Listen to this story

My partner, Sue, believed she was a Māori princess. It began as an instinct. Sue’s mother, Norma, always carried herself with a serene, self-contained dignity. Communicated in Norma’s restraint was a quality — or essence — known to Māori as “mana.” You don’t have to be of chiefly descent to have mana, but you must have mana to be chiefly.

Norma was quietly proud of her Māori heritage. She spent hours weaving the intricate “tāniko” bodices that the women of her local “kapa haka” (an Indigenous dance group) wore when they performed on stage. She learned “poi” (the swinging of a small ball made of leaves and fibers attached to a string) and the complicated choreography of the dance group. Norma was proud of her people, even in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, when being Māori was regarded as shameful and they were the target of systemic racism. The Māori were excluded from bars and barber shops, segregated at the cinema and seated in the back of buses. In certain towns, and in certain contexts, a kind of apartheid operated in New Zealand (which the Māori call Aotearoa), separating pale-skinned Pākehā (European) New Zealanders from Indigenous Māori. This discrimination did not diminish Norma’s commitment to her culture or her people.

But Norma’s mana was not proof of a noble line. In fact, it was Sue’s pro-golfing cousin, Terry Kendall, newly on the international golf circuit, who provided Sue with her first thread of evidence. Terry, on his trips home, had met with people who told him his family tree could be traced back to the auspiciously all-powerful Chief Pōtatau Te Wherowhero.

Born at the end of the 18th century, Chief Te Wherowhero was crowned King Te Wherowhero in 1858 by a confederation of Waikato tribes, their territory covering 10,000 square miles and stretching from the Bombay Hills and Port Waikato in the north to Mount Ruapehu in the south. This was so Te Wherowhero could represent his people on equal terms with the colonizing British crown. The 1769 arrival in New Zealand of Capt. James Cook had solidified Britain’s expansionist aspirations to colonize the region. Cook circumnavigated the islands creating a relatively accurate map, which alerted Britain to their potential for exploitation of resources and for colonization. Through the 18th century, European sailors, whalers, traders, missionaries and lawless adventurers visited frequently.

The violence and misrule of this period were among the imperatives that drew many Māori chiefs, in 1840, to sign the Treaty of Waitangi. The pact brought New Zealand into the British Empire while promising the Māori equal rights as British subjects. From its inception, the treaty was highly controversial; Te Wherowhero was among the “rangatira” (Māori nobility) who refused to sign it. He doubted the motives of British representatives and wanted more autonomy for his people.

Conflict over interpretations of the treaty and the sudden influx of British settlers were triggers for the New Zealand Land Wars (1843-72). During this time the Māori lost much of their territory and sovereignty. The history of Te Wherowhero’s Waikato confederation is especially grim. Gov. George Grey presented the Indigenous people of the area with an ultimatum: Either pledge allegiance to the queen or leave the land between Auckland and the Waikato. This meant thousands of Māori were forced to flee the region and were made homeless.

It was Te Wherowhero’s hope that he, as a First Nation Māori king from 1858, would match the status of the queen of England, ruler of an ever-expanding global empire. But sadly, the great chief would live only two more years, until 1860, before the Waikato confederation were casting round for another candidate for royal investiture.

The pivotal piece of information Terry uncovered from his early investigations was that long before Te Wherowhero achieved his rise to power, he had taken a first wife known as Hinepau, who had died in childbirth. The surviving child, a daughter, Irihapeti Te Paea, was reputed to be Sue’s great-great-grandmother. So, according to Terry’s inquiries, Sue’s maternal Māori line sprang from a great chief and anointed king, and she was a princess.

This was, however, just a vague notion when I met Sue, some years later. She had noted Terry’s findings, but these jottings had disappeared long ago under a pile of family calamity, beginning with the tragic death of Sue’s father, Vince, in Palmerston North at the hands of a 16-year-old learner driver. Sue’s family, who had already gathered from around the country to celebrate Vince and his wife Norma’s 40th wedding anniversary, attended his funeral instead.

Births and deaths dominated Sue’s existence, until, rubbed raw, the facts of her family history were only dimly traced in her memory.

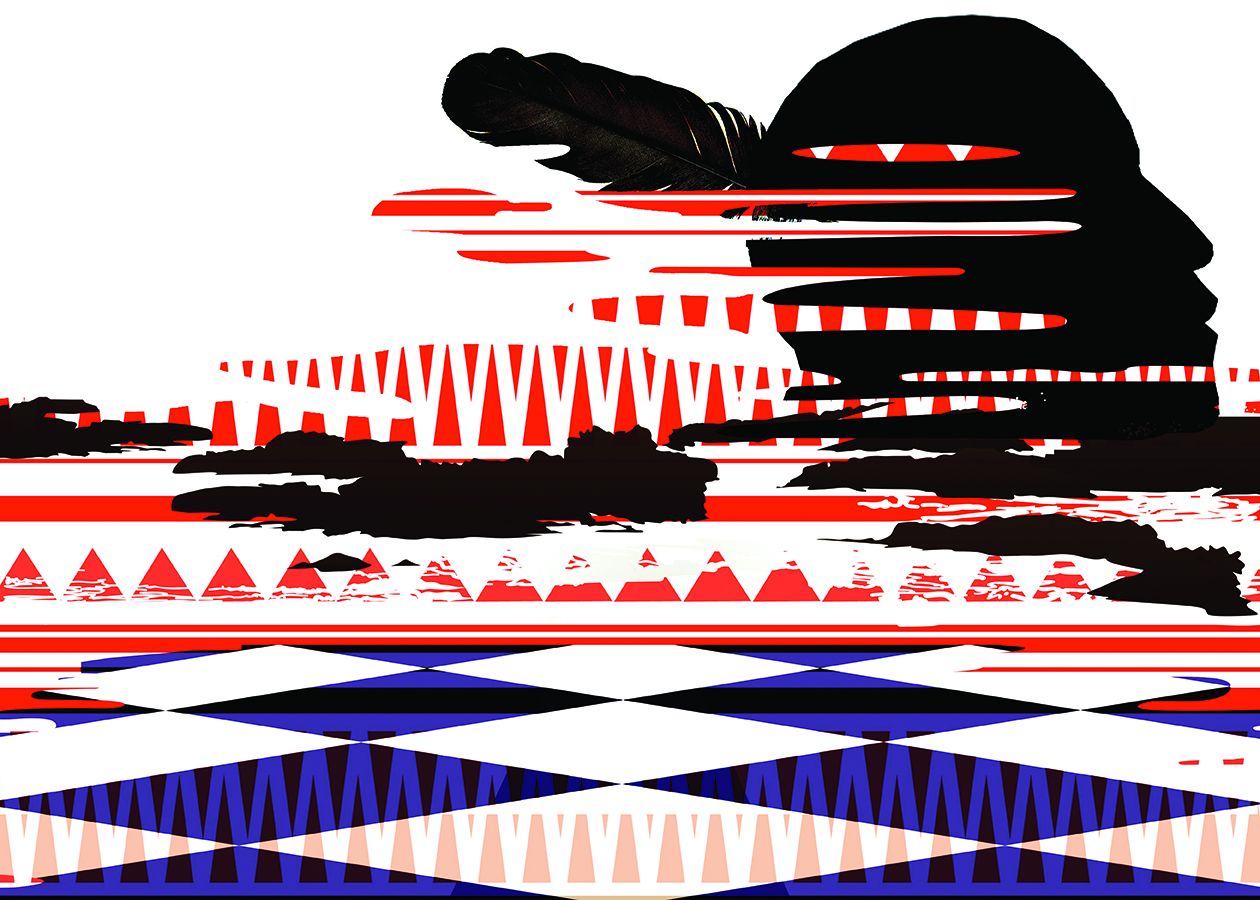

It was a chessboard that inspired Sue’s search. I had worked for four years carving a bone chess set that depicted my Viking lineage. But it was only one side of the board, and I wanted Sue to find out about her family so we could fill out the set. On her side the king would be Te Wherowhero and the queen his first wife, Hinepau — Sue’s great-great-great-grandparents.

“You need to research your family,” I told Sue. “Find out whether your cousin was right.”

Sue’s investigations began with the accidental discovery of Russell Bishop’s essay in a book on the “whakapapa” (genealogy) of Irihapeti Te Paea, in the research library of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

“See, I told you I was a princess!” Sue shouted across the room to the astonishment of the library’s hushed readers. “Irihapeti Te Paea is my great-great-grandmother, and she was the daughter of King Te Wherowhero. I knew it! Everything Terry said was true!” she exclaimed. Sue had scanned through Russell’s introductory essay, then found herself named among the lengthy list of relatives. This was confirmation, a eureka moment marking the beginning of her odyssey.

Sue stacked her photocopied pages and stowed them away carefully in a clear file. Reading the essay properly would have to wait until we were home. Sue would ultimately learn that this book on Irihapeti Te Paea and her whakapapa had been the centerpiece of a family reunion in 1994 at Port Waikato, where Irihapeti and her husband, John Horton Mackay, raised their 12 children.

Having a whakapapa for Māori is more than having a family tree. The names of “tīpuna” (ancestors), the events, the places, the mountains and rivers locate and anchor Māori on the timeline of their heritage. It provides a connection to the physical and spiritual, to history and mythology. It grounds those who are in it within Māori custom and philosophy. It is a “taonga” (treasured possession) and like an artifact is resonant with stories. This is the miracle of whakapapa: when ancestors whisper secrets to their “mokopuna” (grandchildren). This way the shame of one age can become the pride of the next.

Aotearoa is one of the most recently inhabited countries in the world. There is debate about its settlement, but it is widely accepted that the first settlers from East Polynesia arrived between 1250 and1300 CE. The founding peoples arrived in a series of migrations that involved small tribal groups. The navigator Kupe is credited with discovering Aotearoa. He and successive generations of travelers set sail in great seafaring vessels called “waka.” The journey across thousands of miles of sea was treacherous.

Although these giant canoes were rigged with sails and could be maneuvered by paddles, they were open to the elements, and therefore susceptible to sinking in storms. The people of the waka depended on the water and dry stores they could carry, and the fish and bird life they caught along the way. All journeys were perilous, and some expeditions never made landfall.

Sue’s ancestors trace their whakapapa back to this migration. They do this in “waiata” (songs) passed like Viking sagas from generation to generation. There are differing accounts. Below is the one Sue has chosen, which was inspired by the migration story in Marie Nixon’s “Credibility and Validation Through Synthesis of Customary and Contemporary Knowledge,” a 2007 doctoral thesis at Massey University, Wellington. It belongs to the great chief Te Wherowhero’s family and begins around 1250, on a beach in Hawaiki, where a waka was ready to sail.

The great waka, Tainui, has been carved from a single tree. This giant of the forest was fed by sacred soils, planted on the burial site of the chiefly child, Tainui. As it grew tall then towering, rituals were performed. Its journey from tiny seed to colossal tree has been sanctified. During Tainui’s carving, prayers and incantations were chanted. On one side of the enormous waka is an outrigger named Takere-aotea, which offers stability and shelter from the waves. Two other grand canoes, similarly blessed, one called Mātaatua and the other Te Arawa, will join Tainui in its epic quest.

Generations have lived and died in expectation of this day. Waka are sacred vessels. Their histories from earliest days navigate the dangerous waters between humans and the gods. Especially Tāwhirimātea, god of the winds, and Tangaroa, god of the sea. Carvings along the sides and at the prow and stern of these waka are a conversation with the spirit world, placating the gods, and pointing to past tīpuna and to future “iwi” (kinship groups) who will anchor their bloodline to the migration of these canoes.

Travelers, Toi and Kupe, voyagers who crossed the ocean, have told of cooler territories to the south. Great expansive lands they called Aotearoa (New Zealand). Huge islands that sat on the horizon like a white cloud waiting to be discovered.

The celebrated chief, Ngātoroirangi, has been chosen to command the Tainui waka on this perilous expedition. He is an experienced navigator. Ngātoroirangi can read the stars, the sun and the moon. He observes the migratory movements of birds. He understands the winds, the clouds, the currents, the sea and the seaweed it carries. Ngātoroirangi is a lodestar, a guide who knows the rhythms of the universe.

There will be starvation and death on this long, long journey. But, in spite of the suffering and the storms, Ngātoroirangi will find his way across the oceans. The canoe will land near Cape Runaway in the Bay of Plenty. Ultimately Ngātoroirangi and his waka will travel as far north as Whangaparāoa and the Waitemata Harbor, and explore the tributaries of the Waikato and Waipā Rivers. Its passage will end on the east coast at Kāwhia. Two limestone pillars at Maketu Bay mark the end of its voyage, and the beginning of a new life for its people.

In waiata that sing of Ngātoroirangi, who navigated the seas to bring his people safely to land, Sue learned of her great-great-great-grandfather, Te Wherowhero’s, beginning in Aotearoa. For he belonged to Ngāti Mahuta, a tribe whose songs hearken back to the waka of Tainui and Te Arawa.

The waiata of Sue’s great-great-great-grandmother’s people, however, sing of a different journey. Her tribal waiata tell of the first settlers of Aotearoa returning to Hawaiki, to bring back the sweet potato, known to Māori as “kūmara.” Māori lived largely on shellfish, small birds, dogs, rats and fern roots and shoots, boosted intermittently by seal meat and the flesh of the giant flightless moa bird. The cultivation of kūmara in large terraced gardens introduced greater diversity to the hunter-gatherer diet, allowing the support and settlement of larger populations. Kūmara grew better on the North Island, where the weather was warmer. Because of the lack of a diverse agricultural food supply, the arrival and survival of the kūmara was paramount. There are various versions of what happened. The one below is informed by the scholarship of Bradford Haami’s essay “Mātaatua and Ngāti Pūkeko,” published in a family history titled “The Whanau of Irihapeti Te Paea (Hahau): the McKay and Joy (Joyce) Families” (compiled by Rex and Adriene Evans, circa 1994). It was this story that Sue was drawn to.

Near the town of Whakatāne, there is a stretch of pure white sand. In the bay that it fringes, even before the presence of people, was Whakaari, a great ivory-coloured island with a heart of spuming fire. Over centuries, pumice from Whakaari gifted the beach at Whakatāne with its mantle of alabaster sand. On fine days when its god was at peace, the sight of Whakaari from the beach was of a blue-grey cone rising up from the sea: the sky above it a billowing cloud of soft whites and blues.

Whakaari is at peace the day a young woman named Kurawhakaata is standing on the beach looking across at the steaming volcano. But in that moment, she sees something else: an enormous canoe with a triangular-shaped sail heading towards the shore. Kurawhakaata, the daughter of the celebrated chief Tamakihikurangi, is not afraid of these strangers. As the waka gets closer she calls to the voyagers, welcoming and inviting them to feast with her people at their “pā” (village). Only the best food is presented to these honoured guests.

In response, the voyaging chiefs Hoaki and Taukata offer a “koha” (gift) of treasured food they have carried with them. From their girdles they draw dried kūmara, the last of the store prepared for their trip. The people of Whakatāne are overwhelmed. This is a gloriously satisfying food, with a flavour they have never tasted before. Hoaki and Taukata explain that kūmara are the fruit of the soils of Hawaiki.

So intense is the desire to have this food that their chief sails with Hoaki and Taukata to Hawaiki to bring the kūmara back to his people. Eventually, a canoe carrying its valuable cargo returns to Whakatāne, and the kūmara is planted.

It is the mokopuna or progeny of these fearless sea travelers that is Sue’s maternal line. Among their descendants is the fearsome warrior Pūkeko, whose courageous name will be given to her warrior tribe Ngāti Pūkeko of Whakatāne. From this chiefly line came Sue’s great-great-great-grandmother, Hinepau.

Hinepau was born in the opening decade of the 19th century, when muskets were first arriving in Aotearoa. Soon Pākehā guns would wipe out thousands of young warriors in warfare. Māori war canoes carrying armed raiding parties traveled the length and breadth of the country, fighting for territory and exacting “utu” (revenge) for perceived insults, attacks or slayings. This story of Hinepau’s seizure and her first meeting with Te Wherowhero is inspired by the research of Russell Bishop and his essay “The Family of Irihapeti/Te Paea,” also published in the family history of the McKays and Joyces.

Hinepau is a “puhi” (young maiden) of high birth. The white sands where Kurawhakaata welcomed those ancient kūmara-bearing visitors from Hawaiki are her playground, as is the sea that laps its shores where she gathers “kai moana” (seafood). Her life has been patterned by the seasons. Hinepau has seen 12 summers come and go, and is now approaching the zenith of another. She is young, but not a child anymore. Hinepau has an adolescent energy, tempered by the dawning desires of womanhood.

It was on a canoe trip to Whakaari Island to gather muttonbirds or tītī, that the abduction happened. Hinepau escapes the main party to hunt tītī alone. She is usually accompanied by several female attendants, but today there is only one, and when she becomes distracted for a moment, Hinepau is gone. The day passes and she has a hefty haul of birds. Hinepau has her head down, the basket of dead tītī on her back weighing heavily, when she sees them. Her heart races with the surprise. The shock. In front of her stands a man, a warrior not of her “hapū” (tribe), and behind him are more strangers. A war party. Hinepau turns to run back across the jagged, unforgiving rocks.

She knows her flight is futile, and even before she stumbles Hinepau is caught, and carried off to a waiting war canoe beached in the next bay. Her captors see from her dress and demeanor that she is of noble birth. In her hair are the black feathers tipped in white of the “huia” (a sacred bird); on her lips and chin is a “moko” (tattoo) that speaks of her rank and hapū; and around her neck a “pounamu hei tiki” (jade pendant) gifted to her by her ancestors. Hinepau’s status makes her a prize. She is not a lowly slave who will be put to work but a “treasured virgin” eligible for aristocratic marriage.

The war canoe belongs to the turbulent tribes of the Waikato. On its way back from battles and skirmishes down south, the party has stopped on Whakaari to replenish supplies of food. Seabirds such as the tītī are plentiful. When they planned this sojourn they never imagined how bountiful the expedition would prove.

Hinepau is bound and carried back with care to the stronghold of the Ngāti Mahuta, in the Waikato, and offered to their giant chief Te Wherowhero. At first Hinepau is terrified. She has never seen a man this tall before. Long-boned and magnificent, Te Wherowhero looks like a god in his brilliant “kahu kura” (a red-feathered cloak). Hinepau understands all that is woven into the weft of this garment, for the rare kahu kura is a symbol of chiefly power. It connects to the god Tāne, father of the birds, and endows the wearer with the oratorial skills of the raucous kākā (a species of parrot), whose feathers adorn it. She knows that the kahu kura can also signify peace. Te Wherowhero is a warrior chief, who will eventually lead a confederation of tribes. But when he meets Hinepau he is simply a young man of promise: a rangatira approaching his prime.

Te Wherowhero sees their union as a chance to draw the peoples of Whakatāne and Waikato together. He sees also her youth and her beauty, and he wants her. He will sleep with her and they will have “tamariki” (children) together. Te Wherowhero tells his men that “she must not be defiled,” because when she is ready he will take Hinepau as his wife.

Several summers come and go before Hinepau is big with their child. Her time of confinement finally comes, and a woman, a “tohunga” (priestly midwife), is summoned to the hut away from the hapū where Hinepau is to give birth. Te Wherowhero waits, anxious to welcome his child into the world. He paces, he frets, he prays to the gods to save his precious young wife and their child. For once, his mighty strength is useless. There is nothing he can do. Te Wherowhero is in despair. Will there be no end to this terrible waiting?

Te Wherowhero’s three days of waiting for Hinepau to give birth ended with the most tragic news. His teenage wife, his first flowering of true passion, was dead. Their baby had survived: a girl who would be named Irihapeti Te Paea Hahau. Te Wherowhero was inconsolable, his heart broken by his loss. In memory of this terrible time he himself took an additional name — Pōtatau — meaning those who count the hours, to remember waiting for news of Hinepau. Names to Māori are like their moko, telling a story of their lives and their connections. Both his new name and the sight of Irihapeti as she grew reminded him of his first love and his first great loss.

Irihapeti grew up motherless among her father’s Ngāti Mahuta people. She belonged but didn’t belong, her birthright buried by bloodshed and time. Te Wherowhero, the great warrior chief, was often away fighting battles and exacting revenge. He would take more wives and produce more children. By the time it came to his investiture as King, her mother, a child bride long dead, was left off the list of official wives. Irihapeti Te Paea Hahau — a noble woman, a rangatira — was a princess without a bloodline to the throne.

Some inheritances could not be denied her, though. She would share three things with her father: a warrior’s spirit; a belief in the politics of marriage; and, ultimately, a profound faith in a monotheistic God. These were the treasures she carried with her: her taonga for life.

Irihapeti married at 16 years old. However, if the union she made with the tall, redheaded, 20-year-old Scotsman John Horton McKay began as a politically strategic alliance between Māori and Pākehā, then it would end as a love match. The respect and the love were mutual. She wore Pākehā women’s clothes to pass in the settler world of the 1840s for him, and he dressed in a Māori warrior’s cloak and carried an ornately carved spear for her. There is a photograph of him standing proudly — if a little incongruously — a white warrior. John Horton McKay lived as a Pākehā Māori, fluent and fluid in the way he moved between two languages and two cultures.

Like many mixed couples, they traded goods and supplies, opening a general store at the settlement of Putataka, which a few decades later would develop into the town of Port Waikato. Irihapeti was both entrepreneurial and astute. Their business — the business of trade between Māori and Pākehā — flourished, and so did their relationship. Their first child, Marianne, was born in 1838, when Irihapeti was 18 years old. Records show that Marianne was followed by at least 11 more children.

This was a bicultural marriage. Irihapeti raised her children to know the ways of Māori, while John Horton raised them as Scots. The McKay tartan was even adopted by the Kīngitanga Māori (tribal confederation) as an emblem of clanship and royalty.

Irihapeti would have understood all about strategic marriages, as her mother’s had been, and would have been conscious that her own brought two powerful peoples together, which should benefit its progeny, their descendants. She saw mission schools as a source of new knowledge and enrolled all her children. Education opened opportunities, creating pathways into the Pākehā world.

Irihapeti toiled long days and nights to keep their general store open and feed and clothe her children. Life was a cycle of pregnancies, domestic work and serving in their shop. But, like her father, she had a huge capacity for work, and she had her faith. When Anglican Bishop George Selwyn visited the settlement of Putataka, she had her children baptized at once.

While Irihapeti used old medicines and practiced Māori lore, her soul belonged to a Pākehā god and her heart to peace.

Sue discovered a photograph of Irihapeti in the National Library in Wellington. The date of the photo is circa 1860, and she is dressed in black. Irihapeti is a widow. The man who powered her waka, John Horton McKay, is dead. McKay’s watery grave was a swollen river he attempted to cross in an 1859 flood.

Irihapeti is in mourning attire. Her expression hides the agonies behind it. There is the loss of her husband and the grief of her father’s death in 1860, but also the angst of not knowing how she will support her 12 children, the last of whom is only a few years old.

Photographs like this one of Irihapeti, taken by the Burton Brothers, were syndicated. They were sent to other studios around the country where they were printed on postcards with facetious titles like “Queen Emma of the Thames” and sold to the general public. Maybe this exploitation is the price Irihapeti paid for a copy of her image? A picture of grief, a memorial to her father and husband.

Irihapeti would find salvation for a time with another Highland clansman, a Scotsman named Samuel Joyce. The consummation of this late marriage required a move for Irihapeti from her store at Putataka to Raglan. At the beginning of the 1860s, there were 424 inhabitants there, with a Māori settlement and pā across the harbor at Horea. Raglan had just changed its name from Whāingaroa and boasted just half a dozen houses, a tavern and a store.

The heat in this union, however, would quickly dissipate. Despite having a further three children with Joyce, Irihapeti’s marriage was neither a happy nor a productive one. Her second husband was a drinker, and his ways were profligate.

Irihapeti, a devout woman, born and bred among a people who were coming to see alcohol as the scourge of their culture, lived as long as she could with Joyce, then fled. Homeless and now destitute, she went to live with her adult daughter Clara, who provided Irihapeti with a refuge, but not a permanent home of her own.

While Irihapeti could accept the tragic loss of her beloved first husband and the misfortune of marrying Joyce, she would not accept homelessness in a land her people owned. The warrior spirit that had been her father’s, that knew the value of land and had fought in hand-to-hand combat for it, would not let her rest. She wanted what was rightfully hers. Her people had shaped the hills and valleys, creating terraced gardens and redoubts, felling trees for waka, clearing pathways and digging kūmara pits. The stories of her forebears could be read in each contour and plain.

Irihapeti’s battle would be waged in the land courts, where, in 1874, she had to prove to a hostile Pākehā authority that she was the unacknowledged first child of the late King Te Wherowhero. The land she was seeking had been confiscated by the British governor, Grey, on the false pretext that Waikato Māori might attack Auckland. Ultimately, a tribunal was established to decide what land would be returned, and to whom. Irihapeti took her case to court along with many others: a widow, a neglected wife, fighting single-handedly for the rights of her mokopuna. She would not be intimidated. She would not be overpowered by an unsympathetic system.

Irihapeti fought courageously and won her battle in the Land Court. In January 1874 she received Lot 470 in the Parish of Taupiri. She was buried close by with her “whanau” (family) on sacred Taupiri mountain in 1900, this strong woman having lived to 80.

Irihapeti’s gift to the world was her progeny: two marriages and 15 children, who were both Māori and Pākehā, people who internalized a struggle over land and culture and would have to find their own peace. The story of Irihapeti’s royal lineage would be lost to subsequent generations. One of many erasures: the generational shame of being Māori — the silences of language and culture that over time had left her whakapapa mute.

It was family research and Sue’s own endeavors that would uncover her remarkable heritage. Sue could finally confirm she was a princess, and I found a second tribe to carve, to match my own in the chess game of biculturalism.

This article was published in the Summer 2023 issue of New Lines’ print edition.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.