It was early fall, and my elderly mother, Laila, was in Mazar-e-Sharif Airport, trying to get out of Afghanistan. She needed to be quick: Two months earlier, the Taliban had regained power, and airports across the country were shutting down. Laila was sick; she had just tested positive for COVID-19 and needed to breathe from an oxygen tank that sat beside her wheelchair, like a sort of pet. It was Oct. 7, 2021, and my mother was leaving her beloved Afghanistan for the second time.

Initially, airport officers deemed her too high a risk, worried that her health would fail mid-air. But my sister and brother, who were also there with their families, pleaded with them, saying they would not hold the airline responsible if something bad happened to her. Finally, she was allowed to board, but without the unwieldy oxygen tank. She knew this would be difficult — without it, there was a chance she could stop breathing. After very little consideration, Laila ripped the tubes from her nose. “I go with my children,” she told them, defiant.

Eventually, the airport gates opened, and the passengers boarded a bus that took them to a plane headed for Qatar. From Doha, she would fly to Germany and then on to the United States, where more of us were waiting for her, including me and two more of my brothers. As the plane departed Afghanistan, we tracked its path online, desperately hoping that she would not go into respiratory arrest. This was the most stressful moment of our lives: watching a little lit pin on a screen, over three excruciating hours, not knowing if our matriarch was able to breathe or not.

At last, Laila landed in Doha, where she was rushed to a hospital. There, she spent the next two weeks before starting the next leg of her journey.

For Laila, this salvation was about more than her physical safety. Getting on that plane and out of Afghanistan had not been her only concern. My mother was more afraid that members of the Taliban would identify her and our family. We are of Hazara ethnicity and have been heavily discriminated against over many years. We have several relatives and friends who have been killed in suicide attacks aimed at them because they are from our Shiite minority.

For this 74-year-old grandmother, the Taliban are the epitome of violence and brutality.

The first time Laila left Afghanistan was in 1979, when she and her husband, Mohammad (my father), fled after members of the communist government killed his cousin. They went west, to Iran, where they lived out the decade of our country’s Soviet occupation. It was here that Laila’s eight children were born, including me. She has always tried to give us a better life than the one we were dealt. When our brother Reza was 9 years old, he was involved in a car accident that left him in a coma. Our mother nursed him every day, into his adulthood. She saw it as her duty to protect us from the dangers and violence that lurked around every corner, and she never wanted us to know what sacrifices she made for her children.

After Laila returned to Afghanistan in 2008, she was surprised by how her country had changed, how closed it had become for women. Even so, and despite being from the Hazara minority, Laila managed all sorts of feats, including becoming an extra in a Hollywood film shot in Afghanistan in 2010 (“Act of Dishonor”). In 2011, she worked with a U.S.-funded program in a village in her native Wardak province, helping women find work and achieve financial independence.

In 2020, she lost Mohammad, who was her biggest supporter. After a lifetime of his encouragement, she found herself suddenly alone. A year later, the Taliban swept to power.

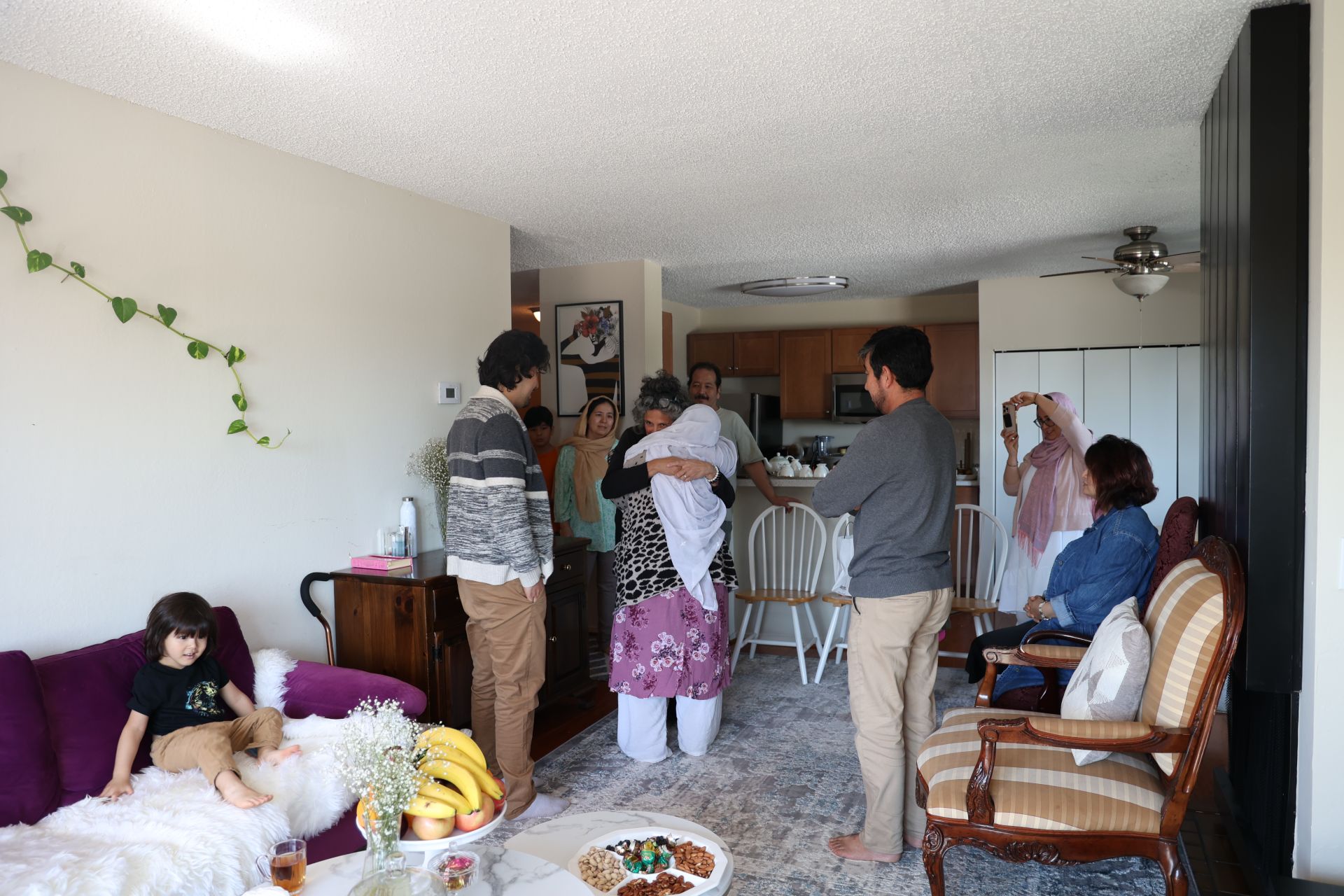

Now, she lives with her children in the United States, in Alexandria in Virginia, where there is a large Afghan community. She is continually amazed at the differences between life in Afghanistan and in America, and how many opportunities there are for women and girls: how they can study whatever they want, how they can choose their careers, how they can safely come home after dark. After she experienced a lifetime of discrimination for being Hazara, America seems to have equality — at least on the surface.

Of course, she misses Afghanistan, mostly the land itself. When she was a girl, she would help her father work their fields in the central Wardak province, where they grew wheat, potatoes, turnips and carrots. She is far from her siblings, relatives and friends, and it pains her knowing what Afghan women are having to endure under Taliban rule. Life is difficult at home for everyone, but women have no individual or social freedoms; they cannot go to work or study. Laila and her daughters are physically free, but she is constantly thinking of her sisters back home and how their lives are dominated by oppression.

Laila longs to see Reza, whom she believes has been transferred to Germany for treatment. My siblings and I decided we could not tell her the truth, that he had died shortly after she left Afghanistan. It would be simply unbearable for her.

For now, she is happy. Her children are artists, journalists and writers. We are thriving; we are safe. And we all owe our ability to think freely and creatively to our mother, whose hands are kind and whose heart cannot help but be warm.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.