Writing on walls is as old and common as writing itself. Walls carry the names and romantic words of lovers, the contact details and professions of manual workers seeking work and sometimes specific instructions such as “Do Not Litter.” In Mosul, which has come under various rules in its recent history, these scribblings tell many stories and mark different eras.

The battle for Mosul began in October 2016. The Iraqi army, Counter Terrorism Service, Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and Federal Police participated in the internationally backed grueling battle to retake the city. The urban fight lasted almost nine months, and Mosul was declared liberated from the Islamic State group in July 2017. During and after the battle, the participating security forces wrote graffiti on walls. These writings varied from random cellphone numbers to open messages to the people of Mosul. One of the first things my eyes caught was the “Fuck ISIS” on the dome, leaning minaret and niche of the Nuri mosque. The destruction of the Nuri mosque’s minaret by the Islamic State sparked a debate on social media at the time. Some odd posts expressed schadenfreude because it was at its pulpit where the self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced his rule over large swaths of Iraq and Syria in July 2014.

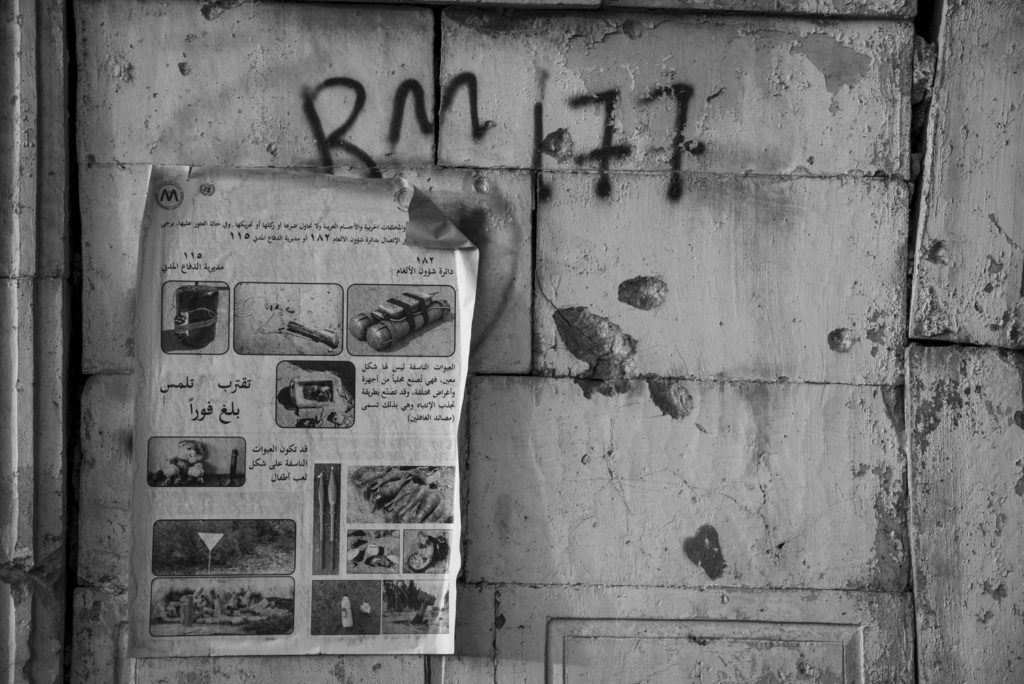

The battle for Mosul is the second-longest urban battle in modern warfare. It left behind tons of unexploded bombs, shrapnel, suicide vests and dangerous objects. Iraqi military engineering and the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) started scanning the Old City to clear it from this hazard. I noticed some graffiti warning people who returned home of this massive risk. Some walls carried the words “safe,” while others were marked “hazardous,” denoting that work was ongoing to clear the Old City of harmful objects. In an awareness-raising video posted by the UNMAS about three years ago, Paul Heslop, the mine service’s program chief, shares horrific statistics about what the war left behind. Realistically, it could take no less than 10 years to fully clear Mosul of the detritus of war. He drew a mind-blowing comparison of what he saw in Mosul with other scenes from Munich, Warsaw and Coventry after World War II. This scale of destruction and its malicious legacy is so haunting that no month passes without finding small grenades, explosive vests or even missiles.

The war ended in July 2017, but the graffiti continued to grow. New people, NGOs, government institutions and even international agencies used Mosul’s walls to leave messages. The Old City of Mosul was evacuated because of the ferocity of the battle, mass destruction and risky alleys. The densely populated area turned into a ghost town. Aerial footage showed World War II-scale destruction. All public services halted. Power grids, water pipe networks and sewerage systems were down. Eastern Mosul, on the other side, became even more densely populated, causing home rentals in that part of the city to skyrocket. Some families who could not afford it decided to go back to the Old City despite the risks.

The graffiti that became popular back then was “families are here.” It was a desperate call for help where no government institutions or NGOs had returned to that stricken zone. The wait did not last long. Mosuli activists and volunteer teams cast campaigns to help. This motivated many international NGOs to help the returnees with food, water tanks and other basic needs. I spoke with one of the volunteers to understand the context behind those writings. “The Old Town was emptied and very few families made it home. It was too difficult to find a house with a family as the alleys were too narrow and quiet. We found returning families through this graffiti,” says Ola Al-Othman, founder of a local NGO. Other families did the same, and now it’s part of the wall’s history. Life is now fully back to most of the Old City, and the famous graffiti is still there telling the story of how life came back, reviving the sounds and scenery of the narrow alleys.

In the same Old City context, people want to denounce the accusation that the Islamic State group is the representative of Islam. In this case, I found one graffiti that says, “ISIS belongs to no religion.”

In other places, the PMF had their own share of Mosul wall writings and pro-PMF graffiti was a common sight. When the U.S. Treasury in March 2019 blocked the financial assets of Akram Al-Kaabi, leader of the Al-Nujabaa militia, based on terrorism charges against him, militants from various PMF groups roamed the streets of Mosul in their SUVs, displaying their weapons to challenge the designation.

They painted the walls with a hashtag in Arabic that meant “We are all Nujabaa” to denounce the sanctions. Another PMF faction, Babiliyoon, led by the U.S.-sanctioned Rayyan Al-Kildany, a Christian, marked their presence in Mosul by writing on an ancient church in the Old City of Mosul.

The messages on the walls popped up all over the Old City. Some of the graffiti mentioned the hometowns of the soldiers, like Talafar, Basra, Maysan and others. On this wall, a soldier was telling the people of the neighborhood to remember them whenever they are safely back in their houses: “Mosulis, remember that you are back here by the blood of our forces.”

When the Islamic State group took over Mosul back in June 2014, they seized all government institutions and facilities. They also confiscated property and assets of Christians, Izidis (Yazidis) and the Muslims who fled the self-proclaimed caliphate. Nearly no wall was left unmarked by the Islamic State. The infamous “baqiya” appeared on the wall of a home. Roughly translating to “remaining,” baqiya references the Islamic State’s slogan “remaining and expanding,” which became a hallmark of its propaganda and media campaigns. On other walls, the Islamic State marked the confiscated properties with one letter that represented the first letter of an attribute they gave the original homeowner. The Arabic letter for “N” was written to designate homes that belonged to “Nasara” (Christians); the “R” for “Rafidhi,” a derogatory reference to Shiite Muslims; and an “M” for the Arabic word for heretic to describe the Sunni Muslims who had left the “caliphate.”

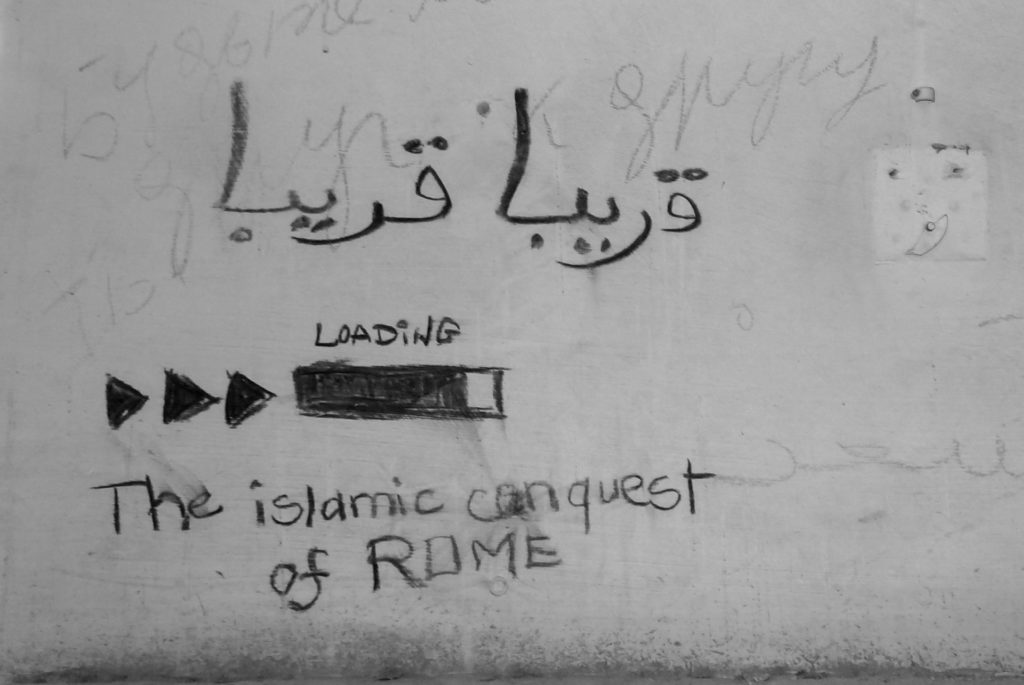

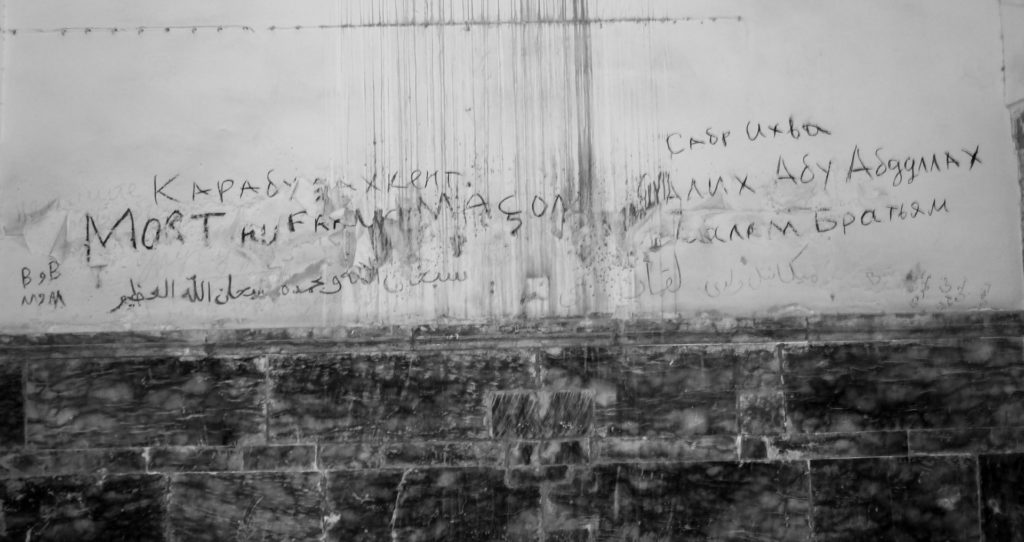

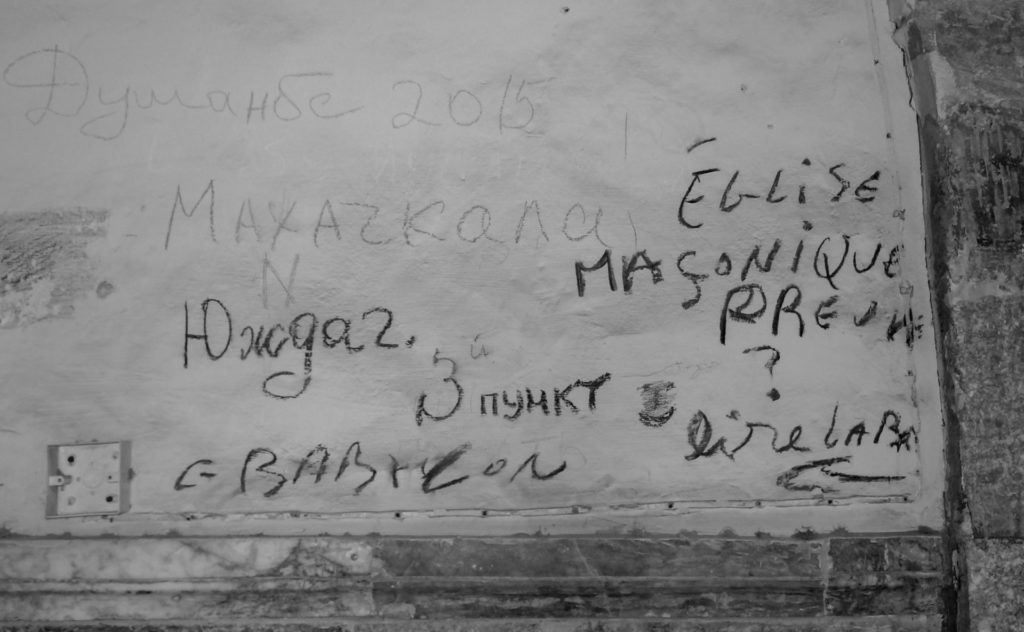

Islamic State graffiti was not restricted to ideological propaganda or confiscated property. It reflected the multinational backgrounds of their soldiers. Church walls were riddled with Arabic, English, French, Russian and Kurdish writing. In February 2015, the Islamic State group’s media streamed the brutal beheading of Coptic Christians on the Mediterranean shores of Libya while vowing to conquer Rome.

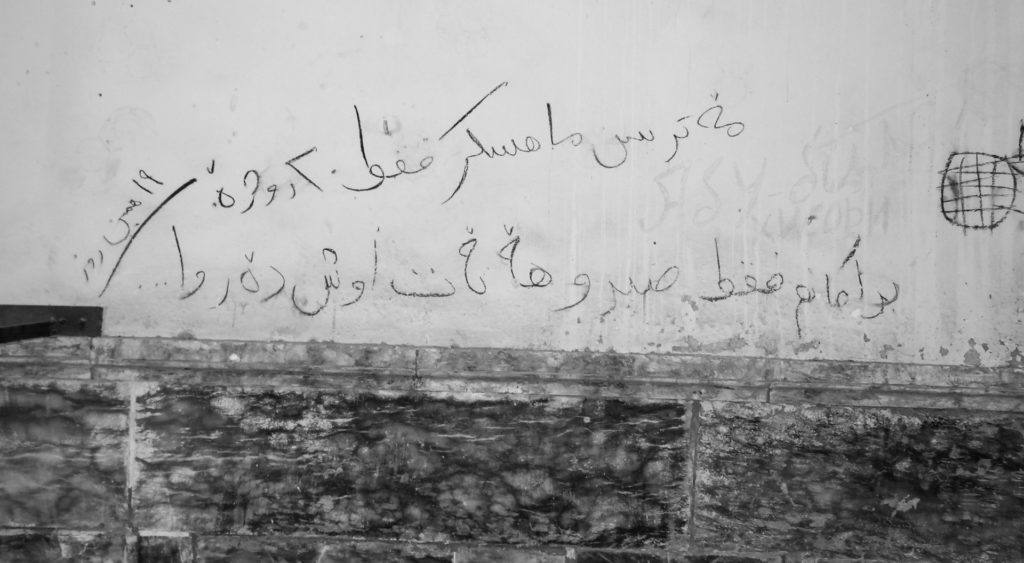

Islamic State militants in Mosul responded by putting the same slogan on the interior walls of St. Maskanta Church. On another church wall, a Kurdish militant wrote: “Day 19 of the 20 day training. Don’t be afraid, all you need is patience.”

An Islamic State militant from the city of Derbent in Dagestan, Russia, wrote: “Salute, all my brothers.” He wanted his identity known by mentioning all the cities he had been through in Dagestan, like Mikrah, Kazmalyar and Kaladzhukh.

Sitting in Mosul, I had to Google all these unfamiliar places mentioned on the walls of my city. They turned out to be beautiful, mountainous cities. What made these multinational people come under the command of someone thousands of miles away who may not know anything about them? What made them leave the Caspian shores of Derbent to come and inflict death and terror in my hometown? This intriguing question drove me to explore more graffiti. This time, a French one curses the ruling class in the Elysees: “The Mason is the killer and torturer of infants.”

These messages are only one way to prove the presence of multinational militants who gathered in Mosul and turned it into their battlefield.

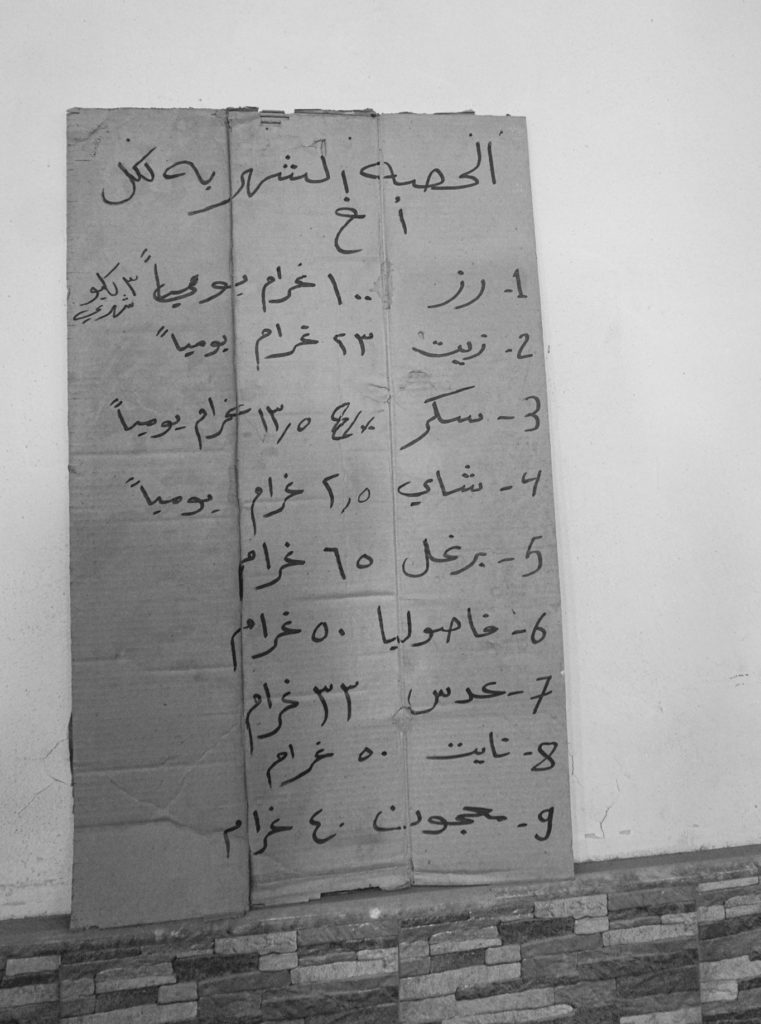

During Islamic State rule of the city, militants seized and sabotaged. They left no cross or statue intact. Some churches were used as training grounds while others became bureaus for the notorious Hesba (Virtue Police) to inflict punishment, often physical, and humiliation on locals. When the Islamic State ruled that media consumption was forbidden, satellite receivers were confiscated. I, like all Mosulis, witnessed the militants roaming every single neighborhood, alley and house to search for what they hated most: freedom. They put the check mark with the word for “done” to denote that alley clear of satellite TV receivers. They had a pretext for every act. They mentioned back then that those receivers spread vice and immorality. The Islamic State turned this 18th-century Armenian church into a compound for piling the terrestrial satellite receivers and equipment that people used to watch television, as the graffiti shows.

I spotted a very odd Islamic State phrase on a door that says: “no women allowed in, no food to give, no food at all.” This phrase had me confused until I managed to enter the yard to find the answer. That part of the Old City had been besieged for months until liberation, and people ran out of food and water. They sought help and knocked on every door. This time the Islamic State was saving food for their own militants and families. Upon entering the churchyard, I saw hundreds of TV satellite receivers. It was early 2018, and the Old City was not completely safe to walk through. I passed by battle-scarred walls and rubble to enter the prayer hall, and it was complete chaos. A banner attracted my attention. I came close and found a long list of food, drinks and even detergents for every Islamic State member. I looked around and saw scattered energy drink cans. I was not surprised. The Islamic State was, after all, doing their best to survive with their families while Mosul burned to ashes.

Families hid in basements, relying on boiled wheat grains, tomato paste soup and even grass to survive.

One last church, Mar Toma, for Assyrian Catholics, had its share of Islamic State graffiti. Peos Affas, the church manager, told me that the 19th-century building was badly sabotaged. All the museum’s ancient manuscripts were looted, and the walls were scratched with various Islamic State graffiti that glorify bloodshed in various languages. “Most of them were removed,” he said. Peos made sure to revive his church, including covering the walls with photos documenting the stages of recovery and returning the church bells to service.

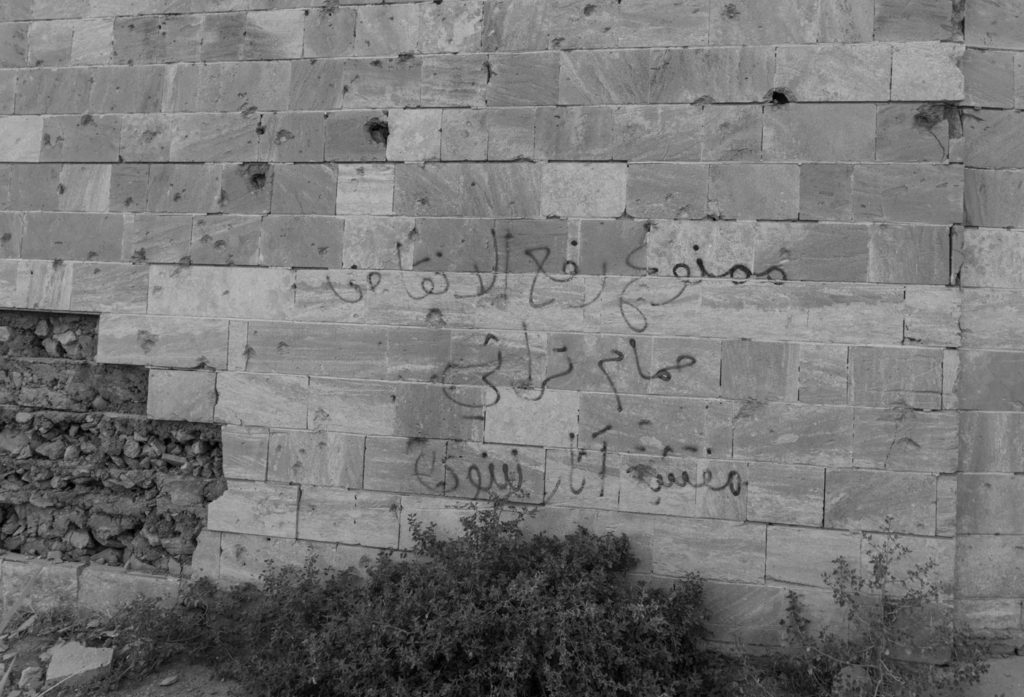

What happened to the Old City during the battle was not only because of the ferocious urban battle. It was a combination of factors, including poor public services and weak preservation of the landscape. Most important, the heavy bombing demolished large swaths of the Old City. While walking, I could see scores of leaning, dilapidated buildings and houses. To warn the pedestrians, their owners left signs and graffiti on the walls, including on the famous twin minaret Al-Saffar mosque by the Clock Church. Warning signs in bold tell people to avoid walking by because the tall twin minarets are seriously “ramshackle.” I managed to spot the same warning sign on a damaged and abandoned home. The owner left the message to guarantee nobody is harmed and detach himself from liability.

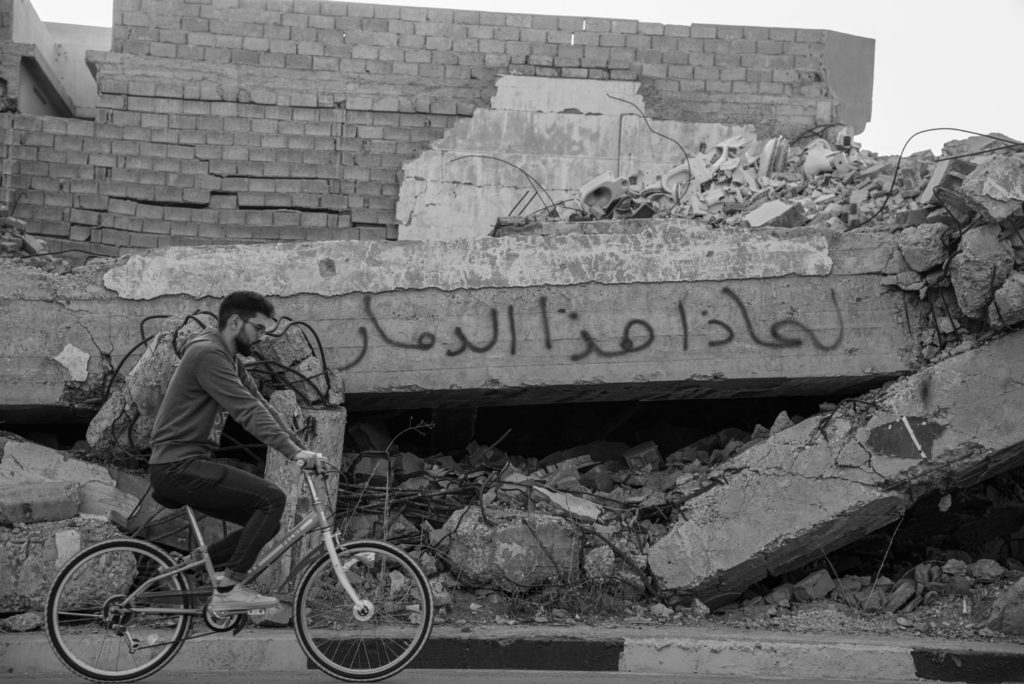

The riverside Old City façade was the last spot to be cleared of the Islamic State in July 2017, so it naturally endured the brunt of the battle. Islamic State militants were cornered there and used civilians as human shields. Most of the picturesque area was leveled. The few intact houses faced another brutal fate. The chaotically managed local administration wanted to implement certain plans to fix it. Then the notorious governor, Nawfal Al-Agoob, now sentenced to five years on corruption charges, among other issues, led a devastating campaign to raze the entire area. Property owners came together to try to stop the authorities. They scribbled their houses with calls to not flatten their undamaged properties: “Do not crumble my house.”

Other people whose homes were demolished also came there for quite a different reason. Their words conveyed a lifetime of memories. Some of them scribbled heartfelt messages on the walls: “Here I used to have memories, home sweet home, what has time done to you. … !”

Others asked questions: “What is all this destruction for?” wondered one brokenhearted Mosuli.

The war ended with no clear death toll announced. The local authorities, including the Civil Defense Unit, had the capacity to clear the entire area of bodies amid the rubble. However, activist Suroor Al-Husseiny rolled up her sleeves and undertook the hazardous task of clearing the riverside façade and other parts of the Old City of bodies, mainly Islamic State militants and civilians. The Arabic phrase for “there are bodies here” motivated Suroor to take action. Supported by her volunteer team, Suroor did most of the heavy lifting to make the Old City cleaner and safer despite continuing harassment from local authorities.

Many families partially or fully lost their houses. They called on volunteer teams and government directorates to help them remove the rubble so they could return to their neighborhoods.

Many responded, highly motivated despite the risk. However, other graffiti warned not to remove any rubble as some places were marked as “ancient heritage site” by the Heritage and Antiquity Directorate (HAD). Abdulrahman Emad, a HAD official, explained that because of a lack of resources and staff, they started slowly in 2017 by marking the hundreds of ancient valuable locations in the Old City with messages dictating the preservation only of what is left of the ancient structures. “Some people may not know the significance or ancientness of the places nearby their neighborhoods; that’s why we marked them,” he added.

Internationally, various organizations have been active around Mosul with significant attention to the Old City in particular. UNESCO is one of the partners that raised over $50 million to “Revive the Spirit of Mosul,” including the Nuri Mosque, the Clock Church, Tahera Church and 125 ancient houses. The European Union along with the United Arab Emirates are the major donors of this initiative to revive ancient houses in the old cities of both Mosul and Basra. On the Mosuli part, “The EU grant is helping training youth, men and women, on ancient house preservation and rehabilitation,” said Moyasser Naseer, UNESCO media adviser. “The work is being done on many phases; some houses have been already handed to their owners; work is being done on others.” The EU and UNESCO names can be seen on many Old City Mosuli walls.

Despite signs of life returning to Mosul, the “house for sale” remains the most prominent graffiti in the Old City. One real estate office name is scribbled all over. As I walked through the alleys, the graffiti led me to real estate agent Sarmad Mahfoodh, whose office is located in a ramshackle building with broken windows, hanging metal bars and many offers of property for sale. “People want to live in bigger homes,” Mahfoodh said. “Prices are now on the rise, which start from $10,000 a house.” Demolished houses are hard to rebuild and even harder to live in. Most neighborhoods are laced with cruel memories and poor public services. However, that is not the full story. The Old City has received media coverage, including attention on the heritage sites and humanitarian aid, both locally and globally, like no time before. On the heritage side, I met with a local activist, Saker Al-Zakariyya, who founded his preservation organization, Baytna Institution, four years ago in the heart of the Old City when there were no public services, paved streets or secured facilities. “Rents were down to $80 a month, while now I pay over $300 a month,” Saker says. Other youth-led NGOs were drawn by the magic of the place, which attracts plenty of media, tourists and vloggers. Added to that, international figures like French President Emmanuel Macron, Pope Francis and many ambassadors describe the Old City as their favorite destination during their visits to Mosul.

Some of the city’s Christians have returned to either live, secure their houses or sell their assets and leave Iraq for good. The Christian neighborhoods are decorated with crosses with replaced Islamic State graffiti, though most of the houses are still chain-locked from the outside.

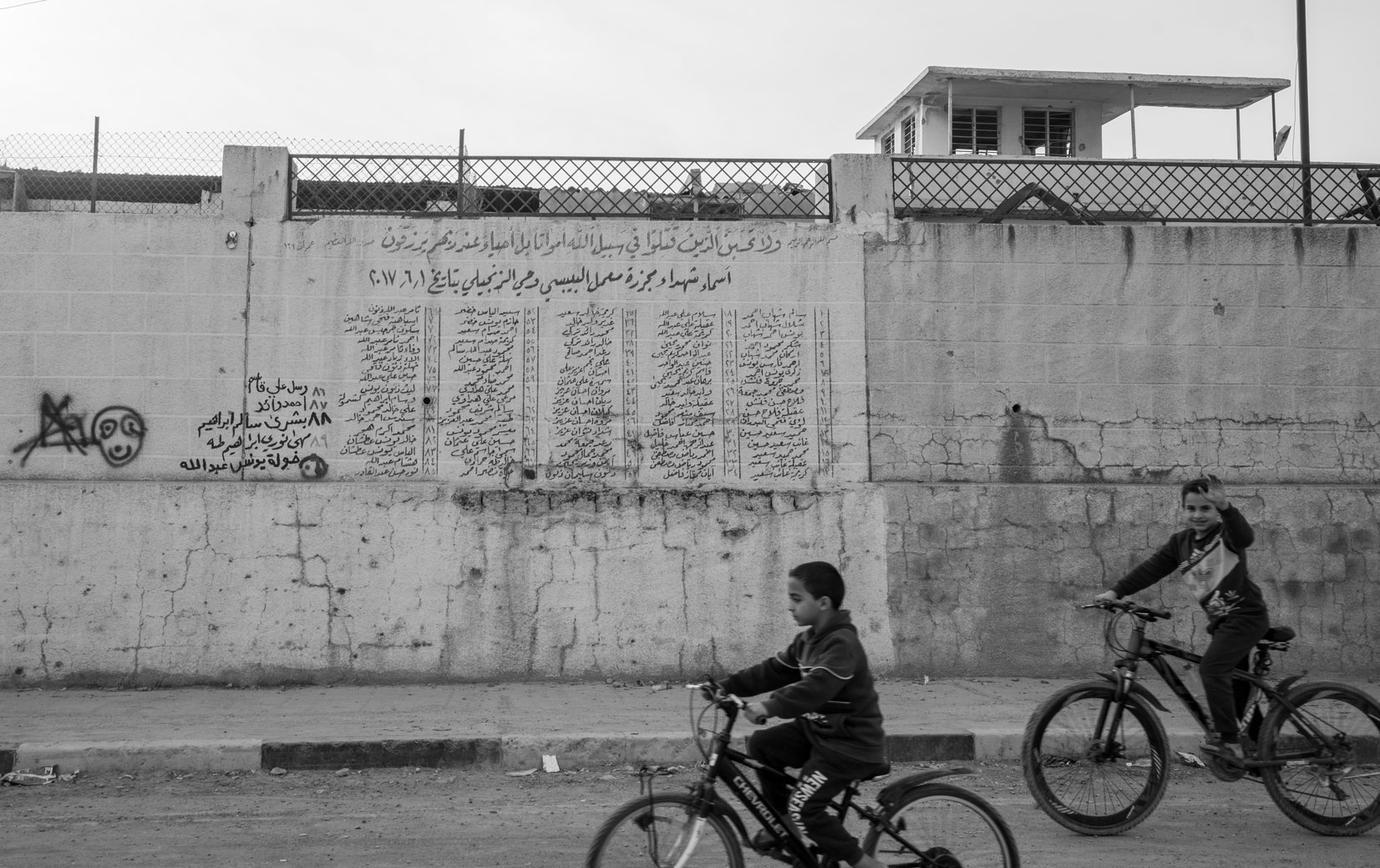

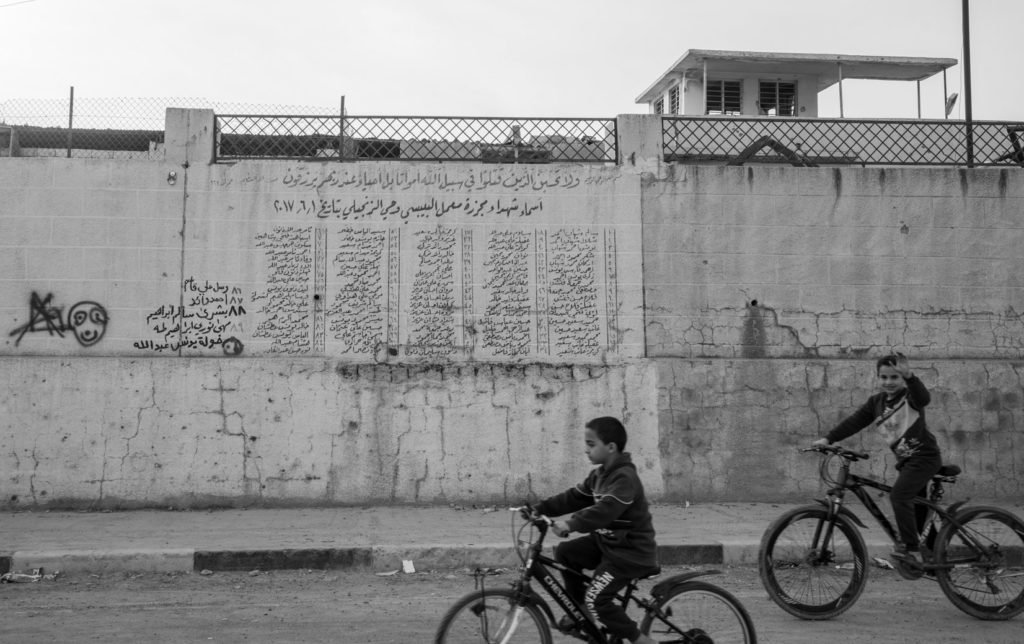

Massacres documented on some walls capture the painful side of the story. Entire families were annihilated either by mass bombing or Islamic State attacks. Around the Old City, I photographed this memorable graffiti of a large family killed in an airstrike: “Jabban family alley, 16 members.” To see if this method of expressing grief was common, I went to another infamous site: the Zanjili district in Western Mosul. When families tried to escape via safe humanitarian passages, an Islamic State fighter had other ideas as he opened fire, killing entire families. I saw some dramatic footage. The Iraqi army and Free Burma Rangers, a Christian humanitarian group, managed to drag some wounded people to safety. One child looked completely traumatized as she was given a bottle of water. The date of June 1 with a list of over 100 victims was inscribed on the very wall where they were killed lest people forget, lest the world forget.

Mosulis, like Iraqis elsewhere, are still dreaming of improved living conditions.

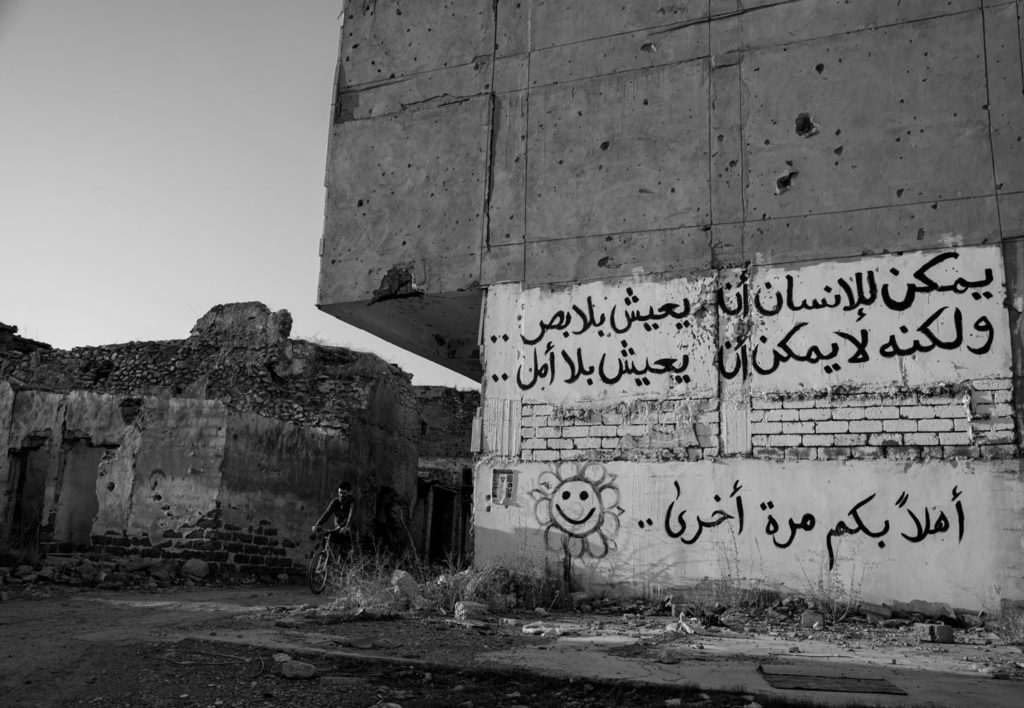

In other places around the old bazaar, rebuilding and returning to the abandoned places has become a celebration. The phrase “the auspicious return” was coined to express this joy, and the dates when the area was inhabited again are marked. This positive, hopeful graffiti was put around the ancient Saray bazaar, which was demolished during the battle and is now buzzing with life again.

One local artist wrote a verse on a bridge walk from the late iconic Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: “It is still worthy to live on this land.” Such powerful words took me to street artist Abdulrahman Saad, who started painting murals over Islamic State propaganda. “It’s a message that art is back, hope is back, and it is our moral responsibility to raise awareness about it,” Saad said.

Graffiti is part of the walls of every city. In some cities I have visited, they form the artistic identity of the place. In Mosul, graffiti not only is art but also has chronicled historic events and their implications. From lovers’ initials to free well water signs to the number of victims killed to messages about an imperial-like conquest of Rome, the issue could not be more compelling to me. However, these messages are not eternal. Walls get painted, crumble or are rebuilt. Some of the graffiti disappeared a few months after I photographed them. From this point, I have made a resolution to document Mosul’s walls and what stones may speak on behalf of their inhabitants.