On a cold, bright morning in early March, a small group of women and children carried empty jerry cans up an icy slope in Kumik, one of the oldest and most remote villages in northwest India’s Zanskar Valley. Despite the sun bearing down overhead, the air was cold, only 14 degrees Fahrenheit. Their destination was the mouth of a narrow, black water pipe, buried beneath a fresh layer of snow. When they reached the small mound of rocks marking the site, they took turns filling their vessels. The process was arduous. It can take up to 10 minutes to fill a 5-gallon container. In a village that once enjoyed abundant water resources, it was all that was left.

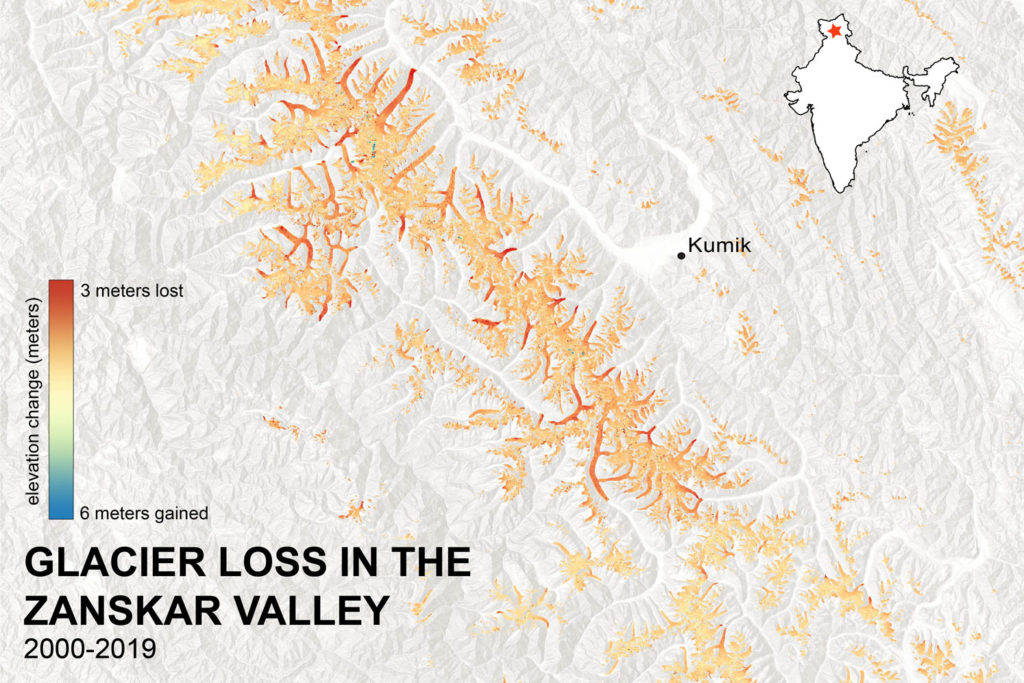

For decades, the people of Kumik have been in the throes of a water shortage crisis that has dramatically worsened in recent years, forcing some residents of the tiny community to leave their ancestral home. Kumik sits at the foot of Sultan Largo, a jagged mountain capped by a quickly depleting glacier. Villagers say that some two decades ago, snowmelt from the mountaintop replenished Kumikthu, a serpentine stream that runs down the slopes of Sultan Largo into the village, where it irrigates fields of barley and wheat. But conditions began to change dramatically in the late 1990s, after a winter of unusually little precipitation. Tsering Dorjey, an elderly resident of Kumik, told New Lines that since then, he has watched the village run dry before his eyes.

“When I was young, you had to be careful while crossing the stream [Kumikthu]. It gushed with water,” he said.

The Zanskar Valley, home to around 14,000 people, is considered a “cold desert” because it receives as little as half an inch of rainfall annually. For millennia, the residents of its sparsely populated villages have relied on glaciers to feed the streams that make life in the remote region possible. The setting of a 2015 book by Jonathan Mingle and numerous other publications, Kumik is the most famous example of how the disappearance of those glaciers can upend livelihoods and has become an omen for the rest of the region. But new reporting by New Lines indicates that the water shortages in Zanskar are part of a string of related crises that have begun to play out across the Himalayas, which scientists predict will only worsen over the course of the century.

The system of contiguous mountain ranges that run from Afghanistan to China, which includes the Himalayas, the Hindu Kush and the Karakoram, is often referred to as the Third Pole because it contains the world’s third largest storage of frozen water. Glacial runoff from the mountains feeds some of Asia’s most important river systems, providing drinking water, sources of irrigation and hydroelectric power to communities across the Himalayas and to the densely populated urban centers downstream. But those critical ice reserves are quickly diminishing.

A study published in Nature last April found that glaciers worldwide have lost an average of 250 metric gigatons of ice per year over the past two decades, a rate equivalent to approximately 20% of observed sea-level rise. In the Himalayas, the situation is particularly precarious. Last year, a team of researchers from the University of Leeds found that glaciers in the Himalayan range have lost around 40% of their total ice volume since the Little Ice Age, an epoch of global cooling that took place between the 14th and 19th centuries. At the current rate of global warming, the United Nations Development Programme estimates that the region’s glaciers will lose up to two-thirds of their ice volume by the end of the century. Even if the increase in global average temperature is capped at 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the target set by the Paris Agreement, Himalayan glaciers are still projected to lose one-third of their volume.

The impact of climate change on the region’s glaciers is being compounded by black carbon pollution originating from industrial facilities and heavy vehicle pollution in the urbanized regions of South Asia. These small particles, which are generated by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass, are estimated to account for approximately 50% of recent snowmelt and glacier loss in the region, according to a 2021 report by the World Bank. When the fine particles accumulate on snow and ice, they heat the air around them and increase the surface absorption of solar radiation, causing the ice to melt faster.

The melt will have severe humanitarian consequences for the Himalaya’s 240 million residents and the more than 1.7 billion people living downstream. Experts have predicted reduced agricultural productivity, particularly in areas like the Zanskar Valley, where many agrarian communities derive all their irrigation water from glacial runoff. More than 100 million farmers in India and Pakistan get their water directly from the Indus and the Ganges, large snow-fed rivers that will shrink over the course of the century. Other projected impacts include diminished hydroelectric power production and an increased likelihood of glacial floods, extremely dangerous events with high casualty rates and costly damages.

The ways these dynamics are playing out in communities across the region in the short term depend on a number of factors and can appear incoherent. In the neighboring village of Stongde, some streams have swelled, while in Kumik, water sources have diminished more each year. Michel Baraer, a professor and hydrology expert at the University of Quebec, said that the flow levels of glacial streams depend on the stage of melt that a glacier is experiencing.

“When a glacier starts retreating, it’s losing mass, [and] this mass just feeds the streams that flow from the glacier,” Baraer said. “So that means at the early phase, you see an increase in the discharge of those streams.” But in the final stages of melt, he said, the glacier “has lost most of its influence on the discharge of the stream,” leading the water level to stabilize at a volume significantly lower than its original one.

Of the millions of lives projected to suffer the consequences of glacier melt in the Himalayas, Baraer said that alpine communities like Kumik will feel the effects soonest and most severely. In the same way that a shard of ice will melt faster than a large cube, he explained that the relatively small glaciers that feed local streams will diminish more rapidly than the massive ice reserves that feed Asia’s largest river systems.

“Those communities will have to cope with water scarcity,” Baraer said. “Because those phenomena are not reversible, right? When the glacier is gone, it’s gone. It will not come back.”

More than 300 miles southeast of Kumik in the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh lies the Spiti Valley, a picturesque mountain pass that sits at an elevation of more than 12,000 feet. In the summer months, tourists from around the world visit the valley to explore its unique landscape, dotted with Buddhist stupas and centuries-old monasteries perched on crags. But in recent years, a worsening water crisis has caused tourism to decline.

Locals in Chicham village told New Lines that the heaviest snowfalls have begun to arrive late in the winter, rather than at the peak of the season. Since the temperatures are higher at that time, the snow melts quickly and gushes down the valley instead of replenishing glaciers at the mountaintops. Tsering Tashi, a farmer in Chicham village, said that the most crucial precipitation occurs between December and February, when the snow stays at its source for longer and trickles down the valley slowly.

“The snowfall in late winter is heavy with water and that does not stay for long on the mountain,” he said. “That snow doesn’t help.”

Kalzang Ladey, another farmer in Spiti, told New Lines that he believes the problem will only intensify in the future. The valley’s crops are typically irrigated around June and July but since the snow has begun to melt much earlier, the fields have gone dry and harvests have withered. This past year he sowed crops only on 20% of his land because he did not have enough water to irrigate his entire field.

“We used to cultivate barley, peas and other vegetables and sell them in the market. But now, we barely manage to grow enough for our families,” he said.

Natural springs and “kuhls” — diversion channels that carry water from glaciers to villages — are the main sources of irrigation in Spiti Valley. The region’s worsening water crisis has made the careful preservation of water in these reserves especially critical. But farmers complain that many of the kuhls, which are estimated to account for more than 80% of the valley’s irrigation sources, are in dire need of repairs.

“Since these water channels span long distances, there are high chances of water losses,” Ladey said. “Many kuhls need repair but the government is not paying any heed.”

Prem Chand, the revenue officer for Spiti Valley, told New Lines that such repairs will not substantially improve the farmers’ situation.

“The [glacial] water sources have dried up. The springs have also dried up,” he said. The problem, he argued, was not with the kuhls but with the unrelenting disappearance of the region’s most precious resource.

When Kumik’s streams began to run dry, a group of villagers hiked to the summit of Sultan Largo to find a way to reroute the water to their village.

“There was little of the glacier left. And whatever was left trickled down the other side of the mountain to another village,” said Kumik resident Richen Dorjey, 50. The group tried to dig channels down the side of Sultan Largo, but the task proved dangerous and enormously difficult without the use of heavy machinery. Richen, who helped dig the canals, said that he permanently injured his spinal cord in the process. Ultimately, the villagers did not have enough labor and resources to successfully divert the water toward their homes.

“It was like turning the mountain. How could we do it without the government’s help?” Richen said. “The government never helped.”

Phunchok Tashi, a counselor in the regional government, told New Lines that funds were not allocated because the deteriorating conditions of the nearby glaciers made the project “infeasible.”

In the early 2000s, when hopes of the water shortage ending began to fade, Kumik residents approached authorities in the regional capital for assistance. Officials in Kargil decided to allocate funding toward building a new village called Lower Kumik, where water for irrigation would be made available by the construction of a 4-mile-long canal. The government would pay future residents of the village to build the waterway, which would reroute a tributary of the Zanskar River. After the project’s completion in 2007, 20 families — about half of Kumik’s population — relocated to the new village.

Today, the level of water availability in Lower Kumik is enough to support life, but still far from ideal: Villagers must take turns irrigating their crops, and in the winter, when natural sources of drinking water freeze over, the community relies on deliveries from a tanker truck. When the roads are closed, the truck doesn’t come. Tashi Stobdan, a government teacher who relocated to Lower Kumik 15 years ago, said that while the community is learning to live in the new environment, he is not hopeful about the village’s future.

“This canal is not sufficient if everyone from Kumik migrates here. There has to be an alternate source,” he said.

Phunchok Tashi said that the government is trying its best to support Lower Kumik.

“We are planning to strengthen the canal in Lower Kumik. We are also setting up hand pumps to meet the villagers’ drinking water needs. We are doing whatever can be done,” he said.

Back in Kumik, residents have learned new ways of living with perpetual water shortages, at least for now. They built a small dam in the foothills of Sultan Largo to feed their animals and dug intricate irrigation channels around their fields to maximize the irrigable land area. Like the villagers in Lower Kumik, they take turns watering their fields in the summer. And for drinking water, they built a pipe to capture water from the mountain’s creeks and transport it to a source close to their homes.

Some residents who have chosen to remain in Kumik said their decision stems from a lack of resources to relocate.

“Those who have moved had either jobs or enough savings to build new houses,” said Stanzin Spamber, a farmer in Kumik. “Many like me here are poor farmers. We live hand-to-mouth.”

Spamber added that the people of his village are deeply attached to the culture and the history of the village.

“It’s difficult for us to leave behind the legacy of the land where our ancestors lived and died,” he said. “We have a spiritual attachment to this place.”