Thirty years on, I still remember my brother clearly. From the time he became a teenager, I idolized him. When he became a pilot in Syria’s air force, standing in front of my mother in his green military uniform, I thought no one could be braver or stronger than him. But Syria in the 1960s and ’70s was a dangerous place, a place that was changing month by month, and navigating its treacherous waters often proved fatal, even to the strongest. Even as my brother Jaber Abbas Mohamad rose from being a young Baathist officer to press secretary to Syria’s onetime strongman and de facto ruler Gen. Salah Jadid, there were constant dangers. Eventually, they overcame both him and Jadid, although history records the story of only one of them. This is the story of the other.

The Syrian military coup of Feb. 23, 1966, brought to power the most left-leaning faction of the Baath Party. Gen. Salah Jadid, the leader of this group, became Syria’s de facto ruler, but not for long. He entrusted his longtime comrade Gen. Hafez al-Assad with the Ministry of Defense. A principled and ideologically motivated politician with a vision, Jadid henceforward dedicated his time and energy to rebuilding the party along more progressive, radical lines. In the process, he made a fatal mistake by keeping a dangerous distance from the army, delegating its day-to-day affairs to Assad. Jadid appears to have underestimated Assad’s personal ambition and capacity for treachery.

Assad gradually removed Jadid’s men from key military positions, replacing them with his own. By the fall of 1968, he felt powerful enough to threaten a coup against the party leadership, including Jadid. The threat was made during the September 1968 Fourth Regional Conference of the Baath Party. I chose to start this seemingly personal yet essentially political story from that date.

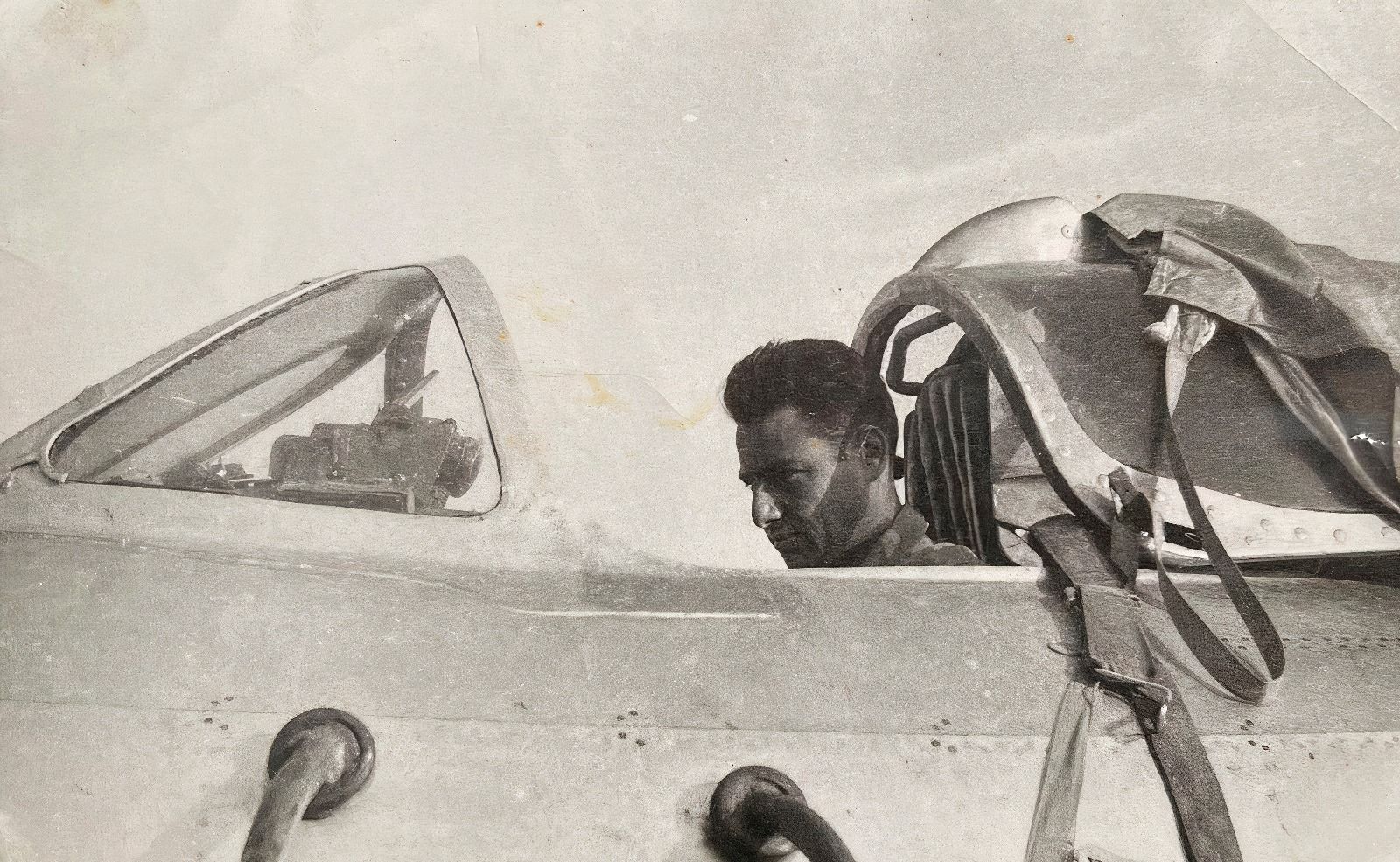

I was 15 in early August 1968, when I moved from Jableh to stay with my brother Jaber for the school year 1968-69. A second lieutenant and a fighter pilot in the air force, he could afford to rent a small but decent apartment in a four-story building in Al-Zablatani Quarter, a predominantly working-class suburb at the eastern edge of metropolitan Damascus.

He was up by 5 a.m. every day, and he had to board a military bus that took him and his colleagues to Al-Dumayr Military Airport, some 30 miles east of the city. One day in the third week of September, he woke me up as usual before leaving, with a surprising request: “On your way back from school, buy more bread and food to last for a few days. A coup is likely to take place, and a curfew may be imposed.” Although I came from a highly political family, I had not yet been involved in political discussions. I could not fully understand why another coup was about to happen.

On the way back from Yusuf al-Azmeh Secondary School, late in the afternoon, I did the shopping. But when I reached the entrance of the building and looked at the window shutters, as I did every day, they were still closed. Jaber had not returned home. I did not know that I was going to wait until the first week of January 1969 before seeing him again.

After a few days, I started to panic. I contacted older relatives who also lived in Damascus. They, in turn, got in touch with close friends of Jaber’s who happened to serve at the same air base. They told us the story. The last day that Jaber left home to go to the air base, he and his fellow pilots were summoned to a general meeting. They were addressed by the air base commander, Col. Naji Jamil, a known ally of Assad. He said that the party had come under the control of “extremists” and Marxist elements that sought to limit the role of the armed forces. He added that they were “conspiring” against the defense minister and his associates. “To stop this conspiracy and to protect the revolution,” he added, “the armed forces would go to any length, including the use of military force.” Finally, he told the shocked pilots that, if necessary, he might have to send some of them to bombard the headquarters of the party leadership in Damascus. “Any objection?” he asked in a threatening tone. Only one brave officer dared to reply. “We cannot bombard the headquarters of our party leadership,” Jaber said. Indignant, Jamil screamed, “Of course we can; we would level it to the ground,” concluding his statement with a series of obscenities.

Jaber was arrested and taken to the infamous underground prison of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate in the heart of Damascus. For nearly four months, he was isolated from the world, humiliated and often tortured. When he was released in the first week of January, he looked pale, thin and frail, but unbroken. After his release from jail, I saw him only once more in his elegant military uniform, in the second week of January. When he returned, he told me he was formally informed upon arrival at the air base that a decision to expel him from the army was made by the Ministry of Defense the day before. It was a devastating blow to an aspiring young officer, in a country where military officers enjoyed a prestigious status.

Fearing prolonged unemployment and financial hardship, Jaber abandoned his rented apartment and moved to al-Rabweh, the westernmost area at the other end of Damascus. There, he sublet a room in an old adobe house rented by an older cousin, a warrant officer in the army. We shared the kitchen and the washroom with my cousin, his wife and three boys. The window of our room was hardly 10 feet from the railroad that connected Damascus to the green countryside of Western Ghouta. Every time the decades-old train passed, the whole house shook and we felt like it was about to collapse.

Luckily, Jaber’s unsustainable situation did not last long. Some older, highly placed Baathists who knew him brought his ordeal to the attention of Jadid, the assistant secretary general of the party, a position above that of Assad according to the political hierarchy in place since the 1966 coup. By then, however, Jadid’s grip on the army had been considerably eroded by Assad’s ongoing campaign to move Jadid’s loyalists to marginal positions.

Jadid sent for Jaber and had a long conversation with him about the incident at Al-Dumayr air base and his subsequent experience in jail. Seemingly unsurprised to hear about Jamil’s threat, Jadid did not comment. But, in retrospect, one can see that he was waiting for the next party conference to have all of Assad’s faction, including Jamil, removed. Jadid was impressed with the young man’s intelligence, education and enthusiasm. He appointed Jaber as his press secretary. Among other things, he was required to scan many Arabic political newspapers and periodicals published in major Arab countries and select important pieces on Syria and the Arab world for his boss to read. He was also tasked with providing Jadid with the latest books — Arabic and translated — about American and Western policies in the Arab world. Once I asked my brother, “Does General Jadid have the time to read?” Jaber told me that his boss started his day by going through important articles about Syria and the Arab world. As for books, he made time for them by dedicating two to three hours every night at the expense of his sleep.

He would use relevant information and data from his readings in political meetings and in the lectures he gave to party members enrolled in educational courses to train as political cadres. He and his qualified associates focused in their lectures on the contemporary political history of Syria and the Arab world and on Western strategies and schemes for the region. Upon graduation, these cadres would go back to their cities, towns and villages to raise the political consciousness of younger and less educated Baathists. After attending a lecture given by Jadid, an excited friend of Jaber’s said to him loudly, “Comrade Jadid is the Arab version of Lenin.”

With a decent salary (though certainly less than the relatively privileged pay he formerly received as a fighter pilot), Jaber could now afford to rent a small apartment in a mainly lower-middle-class area, 2 miles from the daily “horror” of the al-Rabweh-traversing train. It was a tragic irony that the new residence was located on Shari al-Sijn (Prison Street). The street was immediately below one of the Mezzeh hills, on top of which the notorious Mezzeh Prison was visible. During French colonial rule (1920-1946), nationalist fighters were jailed there. But since the era of Syrian military coups that started in 1949, many high-ranking officers and leading politicians, including at least three presidents, have been thrown in this prison for varying periods of time. Twenty months later, in November 1970, Jadid himself was to be imprisoned there by Assad.

Jaber came to know firsthand what kind of man his boss was. He accompanied Jadid to important meetings, mainly to take minutes but also to refresh his memory occasionally regarding certain media reports and pertinent details. Jaber told me that Jadid was a good listener. Getting through the agenda was a team effort, but Jadid’s input was usually significant. As assistant secretary general, he often made the opening statement. Then he listened to each and every participant attentively and was the last to speak. In the end, however, he almost always dominated the discussion, thanks to his informed, intelligent and persuasive arguments, added to his strong personality, charisma and seriousness of purpose. Such qualities earned him great respect.

I myself saw Jadid only once. In the third week of February 1969, amid a family emergency, I had to call on my brother at work. I introduced myself to the man who was supervising the entrance to the small building from a gatehouse and showed him my ID. Suddenly, he asked me to step aside quickly and keep a distance from the entrance. I did as I was told. Then I saw a modest car that stopped in front of the building. I recognized the man who stepped out. Jadid was dressed in a plain khaki uniform, of the sort worn by party and state officials as well as rank-and-file members. The uniform was a symbol of austerity, encouraged by the party leadership. Jadid walked slowly toward the building without looking at anyone, not even the sole military guard at the door, who snapped to attention and gave a loud salute. The driver who moved the car seemed to be the only bodyguard accompanying Jadid. From such a short distance, I could see that he was deep in thought, as though he shouldered all the troubles of the world.

Although he took pride in his new job, Jaber had to get used to the stress of working under a demanding boss. Another source of stress was learning — and living with — highly secret and even frightening information. Sometimes he confided in me, warning me to keep the things I heard from him to myself. One day, toward the end of February 1969, he returned home looking extremely worried. He told me he had accompanied Jadid to an emergency meeting that included Col. Abdul Karim al-Jundi, a close and loyal associate of Jadid. The man was in charge of the once-powerful National Security Bureau. To the party leadership, including Jadid, he was their eyes and ears. In the meeting, they discussed leaked information from the Ministry of Defense about a plan by Assad to arrest or assassinate al-Jundi. The latter said, “I’d rather commit suicide than fall into the hands of a treacherous coward like Hafez.”

My brother told me that al-Jundi and some others among Jadid’s loyalists had long been urging the latter to get rid of Assad and his military faction in a preemptive coup. Jadid rejected the idea. His counterargument stressed party discipline. He repeatedly said that removing Assad and his henchmen was the responsibility of those at the top of the party. Jaber also told me that back in the fall of 1967, in a watershed meeting of the party leadership, Jadid’s proposed motion to remove Assad lost in a 13 to 12 vote. Those who voted against the motion were worried that a conflict with Assad could cause instability in a country that had just suffered a devastating defeat in the June 1967 war with Israel.

When I wondered about Jadid’s stance and his refusal to beat his rival to a coup, my brother explained that Jadid, who already took part in two military coups (on March 8, 1963, and again on Feb. 23, 1966), became averse to these actions over time. He argued that military coups had weakened the role of the party, and that such a recourse ought to be avoided. I asked Jaber what he thought. My brother said he shared the opinion of the majority of Jadid’s military allies, who regarded his stance as idealistic, unrealistic and possibly self-destructive. According to their reasoning, in most Third World countries, the army was the strongest political player. As such, they thought the armed forces should always be in trusted hands, the means notwithstanding. Jaber added that, in private, Jadid’s supporters called Assad “Syria’s Suharto,” in reference to the Indonesian general who only two years earlier had overthrown President Sukarno’s leftist regime in a bloody coup. Jaber was afraid that if Assad carried out his own plans to take power, the progressive policies of Jadid’s faction would be reversed, and the party, along with Syria, would be ruined.

A few days later, on March 2, 1969, al-Jundi shot himself in the head shortly after Assad’s troops stormed his office. Even to leading party insiders, who spoke out many years later, it was a double disappointment that Jadid had not taken Assad’s threat seriously and provided al-Jundi with adequate military protection. On the other hand, Jadid was still adamant that he would not resort to military force to deal with Assad and his men.

Strangely enough, Assad’s feared coup did not follow immediately now that his second most feared enemy, after Jadid, was out of the way. Assad was certainly treacherous and power-hungry, but neither foolish nor impetuous. When the right opportunity seemed to be at hand, he still preferred to bide his time, hoping for optimal circumstances. These materialized in the fall of 1970.

In mid-September 1970, war broke out in Jordan between fighters in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Jordanian army. Strategically allied with the PLO, the Baath Party leadership issued orders to a reluctant Assad to send an armored division to save the Palestinian guerrillas from possible annihilation at the hands of the Jordanian regime. Assad, however, sabotaged the operation by refusing to send fighter jets to provide cover to the Syrian force that crossed into Jordan, leaving it to suffer defeat. Furthermore, the sudden death on Sept. 28 of Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser, a strong ally of the Syrian regime, left Jadid’s faction even more weakened, as the Gulf regimes secretly backed Assad and encouraged him to get rid of the “radicals.”

Jadid made a desperate move against Assad by convening the Extraordinary Tenth Nationalist Conference of the Baath Party on Oct. 30. A resolution — passed almost unanimously — to remove Assad and his main ally Gen. Mustafa Tlass, the army chief of staff, lacked the means to be enforced, since Jadid’s loyalists in the army had already been removed by Assad from their commanding positions. Assad staged his coup on Nov. 13 without a shot being fired. He threw most of the leading figures of the party in jail, including Jadid.

Deemed too unimportant to be imprisoned again, Jaber escaped arrest, but he became jobless. He was saved from possible starvation by his wife, who had just started her career teaching English. A few months later, his friends landed him an entry-level clerical job at the Ministry of Industry. He still had enough spare time to enroll at the University of Damascus, and he had received a bachelor’s degree in history by 1974. Three years later, he received a master’s in economic planning and started climbing the bureaucratic ladder to become a mid-level administrator, despite setbacks and obstacles due to being politically blacklisted, as Assad’s secret police came to control all aspects of life in Syria.

One of Jaber’s wife’s students was Jadid’s niece. Through her, Jaber coincidentally connected with her mother, Jadid’s sister Asya, and her father, Mahmud Jadid, an ex-major who had been purged from the army after Assad’s coup. Jadid’s sister, wife and children were later allowed to visit him in prison once a month. Jaber thus got updated through Asya about Jadid’s health and condition in jail. She told him that her brother was strong and defiant, although he had no illusions regarding any prospect of freedom. He knew only too well how resentful and vengeful Assad was. He told his wife and sister that he would never be released from jail so long as Assad was in power.

Following an abortive coup attempted by Jadid’s loyalists, including his brother-in-law and distant cousin, Mahmud, Assad arrested most of those involved. Mahmud managed to flee the country by walking from Mezzeh to the Lebanese border, a distance of 30 miles. He told me about this life-saving adventure 47 years later. By sheer coincidence, I found out in 2017 that he had left Algeria, where he spent decades as a welcomed political refugee, and ended up in Canada, where he lived just 9 miles to the north of Toronto, my city of residence. We have kept in touch ever since. During our infrequent get-togethers our two main subjects of conversation are Syria during and after Jadid’s life and the 2011 Syrian uprising against Assad’s rule.

Tired of the rising cost of living in Damascus, Jaber asked to be transferred to the Latakia branch of the Ministry of Industry in his home province. Sadly, the move proved to be a fatal miscalculation. After arriving there in 1986, he was frequently harassed by the director general, an enthusiastic collaborator with the mukhabarat (the intelligence agencies). The persecution included the blocking of further promotion and the withdrawal of privileges and benefits such as vacations, sick days and financial bonuses. In his last letter to me in September 1993, one month before he passed away, he told me his malicious boss had taken away his car, which belonged to the ministry but was rightfully part of the privileges associated with his bureaucratic rank. Frustrated and very depressed, Jaber died of a sudden heart attack on Oct. 24, two months after attending the funeral of his former boss and role model Jadid. After languishing for 23 years in jail, Jadid had been taken from prison to a military hospital on the pretext of treating his upset stomach. Within Syria, it was widely believed he was secretly given a lethal injection on Aug. 19, although the regime claimed that he died of natural causes. His body was taken to his village of Dweir Baabda, 15 miles from the Mediterranean town of Jableh. He was buried under the watchful eyes of Assad’s security agents, who enforced his orders preventing any speeches or eulogies after the funeral. It was typical of Assad. His hatred and vengeance knew no boundaries.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.