After extensive negotiations and assurances, my brother finally agreed to lend us his prized 50-inch TV. The family gathered around, equipped with chips and snacks, dimming the lights and transforming our Tripoli living room into an impromptu cinema. It was the first time they would view my debut feature film, “Donga,” a documentary that tells the story of a young man who looks back over 10 years of documenting Libya’s complicated recent history, from the revolution in 2011 through the civil war that tore our country apart.

A cloud of uneasiness settled in the room as we began watching the film. For many of the Libyans I’ve screened the film for, it isn’t an easy watch; it reflects a reality we all lived through a decade ago. The film follows Donga, 19 years old and baby-faced when he starts filming the protests with his friend Ali in the early days of Libya’s Arab Spring uprising in his hometown. Soon, the protests devolved into a war, and the two boys found themselves documenting the front line, capturing the unfolding events. As the intensity of the on-screen war increased, my family peppered me with nervous questions. Who are the people on camera? Where are they now, and when did this happen? I urged my family to focus on the film.

In one scene, Ali, who is also a dear family friend known for his humor, found himself dangerously close to an anti-aircraft firing range. A fighter instinctively thrust him away from imminent danger, but an instant later the fighter’s head was split in two. The photograph of the dead man lying on the ground, his head covered, is accompanied only by silence, a silence that is much heavier sitting in the living room at home than it was in a theater two weeks later at a festival.

The heaviness in the room was not just about the horror on screen, but a confused disconnection between what my family expected a movie about Libya to be — grand, heroic, feel-good and digestible — and the reality of such a close-to-home subject. That is because for generations, two epic, Gadhafi-era films have set the tone for, and in some ways been the sum of, Libyan cinema.

Each year in Libya, after the bustling celebrations of Eid al-Adha and the demanding rituals of slaughtering and barbecuing sheep from early dawn, a serene tranquility settles over the land. As the streets empty, the nation succumbs to a collective food coma.

After this post-barbecue slumber, Libyan living rooms undergo a unique transformation. With tea brewing and the cities slowly waking up, the familiar sound of the score by Maurice Jarr, inspired by the call for prayer in the maqam Hijaz melodic mode, signals the start of Moustapha Akkad’s epic film, “The Message.” It used to air on Al-Jamahiriya state TV during Moammar Gadhafi’s rule. Every year, every Eid al-Adha, every Libyan would watch “The Message,” which premiered in 1976, for the nth time.

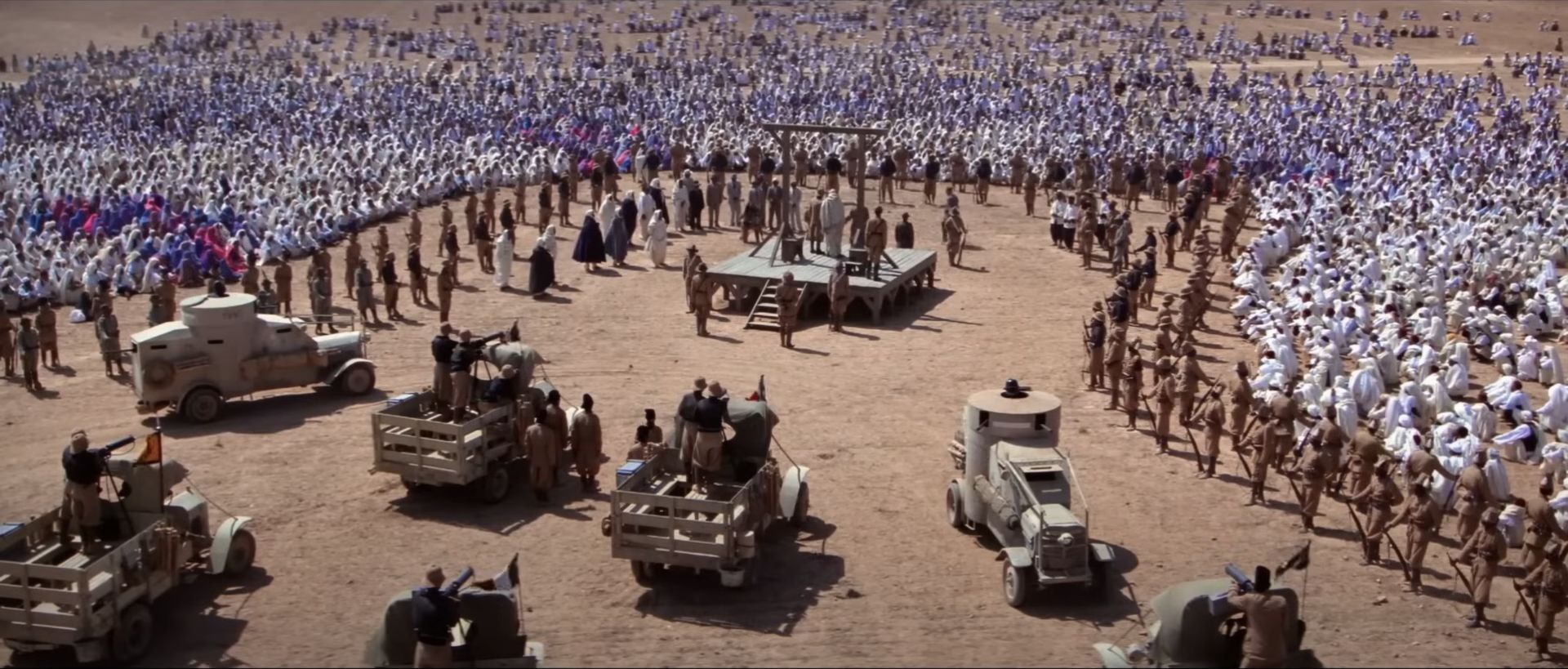

The three-hour film chronicles the life and times of the Prophet Muhammad, and was a monumental undertaking for Akkad. The scale of the production was massive, including a $700,000 replica of Mecca built in Marrakech and shots with 5,000 extras in the crowd. There were sweeping scenes shot in the desert, which gave the film an enigmatic and spiritual quality. Akkad shot two versions of the film at once — one in Arabic, the other in English — with a combined budget of $27 million, a staggering sum that, when adjusted for inflation, would equal nearly $146 million today.

The overwhelming scale of the production wasn’t the film’s only challenge. Because it depicted such a deeply religious subject, Akkad needed to secure approval for the script from a religious authority. (Religious interpretations prohibit physical depictions of Muhammad and his closest companions, so Akkad employed a unique device to captivate the audience by showing interactions with Muhammad through shots from his point of view.) He managed to get the signoff from a scholar at the University of Al-Azhar in Egypt, but the script was rejected by the Muslim World League in Mecca. After more than 13 weeks of filming in Morocco, the giant production was forced to halt by the Moroccan police after Saudi Arabia put pressure on the king.

In a true twist of irony, Gadhafi — who, over time, killed Libyan cinema with years of corruption and censorship — saved the production. He not only offered a new location for filming but generously covered the gaps in the budget that appeared when previous backers balked at the Morocco mishap.

In return for such generosity, Gadhafi commissioned Akkad to direct a film about the storied Libyan resistance fighter, Omar al-Mukhtar. Libya’s second cinematic classic, “The Lion of the Desert,” appeared in 1979.

Shot on location in the eastern part of Libya, on top of the spectacular Green Mountain and on flat desert expanses, “The Lion of the Desert” is set during Libya’s struggle against Italian colonization. It follows Mukhtar and his antagonist, Gen. Rodolfo Graziani, nicknamed “The Butcher of Fezzan” for the executions of Libyans he ordered while military governor of Cyrenaica in North Africa. We first meet Mukhtar in an intimate scene where he is teaching children the meaning of the Quran, when the news arrives of a new general appointed to govern the region. The tension grows slowly, and, though they only meet at the end of the film, Mukhtar and Graziani are in constant conflict over control of the territory. When Mukhtar and his forces are outgunned by the Italians’ heavy machinery, he resorts to guerrilla war in the labyrinth of caves on Green Mountain, which Graziani and his troops cannot navigate.

Eventually, through brutal use of chemical weapons and terrorizing the population, the Italians manage to ambush Mukhtar, whose location is betrayed by a close ally. Gadhafi, according to some, did not want to show the betrayal; it is instead only hinted at by a shot of a black raven flying over Mukhtar before the Italians appear suddenly and capture him.

Like “The Message,” “The Lion of the Desert” aired on Al-Jamahiriya state TV annually without fail on Sept. 16, the anniversary of Mukhtar’s execution at the Slouch concentration camp in eastern Libya, in front of a crowd of 20,000 onlookers — locals forced into attending the hanging of their rebel champion by the Italians.

The Gadhafi-commissioned film was shot in both Libya and Italy. The project had a budget of $35 million (over $148 million today) — exceeding the budget of “The Message.” An entire village set was built nearly 500 miles from Benghazi, while another kind of village — for the crew, with trailers, a swimming pool and a tennis court — can be seen in the behind-the-scenes footage of the film. Gadhafi also generously ensured 10,000 extras from the Libyan army were at Akkad’s disposal.

It is difficult to think that this was the same country where now carrying a small camera in public could land you in an interrogation room, or even get you arrested. The paradox of a nation deeply connected to two films while maintaining complete paranoia about filming is staggering to me. Even though these Libyan-backed films are not Libyan in terms of production, directorship and writing, they are the only two films that all Libyans know and identify with.

For decades, Libyans lacked exposure to films and the freedom to create them. Gadhafi’s regime systematically dismantled the cinema industry in its infancy; by the early ’80s, the leadership of many governmental institutes established during the monarchy, including the General Institute for Cinema, underwent significant changes. Members of Gadhafi’s revolutionary committees who had no background or experience in cinema took control. The institute, later transformed into a public company under clueless leadership, faced mounting debt and unpaid salaries. This financial turmoil culminated in the company’s dissolution in 2002, leading to the closure of all cinema halls owned by the company. Today, some stand deserted, some have been repurposed as clothes shops, and some, like those in Benghazi, have been demolished.

Foreign films, especially American ones, were our main exposure to the world of cinema. However, even these were not easy to get hold of because of the U.S. sanctions on Libya in the late ’80s, which blocked import-export trade. I remember my older brothers getting excited every time they could play the VHS tape of “Mad Max 2,” which my father brought back from a trip abroad. For me, the oldest VHS memory was an anime called “New Tetsujin-28” from 1980, dubbed in Arabic as “Thunder: The Giant” and known in English as “The New Adventures of Gigantor.” It followed the adventures of a young detective and his giant iron robot, created by his deceased father. Despite being packaged for kids in the Arab world and details sometimes being diluted, the series tackled complex and sometimes dark themes of loss, war, fate, freedom of choice and the exploration of space, with a hint of geopolitics. At around 5 years old this might have been my earliest memory of a narrative that sparked thoughts and questions, expanding my understanding of the world.

With the introduction of satellite TV, our homes were flooded with content. In addition to Arab dramas and classic Egyptian films, we were introduced to a steady stream of American films with Arabic subtitles through the newly established MBC channel, which later became a dominant force in Arab satellite TV. Almost every evening around dinner time, we would watch an American blockbuster film — lots of Stallone, Schwarzenegger and Jackie Chan, with the occasional drama or rom-com.

The films that were aired were entertaining, sometimes moving and comfortably distant. Over the decades of exclusively consuming foreign films and the rise of pirated content on the internet, we got used to seeing filmmaking more as an activity done by foreigners than an art form emerging authentically from our society.

Yet in the background of all of this, “The Message” and “The Lion of the Desert” still loomed. Their impact on Libyans was profound and, at times, even absurd. My earliest memory of “The Lion of the Desert” was watching it with my grandmother, the daughter of El Fadeel Bu Omar, Mukhtar’s closest comrade and second-in-command, portrayed by British actor Robert Brown. She would play along with my childhood belief that all films were documentaries portraying real-life events. We waited eagerly for her father to appear on screen, hoping to catch a glimpse of her as well. In a scene where the resistance fighters arrive at the camp where Bedouins were displaced, I would spot him and shout, “Where are you now?!” She would reply, “I must be one of the children in the tents!”

It seems that I was not the only one confusing films with reality. For decades, the actor Ali Ahmed Salim, who played the revered Bilal ibn Rabah — the first person in Islam to make the call to prayer — in “The Message,” would be invited to events all over the country, from university lectures to mosque inaugurations. Often at these events, he was asked to give the call to prayer. People would cry from the spiritual experience of witnessing the actor as if he were the live, embodied reincarnation of Bilal.

The antagonists in these films were not so lucky. Salim Gedarah, an electrician without acting experience working in Akkad’s hotel, was cast in “The Message” as the man who would kill Muhammad’s uncle. His elderly mother in Tripoli, convinced of her son’s wickedness for having played a role in the film, banished him from their home. Only after the intervention of local sheikhs was Gedarah’s mother convinced of his innocence, and she allowed him to move back in.

“The Lion of the Desert” and “The Message” drew inspiration from David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia” — the cinematography of the desert, the jump cuts in the editing; Akkad even hired Anthony Quinn to play leading roles in the English language versions of both films — but unlike “Lawrence,” Akkad’s films centered, developed and fleshed out Arab characters.

The contrasts between Quinn’s characters are striking: In “Lawrence,” he plays Auda Abu Tayi, a brutal clown of a tribal leader, perpetually in search of gold, flat and unconvincing. He is not alone; all the other Arab characters are similarly one-dimensional — background noise for Lawrence’s internal struggles.

But in “The Lion of the Desert,” the roles are reversed: We watch Quinn, playing Mukhtar, struggle through the consequences of his choice to rebel against the machine of Fascist Italy as hundreds of thousands of people are rounded up in concentration camps and villages are burnt. The fascists in the film receive the same treatment that Lean gave Arabs — lacking depth, somewhat foolish, bordering on comical. This narrative reversal is immensely satisfying for the Arab audience, and, because of the general scarcity of developed Arab characters with agency in films, it still stands out.

The beauty of cinema lies in its ability to transcend time and transform perceptions. Despite Gadhafi’s initial attempt to mold “The Lion of the Desert” into propaganda by portraying the Sanusi family, which later led the country to its independence and was overthrown by Gadhafi, as traitors and collaborators with the Italians, the film took on a life of its own, metamorphosing into a powerful symbol of resistance for Libyans, most ironically against Gadhafi’s own tyranny. The eruption of the anti-regime protests on Feb. 17, 2011, witnessed Mukhtar’s image once again emerging as a symbol of defiance. His portrait could be seen on flags and posters of the anti-Gadhafi forces during the uprising that followed; there was even a brigade under the name of Omar al-Mukhtar fighting against Gadhafi.

In the scene depicting my great-grandfather Fadeel’s death in “The Lion of the Desert,” Italian forces use the chemical weapon known as mustard as part of an ambush to push the Libyan fighters up the mountain. Amid the chaos, Fadeel is shot in battle. As Mukhtar rushes to him, he quickly realizes that Fadeel is dead. Omar covers him, and with no time for mourning, he escapes the mustard, moving up the mountain, as my great-grandfather’s body is romantically consumed by the mustard mist.

In reality, my great-grandfather met a more gruesome fate. Following his death, a Libyan soldier whom the Italians had turned decapitated him, and his severed head was prominently displayed in Benghazi’s main square, hanging for days as a brutal reminder of the resistance’s fate.

The cost of joining the resistance was high, and many opted for survival, even if it meant living under Italian rule. Life under occupation was more complicated than the simple binary of heroes and traitors in the film; there were also survivors, people who just wanted to survive and could not or would not resist and face the Italians. Those people were forced to make choices based on their personal experiences. The complexities of these choices are what captivate me.

As a storyteller, I try to understand human contradictions with all their complications and attempt to portray these in a way that resonates with the audience’s lived experiences and values. This is a laborious process, especially when it comes to portraying a reality that is more absurd than fiction itself.

Since 2011, the reality for our generation in the Arab world has been an unending rollercoaster. Filmmakers from Libya, as well as those from across the broader Middle East and North Africa, find themselves navigating the balance between the stories they want to tell, the stories they need to tell and the stories they experience firsthand.

On an international scale, despite the exceedingly complex reality of the region, there is a widespread expectation among film festivals and producers that filmmakers should guide audiences morally and establish a clear judgment on who is good and who is bad in a film. For me, that feels like a dangerous path to take creatively; the moment I start to pass judgments on characters in a film, they become void of depth.

In my 2019 short film, “Prisoner and Jailer,” structured around a role reversal of two characters in the immediate post-Gadhafi period, a man previously imprisoned by a Gadhafi loyalist becomes his jailer after the 2011 revolution. The two characters in the film are ideologically driven — one by an extremist version of Islam and the other by Gadhafi’s indoctrination. While the film attempts to empathize with both men by highlighting their similarities and shared experiences, it intentionally refrains from offering a final verdict on who is right or wrong. This ambiguity and lack of didactic “moral clarity” unsettled many Libyan and some other Arab audiences and led to a wide range of reactions to the film. In Tunisia, the film has been labeled sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood, while in Egypt it was perceived as against them.

But there are positive developments. With the rise of streaming services reaching Libyan audiences, exposure to diverse characters and thematic representations in films and series has become the norm, especially for younger viewers. Morally complex characters and challenging points of view resonate well with today’s Libyan youth. This exposure may shape their preference for complex Libyan characters.

And yet, challenges remain. Libyan reactions to films coming from Libya since 2011 often echo disparaging sentiments such as “We don’t need films, we are living an action movie every day!” Artistic expression is viewed as a form of luxury for the good times. A lot of expectations from the audience also remain — that films should satisfy Libyans’ need for self-validation while attempting to familiarize an international audience with the intricacies of our nation.

After the success of “Lion of the Desert,” Gadhafi’s regime bankrolled films with similar themes, but they all flopped. Gadhafi decided that his two successful films were the sole cinematic representations the nation needed, encapsulating core elements of the identity that he wanted. No other Libyan films to date have fared much better, either inside or outside the country. Although Libyan films have been showcased in regional festivals since then, suppression of artistic expression and the corruption of Libya’s cinema institute led to severe decline. The state has gradually eroded what was left of the cinematic culture of the country, leaving only two emotionally, religiously and nationally charged productions with which Libyans can identify.

Since “The Message” and “The Lion of the Desert” were first viewed by Libyan eyes over 30 years ago, these two films have dominated our screens on major holidays and have become an intricate part of our lives and routines. The repeated viewings and the intimate relationship Libyans share with these films have created an almost hypnotic, soothing effect. Similarly to watching Christmas films in the West, the predictability and sentimentality of the movie during a time of family gathering impart emotional value, stability and rootedness.

The vision of Libya in “The Lion of the Desert,” despite its grim reality, is the one with which we are most comfortable. We see ourselves as united, noble and conservative Muslims, often referring to our nation as “the country of a million memorizers of the Quran.” It’s a vision that helps us reconcile with the ugly reality of a fragmented, war-torn country drowning in corruption and conflicts over resources — essentially, everything the Libyans of “The Lion of the Desert” are not.

Back home in Tripoli, as my film drew to a close, my family looked tired after reliving the last 10 years of our history through Donga’s eyes. Credits rolled, and we sat in silence for a moment. My brother eagerly took his TV back to his room and turned on the harsh light. The cinema returned to a living room again, satellite TV was plugged in, everyone scattered around the house preparing to sleep and my family would not likely watch another long Libyan film for a while.

It seems like there are so many factors that need to align for Libyan cinema to be revived again: economic and political will, investment, infrastructure and a lot of capacity-building. But most importantly, we need to reframe our understanding of filmmaking. Cinema is not a luxury for the good times; it is more than a mirror of society. It’s a way to communicate with ourselves and with the outside world. If we do not allow ourselves to say what we want, we will continue to be consumers of other voices and continue to hold a double vision of ourselves — the one that we like to see in “The Lion of the Desert” and “The Message” and the one we live with.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.