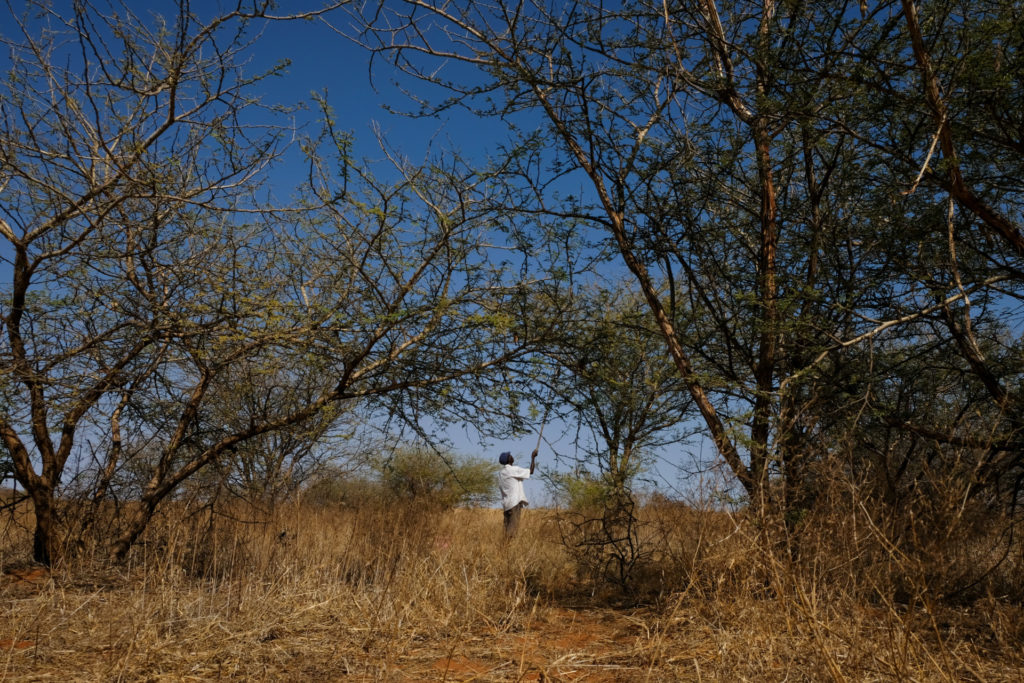

“Look up there,” the man says, pointing to a golden lump hanging from a branch. “See how the sap comes out of the tree?” Amin Al Hassan, now in his 40s, stands in the tree’s shade. Timna, his village, lies in one direction; more trees and bushes lie in the other direction, the vast and open lands of North Kordofan — a region in southern Sudan.

“We call this ‘the forest.’ These trees are very important to us,” says Al Hassan, poking at the golden lumps with his sonki, a long wooden stick with a metal peg attached to one end. When a lump falls, he catches it with his hand and drops it in a bucket by his feet. He repeats the procedure until he has emptied the tree of all these lumps and then walks over to another tree.

Al Hassan is collecting gum arabic: a golden sap extracted from the Acacia tree and a vital, almost magical ingredient in chocolate bars, chewing gums, soft drinks, cigars, medicines and more — from household brands like Coca-Cola and KitKat to prestige products like Havana cigars and unpronounceable pharmaceutical products.

Producers in Sudan, where the spiky Acacia tree thrives, make more gum arabic than those in any other country in the world. Harvesting in the winter, they also produce high-quality gum arabic — perhaps even better than others working in the so-called African gum belt, stretching from Senegal in the west to Somalia in the east.

“We are world-leading [producers]. We produce something like 79% of all gum arabic in the world. But not everyone knows its value,” explains Muneer Elyas, who heads the Institute of Gum Arabic Research and Desertification Studies at the University of Kordofan in the city of El-Obeid. He was sitting in his office, in a small building at the university, surrounded by an Acacia tree garden. On the wall behind him hung a painting of a woman harvesting gum Arabic from one of the trees. On his desk, too, were samples of powdered gum arabic and baobab — both nutritious and sold as supposed superfoods.

“Gum arabic is a very old crop here. We have known its benefits since historical times, when humans lived close to nature and ate from what they found around them,” Elyas explains.

Besides probiotic and pain-relieving properties, which locals have long valued, gum arabic has other important attributes that people and companies around the world need. It has thickening, stabilizing, emulsifying and glazing properties, making it an invaluable ingredient for a number of industries. It is used in sweets and drinks, sauces and chewing gum, vitamins and medicine — and for producing fireworks, cosmetics, paints and adhesives. Chocolate manufacturers need it so their bars don’t become greasy, snack producers for the salt to stick to their potato chips and beer brewers for the foam to sit on top of their drinks.

“No other ingredient can do what gum arabic does,” Mohammad Zarrag, an exporter of gum arabic, declares. “It cannot be replaced by anything else. People have tried but not succeeded.”

Zarrag’s company is the main supplier to Läkerol, a Swedish sugar-free candy made mainly from gum arabic. Many hard candies are up to 40%-50% gum arabic, with soft candies using about one third. During periods of shortage, the candy industry searched for alternatives to the ingredient but never succeeded. Läkerol produced a pastille without gum arabic during World War II named “War Läkerol.”

The soft drink industry is equally dependent on gum arabic, as it plays the crucial role of stopping the sugar in drinks from crystallizing. In 1997, when the United States imposed sanctions on Sudan, one single product was exempted: gum arabic.

“They never said it outright, but everyone knows that this was why,” Zarrag says.

The name gum arabic hails from a time when the commodity was exported through Arab ports like Alexandria and Jeddah. Indian gum, in contrast, came from Mumbai and was never as good quality. Long before it found its way overseas, gum arabic was used by the Egyptians for food, hieroglyphic paints and mummification ointments. In Europe, it came to be used for medieval manuscripts and medical treatments — later on, in the preindustrial era, it became essential for textile printing. Competition over gum was so fierce in the 18th century that outright “gum wars” were fought.

Today, the product provides an important livelihood in Kordofan and other parts of southern Sudan. Most families grow multiple crops including sesame, hibiscus and peanuts, but gum arabic is often their main source of income. In Timna, a 45-minute drive from the main road, few other job opportunities exist.

“Everyone in the village is involved in harvesting gum. We have done so for generations,” says Jenna Al Hassan, Amin’s wife.

Elyas notes that local farmers and people involved in the harvest don’t earn nearly as much as they should, or at least could. “Half of the global revenue should go to them, but it doesn’t. Even when the price of gum arabic goes up globally, it is not reflected locally.”

Sudanese producers may only capture between 4% and 5% of the value of processed gum, according to a 2018 report by the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development. Of course, intermediaries and local traders reap part of the benefit. But the big share ends up with companies abroad. While the export value of processed gum rose by 158% in the past 25 years, that of crude gum increased by only 58%. Half of the world’s gum is bought and processed by European firms, mainly in France. Indeed, a single French company, the family-owned Nexira, holds 50% of the global market for processed products. Other big players are Indian and Chinese companies.

People in Sudan, like others in the African gum belt, even import such products for their own industrial needs. “We buy glue in the store that is made from gum that was grown on our land,” Elyas says. His university works with farmers on innovation and financial strategies, like selling gum in large quantities to one buyer, thereby having more influence over the price. Otherwise, traders go to the villages and pay partly with goods like flour, sugar and medicine, a system that does not benefit the producers.

Across the city from the university in El-Obeid is a large industrial area. Sandy roads lead in between low-lying buildings, and tea sellers run their stands in the shade of large trees. A sweet smell of peanut hangs in the air: Many buildings house mills for grinding the ubiquitous nut (peanuts are called “Sudanese beans” in Arabic).

Inside one building is a large storage space, where golden lumps pile up to form small mountains on the floor. A group of women sit on jute sacks, cleaning and sorting the rough gum.

“We go through each pile several times to make sure there’s no dirt and rocks,” Hawa Mohammad, one of the women, explains. “Then we crush it into fine bits.”

She reached for a bag filled with gum and emptied it on a large metal tray punctuated with tiny holes. As she shook the plate, bits of dirt and stone fell on the floor. The process is repeated over and over, each time using a tray with smaller holes.

“Gum arabic is the hardest crop to work with, more tiring than peanuts and sesame. Your back and body aches,” says Hafsa Mohammad, Hawa’s sister.

The women are in their 40s and 50s, with at least one of them over 60. Their children often join the work on school holidays and breaks. The money earned is enough for food and housing, but nothing else.

Hussein El Khair, the manager on site, believes that “Sudan needs economic improvement. We need better education, better jobs and better working conditions.”

Sudanese producers may be on track. They still lead the world, by far: They tend to export about two-thirds of all gum arabic, and some 80% of all high-quality gum, in the world per year. Counterparts in Chad and Nigeria follow, with about 13% and 8% respectively in a given year. Sudan is also one of a few African states, alongside Nigeria and Senegal, with domestic processing capabilities.

In recent years, moreover, Sudanese companies have begun marketing gum arabic as a superfood, which they say boosts the immune system and helps with the absorption of vitamins and minerals. Locals have touted such benefits for a long time. During periods of drought, gum arabic served as a famine food. And people in Sudan still use pulverized gum as a remedy for ache, joint pain and stomach disorders. “We drink gum arabic mixed with water in the morning before breakfast. It cleans the stomach and prepares you for the day,” says Awad Haroun, a man from a village near Timna.

Others have used it to learn the word of God. Elyas described how, as a child, he learned to recite the Quran on traditional wooden boards, writing with a mixture of charcoal and gum arabic. “We rinsed it off with water and then drank it. They say that the spiritual wisdom of the Quran enters your body and protects it that way.”

His institute does extensive research on the Acacia tree, which plays an important role as a mitigator of climate change and a buffer against desertification. The tree reduces erosion and keeps water in the ground — the gum it produces, usually 2 to 3 kilograms (4.5 to 6.5 pounds) per year, sometimes as much as 10, is an added benefit. Acacia senegal, the kind that grows in Sudan, is known for yielding gum of the best quality.

“No one can compete with us in Africa. We produce big quantities, and our gum is the best,” says Tareq Al Barjawi, a trader in Rahad near El-Obeid.

Al Barjawi sells his gum to exporting companies in El-Obeid and the capital. Until Sudan joined the WTO in 2009, the government had a monopoly on the trade. Today, there are around five to six major exporters. Sudan would benefit from taking more control over the final processing of the gum, which is the most lucrative stage. While the country’s crude gum exports tripled in the past 25 years, from 35,000 tonnes in the early 1990s to 102,000 tonnes between 2014 and 2016, it makes up a small portion, some $200 million, of the total $4 billion exports.

Ibrahim Elbadawi, Sudan’s finance minister, recently mentioned gum arabic as part of a plan to address the economic crisis in the country. DAL Group, Sudan’s largest conglomerate, has started to process small quantities at their facilities in Khartoum.

“All steps can be done here in Sudan,” says Zarrag, the trader. “The challenge is trust in local companies and their ability to enter the global market.”

In Timna, some 500 kilometers (310 miles) from Khartoum, Al Hassan has filled his bucket with rough gum. He walks over to a large tree, where two donkeys wait in the shade. A 50-kilogram (110-pound) sack lays on the ground. Al Hassan takes his bucket and empties the gum inside. Hamid, also carrying a bucket, comes walking from another direction. He sits down under the canopy, then starts scraping at the layer of gum stuck on the palms of his hands.

The sun beats down.

“We always go out during the warmest part of the day,” Hamid, another harvester, says. “That’s when the sun softens the gum. Otherwise, it won’t release from the tree.”

The men place wooden saddles, made by craftspeople in the village, on the animals’ backs, and hang the half-filled sack across the spine of the largest donkey. Then they sit up, prompt the animals to walk, and set off with a slow pace. They need half an hour or so to reach the village, though they have not traveled too far for the harvest today.

They will go farther, tomorrow, to a forested area in the other direction of Timna. In two weeks, they will return to these trees. That is how long it takes for the gum to seep out, from the thorny branches these men will tap for another golden harvest.