Listen to this story

I first read James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” when I was 14 and already understood that writing was what I had to do in order to live. Stephen Dedalus’ artistic ambition, his adolescent passion and, especially, his intransigence, his defiant “non serviam” (“I will not serve”) resonated, as did his scathing take on Ireland. Underlined in my old Penguin paperback is the following: “Ireland is the old sow that eats her farrow.” The “cold violence” in Stephen’s voice as he utters these words to his friends was a tone I recognized. Leaving aside the sexism of his metaphor — which, to be frank, I wouldn’t have noticed then — 14-year-old me cheered from the sidelines, discerning in his Ireland my Kuwait. A few lines earlier, Stephen has this to say: “When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.” Whether Stephen escapes is not for me to tackle here. However, 38 years on, as I teach “Portrait” to my students at Kuwait University, I feel compelled to consider where I stand today in relation to Stephen’s youthful judgment of Ireland and, by extension, my own of Kuwait, and to what degree Joyce’s literary experiments have shaped mine.

My copy of “Portrait” was, in fact, my older sister’s. At the time, she was an undergraduate at Kuwait University. She didn’t need it anymore, so I nabbed it. That year I was deep into the first volume of “The Diary of Anais Nin.” I had been keeping a diary since the age of 9, so Nin’s writing resonated. She captured the obsessive quality of diary writing, and, even more significantly, she conveyed a sense of writing as a vocation: “Writers do not live one life, they live two. There is the living and then there is the writing. There is the second tasting, the delayed reaction.” Her words came as a revelation, confirming that the hours I had spent reliving days and years in writing, recording and, crucially, reshaping events and dialogue, were part of the practice of becoming a writer. That largely unseen — unread, as it were — chunk of my life felt validated as never before.

When I was coming of age in Kuwait in the ’80s, there were no signposts for how to become a writer, especially not for someone whose first language was English. Even for those who wrote in Arabic, fiction writing was something to be done on the side. Writers were full-time journalists, worked at some government job or private business; they wrote fiction part time. Creative writing programs were unheard of. Already distanced from the cultural and linguistic milieu because I went to an American school rather than the government schools most Kuwaiti girls attended, and knowing that I wanted to be a writer in a place inhospitable to them, I felt at best estranged, at worst desperate. Nin’s determination and the value she attributed to the process of writing gave me the courage to keep at it.

In “Portrait,” Joyce intensified for me this sense of writing as a legitimate calling. It’s in the title, after all. As a Kunstlerroman, or artist’s novel, “Portrait” traces the path of Stephen coming into his own as a young artist in the making. Stephen reads and is obsessed with words; he debates aesthetic theories with the full arrogance of youth; he writes a competent villanelle; he extricates himself from at least some of the clinging nets; and we leave him on the brink of venturing into the world, certain of his destiny. Stephen’s nets were my own, and I saw in his success a way out. He was Icarus before the fall, about to fly toward the sun, full of promise and potential glory. I was drawn to Icarus then, the boy’s wild folly and pride, and felt particularly connected to him by way of the Kuwaiti island of Failaka, named Icarus by the ancient Greeks who inhabited it in the fourth century BCE. I learned about this fascinating history of Failaka around the same time I was reading Joyce, which struck me as a telling coincidence.

Nin’s writing opened another door for me, similar to the one Joyce would lead me through. “I have rejected,” Nin declared, “all conventions, the opinion of the world, all its laws. I am not obliged … to play a social role.” What Stephen condemns as the “hollow-sounding voices” of church, nation and family, Nin rejects in other words. Against these conservative conventions, both Nin and Joyce describe the sexual awakening of adolescence — Nin, at 28, later than we might expect, not surprising given her particular context; and Stephen, in his teens, right on target. I, too, was on target, but, as with the notion of becoming a writer, becoming a sexual being — a sexual girl, no less — was not easily articulated or navigated in the Kuwait of that time. It may have been easier for me than for other Kuwaiti girls because of the school I attended and because my parents were more lenient than others, but I still felt restricted by the nets of propriety. The repercussions could be serious: A girl risking her or her family’s reputation would threaten her prospect of marriage, the primary goal at that time (and, for the conservative majority, still today). Fiction became the place where my wayward desires, like my writerly aspirations, were not only sanctioned but celebrated.

Writing and sexual desire dovetailed for the first time, subversive and pleasurable in equal measure. Stephen, in a moment of epiphany, abandoning, finally, the call to priesthood and its attendant burden of guilt, expresses the promise of youth this way:

He was alone. He was unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life. He was alone and young and wilful and wildhearted, alone amid a waste of wild air and brackish waters and the seaharvest of shells and tangle and veiled grey sunlight and gayclad lightclad figures of children and girls and voices childish and girlish in the air.

This breathless tumble of repetitive, incantatory language conveys the urgency experienced in the body: for writing and as desire. Heady stuff for a 14-year-old growing up in a Muslim-majority country. I absorbed it earnestly, feeling duly vindicated.

The irony of “Portrait” was completely lost on me the first time I read it. Only later, in my 20s, did I notice Joyce gently poking fun at the grandiose, hopelessly Byronic Stephen. With the passage of time, Icarus’ folly began to register from the perspective of his father Daedalus’ sagacity. Some of this begins to surface toward the end of the novel, with the abrupt shift from third-person free indirect speech to the first person, in the form of Stephen’s short diary entries in the days leading up to his ostensible departure. The final line is a prayer of sorts: “Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.” A prayer not to God but to creativity itself, to skill and invention, as symbolized by the father. This would seem to contradict the persistent drive away from family that had propelled the narrative forward up to this point. Is Stephen more entangled in the nets than he believes? In his penultimate diary entry, he declares: “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” If that’s what he feels, then he is indeed caught, repeating experience for the millionth time, following paths worn down by preceding generations, bound to his race with an oppressive inevitability. Joyce’s knowing, equivocal snipes at Stephen deflate his youthful buoyancy for the reader. At the same time, they announce the triumphant arrival of the artist, creator of Stephen.

Joyce successfully forges the “uncreated conscience” of his race in his writing. He fabulates a Joycean Ireland for all time, preparing the conditions for a future that did not exist before he invented it. He escapes the nets by naming them, then reshaping them in language. His expression will not evoke everyone’s Ireland, but it continues to resonate with many. His is an Ireland of not belonging, as opposed to an already created conscience or inherited identity. The conscience Joyce produces remains uncreated, always in process, always open to transformation. Joyce, unlike Stephen, is not repeating an exhausted formula for being Irish or for being an artist. He leaves these questions as open as he leaves the ending of “Portrait.” In doing so, he depersonalizes the stories of nation, race and belonging, emphasizing instead the endless potential of what these elements can become across time and space.

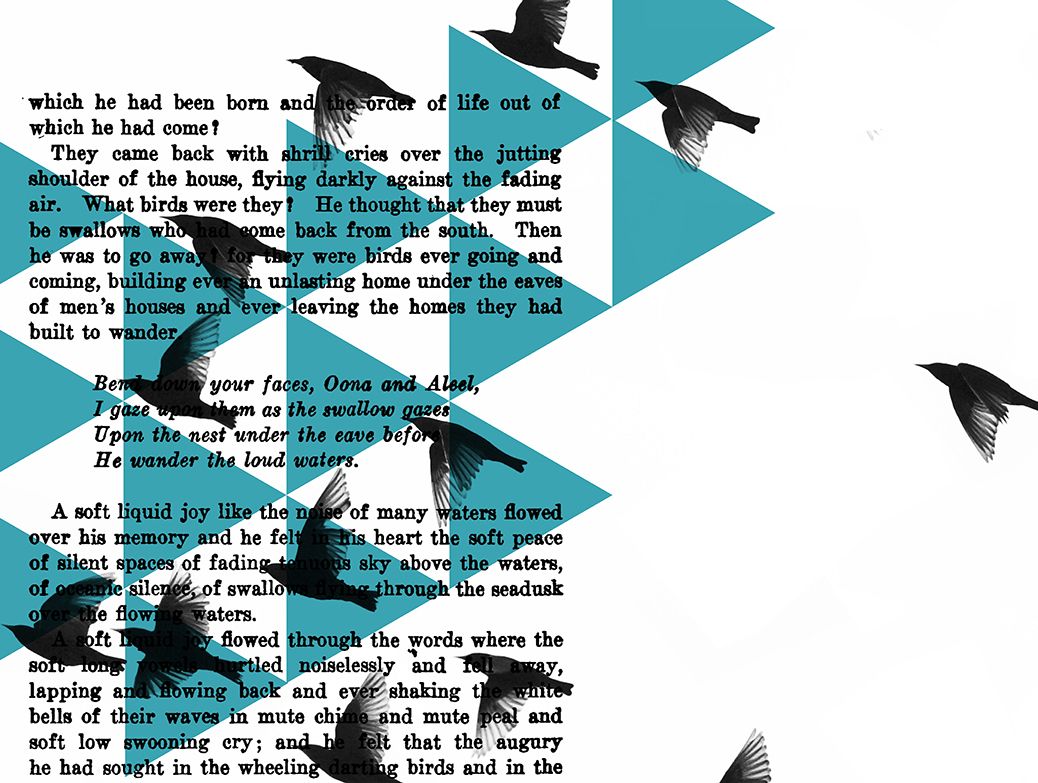

Joyce’s Ireland has traveled far beyond any strict national borders, all the way to Kuwait. The title of my debut novel, “An Unlasting Home,” comes from a quote that appears toward the end of “Portrait,” which embodies this sense of not belonging:

Then he was to go away for they were birds ever going and coming, building ever an unlasting home under the eaves of men’s houses and ever leaving the homes they had built to wander.

Birds throng “Portrait,” and it was for this reason that I turned to it for inspiration when my working title stopped working. The trope of birds runs through my novel as well. To build an unlasting home and then leave it behind to wander is what the women characters in my book do, like the strange birds they are. This element becomes the driving force in the narrative. I, too, in my writing, fabulate a Kuwait of the imagination, one that refigures a codified history toward a potential present and future always in the making, especially through language and style. I was not consciously thinking of Joyce as I wrote “An Unlasting Home,” but after its completion I recalled the old artificer, with his eagles, herons, geese, seabirds and swallows, and understood just how much of him has seeped into me and how grateful I am for it.

I’ve been teaching “Portrait” in my modernism classes at Kuwait University off and on for 20 years. In the past decade, there has been less of a demand for classes in modernism, so I haven’t returned to it much. This year — because I insisted, because I missed it — a modernism class was slotted into the schedule and seven senior undergraduates signed up for it. Seven. What can Euro-American modernism mean to an undergraduate student of literature in Kuwait today? How might Joyce’s “Portrait” speak to them? My students, who are likely similar to undergraduates the world over, are much more focused on claiming identity than appreciating the power of not belonging. They are eager to represent themselves with labels that fix their prioritized features, whatever these may be. Their favored points of identification provide comfort in an atomizing world of social media and hyper-consumerism, looping them into a group where they can belong. What this desire to identify forecloses, however, is contingency, openness, transformation — that is, the possibility that things might be differently arranged. Not that my students recognize this. They do not see their desire for identity as an example of hurtling into Joyce’s nets; they see it, rather, as a form of self-expression. That this algorithmic self-expression is so easily exploited seems indiscernible to them.

In a world wracked by migratory and refugee crises precipitated by war, persecution, famine, poverty and occupation, among other calamities, it is not my intention to romanticize the notion of not belonging. All too often migrants and refugees are subjected to tremendous hardship, racism and trauma, and these serious issues should not be understated or ignored. The voluntary exile of an intellectual writer, such as Joyce, is not comparable to the involuntary escape of a person facing imminent annihilation. Yet writers from Joyce and Milan Kundera to Erich Auerbach and Edward W. Said, their lands under occupation, have extolled the value of exile, of not belonging, citing the critical insight it induces. To not belong to one identity, one home, one language, one nationality activates a critical awareness of difference or otherness, what Said calls a “contrapuntal perspective,” what Joyce calls “epiphanies.” This critical insight makes it possible to perceive things from a bird’s-eye view, which affords a wider, more inclusive perspective and is therefore likely to be less judgmental or dogmatic than one firmly fixed in habituated identities.

For modernist artists and critics, including Said’s favored theorist Theodor Adorno, difficulty was the mark of critical thought. Language, form or style that slows down perception enables new perceptions, sensations and conceptions to emerge. Slowness is the opposite of the speeded-up digital culture my students gorge on. For them, reading Joyce was a kind of torture. We tackled the text page by page, going over lines, reading the words aloud. Left to their own devices, they would not have read “Portrait,” relying instead on online summaries. Was it worth it? Could they see the value in the process? I’m not sure. I did not witness any obvious epiphanies in class or in their writing, but who knows? That we did it together is itself a small victory. It allowed me to share the experience of reading, which I took for granted when I was their age. I don’t mean close reading in the New Critical sense but simply reading words arranged provocatively on a page. The leap from experimental writing to nonconventional thinking and, even further, to nonregulated being in the world was addressed. I’m not sure they felt it in the same visceral way I felt it at 14. They are overwhelmed by so many forms of seductive, addictive distractions competing for their attention, they can’t be blamed. Yet in Kuwait, little has changed when it comes to the social restrictions enforced by family, religion, language, nationality and the law. In fact, restrictions have intensified for those in more conservative and traditionalist communities, which now form the majority. So it would seem that the critical skills most beneficial for questioning these restrictions — skills difficult modernist texts might cultivate — are the same ones most undermined by a dominant consumer culture. It’s a conundrum not easily solved.

In my department of English at Kuwait University, students can specialize in either literature or linguistics. Most choose linguistics, citing expediency and ease. This wasn’t always the case, but it is now. In the war between easy and difficult, easy wins every time, which does not bode well for Joyce in Kuwait, nor for modernism and what philosopher Marshall Berman describes as its “critical bite.” We — teachers, writers, intellectuals, ethical beings — may lament the demise of critical thought in the face of digital media and, soon enough, if not already, artificial intelligence. We will be perceived as being out of step with contemporary culture, as elitist or old-fashioned, if not old (“The horror! The horror!”). Still, a certain kind of writer will persevere, flying in the face of convention. There may be an ostrich-like, Stephen-like quality to this intransigence (“non serviam”), and it may be futile. Nonetheless, that futility may contain an untimely little seed, an alternative future unfolding that cannot be predicted or cannibalized in advance. This is not an idealistic expression of hope. It is instead an affirmation of the persistent power of literature as a line of flight toward that untethered, unnamable place I call home.

This article was published in the Summer 2023 issue of New Lines’ print edition.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.