Listen to this story

Nine years have passed since the moment my life changed completely. My heart stopped when I saw police officers standing in front of the main gate of my university, pointing to the back of a van, saying, “Get inside.”

I stood shocked, paralyzed by the thought: Oh, my God … they are arresting me. Before I could absorb what was happening, they were attempting to force me in. I don’t remember saying anything before that moment. Terrified, I desperately looked to the university security officers with eyes full of tears. I begged them with my stare: I know you. I can deal with you. Please take me to your room, interrogate me, and threaten me with whatever you want. … I don’t know these people, where they will take me or what they will do to me; please will you take me, not them. I knew that my silent appeals would fail; they tried to push me toward the police officers and the van. The reality of what was happening started to dawn on me.

I screamed as loudly as possible, hoping my words would find someone. My eyes were so full of tears that I couldn’t see clearly, but still I was shouting: “My name is Shaimaa Elhadidy. I am a second-year media student in the literature department. If something bad happens to me, you know who is responsible.” I pointed to the police officers waiting for me. I repeated this phrase three or four times, then stopped when I finally saw a student standing a few yards away. Our eyes met, and I stopped crying. I committed that anonymous colleague’s face to memory, thinking it would be the last friendly face that I would ever see. His nod showing that he heard me was enough to make me calm down and get into the police van. I was sure my family would know what had happened to me and that I would not disappear into the prison system without any official record of my arrest. Since the summer of 2013, we had heard about people disappearing with no trace after political activity. At least I wouldn’t be one of them.

I was arrested on Dec. 2, 2013. I was detained for four days and then released, and I still suffer from terrible memories. Yet I consider myself lucky. I’m free, unlike the hundreds of Egyptians who were arrested around the same time and have never been released. They have been deprived of their normal lives and experience torture, deprivations, and physical and psychological harm at the hands of an inhumane prison system.

The police officers took away my phone and put me in a steel cage for about 30 minutes before escorting me to the chief detective’s office. My “crime” was that I had been involved in protests calling for the release of other students who were put in jail for political activity. The chief detective threatened me directly by saying that I would receive “special treatment” in jail. He also conveyed the university president’s threat: to give me a “pinch” but nothing more, to stop my activism and to be a lesson for any other student expressing their opinions.

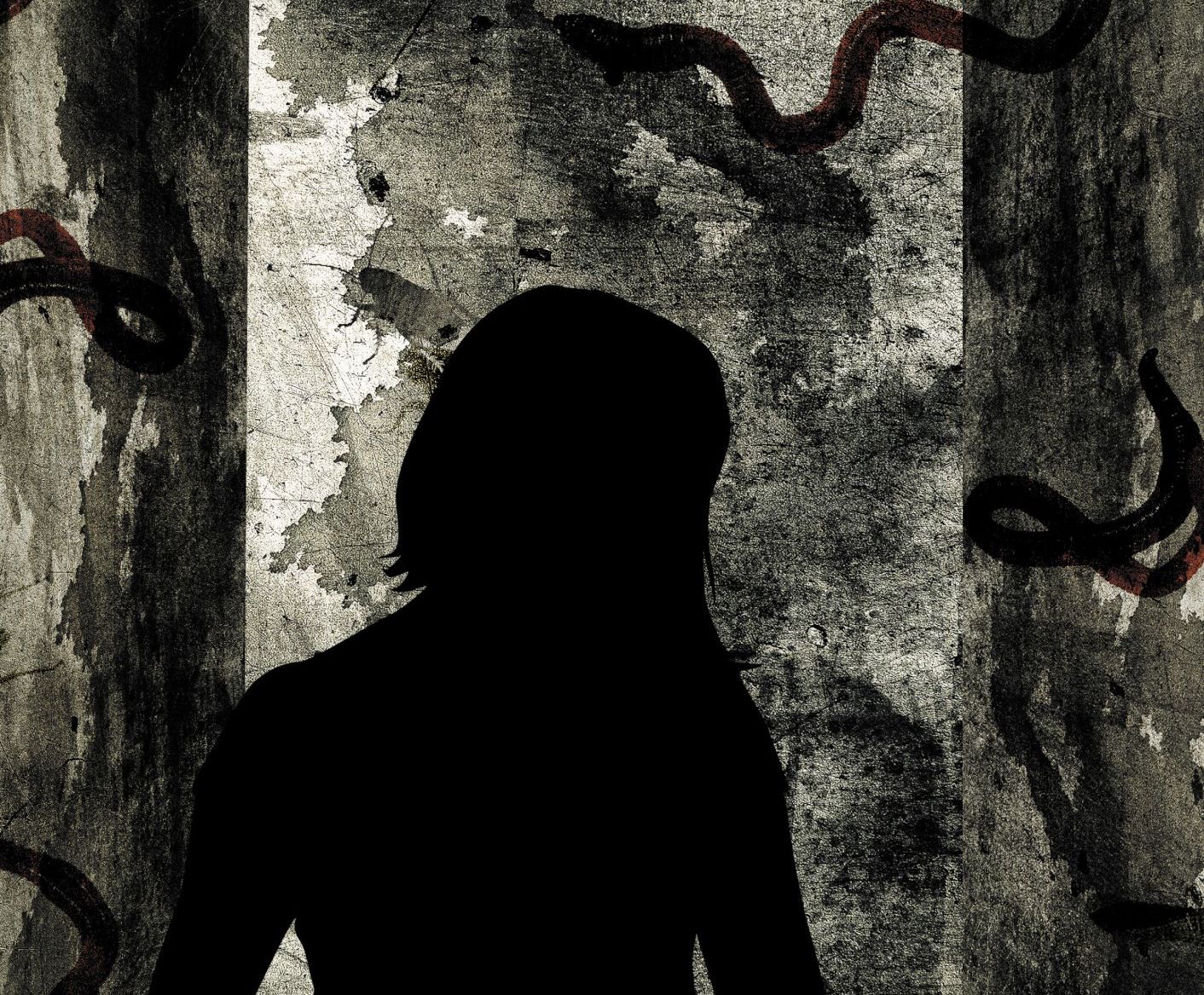

I spent my days in jail sleeping on a rotten floor, the room empty except for the darkness, the disgusting smell, bugs, humidity and moldy walls. The worst night was the first one; I was trying to calm myself, thinking that I had been trying to do some good for my imprisoned colleagues and that surely now someone else would demand that I was freed.

I had hardly adapted to this empty room before the guards came, around midnight, and asked me and another prisoner to go with him to a new location. I slept the rest of that awful night on a bathroom floor. A prison bathroom sees dozens of prisoners daily without cleaning or servicing, and here I put my head on a floor wet with prisoners’ waste and watched the bugs crawling around and the worms on the wall.

I was terrified of being harassed or raped. That’s the only thing I understood about the threat of “special treatment” — it was a mysterious and frightening threat. I didn’t want to face what some of the other female prisoners faced. I spent all day and night wearing all of my clothes, scared of the guards peeking through the window or suddenly opening the cell’s door. The most frightening moment each day was when I went to the bathroom: first, I would listen for the voices outside the cell to make sure there weren’t guards peeking, and then I would rush through the process, holding the door with one hand, and my clothes with the other hand. I didn’t shower during the four days of sleeping on the rotten floors; I used only a tap close to the floor to wash my hands and perform ablutions.

My situation eventually changed after four days, when my fate became known. The imprisonment of a young woman — me — studying at my university, in a conservative city, angered the students and they demonstrated more than once. This was the first time I had felt that being a woman conferred an advantage. Just as quickly as I had been arrested, I returned to the life I had known.

During my brief time in prison I went to and from the prosecutor’s office four times, escorted through the streets in metal handcuffs. I was threatened again, as I had been in the chief detective’s office, with spending 20 or 25 years in a cell, away from my family, friends and the world I had known. I believe I was the only young woman in the whole prison. I remember the first time I entered the prosecution’s building with an officer, in handcuffs. All the prisoners waiting for their cases stared at me as they smoked their cigarettes.

At the time, I was wearing a niqab, the face covering favored by some Muslim women, and the officers asked me to remove it in order to take some photos before releasing me. When I asked to be with only the photographer since I was wearing it for religious reasons, they refused and asked me to obey their instructions silently if I wanted them to complete the release procedure.

When the officer unlocked my metal handcuffs, I immediately ran toward my waiting friends and family. I screamed. I danced. I hugged everyone as if I hadn’t seen them in an eternity.

My joy was shattered by the sound of breaking glass, as hired henchmen who weren’t from our local area arrived at my home, throwing rocks through our windows. Dozens of police officers also arrived shortly after we left the prison and arrested my father, my oldest brother Ahmed, and my cousin, a lawyer. I saw my mom faint that day, and for weeks I watched my family going in and out of the courts in metal handcuffs, as the state now targeted my family.

I also received the news that I was prohibited from entering my university for a month. That decision was made while I was inside the jail, and I was the last to learn of it. In the following weeks, I saw my family released. But I also saw Ahmed fired from his job with an engineering company, just because he was imprisoned. I was eventually expelled from my university and barred from sitting exams for an entire semester. I received even more bitter news. Less than two months after I was released, the case was reopened. I learned that I was the subject of another investigation alongside 17 other students, most of whom were arrested at the university during my time in jail.

I lived for weeks in constant fear of arrest and avoided Egyptian security. I stayed with different relatives and friends, completely losing my sense of stability and my usual means of communication. My father secured some money and bought an apartment in another governorate. I lived there for nine months to have some peace of mind, and paid the price of being separated from my entire life — my mother, siblings, family, friends, university and colleagues. But at least I could see the sky, smell the fresh air and watch people from the balcony. I convinced my worried dad to let me walk along the city’s fascinating coast to escape the stress of isolation that was bringing on depression and suicidal thoughts.

Hundreds of other students were arrested for expressing their political views after the coup in July 2013.

In the last demonstration I participated in later that year, I was calling for the freedom of our colleagues, carrying a banner with an image of Adel, one of those detained who would go on to spend the entirety of his 20s between four walls (Adel is the pseudonym of a friend who remains in prison, and his identity has been withheld to protect him and his family against government reprisal). I could have easily been like him.

Despite what I went through at the age of 19, when I look back on the last nine years I consider myself lucky to be free. I endured nine months of prolonged hardship before I left Egypt. I was sentenced to six years in prison: a two-year prison sentence and a fine in the first case, and a four-year sentence in the second. But by the end of 2014 I was engaged to a friend I loved, and I was able to flee Egypt because the airport authority had not yet been informed of my sentences. I took a plane for the first time in my life and arrived in Sudan, where we got married. Although it was a wedding without my mom, siblings, relatives or friends, at least I wore a white dress.

Not lost on me was the fact that when I was fleeing Egypt, Adel was sitting in a cell with dozens of other prisoners without enough room to put his head on the floor to sleep. In the past nine years, Adel has rarely seen the sun, much less flown or fallen in love. He has had no occasion to celebrate or dance at a wedding. He probably doesn’t know any of the songs released in the last nine years. And I’m not sure if he even heard that two of his university colleagues were getting married abroad.

If I were still in jail, I would not have learned how to face obstacles like managing household chores in the country to which I fled, without the most basic infrastructure. I learned how to live without electricity, and water for 12 hours a day and how to transfer water from a well underneath our house to the third floor, to prepare food in unbearable heat. My experience wasn’t easy, but it was easier than sleeping on the ground for nine years like Adel. I had the luxury of complaining about not having air conditioning or a fan.

If I were still in jail, I would not have been able to learn more about journalism and editing. I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to work two jobs, with morning and night shifts online, saving money to move and complete my education.

If I were still in jail, I would not have tried so many times to get a visa to go to Turkey — only to come back empty-handed. (This was due to the strict regulations of the Turkish Embassy in Sudan concerning visas for Egyptians, as the employees at the embassy told us). Likewise, if I were still a prisoner, I wouldn’t have traveled to northern Cyprus to apply to a university and acquire residency documents for a Turkish visa, while working my remote jobs.

I was luckier than Adel and more than 2,500 other students who were in prison in 2018. In Turkey, I could start working in an office in an Arabic-speaking institution, learn some limited Turkish to help accomplish the basic tasks of life in a foreign country and touch snow for the first time. I could also look for a university to finish my studies alongside my office job. If I were Adel, I wouldn’t have spoken English for the first time in my life trying to explain the pharaohs and ancient Egypt to new colleagues. Despite all the workload and stress, I was only 22 years old and felt my life was progressing professionally and academically. Meanwhile, Adel was still struggling to get permission to complete his studies in prison.

Adel has remained inside that crowded prison for the past nine years, eating terrible food once a day and experiencing no privacy. He studied the physical sciences and memorized the Quran. He hoped to study for a master’s degree, but the universities would not accept an imprisoned student. Adel spent the rest of these years staring at his cell walls while I was free, seeing the world.

During the first five years of Adel’s imprisonment, his mother visited him once a week. She had to travel for hours to Abu Zaabal prison, where she was searched and humiliated and was then only able to see him for a few minutes from behind a screen. Adel said that he was subjected to torture and ill-treatment, but he shared little to avoid worrying his family. The same treatment continued when he was moved to Tora Liman prison. His family was grateful for his situation in spite of all of these tragedies.

“There are many other prisoners who could not finish their studies or don’t have anyone to support their families financially. … Their condition is more complex and more tragic than Adel’s,” his brother said.

In September 2018, I was struggling because of a decision to separate from my partner. I was divorced and miserable. I asked God frequently about the purpose of life, so full of struggles, and I wanted it to end. But honestly, I am thankful to God for helping me endure these feelings, which taught me a lot and influenced who I am now. While I was thinking about my disappointment and wishing to die, Adel was more disappointed but did not wish for death. He thought a lot about being in a relationship and getting engaged through his family, but he did not want to destroy someone else’s life, especially after what happened to him.

Also that month, Adel received a death sentence along with more than 70 others, in a case known as the “Rabaa sit-in dispersal” (Rabaa al-Adawiya is the square where Adel was arrested with hundreds of other demonstrators protesting the coup and where Egyptian security forces killed more than 800 people on Aug. 14, 2013, according to Human Rights Watch).

I can’t imagine Adel’s feelings during that period or those of his family who were unable to visit him for months. The rules of family visitation changed after he was sentenced to death; he was transferred to Gamasa prison and put in solitary confinement wearing red execution clothes. On top of everything, his cell was behind execution cells and torture rooms. Every night he could hear the screams of detainees who were being tortured or executed. Adel lived in a solitary cell for three years. During this period, his family was allowed to visit him once a month. His health and mental condition were worse each time, mainly because he no longer ate or drank due to his traumatic experiences in solitary confinement. With the onset of the COVID pandemic, the family was again prevented from visiting. Even after the visits restarted, they couldn’t see him. Adel was transferred to the hospital and lived on a medicinal solution for a while. His family only learned this when his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment instead of the death penalty.

In the meantime, I had a further struggle to renew my expired Egyptian passport as an exiled ex-prisoner and journalist. Still, the many attempts over about two years taught me how to be determined and not broken, even if I was a person without an identity and threatened with deportation, and therefore imprisonment, in my home country. Looking back, I’m thankful for these struggles and my good luck. I finished my studies in journalism and had opportunities to improve my CV in comparison with my colleagues by working in about 10 different workplaces and taking more than 25 specialized courses.

I have a car and a bicycle I bought with money from my work. I learned swimming and kickboxing. To fill my loneliness after the divorce, I tried to raise a cat and a golden retriever dog. I called the dog “Basit,” which means “simple,” because my feelings of fear were increasing. I discovered I’m a workaholic and can’t care for another soul. I cut my hair five times — one was a boy’s haircut — and I entirely changed my wardrobe around nine times. I also visited three other countries; I tried rafting, diving, parachuting, skating, taking a cable car and riding horses. I experienced the taste of sushi and octopus as well as Moroccan, Indian and Iranian cuisines. My thoughts and internal monologues have changed in a way that makes me feel like I’m several people who have the same name. I have moved into nine different apartments in the past nine years, and changed my laptop twice and phone three times.

Although I am happy with everything I have achieved, I am beset by “survivor’s guilt,” a concept I did not understand until recently. I figured out why I slept on the floor for about a year, from December 2013 (after my release) to January 2015. I took this decision because I felt that, in contrast to Adel and all my other prison colleagues, I had a comfortable bed to sleep on and a warm blanket to cover myself with. I could at least share one of their hardships if I slept like them. I think the only thing that made me stop was getting married, and then of course, I had to share a semi-normal life with my partner and sleep on a bed like most people.

For years afterward in Turkey, I didn’t notice that people were spending their weekends in fancy restaurants, walking in parks or going to gyms; I was only interested in working and my duties in life. I felt ashamed when I had to write entertainment features for a while, during which I composed what I considered to be useless essays and news. I was timid about sharing photos of leisure time with friends on Instagram.

Whenever I felt down, I blamed myself for not appreciating the gifts I had in my life, like freedom and being safe. I feel lucky, because if I weren’t, I would be like my colleagues, living in a cell inside a prison.

When I noticed this survivor’s guilt, I decided not to expose myself too much to news of those imprisoned. Sometimes I could stop myself, though at times I couldn’t, like now with Alaa Abdel Fattah’s hunger strike. I’m a journalist who needs to follow the updates, but I also feel a bond with their suffering. Every time I learn any new detail about Abdel Fattah, I imagine him sitting in my prison cell, leaning his back on the same wall I used to sleep beside so I could see the cell’s door when it opened suddenly. But I see him weakened as he contemplates his fate. I hope that he will soon be released. I think about the time he would need to heal in body and spirit as he returns to everyday life.

Adel had his 31st birthday last June. His last nine birthdays have been part of his prison life: beatings and insults and brief visits with his family. He can’t make plans for their future or the present. I sometimes wonder if he could live between those walls for a quarter of a century, or how he could live after he is released in a world that changes so fast. Even though he was a very sociable person, for the last nine years he hasn’t been able to hang out with his friends or care for his family. Adel hasn’t known what it is like to travel from one country to another, to talk to people from other cultures, learn new skills like diving, enjoy the taste of sushi, smell the warm air or feel the sun. He hasn’t been able to follow social media to learn about Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s relationship, Adele’s interview with Oprah, the inaugurations of presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden, or the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

I fear the tremendous gap between the world he left before his prison years and today’s world. We were all isolated during the pandemic, but for our health. We had luxuries in our isolation, even though some of us had issues dealing with everyday life afterward. Imagine isolating someone who knows that the world is moving on so fast while he is still stuck in time. “He was always asking about his family and the situation in Egypt, but now what he is asking about is if there is a way to be out of prison and see the outside world,” his brother said sadly.

When I asked him what his brother knew about the outside world after nine years, he said: “He lost his sense of time.”

This article was published in the Spring 2023 issue of New Lines’ print edition.