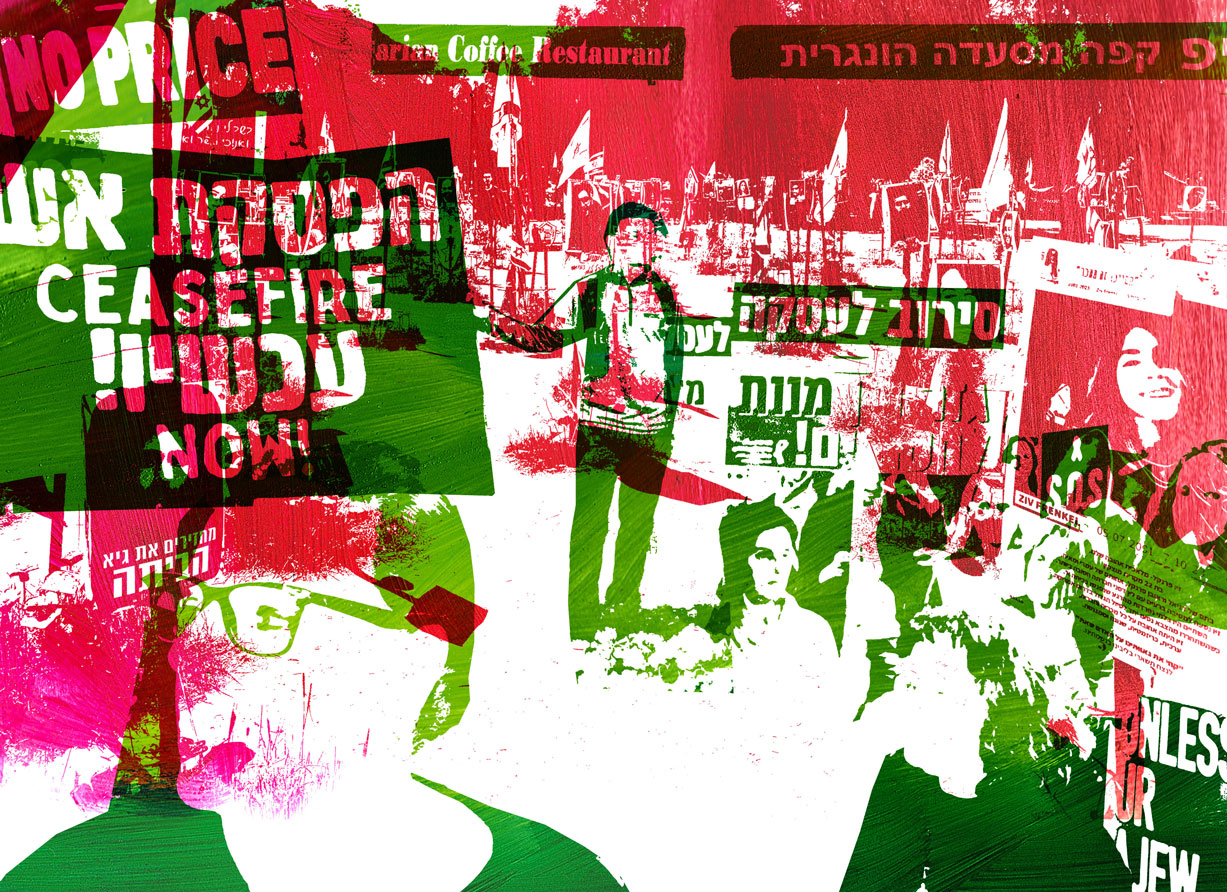

The war in Gaza was approaching its sixth month as thousands of Israelis gathered on a balmy Saturday night in front of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art for yet another anti-government protest. Their demand, which the liberal opposition had been making with increasing desperation since the military assault on Gaza began on Oct. 8 last year, was for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to agree to a cease-fire and negotiate a deal for the release of the hostages. Netanyahu’s justification for refusing to make the deal was that it would preclude “total victory” over Hamas. But for the opposition, most of whom had, before the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, organized and participated in weekly mass demonstrations against his far-right government’s plan to end the judiciary’s independence, the justification was an excuse; the prime minister’s real motivation, they believed, was to remain in power and avoid going to jail on the indictments for criminal corruption that had been hanging over his head for more than four years. By the time I arrived in Israel in March, the atmosphere at those demonstrations was one of agonized fear and powerlessness.

From an enormous stage equipped with professional amplifiers and projection screens, former captives who had been released in November and relatives of people still in Hamas’ hands addressed the sea of people standing below, many holding enlarged photos of various hostages. Thanks to their families’ efforts at humanizing them with details about their personalities and lives, many of the hostages felt deeply relatable and had become household names. A significant number of protesters wore black T-shirts and yellow rubber bracelets bearing the ubiquitous slogan “Bring them home now!” Many also wore “diskits,” the rectangular metal ID tags that soldiers wear around their necks; but instead of a name and serial number they were engraved with the Hebrew words, “Our heart is imprisoned in Gaza” or “We will dance again.” Some carried small bouquets of yellow tulips, their stems wrapped in brown florist’s paper. Israeli flags, the same oversized banners of blue and white fabric that protesters had carried a year earlier to the rallies against the far right’s judicial reform plan, were everywhere. Near the stage, a stand run by volunteers had been set up; here one could purchase the yellow rubber bracelets, the T-shirts and the diskits. The profits went toward the cost of mounting the protests and to the families of the hostages. When the speeches began, everyone listened intently and responded emotionally with chants of “Bring them home! Now!”

“I feel that we are begging for the lives of our loved ones,” said Raz Ben Ami, who was freed after 45 days in captivity. “I don’t sleep at night, knowing my [husband] Ohad is still there. I know how it is there [in the tunnels]. There’s no air, no light.” Aviva Segal, another former captive, whose husband Keith was still in Gaza, said, “I am asking the prime minister, what are you doing? I am dying inside! My heart is broken into pieces. Families here are choking with fear. And where are you? What are you doing?!” Shira Albag, mother of Liri Albag, a 19-year-old female soldier who was a “tatzpitanit” (lookout) at the Nahal Oz army base, read out the number of hours her daughter had been a captive in Gaza. Then she erupted in a primal wail of agony that made the base of my skull prickle. “I cannot stop hearing Liri scream the words ‘Mooooooom! Mom! Mom, help me! Mom!’”

The middle-aged female volunteer at the stand selling T-shirts and yellow rubber bracelets was just about to hand me the change for my purchase when she heard Shira Albag scream; she froze and a shudder worked its way through her body. I had never seen anything like this and flinched in shock. After a few seconds she stopped shuddering, handed me my change as though nothing had happened and went back to folding T-shirts. I heard a man standing nearby, wearing a “Free them now!” T-shirt, say to his wife, “Nu, should we go have something to eat?”

My friend Dahlia Scheindlin had warned me before my visit that people were having extreme, spontaneous emotional reactions to the aftermath of Oct. 7; she described an encounter of her own that was much like the one I had just witnessed. I would see many iterations of this ongoing trauma during my three-week visit. Six months after the event, Israelis were not remembering Oct. 7; they were still living it.

That same evening, while searching for a friend inside the museum, I wandered into a white-walled gallery that was hosting a performance of baroque music. About 30 people sat on blond oak benches listening appreciatively to a countertenor singing works by Henry Purcell and Giulio Caccini, while an accompanist played the lute. The hushed, pristine gallery, just steps from the raucous demonstration, encapsulated everything about the time I spent in Israel-Palestine, where everyone seemed to be simultaneously wrapped in grief and anxiety while pursuing pleasure and normalcy in an obsessive, often frenetic manner.

I gathered most of my initial impressions of this grief mixed with hedonism at Tel Aviv’s cafes, where the city’s residents famously — or infamously, depending on whom you ask — spend much of their time. Every conversation was intense and all of them were about the war and the political situation. One friend, a well-known peace activist, sat with her hands wrapped around a mug of cinnamon-orange tea as she described her experience of Oct. 7; suddenly, her voice caught and tears rolled down as she sobbed that she’d had a recurring nightmare since that day, about hiding her children in a closet to save them from being killed by Hamas — even though her children were already adults. Neither of us needed to say aloud what her nightmare implied about Holocaust associations and transgenerational trauma. Another friend, whom I met for early morning cappuccinos at an outdoor cafe near Dizengoff Square, greeted me with the words “Welcome to the madhouse,” and worried over his child’s imminent military conscription during wartime. They had agreed, he said, that they would not serve in a combat unit. On the way back to my apartment after that meeting, I ran into another friend, someone associated with the intellectual left. She was walking with her shoulders hunched forward, a worried furrow between her eyebrows. How are you? I asked. “Worried and uncomfortable all the time about what’s going on in Gaza,” she answered, looking at me sadly. “The mass famine, the mass killings. And I don’t know what to do about any of it.” We agreed we should meet for lunch, with her stipulating that we must choose a place near her home; since Oct. 7, she was afraid to be separated from her children for long.

But while dread and uncertainty were pervasive and cut across political lines in post-Oct. 7 Israel, almost no one within what one might call the Jewish mainstream criticized the army’s conduct in Gaza or mentioned the horrifically high number of Palestinian casualties, which human rights organizations were then estimating at around 35,000. This was partly due to the total absence of reporting about Palestinians in Gaza from Israeli news outlets. After months of following the international media’s coverage online, the silence of the Israeli media was so complete that it made my ears ring.

Most Israelis speak English and everyone has access to the internet, so not knowing about the tens of thousands of dead and wounded, the hundreds of thousands of displaced people living in tents, the orphaned and maimed children, the destroyed infrastructure, the barely functioning hospitals, the lack of humanitarian aid, the spread of famine and disease — that was a choice. People did not want to know. The commercial networks understood this, so they chose not to report on the death and destruction in Gaza and instead provided grief porn on an endless loop: interviews with freed hostages, with the families of people still in captivity, with bereaved families; interviews with wounded soldiers and heroic reservists whose wives were coping alone with the children while they fought for months at a time in Gaza; reports about the high cost of traveling abroad during wartime, with most airlines canceling their Tel Aviv routes; and solemn warnings about the rise of antisemitism abroad, which, according to a March 26 poll conducted by Channel 12, was cited by more than 36% of Israelis as their reason for forgoing a Passover vacation in Europe. Being forced into acknowledging the suffering of Palestinians under Israeli bombardment just an hour’s drive from Tel Aviv would have felt like a splash of icy water on the communally shared rage and grief. It was easier and oddly comforting to gather around the nightly news broadcast as though it were a tribal campfire.

I’ve lived through and reported on several rounds of conflict in Israel and was accustomed to seeing the entire country line up to support each war. Polls that showed more than 90% of Jewish Israelis supporting any given war were the norm. To paraphrase a popular Hebrew saying, the time for criticism is after the shooting stops. The space to question wars in real time had always been limited, but it existed. Now this was no longer the case. Outside the very small space occupied by far-left activists, expressing opposition to the war on ethical grounds was outside the bounds of acceptable discourse. In the minds of most Israelis, Gaza had barely existed on Oct. 6. The amazingly reductive popular narrative held that the Palestinian territory had been an independent, self-governing entity — when in fact Israel controlled Gaza’s borders, currency, population registry and airspace and had carried out three major military operations since 2008, each with high casualties — and then, one day, its residents, motivated by nothing but old-fashioned Jew-hatred, decided to massacre Israelis.

As far as Itamar Ben-Gvir, the far-right minister of national security, was concerned, dissent was illegal. On his orders, police were arresting Palestinian citizens and Jewish leftist activists for the most minor expressions of opposition to the war, like posting an olive branch and a prayer for peace on one’s Facebook page. This didn’t stop Jewish antioccupation activists from demonstrating every week in Tel Aviv, waving red flags and calling for “peace, equality, social justice — and revolution.” (Palestinian citizens rarely joined the demonstrations, which is something else to unpack.) I’d been listening to the same people chant the same slogans for many years. I admired their values and their commitment, and many of them were my friends. But they were shouting into the wind.

There was an elephant-in-the-room silence about all this among beloved old friends who historically identified with the liberal left of the 1980s and 1990s, of Peace Now and Meretz, the far-left Zionist party that received so few votes in the last election that it didn’t cross the electoral threshold. This generation, for whom the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 was the defining event, were Israel’s traditional liberal elite — secular, highly educated, well traveled, fluent in English, culturally sophisticated. But their Achilles’ heel was their inability to recognize Palestinian collective rights, even as they believed strongly in the individual rights of all people, including Palestinians. Now they were feeling betrayed by Palestinians, convinced that most or perhaps all had celebrated Hamas’ brutal attack.

These Israeli liberals were locked in fear and grievance. After Oct. 7, they no longer felt safe in their own beds; they felt deeply misunderstood and unfairly criticized for what they saw as a justified and necessary response to Hamas’ bloody assault. There was no point in mentioning Israel’s 17-year closure of Gaza as context. This would immediately be interpreted as justification, which meant the conversation was over — and possibly also the friendship. So we avoided the subject because we were, I think, afraid of hearing an opinion we couldn’t bear from someone we loved and had on many occasions depended upon.

But there were no such reservations in passing encounters with acquaintances, old and new. While chatting with the stylish owner of a boutique that functioned as my retail therapy, she said, “After what they did on Oct. 7 there is no room in my heart for compassion. The army should just kill them all.” I said nothing, but she must have seen something in my expression because her warmth disappeared and she became brusque, quoting a price for the ring I’d tried on and turning away to rearrange some scarves. When I mentioned this encounter to a friend who works for a human rights organization, she shrugged wearily and told me that she and her staff had been sheltering in the stairwell of their office building during a recent Hamas rocket attack, when a woman from another office said, “They should just burn them all.”

A man standing outside the train station in Jerusalem preferred shooting to burning. Stacked on a table in front of him were T-shirts, posters, baseball caps and bumper stickers with the Hebrew words, in white letters against a red and black background, “You don’t put terrorists in jail. You execute them. A bullet in the head.” The slogan was illustrated with a hangman’s noose. I asked the merchant of death posters if I could take his photograph and he agreed readily. He even unfurled a poster and held it up for me to see. As I raised my iPhone camera, two girls in the dark-blue uniforms of an ultra-Orthodox school, the kind that teaches almost no secular subjects, conditions the girls to shun worldly matters and expects them to enter arranged marriages at the age of 18, looked at the man’s wares and pumped their fists approvingly. “You’re absolutely right!” they called out to him.

I was in Jerusalem on my way to Ramallah. The journey was always complicated and time-consuming because I don’t have a driver’s license, but now it was particularly fraught because most of the checkpoints had been closed since Oct. 8, so there were massive bottlenecks at the few that remained open. The solution was to hire a Palestinian driver from East Jerusalem; they were bilingual in Hebrew and Arabic, knew the back routes and, with their yellow Israeli license plates, could travel freely in, around and out of the occupied territories. But a driver was expensive: The round-trip journey from Jerusalem to Ramallah, a half-hour drive or a 9-shekel bus ride in better times, now cost me 700 shekels ($185). Saleh, a driver I’d hired in the past, was waiting outside the train station in his car. Soon we were bumping slowly along a narrow, badly paved West Bank secondary road. Every so often, a man wearing a yellow reflective vest would gesture for us to stop, lean in at the open window and mutter in Arabic, “Jaysh. Dir balak.” Army. Be careful. Saleh sighed and said that he’d never seen the situation this bad. He started reminiscing fondly about his youth in the 1980s, which he remembered as a time of freedom of movement and relaxed social contact between Jews and Arabs. I asked him how he’d been since Oct. 7. He stopped smiling and said, with a catch in his voice, “Where did all the hate come from, Lisa? Did they always hate us this much?”

My friend Samer (a pseudonym) opened the door to his modern, well-appointed Ramallah office. He was, as usual, immaculately dressed in loafers, a well-pressed dress shirt and a suit jacket, looking as though he was going for a Sunday afternoon stroll in Geneva instead of sitting in front of a television camera to deliver news updates for an international cable news program. It was Ramadan and the only Christian-run cafe in town had closed, so there was nowhere to meet and drink coffee during the day except his place of work. (“Are you fasting?” I asked. “I’m too secular to fast,” he laughed.) In the two decades I’d known Samer, I’d never heard him describe the impact of the occupation on his life. Now, he gestured to the view from his window and invited me to look at how rapidly the nearby settlement was expanding. The newest buildings were barely 200 yards from his office. Ramallah was being squeezed from all sides, he said, adding that if the settlement growth continued at its current pace he would, in a few years, no longer need a car, because there would be nowhere he could drive. He was already confined to his golden cage; after a recent near-death experience that involved a group of masked soldiers stopping his car on a main intercity road and pointing their loaded weapons at him (“I truly believed I was living my last moments”) he had decided not to leave Ramallah anymore, except to go abroad.

At some point during our conversation, I glanced at the television suspended behind Samer’s head. It was tuned to Al Jazeera, which was reporting around the clock from Gaza, and I flinched at what it was broadcasting: a video clip that showed two unarmed men walking on a dirt road, which was bordered on either side by enormous piles of rubble, the remains of apartment buildings that had been destroyed by aerial bombardments. Suddenly, one of the men lurched and flopped to the ground, then the other. A sniper had shot them dead. A moment later, a D9 bulldozer rolled into the frame and pushed the two corpses into what appeared to be a ditch. Samer looked at me, a concerned expression on his face. Was I all right? I pointed at the screen and asked, “Is that … real?” He swiveled around to look and confirmed it was real, adding that the clip had been playing on a loop for several hours.

Perhaps because I had looked away from the reporting coming out of Gaza for a couple of weeks while I was consumed with running around Tel Aviv interviewing people, I could not quite believe what I was seeing. Not for the first time in my years of covering Israel-Palestine, I doubted the Palestinian narrator — not because I believed he would lie, but because my brain could not process what I was seeing. Six months later, in September, The New York Times published a video report called “How a Single Family Was Shot Dead on a Street in Gaza.” The investigative journalists used open-source video to prove that Israeli forces had done the same to a family in Beit Lahia — killing them with sniper fire and then using a D9 to push their corpses into a ditch. I said to Samer that if this is what people were seeing on Al Jazeera all day for months, all that violence and suffering, it must have a neurological impact. Yes, he said calmly, of course. It’s just mass slaughter, I said. Yes, he said. Mass slaughter.

Samer was an old-fashioned Arab liberal. Secular, urbane, cosmopolitan, seemingly detached from political ideologies, he was always kind and warm. Everyone liked him. For years, he said, he’d told his Arab colleagues that they should really see Tel Aviv, that it was the cultured, secular city that represented a future for the Middle East, a place of cafes and intellectual conversations between people who were connected by ideas and interests rather than partisan ideology. “But I can’t tell them that anymore,” he said. I guess the hope for a meeting of minds between secular Jewish liberals from Tel Aviv and Palestinian liberals from Ramallah is over, I said. Yes, he answered. It’s over.

On the way back to Jerusalem, some young people on the road just outside Ramallah gestured at us to slow down — this time not to warn us about the army, but so they could give us bottles of water and little bags of dates, to break the Ramadan fast. They smiled and exchanged greetings with Saleh, exuding holiday joy and bonhomie. Saleh, who had been withdrawn since he asked me where the hate came from, perked up and said maybe we’d pass one of those roadside stands that sold delicious local strawberries. Then he turned to me and said, “When we get to the checkpoint, don’t say anything. Let me take care of it. We don’t want them to ask too many questions.”

Whether they were East Jerusalem residents, Palestinian Authority citizens in the occupied West Bank or Israeli citizens, all the Palestinians I talked to seemed to be gripped by a combination of sadness and betrayal. This was particularly true of the Palestinian citizens of Israel who had for years worked alongside Israeli Jews in professional environments. They were highly educated polyglots who had studied at Israel’s best universities, who spoke unaccented Hebrew and moved comfortably in Tel Aviv’s bar and club scenes. Now one of them told me that a work colleague he’d known for 13 years had said to his face that she had no room in her heart for the children of Gaza. Another could barely make eye contact with me when he said he was ashamed to admit that, for the first time in his life, he was afraid to express his political opinions to his leftist friends. They were all focused on their own trauma and grief. None was willing to listen to criticism of Israel’s military response. “I thought we were on the same page, man,” he said, his voice sounding a bit broken. There were exceptions to this sense of betrayal — friendships that had remained strong. But they were rare, and even then they were constantly tested by the tense, unequal situation in which they existed.

But the most distraught Palestinians I met in Israel were a family who had managed to escape Gaza after the war started, not because they were in a position to pay the prohibitive fees for a crossing permit to Egypt, but because they were Israeli citizens and, as such, had the legal right to live in Israel — although the Israeli authorities made realizing that right as difficult as possible. Sawsan (a pseudonym), 39 years old, was born in an Israeli hospital to a mother who had been born in Israel but married a Palestinian man from Gaza and raised her family there. All this was possible in the 1980s, when there was relative freedom of movement between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories. Sawsan married a Gazan man but her five children inherited her Israeli citizenship, which can be handed down for one generation; she registered each of her children for Israeli ID cards. After the war started, representatives of Gisha, an Israeli nongovernmental organization that protects the legal rights of Palestinians in Gaza, had to go to court to force the army and the Ministry of Interior to allow Sawsan, her children and a few dozen other women and children who had Israeli citizenship for similar reasons — i.e., they or their mothers were born in Israel and had married Gazan men — safe passage to Israel. But the authorities were not legally required to allow the husbands, who were ineligible for Israeli citizenship, to accompany their families. So the women had to leave them behind, not knowing when — or if — they would be reunited. Several women with Israeli citizenship had refused to leave Gaza for this reason. By contrast, Gazans with citizenship in any other country that could arrange their exit permits were entitled to bring their spouses.

Now Sawsan, after a harrowing journey through a war zone with her small children (“the worst days of my life,” she told me), weeks of postponed crossings at Rafah and 12 hours of Shin Bet interrogations, was staying with her children at the home of relatives in a village north of Haifa; she told Gisha that she would be willing to meet me there for an interview. Hatem (a pseudonym), a charismatic, multilingual, Jaffa-based activist and municipal politician, agreed to drive and translate for me.

Finding the village was quite a challenge. There were no signs on the main road. The army had jammed the GPS from Haifa northward, reportedly as a preventive tactic against Hezbollah, which was regularly launching missiles into northern Israel. The maps on our iPhones informed us that we were at Rafic Hariri International Airport in Beirut. We drove in circles until Hatem called his wife in Jaffa, who could access Waze from there; she sent us screenshots of the GPS directions via WhatsApp and guided us on speakerphone. Once in the village, we drove in circles again, because the streets had been given Hebrew names that none of the locals used so we couldn’t get proper directions. Entering a Palestinian village in the north of Israel feels a bit like traveling to a different country; unlike the planned Jewish-majority towns nearby, the villages have no sidewalks, no amenities like regular garbage collection, public swimming pools or municipal libraries. The billboards advertising Israeli brands of coffee and snacks were in Arabic. Finally, I told Hatem to tell Sawsan that we were near Mahmoud’s Travel Agency. Ah, she said. We live right across the street.

I expected a sad, shy woman wearing a dark jiljab, the voluminous dress and headscarf that so many Muslim women wear in conservative Gaza, and a roughly built multifamily home, like the ones I had visited in West Bank villages. But Sawsan was wearing a stylish tracksuit, her hair was freshly shampooed and her dark red lipstick matched her elegant manicure and pedicure. Her cousin’s house was new and modern, as though it had been inspired by an Ikea catalog, with large, airy rooms and a kitchen that I coveted. I felt quite scruffy after the long drive. Sawsan’s cousin, who was similarly stylish and meticulously groomed, offered me coffee. But Hatem was fasting for Ramadan and I couldn’t tell if Sawsan was also fasting — probably not, since she was breastfeeding, but I didn’t want to ask — so I said no. I wasn’t going to drink coffee alone while my caffeine-deprived hosts watched.

The interview was chaotic. Sawsan’s children were all, she told me, deeply disturbed after living for five months under bombardment. The youngest was only 15 months old and he cried constantly, demanding his mother’s attention and grabbing my iPhone, which I was using to record the conversation. Sawsan said she couldn’t leave the children alone for long and usually slept with them in the same bed because they woke up frequently during the night, screaming, which made it difficult to be a guest in her relatives’ home. The children needed therapy, she said.

The story that she told, in a very nonlinear fashion, with many noisy interruptions, was astonishing and heartbreaking. Before the war, she said, they had a very nice life in Gaza. In answer to my question she said yes, of course there were many poor people living in the refugee camps, but she and her family were not among them. Because she had an Israeli ID card, Sawsan was able to cross Erez Checkpoint and travel to Jaffa every few months, where she picked up shifts working on checkout at a supermarket. I asked if she spoke Hebrew. “Shwayeh,” she said. A little. Enough to get by; how much Hebrew did she need to scan food items and hand people their change? In 2021, her husband obtained a permit to work in Israel, under the auspices of an agreement the army brokered with Hamas to alleviate Gaza’s economic distress; his earnings for carpentry on construction sites put them solidly in the middle class (the husband was in Israel on Oct. 7 and fled to the West Bank; she hadn’t seen him since and my friend at Gisha told me they might never be reunited). The eldest of her five children was a 20-year-old woman, already married. The three younger ones, aged 15 months to 12 years, were with her. She also had an 18-year-old son who was trapped in Gaza. And that, I learned, was the reason she had agreed to the interview.

The son was engaged to the love of his life and refused to leave without his fiancee, Sawsan explained, adding that she had begged, screamed and pleaded with him for days. But the son was implacable. So she took the three younger children and made the harrowing journey from Khan Younis to Rafah, which involved paying a taxi driver the astronomical sum of 500 shekels ($130) for what would ordinarily have been a 20-minute drive. By comparison, the 20-minute taxi ride from Ben Gurion Airport to Tel Aviv cost me 150 shekels ($39). But gasoline was scarce in Gaza and the road was under constant fire from snipers, tank mortars and aerial bombardments, although the Israeli army had supposedly guaranteed them safe passage. Sawsan, her sister and their children, 17 people in all, arrived in Rafah one hour after a bombardment — there were bodies on the street, she said — and went directly to the crossing, only to be turned away by Egyptian officials who said their names were not on the list. So she had to find food and shelter in Rafah, which had become a tent city for those displaced from the north, and wait for a phone call from Gisha, which was dealing with the Israeli authorities on her behalf.

Later, my contact at Gisha told me the women were instructed so many times to present themselves at Rafah Crossing, often with less than an hour’s notice to pack up their things, gather their children and find transportation, only to be turned back, that they were convinced the authorities were toying with them and had no intention of allowing them to leave. Sawsan and the children lived in a tent for weeks. She ran out of money and had to beg for food. The cost of a pack of diapers rose to 200 shekels ($52), so she had to use old T-shirts for the baby.

Finally, they made it out through Rafah Crossing. There was a one-hour bus ride through the Sinai to the Taba Crossing into Israel — a ride for which she and the other Gazan women with Israeli citizenship had to pay $75 per person. At Taba, the hungry, exhausted, terrorized children were made to wait for 12 hours while Sawsan underwent interrogation. I asked: Did they at least feed the children? Only some bottled water and Bamba, she answered, referring to the peanut-flavored corn puffs that are the most popular snack in Israel. She also had to hand over 15,000 shekels ($3,930) for a DNA test to prove that her youngest son, whom she was still breastfeeding and had not had time to register with the Israeli authorities before the war, was actually hers. She knew in advance about the cost of the mandatory test and had raised the money from her extended family in Israel, she explained. Later I confirmed with Gisha that the authorities kept 5,000 shekels and returned 10,000, which they had held as a bond pending the results of the test.

An Arabic-speaking Shin Bet officer interrogated Sawsan in a separate room while her children were left alone in the waiting area with their water and snacks. What did the officer ask her, I wanted to know. Oh, she said, he yelled and threatened me. He said I would be stripped of my citizenship because my right to live in Israel had expired, so my children would be allowed in but I would be turned away. But I knew this was not true. They kept asking if my older children were affiliated with Hamas or if other members of my family were Hamas. The interrogator was not an Arabic-speaking Druze citizen of Israel, she insisted, in answer to my question. He was a Jewish Israeli and “he spoke better Arabic than me.” He couldn’t intimidate me, said Sawsan, who was clearly proud of being a bit of a badass. I know my rights, she said calmly. Finally, the DNA test results came back. The authorities returned the 10,000-shekel bond, kept 5,000 shekels and she was free to leave.

You must have been exhausted, I said. Yes, but I didn’t feel anything except relief, she said. The children, too. It was such a relief not to hear bombs and shooting.

Three weeks later, Sawsan’s son called and begged her to get him out of Gaza. He was living with his grandfather in a makeshift tent of nylon tarpaulins in Mawasi, near Rafah, after the army ordered residents of Khan Younis to evacuate to the south. He was terrified to go outside, convinced he would be shot — not an unreasonable fear, given the circumstances. He was hungry and isolated. Sawsan’s voice caught when she said her son was crying on the phone, at which point Hatem choked up and had to stop translating for a moment. But the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, the Israeli body charged with civil affairs in the occupied territories, refused to rearrange the son’s passage out of Gaza. He’d been given an opportunity to leave and turned it down, was their implicit message; now he was on his own. Sawsan was desperate. And this was why she had agreed to the interview. I thought, she said, that if my story were in the media, it would embarrass the Israelis and they’d get my son out.

As we drove away, I said to Hatem: She just lived through five months of bombardments. Her house has been destroyed, her life’s savings are gone, she’s separated from her husband by the war and might never see him again, she saw corpses on the road and tens of thousands of displaced people living in tent cities that the army bombarded after telling them it was a safe zone, the Israeli authorities made her pay 5,000 shekels for a genetic test to prove that her own son, whom she was breastfeeding and for whom she had a birth certificate, was actually hers — and she thinks she can shame them into allowing her son out? Hatem sat silently for a while as we drove. Then he said that her story sounded much worse in Arabic and he wished he could feel some hope for the future. As of this writing, Sawsan’s son is still in Gaza and Waze, the Israeli GPS platform, still insists that Haifa and the rest of Israel’s north are in Beirut’s Rafic Hariri International Airport.

The following evening, I told this story to friends over arak and lemonade at an inimitably cool Tel Aviv bar in a repurposed industrial space. If you wanted to meet up with your radical Israeli friends — the ones who went to jail for refusing military service and generally put themselves in harm’s way for their antioccupation and anti-racist principles — this was the place to hang. I recounted Sawsan’s story to Noam Shuster-Eliassi, who was famous for her standup comedy act, in which she used her fluent Arabic to skewer the Middle East’s racism and nationalism (an upcoming documentary film about her is called “Coexistence, My Ass!”). Also there were Edo Konrad, the former editor of +972 Magazine, and Sapir Slutzker-Amran, a social activist who, a few weeks later, was filmed trying to stop Kahanist youths from destroying food aid before it could be trucked into Gaza. Not for the first time, Sapir put her own body on the line; the hate-driven adolescents beat her. When I’d finished describing the events of that day up north, Noam said, “Isn’t it just crazy that we’re sitting here in this bar, listening to music and having drinks, while all this is happening to people just a short drive from here? It’s crazy!” I looked around, at the insouciant, cool bar patrons, pierced, tattooed and nonbinary, sitting on mismatched benches arranged around low tables bought at flea markets, as they filled rolling papers with loose tobacco, talked and laughed. If we could drive to Gaza, we would be there in 45 minutes.

It was Sapir who told me about the internally displaced Israelis from the north, whom the government was housing in cheap Tel Aviv hotels. One day after Hamas attacked the south on Oct. 7, Hezbollah unleashed missiles on the north. Continual intermittent bombing had since made the area unsafe and, for many, unlivable; the army said it wasn’t able to protect the residents and ordered them to leave. Six months later, around 60,000 people from the north were scattered around the country, housed in hotels that the state had commandeered for them. Often, entire families lived in a single room. Meals and accommodation were covered, but displaced people were still responsible for the rents and mortgage payments on the homes in which they were not permitted to live. No one could tell them when they would be allowed to return. Those who were without an income received a stipend, but if they practiced a profession that was not location-specific, they had to work.

This was the case for a middle-aged woman from a kibbutz near the border, who was living with her two daughters in a no-star hotel at the grubby southern end of Tel Aviv’s beachfront. She was a palliative social worker, she said, so the health care authorities had simply reassigned her to a hospital in the greater Tel Aviv area. She wouldn’t give her name, just her age (50), so I’ll call her Tali, but she was quite willing to talk when I stopped her in the lobby of the hotel, where I’d been sitting and accosting random residents for about half an hour. She turned to her two sad-looking teenage daughters, handed them the key to their room, and told them gently, “You go upstairs. I’m going to sit and talk with this nice lady.” Tali had a son in a sensitive military unit. (“Not in Gaza. I can’t say more, but it’s enough to keep me awake at night.”) Her two daughters, she said, were “not OK.” They’d been out of school for months, missed their friends, missed being at home and couldn’t deal with the upheaval and uncertainty. They were in therapy, she said.

Tali had bought a new house just before the war began (“the movers were scheduled for Oct. 20”) and was still paying the mortgage, though she had no idea when she could move in. Her husband was staying in a different city in Israel because it was closer to his work. In other words, Tali was living with a level of stress and uncertainty that I would have found unbearable. But she was very composed. She was slim and nicely dressed in clean jeans and a fresh-looking shirt. Her hair was pulled back neatly and her skin was smooth, except for the care lines around her eyes. When I asked why she had agreed to speak with me, Tali leaned forward and said intensely, emphasizing each word, “Because we are the victims. The world must know this. That is why I agreed to speak to you.” She leaned back and stared at me silently for a moment. Then she continued: “I don’t care about politics. Left, right … It’s all the same to me. I don’t care who the prime minister is. All I want is peace and quiet.”

But as our conversation continued, Tali revealed that she did have quite strong political opinions, although perhaps “worldview” is a more accurate word. Not for the first time, I heard a well-spoken and caring middle-class parent say she didn’t care what happened to the people in Gaza, not even the children. “They should all burn!” she said, then asked rhetorically: “Why don’t the Egyptians help them? Because no one wants them! They are murderers! Can you imagine if someone came and kidnapped children from your home? People need to know this. They need to know!”

So, I asked, what did she think was the solution? How should this war end? “I don’t know,” she said. “Maybe if we educate them. We need to educate them not to murder children.” She continued: “Once we were friends with people in Gaza. I grew up in Ashkelon and we used to drive there to buy pita. And on the kibbutz we had a gardener from Gaza who showed us the scars where Hamas had beaten him. He hated Hamas more than we did! So where did all the hate come from? I just don’t understand it. We didn’t start this war, they did. The Jews are a hunted people,” she said, using an expression in biblical Hebrew. “We will have to live by the sword.” Then she repeated that she was not political, so I asked if she watched television news. Sometimes, she said. Was there a channel she preferred? She paused, then named Channel 14, Israel’s far-right broadcaster, the equivalent of FOX News. “It relaxes me,” said Tali.

I left the hotel, heavy with thoughts about my conversation with Tali, and walked toward the Hassan Bek Mosque; Muslim families were having an Eid picnic in the park opposite. Nearby was the Carmel Market, a sprawling warren of narrow streets lined with shops selling all sorts of foodstuffs, with trendy cafes and hip restaurants tucked into repurposed storage spaces. It was Friday afternoon, a few hours before the workweek ended, when the shops closed, the municipal buses stopped running and the noisy city fell quiet for a blissful 25 hours. I loved the market, but for a person who tends to have minor meltdowns when subjected to noise and crowds, as I do, it was the wrong place to be on a Friday afternoon. And it was hot. I do not like the heat. The fruit and vegetable sellers were shouting hoarsely, extolling the quality and low prices of their wilting herbs and softening strawberries, anxious to sell them before they spoiled. Arabic and Hebrew pop music blared from portable speakers. Extra tables had been added to accommodate spillover patrons at the outdoor cafes, where millennials wearing tank tops and sunglasses greeted one another with palm slaps, bear hugs and kisses. Someone called my name. I swiveled around and saw a round-bellied bald man with green eyes and a big smile standing in a shop that sold Levantine specialties like labneh, olive oil and stuffed grape leaves. In Arabic-accented Hebrew, he said, “I knew it was you! I knew it! Walla, habibti, you used to buy from me every week and then you disappeared. It must be 12 years! Where have you been?”

I had no memory of this man. None. But he looked so happy and expectant that I simply did not have the heart to ask his name. Thank God a customer stopped by and called him by his name — Mustapha. So Mustapha launched immediately into a long soliloquy. It started with his cancer scare — he pulled up his stained white T-shirt to show me a long, thick abdominal scar, then assured me he’d been back at work within 10 days of the surgery. Did I want coffee? I hesitated, thinking of the three espressos I’d already drunk that morning. “Here, have some coffee! Arabic coffee, of course!” He poured some from a thermos. Oh, go on then. What was a little caffeine poisoning between friends? He told me about the race riots of May 2021, when he and his sons had defended their family compound in Lod (Lydda) from masked settlers armed with bats, while also sheltering their Jewish neighbors from Arab rioters. He pointed to fruit and vegetable stands nearby and said proudly that he’d set his sons up with businesses of their own.

After a half-hour or so, I was feeling a bit overwhelmed, so thought I’d extricate myself by buying things: a jar of shanklish, labneh balls, in olive oil; stuffed grape leaves; a bag of zaatar; hummus; the red pepper and walnut dip called matbuha; tahini; olive oil, the ur-artisanal kind from a small farm, poured into old cola bottles. I asked if the olive oil was from Hebron, which had the best olives. Mustapha shook his head. No, he said. It was too dangerous to go to Hebron these days, because of the violent settlers. He had driven up to Ghajar, a disputed Alawite village in the north that was claimed by Syria but de facto divided between Israel and Lebanon, with the residents on the Israel-controlled side holding Israeli ID cards. I said teasingly, “So you bought the oil in Lebanon, eh?” Before he could respond, the bearded proprietor of a fruit stand next door entered the shop to check his phone, which he’d left there to recharge. Mustapha introduced us and the man leaned in, so that the beak of his cap touched my forehead, and said, in a voice hoarse from shouting about his strawberries, “This man is a golden soul. A golden soul, I tell you! If all the Arabs were like this man, and not like the zbaala [the Arabic word for garbage] in Gaza, we wouldn’t have any problems in this country.”

I looked at Mustapha, who had hung an Israeli flag on the wall of his shop alongside a photo that showed him in the smiling embrace of Tel Aviv’s mayor, Ron Huldai, and saw that his smile had slipped a bit and frozen. I could only imagine how many of these little humiliations, these microaggressions, he must experience every day while he struggled to maintain collegial relationships and live his life in peace. He would never be allowed to forget that he was a second-class citizen in his country of birth. Mustapha handed me a bag heavy with the foods I’d chosen — I was leaving in two days and had no idea what I would do with it all — and pushed my money away. No, it’s a gift. Don’t insult me! Take it. After a long back and forth I capitulated, kissed him on each cheek, said goodbye and left. As I passed his son’s vegetable stand I said, “Your father is a very generous man.” The son answered: “I know.”

There was one more place to see before I left Israel-Palestine. On the penultimate day of my visit, I went down to Re’im, the site of the Nova dance festival massacre. Through a friend I’d hired a driver named Tal, a doctoral candidate at Tel Aviv University looking for side gigs to finance a film project. Soft-spoken and slightly built, Tal drove a battered red Subaru with a dusty dashboard and he arrived exactly on time, which turned out to be an auspicious beginning to a long day that was tiring and draining but, for a writer, professionally rewarding. As happens so often in Israel that it’s practically the norm, during the drive down Tal and I immediately slid into an easy, intimate and animated conversation. He was a music geek with a deep interest in an obscure Israeli punk rock band that he’d spent years following and then interviewing for a film project. We talked about his love life, his friendships, his family and his army service; he was so gentle and self-effacing that I was surprised to learn he had been an officer in a combat unit. He started out very gung ho, he said, but by the end of his service he hated the army and wished he hadn’t chosen a combat unit. He’d managed to get an exemption from reserve duty but now felt guilty that his friends were fighting in Gaza while he was safe in Tel Aviv.

As we approached Re’im, he mentioned that one of his students had been killed there and that he’d been to her funeral. We stopped talking when we saw the rubber tire marks still visible on the road, where drivers who had been shot on Oct. 7 lost control of their vehicles and skidded off. Finally, we rolled up to the site of the party. Tal parked the car and looked at me for instructions, asking how I wanted to handle this. Let’s just walk around, I said. As we approached the site of the massacre, we both realized that we had seen so many videos of that dreadful day that we could identify quite granular details. That was the tree where the girl hid and filmed herself while there was a man armed with a gun right below. There was the “migunit,” the concrete shelter where some partygoers were hiding until they were discovered and shot. Inside were memorial candles and graffiti — the names of the dead, the phrase “We will dance again” and the word “nekama,” vengeance. There was a new cemetery; I stopped counting the headstones at 200 and saw a man standing in front of one of them, his hand over his eyes. Gaza was just 2 miles away. I could see smoke rising and hear the buzz of the drones, the not-very-distant booms of tank ordnance and aerial bombardments. But no one looked up or even seemed to notice.

There was an ad hoc memorial, photos of people who had been killed on Oct. 7 printed on poster board and mounted on sticks that were planted on the ground in a cluster. Tal found the photo of his dead student; she was a beautiful blonde woman who looked like a model. Also at the scene was a busload of soldiers, who had been brought there to see what they were fighting for, and a Chabad “mitzvah-mobile,” a camper vehicle decorated with a photo of Rabbi Menahem Mendel Schneerson, their dead spiritual leader. Here, secular soldiers could stop at a folding table set up outside the camper and put on tefillin, or phylacteries, with the help of one of the proselytizing hasidim. I’d noticed a few luxury cars with diplomatic license plates in the dusty parking area and saw now that there were several foreign nationals walking around the place. The two I fixated on were a British soldier in uniform and an older man in civilian clothes, short and a bit stocky, who wore a canvas twill sun hat. The British soldier had a tight expression on his face and the two were speaking intensely. I strained to hear the soldier’s words as the wind pulled them away. “Two tours in Afghanistan … if … 35,000 dead … would have been … heads would have exploded … unbelievable.”

I am not, apparently, a person endowed with great subtlety; the two men noticed me eavesdropping, stopped talking and moved away. I followed them, introduced myself and asked if they were authorized to speak with the press. The older man in civilian clothes said briskly, “I am but he isn’t.” But when I asked if he would mind answering a few questions he shut down, telling me I should contact their embassy spokesperson. I persisted. “I wonder if you noticed that we can hear the booms from Gaza but no one is reacting,” I said. The soldier who was not authorized to speak to the press muttered angrily, while staring into the distance with his hands clasped behind his back, “Well, that’s really the whole story, isn’t it?”

As we drove away from Re’im, Tal asked me if I thought the war was justified, “after they killed 1,400 people.” I turned the question back on him. He thought for a bit and said slowly that he didn’t know, maybe the scope of the response was too much, but surely we did have to respond. We did, right? Then he suggested that we stop at an Indian restaurant in Beer Sheva — the owners were Bene Israel, Jews from India — and have a thali for lunch. It turned out to be a simple place with excellent, home-style food and we both felt better after we’d eaten.

Back at my place in Tel Aviv, I paid Tal, adding 200 shekels to the 600 we’d agreed upon, and made him even happier by giving him the bag of food for which Mustapha had refused payment. I had to be at the airport by 3 a.m., so I didn’t bother to sleep, just sat up late transcribing my notes from that long day and cleaning the apartment a friend had lent me. When my flight took off in the morning, I felt a rush of emotions — relief to leave the madness, grief for a place I loved and which I knew was headed for a very bleak future, fear for my friends. I looked forward to going home.

I am writing the final words of this article on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, which this year comes four days before the one-year anniversary of the Oct. 7 attacks. Rosh Hashanah is the beginning of a 10-day period called the Days of Awe that ends on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. During the 10 days, Jews traditionally engage in introspection and seek forgiveness from those whom they might have wronged during the previous year. In Montreal, where I live, I gather on these holy days with a community composed of cultural Jews for an abridged version of the traditional service that is led by lay volunteers. The point is community and the warmth of celebrating a shared identity, not religious faith. But even among this group of like-minded, liberal, creative people who live far from the Middle East, the war in Gaza has become a divisive issue, as it is in the wider Jewish community, within extended families, on college campuses, in academia, in politics and in international relations. We will all have to figure out a way to move forward without agreeing, because the situation in Israel-Palestine is not going to improve in the short to medium term. It will get worse before — if — it gets better. The future of this place is, as I wrote above, bleak and frightening, and I am not one to look for hope where it cannot be found. But as I read over this article and thought about all the personal encounters in Israel-Palestine that I simply ran out of time and space to write about, it occurred to me that, besides wanting the same things — a loving and happy family, satisfying work, prosperity, safety, peace and quiet — everyone I spoke to, even those who expressed racist, murderous views, remembered a happier time when Jews and Palestinians interacted amicably, like Tali from Ashkelon who reminisced about childhood trips to Gaza where her family bought pita, or Saleh from East Jerusalem who spoke nostalgically about the 1980s as a time of relaxed social contact between Palestinians and Jews, or Samer in Ramallah, who cherished an image of Tel Aviv as a place where Jewish and Arab intellectuals socialized and shared ideas. People do tend to find a perverse comfort in marinating in grief and grievance, largely because this eliminates the need to engage in reflection and contemplate complexity. I don’t know if looking up from our navels will help the people in Gaza, but it could help prevent the next Gaza.

Meanwhile, I look to the remarkable people I know in Israel-Palestine who are totally committed to political and social justice activism, who see the world through a lens of unswerving moral clarity, although they operate in an extremely challenging, increasingly dangerous environment, often at significant personal sacrifice. Leonard Cohen, the Montreal-born Jewish poet whose famous song “Who By Fire” was inspired by the liturgical poem about judgment day that is sung on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, wrote a song called “Anthem” for his 1992 album, “The Future.” The second verse of the song goes like this: “Yeah, the wars / They will be fought again / The holy dove / She will be caught again / Bought and sold / And bought again / The dove is never free,” followed by the chorus with the famous lines: “There is a crack, a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.” In these very dark times of extreme political violence, deep trauma and rising extremism, I look to the extraordinary, caring people I know and I see a crack of light.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.