Listen to this story

The IUD was still dripping with blood when my gynecologist placed it in the palm of my hand. “I want you to hold it,” she said. “I want you to feel how small it is, and ask yourself whether you might be overreacting.”

As I looked at the small, T-shaped copper device she had tried, and failed, to insert into my uterus three times in a row, I had to admit that it was indeed quite small — roughly the size of the plastic floss pick I’d used on my teeth that same morning. Its size seemed disproportionate to the amount of pain I’d just felt. It had been excruciating, worse than anything I’d ever experienced (and I’ve been run over by a motorcycle). My cervix — whose existence I’d happily disregarded up until then — felt raw, like it had just been stapled.

Over the next month, though, I became convinced I had overreacted. Thousands of women (in this essay, women refers to people who have a uterus) have IUDs (the acronym for intrauterine device) inserted daily, I reasoned with myself. I decided to give it another go. My gynecologist wrote me a prescription for antianxiety medication, told me to take an Ibuprofen an hour before the procedure, and I went back to her office with a brand-new insertion kit.

Though I fainted halfway through and vomited in Parisian trash cans all the way back to my home, I was glad the insertion had worked this time. But I still could not understand why the procedure had, again, hurt so much.

Looking for answers, I turned to my friend Lucie, who trained as a general practitioner in neighboring Belgium. She asked me only one question: “Did they use the Pozzi forceps on you?”

I’d never heard of Dr. Samuel Pozzi before — or of his namesake forceps.

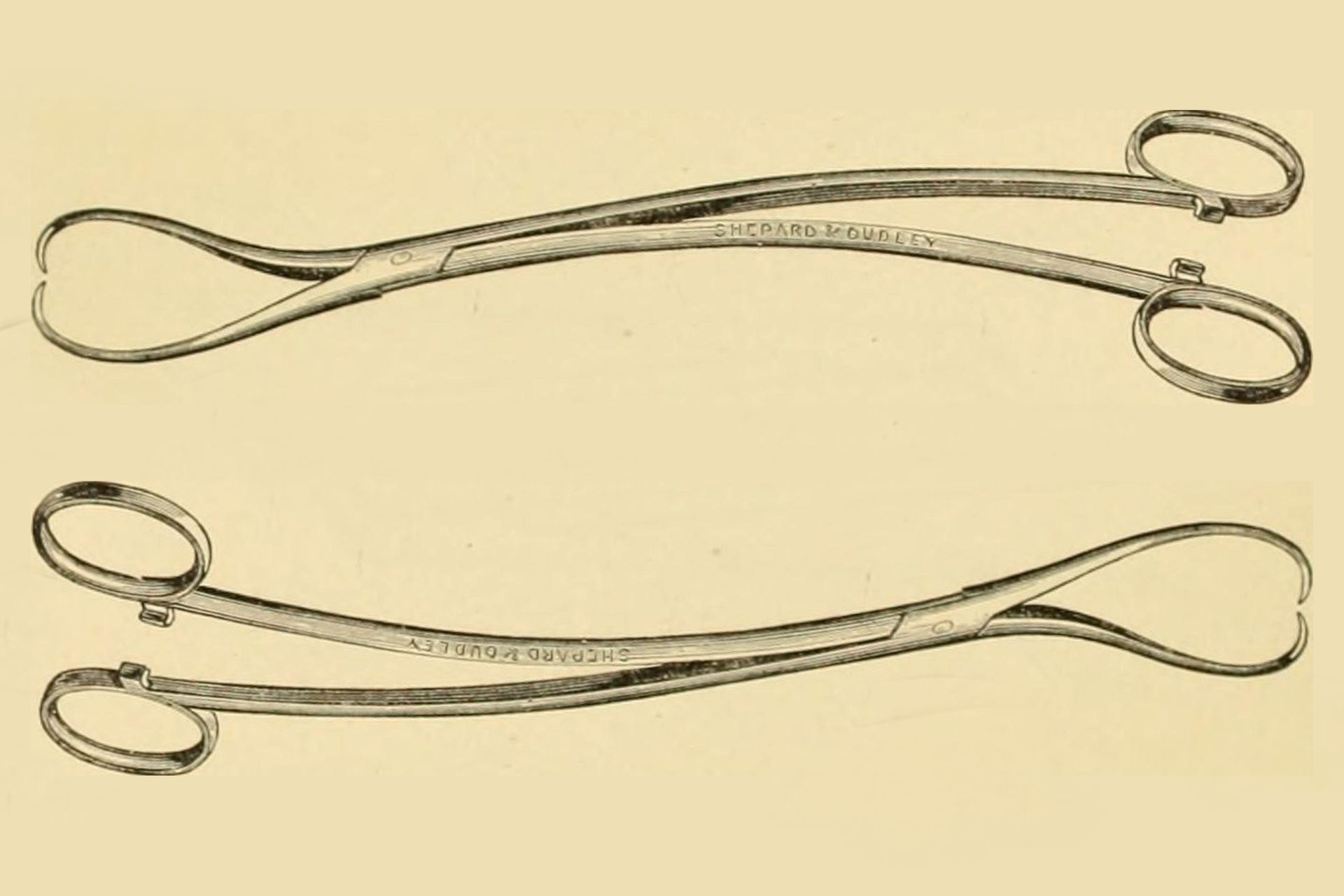

A quick call to my doctor confirmed that she had indeed used this instrument on me — but not to worry, she said: It had been routine in cervical procedures across the world for more than a century. On the social platform TikTok, I looked into the “IUD insertion” hashtag, where a 20-year-old with bubblegum pink hair and a couple of hundred followers showed me what my gynecologist had failed to: a metal tool shaped like a pair of scissors, with pointed tips curved inward, meant to grant easier access into the uterus. In the video, she used it to pierce, grab and pull at a silicon ball — a stand-in for my punctured cervix.

“That’s the ‘small pinch’ they warn you about prior to insertion,” historian Evan Elizabeth Hart told me: “the literal stapling of your cervix. Without anesthesia.” Hart specializes in the history of women’s health activism at Missouri Western State University. She’s not afraid to call this what it is — medical gaslighting.

Historically, women have been denied knowledge of and control over their own bodies by a patriarchal and paternalistic medical system, Hart explained. Women are led to believe that their pain is individual (easily fixed with an Ibuprofen) rather than systemic (requiring comprehensive change in both tools and practices). “The only way to challenge the status quo is to raise consciousness about the tools that are used on us and their complicated history,” she said.

The Pozzi forceps, or tenaculum — which had caused me so much physical pain during my IUD insertion — are a good place to start. In 1889, French surgeon Samuel Pozzi, inspired by an American Civil-War era bullet extractor, invented an instrument to ease gynecological exams and provide better care for women. One hundred and thirty-five years later, despite reports of pain, from “just a pinch” to debilitating, this tool continues to be used in IUD insertions and cervical exams worldwide and serves as a testament to the difficulty of challenging medical norms when it comes to women’s reproductive health.

The story of the tenaculum, and its inventor, begins, as many French things do, with a revolution.

Though historians have often described Pozzi as the “father of modern gynecology,” quick Google searches mostly bring up romanticized portraits of the “Love Doctor of Belle Epoque Paris,” as Parisian blog Messy Nessy Chic dubbed him. One French radio host portrayed him as “a friend and lover of the famous, who invariably seduced his patients with nimble fingers as suited for surgery as they were for the boudoir.” The flamboyant life of the Man in the Red Coat, immortalized by the society painter John Singer Sargent, and biographized by Julian Barnes, more often than not overshadows his own invention.

I decided to dig into the archives myself — namely, Pozzi’s foundational “Treatise on Gynecology,” his private letters, and French press clippings that told the story of his crusade for women’s health.

Pozzi was born in 1846 in southwestern France, to a family of Swiss and Italian descent. He grew up surrounded by women — his mother, aunt and grandmother raised him and his five sisters. His father, a local pastor, was largely absent. At the age of 10, he lost his mother to tuberculosis and his youngest sister to typhoid fever. Unsurprisingly, young Pozzi set his sights on medicine, encouraged by his cousin, Alexandre Laboulbene, who served as Napoleon III’s personal doctor in Paris.

“The Siren,” as his peers nicknamed him, was a handsome adolescent with a magnetic personality and a taste for the finer things; but what really set him apart was his work ethic and his passion for healing. By 1864, Pozzi graduated at the top of his class and made his way to Paris. Four years later, he began his surgical residency at the Hopital de la Pitie, home to the capital’s poorest and sickest residents (members of the upper class were still treated at home).

There, he discovered that childbirth was the leading cause of death in women, and that diseases affecting women were overwhelmingly fatal. Pozzi encountered monstrous ovarian cysts, uterine cancers, venereal diseases and puerperal fevers, and was baffled by his teachers’ inability to help. They were, as he would later write in his “Treatise on Gynecology,” “stuck in a constant struggle between medicine and routine,” in a country that, unlike neighboring Germany and England, had yet to make gynecology into a specialty. France was falling behind.

In July of 1870, war tore Pozzi away from his beloved hospital and his early musings on women’s health. His country, determined to reassert its dominant position in continental Europe, had declared war on Prussia. Pozzi’s mentors were sent to the front lines to tend to the empire’s soldiers, and the medical school was shut down. Eager to serve, and even more eager to learn, Pozzi volunteered as a medic.

Much of his surgical apprenticeship took place on the front lines, tending to mutilated bodies, draining infected wounds, amputating shredded limbs and treating bullet wounds. Americans had come up with a new bullet extractor a few years earlier on the battlefields of the Civil War: a set of straight forceps with pointed tips curved inward, which allowed medics to easily grab, hold and pull foreign objects from their patients’ bodies. It was, as Pozzi would later write, “the very best of gripping instruments.”

Upon his return to Paris after the war, Pozzi finished medical school with top marks. After successfully defending his thesis on uterine tumors, he was made associate professor at the age of 29, and quickly became one of Paris’ most sought-after surgeons. In his free time, according to his biography, he translated Charles Darwin, wrote poetry, befriended the Proust brothers, seduced Sarah Bernhardt and read foreign medical journals.

Unlike most of his peers, Pozzi spoke both English and German, and he looked abroad to modernize French gynecological practices. In 1876, he met pioneering surgeon Dr. Joseph Lister at a British Medical Association congress in Scotland and brought his recommendations back to France: antiseptic surgery and preventative healthcare. In Germany and Austria, he found that his peers had started implementing routine checkups for their female patients, rather than wait for surgery to become necessary.

In 1883, Pozzi was named head surgeon of the Broca Hospital in Paris and decided to apply these revolutionary principles to his own service. One year later, he had a brick and wood barracks built in the hospital’s back garden. There, he opened the very first French gynecological department — a “red-letter day for Parisiennes one and all,” according to Le Figaro newspaper.

In the interview that followed with the French daily, Pozzi stated his goal for his new service: “to alleviate women’s suffering.” Pozzi had his modest barracks decorated with colorful frescoes, gifts from his many artist friends intended to heal the minds while he healed the bodies. Like everything else in his hospital, the frescoes could be washed with phenol solution to prevent the spread of diseases. Women, rich and poor, were examined with gloved hands and warmed speculums.

The women’s pages of the Parisian literary periodical Gil Blas sang Pozzi’s praises:

He is beloved by women, for he seems only to be concerned with their sufferings, imaginary and real; for he appears to them as a sort of comforter and magician, penetrating them, understanding them, supporting them; for his way of caring for them, delicate, flexible, reassuring; and, finally, for his inventions.

One of these inventions was a new type of tenaculum, which Pozzi premiered at the 1889 Paris World Fair.

At a time when radical hysterectomies were still the norm to deal with cysts and other uterine diseases, this tool allowed doctors to gain access to their patient’s uterus through the cervix. This meant that they could treat their ailments in a less invasive manner.

Pozzi had obviously been inspired by his time as a field medic two decades prior. In his revolutionary “Treatise on Gynecology,” published one year later and soon translated into five languages, he described his new tool in the simplest of terms, as “a forceps (which is none other than the American bullet extractor).”

As for its use, he wrote the following: “The tenaculum only makes two insignificant stings, which cause no harm and which barely bleed.”

More than a century on from the invention of Pozzi’s field-changing device, my experience was markedly different. Pozzi’s tenaculum had caused me great harm, and much bleeding.

When asked about the disconnect between Pozzi’s writings and my own cervical manipulation, Martin Winckler, a French doctor who retired to write novels and essays about women’s health, told me that I’d been looking at the problem all wrong. The issue was not so much the tool, but what it was used on.

“Pozzi was operating under a false assumption,” Winckler said, “that the cervix was devoid of sensory nerves, and that it could be pierced and prodded without consequence.” In reality, specialists have since discovered, the cervix is the locus of no less than three different nerves: the pelvic nerve, the vagus nerve and the hypogastric nerve. It can very much feel pain, and cause its owner large quantities of it.

And yet the use of the cervical tenaculum has gone largely unquestioned since its inception 135 years ago, in large part thanks to its famous inventor. In 1901, Pozzi was appointed as the very first French Chair of Gynecology, which had been established for him. His “Treatise on Gynecology” would be required reading for generations of surgeons in his home country, and his invention spread across the world. In the annals of French medicine, he is still remembered as the founding father of gynecology.

Though Winckler is a firm believer that “gynecology shouldn’t have a father,” it has several, and their hold on contemporary gynecology is still strong. Much in the same way that James Marion Sims’ speculum has stood the test of time despite its inventor testing it on slaves, Samuel Pozzi’s tenaculum continues to be sold, taught and used. Patriarchal medicine, and a general disregard for female pain, have removed the need for an improvement — until recently.

In the wake of global discussions around the gender pain gap in medicine, women have started speaking up about their painful IUD insertions. They, too, say it feels like death.

In response, ob-gyns have begun experimenting with pain relief options — from meditation to hypnosis and local anesthesia — and developing less painful procedures. Dr. Winckler used what he calls “the torpedo method” (yet another battlefield legacy) in which the gynecologist inserts the IUD alone through the cervix, rather than the larger IUD insertion tube. “This renders Pozzi’s forceps unnecessary in 9 out of 10 insertions,” Winckler said.

As for the object itself, several tech start-ups geared towards women’s health have given the cervical tenaculum a much-needed redesign. Swiss gynecologist David Finci, who felt “ashamed” of using Pozzi’s flesh-piercing instrument on his patients, turned to his brother Julien, a medical device engineer. Together, they founded Aspivix, and designed a suction-based cervical retractor, which adheres to the cervical tissue without penetrating it.

Though the co-founders are, again, male, they have managed to create a female-friendly solution for modern gynecology, tested and approved by a slew of female practitioners and patients. Cleared for U.S., U.K. and EU markets, Carevix promises to “Remove the pain from ‘just a little pinch’ gynecological procedures.”

When I began writing this story, I was fully prepared to despise Pozzi. I was convinced that the man who had designed the tool that had hurt me so badly could only have been a sadist. What I found instead was a forward-looking surgeon who, though he certainly slept with many of his patients, was deeply committed to helping women.

I have to believe that Pozzi would have wanted his 21st-century peers to set aside their tenaculums and make the move to atraumatic devices. Perhaps had he lived long enough, he would have found a better way himself.

But Pozzi’s life was cut short on June 13, 1918. Maurice Machu, a former patient who Pozzi had treated for an enlargement of the scrotum, came to his office to complain that his — very painful — surgery had made him impotent. Pozzi disagreed, suggesting he was “suffering from a nervous complaint.” Enraged, Machu shot him three times in the chest, before turning the gun on himself.

As things stand today, Pozzi’s tenaculum is still used in most gynecological offices across the world. And it looks exactly the same today as it did on the battlefields of the Civil War and at the Paris World Expo in 1889.

At Duke University’s History of Medicine Collections, photographer Lindsey Beal held one of the earlier models in her own hands. In 2018, she set out to document vintage gynecological and obstetric instruments in medical libraries across the United States. She told me she had expected to come across gruesome tools; instead, she encountered instruments she had seen before. So too had most of her friends, and anyone who had interacted with the medical establishment regarding a uterus.

When I asked her what she thought about Pozzi’s tenaculum, she said: “It looked right at home in a medical archive. Not so much in my doctor’s office.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.