be forcibly evicted from their ancestral home in the area of Sambret, around 1904. This land was, until recently, leased to Unilever Tea Kenya, Ltd., a subsidiary of Unilever, the London-based household-goods giant and one of the largest producers of tea in the world. In June 2022, however, Unilever sold its tea business, ekaterra (which includes the global brand Lipton Tea) to the CVC Capital Partners Fund VIII for $4.7 billion.

Kimetto, who is now the head of the Kipsigis, is a member of the Kaboboek clan. Each Kipsigis clan has a “totem-being,” or a living thing to which they have a supernatural connection. These are usually animals, including insects, but can also be plants, rivers, planets or the sun — which the Kalenjin believe are also alive. A clan and its totem-being have a symbiotic relationship, with both accepting a sacred duty to protect one another.

The Kaboboek clan’s totem is a baboon. Therefore, members of the Kaboboek clan could never hurt a baboon, and they believe baboons would never hurt them. Before colonialism, members of this clan were ironmongers.

In Kipsigis culture, the families knew their territories, as well as the larger Kipsigis territory through natural markers such as hills, ridges, valleys, rivers and mountains. All of the land was communal and not formally divided.

In 1905, the British targeted a Kapkoros located on the Kipsigis’ most sacred mountain: Tulwap Sigis, meaning “mountain of the Kipsigis.” The Kapkoros areas were marked by sacred altars, called “mabwaita,” which were made from wooden posts and leafy branches bound up with vines.

Kipsigis throughout the territory would congregate at these spaces to perform rituals, including naming ceremonies for babies and the selection of each generation’s respective leaders. Once a year, Kipsigis would gather here to worship Asis in massive festivals.

“The British wanted to find the weakness of our people,” explains Kimetto, who is about 72 years old. “When they realized this altar was the space where our people gathered and made decisions, they decided to burn it down.”

The Kapkoros on Tulwap Sigis had a special meaning for the tribe: it was the first one to be built by the Kipsigis, hundreds of years ago. It was also the first to be destroyed by the British. The targeting of these sacred sites became a military trend, as the British moved to evict the entire population of Kipsigis, which numbered about 700,000 at the time, from across their ancestral lands.

“Our people had never seen something like this before,” Kimetto says. “These sacred places were respected among all the tribes, even in times of conflict. No one would ever destroy a holy place or rape and kill women. It was completely taboo in our cultures.”

The Kipsigis’ resistance would continue under the leadership of the Talai for decades — sometimes through astute negotiations with the British; other times through planning uprisings. The British imprisoned Koilegen in 1914 — and, 20 years later, also imprisoned his son Kiboin Arap Sitonik, who had replaced him as the chief leader of the Kipsigis.

Between 1919 and 1921, following the end of World War I, an additional 25,000 acres of the Kipsigis’ traditional territory were annexed by the colonial government and leased to the British East African Disabled Officers Colony, a settlement of British veterans who had been disabled during the war, according to a 1934 colonial Kenya land commission report.

The African soldiers, meanwhile, who also fought in the war as part of the King’s African Rifles (KAR), which included many Kipsigis, were awarded honorable medals. “The British gave the Kipsigis soldiers medals as rewards for fighting in their war, while the white soldiers were given our land,” Kimetto says.

According to Joel Kimutai Bosek, a Kipsigis lawyer representing the community against the United Kingdom, in the nearly 70 years that the British ruled over the territory that became known as Kenya, it confiscated 900,000 acres of traditional Kipsigis land.

It took several decades, but eventually the British realized that it was the Talai clan’s sacred leadership over the Kipsigis that was preventing colonial authorities from controlling and subjugating them.

In 1934, the British government rounded up all of the Talai, numbering nearly 700, and expelled them from Kipsigis territory, relocating them to Gwassi in western Kenya, a harsh and arid environment infested with malaria-carrying mosquitos and poisonous snakes. Colonial officials described the region as unsuitable for human habitation. Many Talai would end up dying there.

The Kipsigis no longer had their sacred leaders to protect them. The British took this opportunity to unleash extreme terror on the Kipsigis people, which haunts survivors to this day.

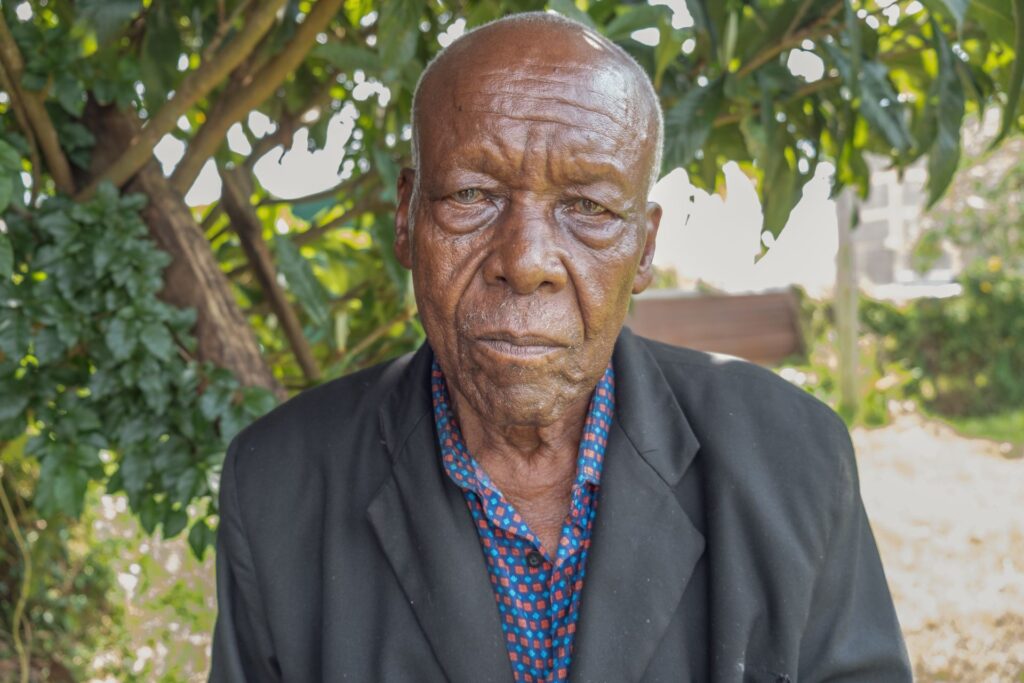

Samuel Kelowng was busy with his usual morning routine milking cows in his village in Chemogonday, now a tea estate owned by Finlays, a Scottish company and one of the world’s leading tea producers. This was around the 1950s, when Kelowng was about 10 years old. Kelowng comes from the Kamago clan; their totem is the gray crowned crane, now an endangered animal.

A group of British soldiers arrived on horseback and lit the village on fire with torches, Kelowng recounts. The family’s “korik,” traditional huts in which the Kipsigis slept with their goats and sheep, still had their livestock inside. All of them were burned alive. “My grandfather tried to salvage the goats and sheep from his burning house, and the soldiers shot him dead,” Kelowng says.

“I saw another group of white men round up all the cattle and calves,” which numbered about 100, he continues. As Kelowng attempted to save some of his cattle, one of the horses stomped on his foot. “I fell on the ground and was unable to run.” Kelowng’s eyes are large and warm. He narrates these horrors while pausing intermittently, embarrassed to speak about what transpired. “I could see everything the soldiers were doing. It was chaotic. Everyone was screaming and running. I watched the white men brutally beat my father.”

His mother was also raped by soldiers at the same time, he says. Then, a group of soldiers jumped on top of him. “One of them held my feet and another one grabbed my wrists and held my arms down.” They then took turns sodomizing him.

Kelowng screamed his father’s name, begging for help. But his father was powerless to save him. Kelowng soon fainted from the unbearable pain. “I woke up a few hours later to see blood running down my body,” he remembers. “My body ached with pain.”

His father returned to consciousness around the same time, badly injured and needing support to walk. Kelowng believes the soldiers also sodomized him. But the proud Kipsigis elder would not admit it. “I was in so much shock,” says Kelowng, looking down and recoiling from the memory. “I couldn’t speak for one week. I didn’t know human beings were capable of such things.”

Amid the chaos of the eviction, four of Kelowng’s young brothers and sisters ran from the village, never to be seen again. “Some families took many years to find each other after the evictions; some have still not found each other to this day,” he says.

Only Kelowng, his brother, father and mother remained behind in their village that had been reduced to ashes. It took them four days to limp to the Mau Forest, located in the Rift Valley and the largest indigenous mountainside forest in East Africa. His father succumbed to his injuries soon after. They survived on hunting wild animals and honey.

“After that incident, my whole life changed,” Kelowng explains. “We used to have a peaceful life. But I became ashamed of what happened to me. It casted a dark shadow over my life; even now when I think about it, it makes me cry.” He shuts his eyelids and tightens his jaw, trying to prevent tears.

Kelowng says he has been admitted to the mental hospital several times, when he “thinks about what happened too much,” and he still experiences night terrors. “I have never found another home since the white men came for us.”

Alice Cherono Tuei, who is now around 84, was about seven when a group of British soldiers on horseback arrived at her ancestral village in the area of Chepkoiben, now also a tea estate owned by Finlays. Cherono is a member of the Kapsaos clan, whose totem is also the gray crowned crane.

“Everyone in the village scattered, running as fast as they could,” remembers Cherono. The eviction took place sometime in the 1940s. “We heard rumors that these white people rape children, women and even men, so everyone was scared. I tried to run but the white men caught up to me and my friend.”

“They raped my friend until she died,” Cherono says, diverting her eyes to the concrete ground, in the sitting room of a home in Kericho town. “They burned all our homes and took our cattle.” About six British soldiers then surrounded Cherono, holding her down and forcing her legs open. She still has a mark on her inner thigh from when she says the soldiers trampled her as they took turns raping her.

She eventually fainted, and was later rescued by a group of hunters who helped her find her family, who had also fled to the Mau Forest. Her family adopted a nomadic lifestyle, defined by constant fleeing whenever news came that Europeans were approaching.

“And we’ve lived like this ever since,” Cherono says, her voice soft and shaky. “I’m still terrified of white men. I still feel a lot of fear. Every time I see a white man I’m reminded of what happened to me.”

European settlers, meanwhile, arrived at the colony to meet unfettered opportunities. According to Finlays’ website, the African Highlands Produce Company — now James Finlay (Kenya) — was set up in 1925 to acquire 23,000 acres of land in Kericho. This, the website boasts, formed part of the basis “for the Kenyan tea industry we know today.” The company harvests 28 million kilograms (61.7 million pounds) of tea annually and supplies big-name brands like Starbucks.

In the same year, Brooke Bond, then trading as Kenya Tea Company, established a vast tea farm in Kericho. Brooke Bond was bought by Unilever in 1984. As the story goes, Tom Rutter, then in charge of Brooke Bond in Calcutta, India, had come to Kenya on a hunting expedition and was delighted at the climate and ample land for growing tea.

“The [British] government started giving European settlers huge parcels of land around where the railway was passing and then went on to give tens of thousands of acres to Europeans without giving any compensation to the Kipsigis,” says Bosek, the lawyer.

The Kipsigis’ reality could not have been more different. As the U.K. created laws to legitimize its mass confiscation of land, the Kipsigis were transformed into “trespassers” on land they had lived on for hundreds of years. Most were forced onto the increasingly overpopulated and resource-limited “native reserve,” where colonial authorities severely restricted their lives.

The Kipsigis’ reserve was established on an area of their traditional lands that they normally used only for grazing their livestock. Those who remained on their lands became “squatters” and were coerced into working on European farms.

But it was not just access to large swathes of land that benefited the Europeans; colonial policies ensured that European settlers would never face local competition. Africans all over the colony were forbidden to grow cash crops — including tea, coffee and sisal — that could compete with white settlers. Price controls on African-grown maize ensured there would be no economic threat to settler-grown maize.

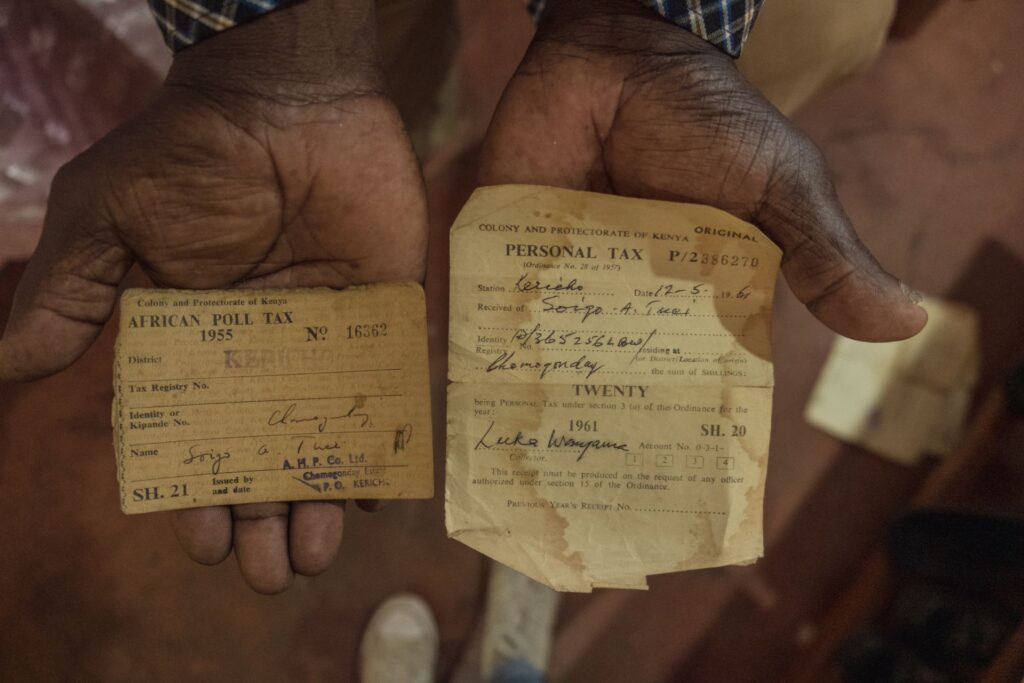

By 1920, the British had already consolidated their permit regime, aimed at controlling African movement outside the reserves. All African men were required by law to carry a “kipande,” a pass that recorded a person’s name, fingerprint, ethnic group, past employment history and current employer’s signature. It was often worn around their necks in a small metal container.

Colonial taxes enforced on the reserves, which applied only to Africans, ensured they would have no choice but to seek low-paying work on the settler farms established on their lands.

After being forcefully removed from his original village in the 1940s, near what is now the Mau tea estate, Maritim Arap Chumo, who was about 9 at the time, ended up in Cheboswa on land that was already leased to Brooke Bond.

“We were trying to find another piece of land to settle,” Chumo recounts. “We went to Cheboswa not realizing the land had already been allocated to a white man. Everywhere we went, the white people already bought up the land. But we didn’t know this. We became squatters without realizing it.”

As Chumo converses in his Indigenous Kipsigis language, the word “sikweta” punctuates his speech. It derives from the English word “squatter,” as the Kipsigis had no concept of this phenomenon before the arrival of the British. Chumo is part of the Kipkiswael clan, whose totem-being is a fox.

Now deemed squatters on Brooke Bond’s land, Chumo’s family’s livelihoods were entirely controlled by colonial authorities. In the White Highlands, African squatters were not allowed to keep cattle and could have only four sheep and three goats in their possession. Being found with more than this would result in confiscation by the authorities.

According to Chumo, at least once a year, colonial officials would come and count their livestock, sometimes arriving in the middle of the night. “If we had even one more than what was permitted, they would confiscate all the livestock,” he says.

Chumo’s family kept a subsistence garden, planting millet and vegetables, yet even this small garden required special colonial permission. His parents were forced to work on the developing tea plantation, manually clearing the land to ready it. Later, they planted the tea.

Samuel Arap Kilel’s face is severely disfigured, while his foot is partially burned off, with no toes remaining — injuries he says he sustained after a British war veteran pushed him into a fire pit while he was working on his farm in the early 1960s.

Kilel, who is now about 80, was born a squatter, knowing no other reality besides laboring for white settlers. He is from the Kapchebumbwek clan; their totem-being is the lion. “White people regarded us as animals,” Kilel says. “They never felt bad for anything. They just wanted to see the work get done.”

“Since the injuries, my brother has to assist me with everything I do,” he adds. “I cannot see or hear properly. So someone must be with me everywhere I go.”

Mitei, who was evicted from his village in the 1930s, decided to migrate to an area of the native reserve that was the closest to his ancestral lands. From there, he could see that the trees were uprooted and the fields had been cleared, mutating his home into a space that was almost unidentifiable.

“Then I saw them planting tea on the land,” says Mitei, sitting outside his current home, surrounded by expansive tea fields. Balancing a stick on his lap, he begins chiseling it with a knife. He is from the Kipsirgoik clan; their totem-being is the warthog.

Like scores of Kipsigis who were displaced, Mitei would eventually work for years as a tea picker for the same company that had grabbed his land: Brooke Bond. “When I was plucking the tea, I used to feel so angry,” he tells New Lines. “But there wasn’t anything I could do. I needed to feed myself. But I thought eventually these people would leave and then I could finally go home. Until now, I’m still waiting.”

Despite hope among the Kipsigis that the country’s independence would lead to their returning to the lands they were expelled from, instead land formerly owned by the British Crown became the Kenyan government’s land. The tea companies were permitted to continue their operations undisturbed.

According to Bosek, 200,000 acres of the Kipsigis’ ancestral lands are still leased by several multinational tea companies that acquired them from the Crown, including Finlays, Lipton Tea (formerly owned by Unilever) and Williamson Tea.

“For the Kipsigis, we never got independence,” Kimetto explains. “Still, our lands are being used by the British people. Here in Kericho, we are still a colony.”

Despite requests over the years, including through the Kericho County government, the Kipsigis have never received permission from the tea companies to visit their traditional lands, where their ancestors are buried. But Chumo still visits Cheboswa, where his father and grandfather are buried, just a few kilometers from his current home, when he has managed to get around Unilever’s security.

In Kipsigis culture, elders are the foundation and spine of their social structures, including after death. They believe their ancestors’ spirits continue to live and can offer direction to their descendants. The Kipsigis traditionally visit their ancestors’ graves when they need guidance or advice.

The Kipsigis, however, did not use memorial stones to identify the burial places of the deceased, relying instead on the natural markings of the environment. “Before, I used to know the exact location of the graves,” Chumo says. “When they began plowing the area and planting tea, they distorted the natural landscape, so I no longer know their exact place.”

“But I go to the area and I try to remember,” he continues. “I can still feel their spirits when I am close to their graves. I pray and I ask them for guidance when I am having issues in my life.” He also goes there to harvest honey from beehives that were built by his grandfather and are still located in the surrounding forests.

For the Kipsigis, their ancestors are also able to communicate to them through dreams. “When I’m near their graves, sometimes I ask them about our land,” Chumo says, sitting on a wooden bench in the yard of his current home, the sun creeping over his face.

“And in the night I see them. They come to me in my dreams. … I ask them what we should do to get our lands back. My grandfather and father keep telling me that it is not possible to fight someone who has so many bigger weapons than you. They tell me we need to find another way.”

Wilson Kipkoech Biegon, who is now about 80, was still a child when his family was brutally expelled from Changoi, which is now a tea estate owned by Williamson Tea. He eventually worked for years at a tea nursery managed by Brooke Bond on a plantation adjacent to his ancestral lands.

“Working for these companies, I never felt a single day of peace in my life,” says Biegon, who is from the Kiplegenek clan; their totem-being is the leopard.

Biegon was later able to acquire a plot of land, less than an acre, which he continues to live on. But “the land is so small,” he says, seated in his cramped bedroom. “I have nowhere to plant. Even if I had cows, there is nowhere to graze animals here. To survive, I have to buy everything. I’m not working, and my children can’t find jobs. The future of my family is bleak.”

Before colonialism, there was no concept of private land titles in Kipsigis culture. Without the natural ability to expand, Biegon’s children and grandchildren are forced to move out and find their own places elsewhere, further disrupting the central role of Kipsigis elders within their families and communities.

Nowadays, with his children moving out of the house owing to the lack of space, Beigon often finds himself with no one around to care for him in his old age.

“God gave us lands without titles,” Kimetto explains. “There was no need for these pieces of paper. These private land titles are continuing to disturb our culture and divide us from one another. It is just another invention of the white man to control our lives.”

For half a century after the country’s independence, the Kipsigis remained divided; their past and present were distorted, cracked and blurred into an uncertain future. “Colonialism destroyed our culture and the togetherness of our people,” Kimetto tells New Lines. “Our people were left scattered in different directions. Families themselves were separated. Family structures were distorted. We no longer knew who we were.”

This festering colonial trauma has, at times, been ripped wide open. In 2008, following disputed elections in Kenya that resulted in about 1,300 deaths and hundreds of thousands displaced, the Kipsigis youths’ anger finally boiled over. Attacking the multinational tea farms, they burned the fields and set alight the factories. A few years ago, the youths, armed with machetes, organized themselves into groups of 10-20 people and carried out raids on the tea plantations, stealing tea from the fields and clashing with security guards attempting to stop them.

“The youths were thinking, ‘We don’t have money. We don’t have jobs. And these people are getting rich growing tea on our land,’” Kimetto explains.

But, in 2012, on a quiet and still afternoon, something changed. Kimetto received a powerful vision; it would position him in a sacred role among the Kipsigis and their struggle to mend these colonial traumas. He believes this message was communicated to him by God.

“A vision appeared to me,” Kimetto says, sitting in his living room at his home near Kericho town. “It was like a strong calling. … It was telling me that I needed to liberate the Kipsigis and return them to their former glory. … In this vision, God commanded me to ‘save the Kipsigis people,’” he recounts. “I asked myself ‘How?’ A voice came to me and said, ‘Unite them.’ But, still, I didn’t know how. It is difficult to unite a single Kipsigis family, never mind the entire tribe.”

The voice returned. “Group them according to the clans,” it said; the clans themselves must repent for their sins, ask for forgiveness, and then “everything stolen will come back to you.”

Kimetto began the process of collecting leaders of all the 196 clans together, calling for tribe-wide meetings for the first time in more than 100 years.

Through the clans, the Kipsigis began tracing their oral histories to determine what sins they had committed against others. In Kipsigis tradition, they purify their souls by repenting for these sins — apologizing for their ancestors’ misdeeds and, when needed, providing compensation to the descendants of the individual or tribe that was wronged.

Kimetto, along with other Kipsigis elders, also approached the disgruntled youths. “We told them that when they attack the tea plantations they are destroying their own properties,” Kimetto says. “We convinced them to allow us to first try and fix this by following the law and getting our land back in a peaceful way. And they have agreed to listen to us.”

Slowly, the Kipsigis have begun to heal.

Now, they want the U.K. government to be involved in this sacred process. “We can never truly heal until the British repent for their sins and also heal,” Kimetto says. “When you commit a sin, unless you repent for it, then that sin will remain with you forever, and you will pass it down to future generations.”

Despite the strides the clans have made over the years to reunite, “the Kipsigis people can never heal from these atrocities until the land is returned and we can finally come back together,” Kimetto tells New Lines.

The Kipsigis are demanding an apology from the U.K. government, along with a sincere admission of the atrocities they committed. In addition, the Kipsigis want $200 billion in compensation for the damages caused to the clans and a full return of their communal lands that were stolen.

Along with the U.K., the Kipsigis are also petitioning the Kenyan government, urging it to jettison or refuse the renewal of these colonial-era leases — most of which are now expired — and to begin the process of returning these lands to the Kipsigis through the provision of a communal land title.

In 2019, the Kipsigis, along with the Talai clan, filed a complaint with the United Nations, calling for an investigation. In 2021, the U.N. sided with the Kipsigis and wrote to the U.K. government criticizing its failure to provide “effective remedies and reparations” over these colonial-era injustices.

The U.K. government, however, has refused to respond meaningfully to these demands. In August 2022, the Kipsigis filed a case against the U.K. at the European Court of Human Rights.

Since 2018, the elders have been registering the surviving victims, who now total 115,000.

Kimetto arranged for New Lines to interview some of the victims at his home, near Kericho town. Since the expulsions left the Kipsigis scattered in various locations, some traveled for hours to the planned meeting.

Sharing tea and bread while waiting for the victims’ arrivals, Kimetto and Tuei explained the history of the Kipsigis. Since the Kalenjin are believed to be descendants of a tribe of the ancient Israelites, the Kalenjin languages share various words with ancient Hebrew. All of humanity are descendants of “Adam ak Awa” (Adam and Eve), the original ancestors, they say.

In Kalenjin oral history, their “greatest prophet” was “Musaiya,” or Moses, who led their ancestors across the Red Sea. The ancestors of the Kalenjin returned to Egypt following a prolonged famine in ancient Israel.

Kimetto, Tuei and Peter Bett — head of the Kipsamaek clan — sing a song for New Lines, which has been passed down for generations among the Kalenjin since the time of Moses, thousands of years ago. The chorus repeats: “If it was not for Musaiya [Moses] hitting the deep waters [the sea], we would not be here.”

The first victims trickle into Kimetto’s home. Then more arrive — and more. When word spread that a journalist was here to document stories of colonial injustices, many more than had been requested traveled to Kericho town.

Lined up outside Kimetto’s living room, they were eager to tell their stories and show scars from when they say British soldiers beat and raped them. New Lines was unable to interview all of them.

Rusi Chepngeno, now 75, was about 10 when she says four British soldiers gang-raped her during forced evictions that displaced her family from their ancestral home in the Chagaik area, now a tea estate by the same name, which until recently was owned by Unilever.

Chepngeno is from the Kibasisek clan, whose totem-being is “Asis,” the word for both God and sun in the Kalenjin languages. Their sacred duty to the rest of the tribe was to provide blessings and lead communal prayers.

She lifts up her dress to show scars on her thighs and legs. She says some of them were caused by the soldiers hitting her with a bayonet while they forced her legs open. Others are imprints from the men’s shoes as they stomped on her while they took turns raping her.

Evelyn Chelangat Kikwai, 72, was born in Chepchabas, now a tea estate owned by Finlays. Her father was from the Kapmochilek clan, whose totem-being is a fox. Her mother was a Talai.

Kikwai can barely get through a sentence without burying her face in her palms and sobbing. She was only about 3 when she says her family was evicted from their home and all their property was confiscated. She shows a mark on her leg, sustained from when British soldiers raped her mother in front of her; their heavy boots stepped on Kikwai in the process.

Wilson Kiplangat Kiget, Ruse Arap Boen, and John Kimutau Arap Kiget are triplets, who are about 80. This colonial violence is documented in their genetics. They were born as squatters on their ancestral land, also Chepchabas. At that time, the land was leased to the Bureti Tea Company. Now the estate is owned by Finlays.

They say a British settler employed by a security company hired by Bureti raped their mother, resulting in her getting pregnant with them. “The only time we ever heard about our father was when our mother would curse him for raping her,” Ruth tells New Lines.

When they were around 3, their mother was brutally evicted from Chepchabas. In the middle of the night, British soldiers burned their homes, they recount. Their mother grabbed them and fled as fast as she could. Along the way, something sharp pierced Ruth’s right eye, permanently blinding her.

New Lines did not have time to interview Anah Chepkwony, who was waiting outside in the hallway. But the 84-year-old approached this reporter on her way out. Chepkwony lifted her dress to show scars running down her legs. “They beat me with sticks,” she says, hurriedly. “The [British] soldiers gang-raped me.”

Old, broken pieces of Kipsigis traditional pottery are unearthed each time the tea plants are uprooted on the estates. “This proves that our people lived here,” Kimetto says, as he retrieves shards of the pottery from a plastic container and balances them on his palms.

“When the British came and destroyed our homes, they also broke the pots; but the soil cannot degrade them.” There are also “hut sites” dotting the lengths of the tea estates — bald patches in a sea of green where tea is not able to grow. These areas are in locations of the Kipsigis’ “korik,” or traditional huts, that British soldiers burned to ashes.

Kimetto, who worked for 35 years as a researcher with Brooke Bond, says this is because the soil is too alkaline (it contains large amounts of potassium or sodium carbonate) from fires the Kipsigis made in the center of their homesteads, along with the buildup of urine from the goats and sheep who shared their huts with them.

“This, to us, is proof that God is protecting our homes until we can finally return to them,” Kimetto says. “And God is showing the British that this land does not belong to them. Each time they walk past these bare spots of earth they will be reminded that this is where you destroyed someone’s home.”

“Our pottery is still in the land,” he continues. “It is our ancestors whose bones are being unearthed. All of this is proof that this land rightfully belongs to the Kipsigis. Yet it is still being used by the British.”

Kimetto has a sharp warning for the U.K. if the government continues to ignore their cries: “The lands are here with us. We are following the law to try and get them back. But if the British do not listen to us, we will have no choice but to pass the torch to the youths.”

“We don’t want to reach that stage,” he adds. “But we will soon come to a point when we won’t have hope anymore in solving this in a peaceful way. And when that happens, we will no longer be able to control our youths — and they will take back our lands by any means necessary.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.