On Dec. 29, Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States, passed away. News of the politician’s death in Georgia first reached me in Virginia, where I was spending the holidays with family. A cause for national mourning, Carter’s departure inspired no shortage of touching tributes, but it was the passing of another person that very same day that moved me to tears. Ahmad Adawiya, an artist I never had the chance to meet but came to know over the course of the past decade, left us at the age of 79. That afternoon, the words of one Egyptian author succinctly captured what the iconic performer meant to many listeners. “He was the very voice of Cairo, my Cairo,” Youssef Rakha wrote on Bluesky. “His music is everything.”

Rakha, in this regard, was not alone. The posts of friends and strangers alike, from across the Arab world and thousands of miles away, flooded my social media feeds. Whether sharing Adawiya’s memorable songs, embedding interview clips highlighting his historic career, or uploading photographs of him performing over the past five decades, eulogies on Facebook, X and Instagram collectively recognized Adawiya as an exceptional artist who made an extraordinary impact, altering the course of Egyptian music.

Absent from many of these commemorations, however, were the obstacles Adawiya had to overcome en route to becoming a legend. Praised by many people after his passing, the artist was regularly condemned by critics during his lifetime. Excluded from the traditional routes to musical success, Adawiya would instead turn to a new medium to make his name known. The humble cassette, a technology we now seldom contemplate, presented the singer with an opportunity not available to previous generations of performers: to reach a mass audience beyond the radio’s guarded gates.

Born in the summer of 1945 in Minya, a governorate that has produced no shortage of Egyptian luminaries, from the feminist Huda Shaarawi to “the dean of Arabic literature” Taha Hussein, Adawiya, like many other people in pursuit of a better life, made his way to Cairo at a young age. In sharp contrast to several of his contemporaries, who mastered their craft in the capital’s elite conservatories, he learned how to perform on a road known for its musicians. On Muhammad Ali Street, in the years following the rise of the “Free Officers” — a group of military men who executed a bloodless coup in the summer of 1952, sending King Farouk sailing for Europe and producing Egypt’s next three presidents — Adawiya interacted with several leading singers, including Mohamed Rushdi and Shafiq Galal. These exchanges often unfolded in cafes, where Adawiya worked as a busser to get by. When not clearing tables, he gained experience playing multiple instruments, including the reed flute and tambourine. But it was his voice that would open new doors, including one to a celebrity’s home.

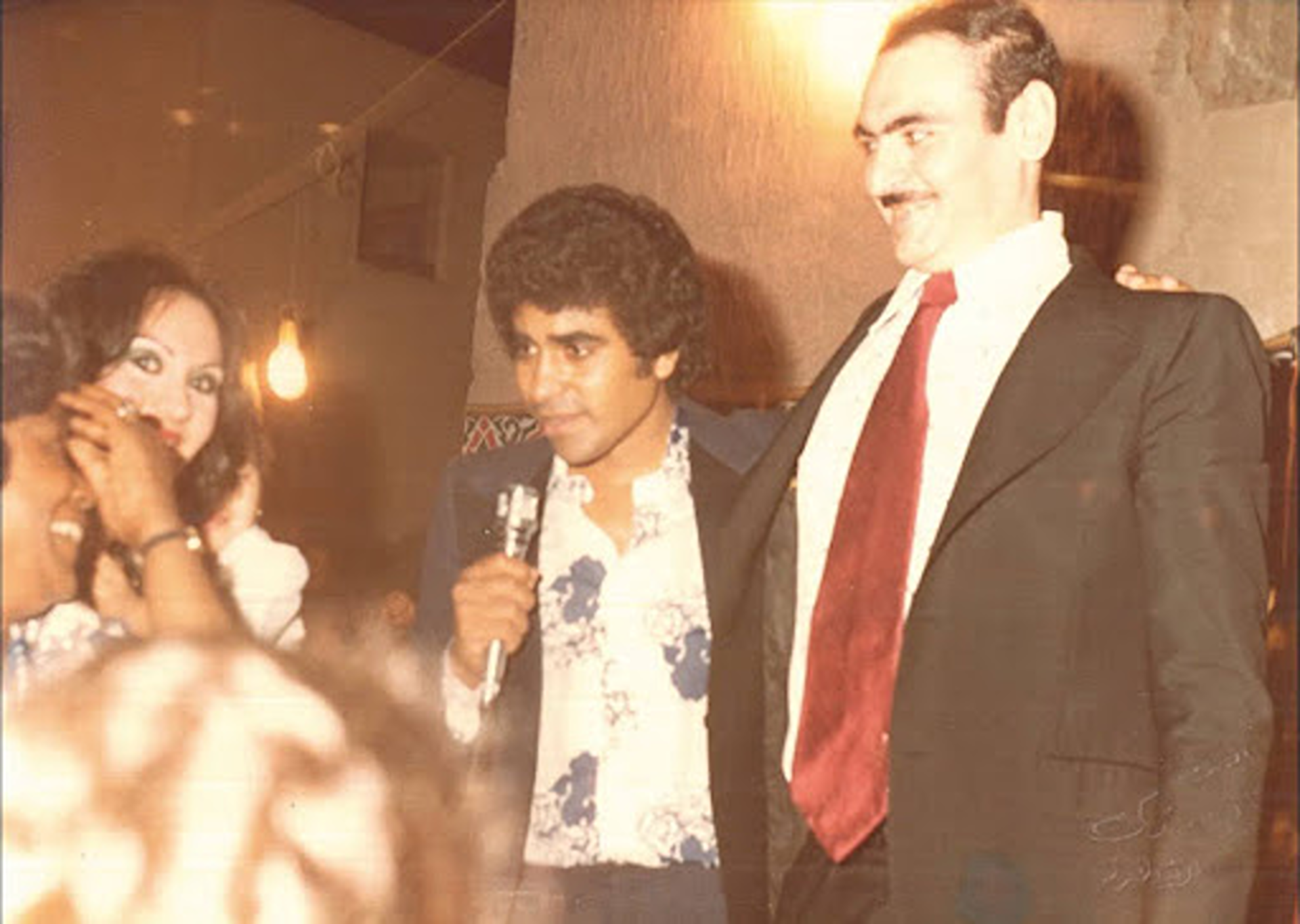

Sharifa Fadil, a fellow artist and future nightclub owner, regularly held parties at her house, where singers entertained influential people. At one such gathering, in 1972 — the year before Egypt’s president, Anwar Sadat, went to war with Israel — Adawiya sang and crossed paths with a guest named Amin Sami. Sami invited him to perform at “Arizona” nightclub on al-Haram Street, and it was inside one of the thoroughfare’s many recreational haunts, with the pyramids looming nearby, that Adawiya was noticed by Mamun al-Shinawi. A lyricist from Alexandria who would work with some of Egypt’s biggest stars, al-Shinawi at the time served as an artistic adviser for a new record label eager to make its mark.

Sawt al-Hubb (The Voice of Love) was on the brink of bankruptcy by the time al-Shinawi heard Adawiya singing one day on an al-Haram Street stage. The chance encounter changed both men’s lives. With al-Shinawi’s support, Adawiya recorded the first of several hits on a cassette for Sawt al-Hubb in 1973. Selling an estimated 1 million copies, and saving the label from financial ruin, “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu” was a resounding success. The single, whose baby-talk title defies translation, signaled a welcome departure from other music and captured the attention of a huge audience with its catchy beat, use of colloquial Arabic and the everyday story it told.

According to one account, the inspiration for the song was a mundane moment years earlier. Khalil Mohamed Khalil, a working-class lyricist from Cairo who went by “al-Rayes Beera,” was invited to the house of a friend to help him and his wife reconcile. When preparing tea for their guest, the wife left their baby by Beera’s side. Upon hearing her son begin to cry, she instructed him from the kitchen to “give the baby to his father,” who, still angry with his wife, did not act, prompting Beera to tell them to “pick up the baby from the floor.” After the couple started seeing eye to eye again, the story goes, Beera left the house with a new song in mind. “Al-Sah al-Dah Ambu” was born. The tune revolves around two people seeking to quench their “thirst,” a baby — much like the one Beera witnessed — crying on the ground waiting to be picked up and a man, whose nights have “grown longer,” looking for a lover, “a beauty on a budget.”

Shortly after recording this song, which features a sparse ensemble, opening with percussion, tambourine and trumpet, Adawiya traveled to Libya, only to discover that “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu” was all the rage when he returned.

“Salamitha Umm Hassan” (“Get Well Soon Umm Hassan”) followed, with “Haba Fuq wa Haba Taht” (“A Little Bit Up, a Little Bit Down”) and “Kullu ala Kullu” (“Everything on Everything”) joining the artist’s expanding repertoire in 1974. Whether booming in taxis or blasting in nightclubs, playing at weddings or in barber shops, these cassette tracks attracted Egyptians from all walks of life. Short, infectious and full of energy, with crisp vocals and pared-down ensembles, the recordings contributed to a nation’s changing soundtrack and the formation of a new musical genre: shaabi. Sharing the same Arabic root as “al-shaab,” (the people), shaabi music was grounded in daily life and used the Arabic Egyptians regularly spoke. On these fronts, it departed radically from the dominant singing style of the day.

“Enta Omry” (“You Are My Life”), a song by two established, even legendary, artists, shows the contrast. Known as the “Star of the East,” Umm Kulthum emerged from a village to take Cairo’s commercial recording scene by storm in the roaring ’20s. A master of tarab, a kind of music that literally means “enchantment,” she frequently left listeners in a state of ecstasy. “The Musician of Generations,” Mohammed Abdel Wahab — actor, singer, and composer — was an innovator who integrated Arab and Western musical cultures. The outcome of their much-publicized collaboration, which Egypt’s president at the time, Gamal Abdel Nasser, helped facilitate, premiered in a theater in 1964. The poetic song spans more than an hour in length. Accompanied by a large ensemble, featuring more than a dozen string players, Umm Kulthum addresses a beloved who changed her life, from one that was “wasted” before they met to one where she fears how little time they have left. “You are my life, whose morning began with your light,” she sings at the end of the chorus, drawing out each word. Following its debut, which was broadcast live, leading at least one other Arab country’s national station to cancel its nightly news program to stay with the concert, “Enta Omry” was played several times a day on Egyptian radio — a privilege Adawiya and his very different music would not enjoy. It aired so often, in fact, that Umm Kulthum and Abdel Wahab personally requested the number be broadcast less.

In 1976, Adawiya, now a household name, achieved the accolade of making the top-selling tape in all of Egypt. But he was nowhere to be found on Egyptian radio. When officials from a series of leading stations publicly ranked singers in a popular magazine in 1975, acknowledging how they afforded the most airtime to “first-class” artists like Umm Kulthum and Abdel Wahab, Adawiya’s name was not even part of the conversation. Yet he was everywhere, and most Egyptians were familiar with his music, with cassettes carrying his voice near and far beyond the reach of cultural gatekeepers who sought to stifle him.

The dawn of state-controlled Egyptian radio can be traced back to the spring of 1934, when independent stations, operated by individuals, were compelled to close by political authorities. After amateur broadcasters fell quiet, the Egyptian government’s station issued its inaugural broadcast. To ensure only the “correct” content reached the masses in the years ahead, radio officials relied upon two committees to screen lyrics and recordings, respectively. If a song received their approval, stations could then decide if they wished to play it or not. The radio’s selectivity was a source of pride, its exclusivity regarded as essential. Officials viewed the technology as “a school without walls for all people” and pledged not to damage “public morals and dignity.” Adawiya was denied access to the radio by these committees. What these critics found so objectionable about his music was the very reason for its popularity among the masses.

In “Haba Fuq wa Haba Taht,” the singer introduces a man looking up at a gorgeous woman, only to have his flirtatious glances go unnoticed. “Gorgeous lives upstairs and I live down below,” Adawiya sings at the start. “I looked up with longing, my heart swayed, and I was wounded. Oh people upstairs,” he proceeds to plead, “go on and look at who is below. Or is the up, not aware of who is down anymore?” Adawiya asks at the end of the first refrain. For some, the catchy number captured an everyday experience. For others, it was the epitome of “vulgarity,” sexually suggestive and devoid of deeper significance. For still others, the song spoke to growing class divides. This reading was one critics quickly dismissed. Adawiya, they argued, was the embodiment of Egypt’s economic ills, not one of its shrewd interpreters. Such musical numbers, from the perspective of cultural gatekeepers, had no part to play in the making of model citizens over state-controlled airwaves.

In the words of one preacher, Abd al-Hamid Kishk, Egyptian youth would be better off studying poetry than listening to his “tasteless” music. Adawiya’s inclusion in Kishk’s spirited sermon is telling. A clear critique of the artist on the one hand, the same remarks also indirectly evidence Adawiya’s growing popularity. Why, after all, attack an artist no one knew? Without radio, Adawiya would gain fame through another, now largely forgotten medium and, through it, would become a force. By the late 1970s, one Egyptian journalist would ask: “How can we escape from Adawiya’s school?” After being denied admission to the radio’s “school,” Adawiya became one in his own right.

Audiocassettes, introduced in Europe in 1963, empowered an unprecedented number of people in Egypt to participate in the creation and circulation of culture. Cultural consumers became cultural producers for the very first time. Whether finding its way to cities and villages with Egyptian migrants returning from Iraq, Libya and the cities of the Arabian Gulf on planes, in cars and atop boats in the midst of the oil boom — or originating from local factories and licensed agents that partnered with international manufacturers like Sony and Samsung — cassette technology became a key object in the making of the “modern home” and a coveted commodity as a broader culture of consumption gained ground under Sadat. Following the 1973 war with Israel, which resulted in a military stalemate but represented a political victory for Egypt’s president, Sadat announced the infitah, or “opening up” of Egypt’s economy. This development signaled a shift from state-sponsored socialism to capitalism. Mass consumption boomed as a result, and cassette culture flourished alongside it.

Portable, usable and affordable, cassettes and cassette players did not simply join other mass mediums, like records and radio; they became the media of the masses. The everyday technology provided countless people with a powerful tool to circumvent censors and state-controlled channels of cultural production, including the radio. The cassette, in this regard, facilitated many of the changes that we routinely attribute to social media, and it did so decades earlier. At a distance from professional studios, anyone could record their voice, copy it and reach a wider audience with the push of a button. This ability was revolutionary.

Much to the ire of local gatekeepers, many Egyptians enthusiastically embraced the creative power of audiotapes. Among the individuals to contribute to Egypt’s infinitely richer soundscape, courtesy of cassettes, was Adawiya, whose voice rang out from cars, cafes and homes. No longer limited to live performances at nightclubs, weddings or other venues, the singer would surface at the center of national debates on the “downfall” of music.

In the summer of 1977, Adawiya released yet another hit, “Bint al-Sultan” (“Daughter of the Sultan”). As was the case with his first chart-topper, “al-Sah al-Dah Ambo,” the theme of “thirst” returned once more, only this time no baby was involved. In the tune, which traveled widely on tapes, the singer engages a woman holding water on the Abbas Bridge. Spanning the Nile and facilitating its crossing on foot and in cars, this setting was a familiar landmark to many in Cairo. “Oh daughter of the sultan,” Adawiya sings at the start, “take pity on this poor guy. The water is in your hands, and Adawiya is thirsty.” In the verses to follow, the artist pleads with the beauty on the bridge, a woman whose words are like “vitamins,” to quench his thirst by giving him the water she holds. Like her, we are told, this liquid is “sweet.” The flirtatious song concludes with a series of shoutouts, along the lines of those we might hear today’s artists offer at a concert. After acknowledging his love of Alexandria, home of Cairo and all the “Arab countries,” Adawiya recognizes communities across Egypt, from the people of Ismailia and Sharqia to Mansoura and the Said, prior to pleading for more water.

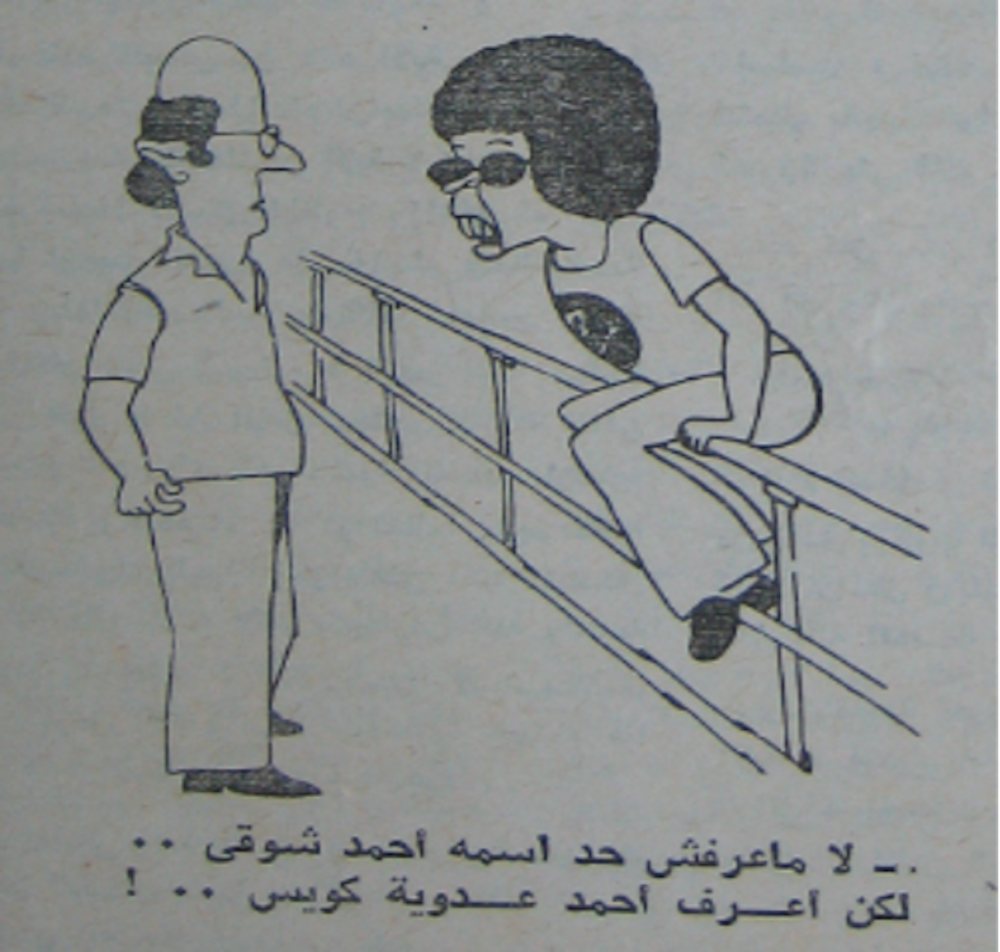

The same year that “Bint al-Sultan” debuted, Ruz al-Yusuf, an influential weekly magazine covering a wide array of cultural affairs in Egypt, published a sketch speaking to the artist’s growing notoriety. In the black-and-white drawing, an Egyptian youth, sitting on a railing, perhaps along a Nile overpass not unlike the one in Adawiya’s hit song, engages an older man in conversation. “No, I don’t know anyone by the name of Ahmad Shawqi,” he asserts, referring to one of Egypt’s literary giants — whose words served as lyrics for both Umm Kulthum and Abdel Wahab — “but I do know Ahmad Adawiya well.” The young person’s awareness of Adawiya and ignorance of Shawqi, “the prince of poets,” elicits concern, if not disgust, on the face of their more senior compatriot, capturing two common responses to Adawiya’s music: enjoyment and anxiety. Illustrators and journalists, to be certain, were not the only ones to take a critical stance toward Adawiya. Fellow artists, who stood to benefit from silencing him, joined the fray.

In the fall of 1977, the well-known singer and actor Muharram Fuad strolled into a casino in Alexandria known for playing Adawiya’s hits. Fuad had starred alongside Souad Hosni, “the Cinderella of Arab cinema,” in “Hassan wa Naima,” a 1959 Egyptian adaptation of “Romeo and Juliet,” and proceeded to build a prodigious catalog of countless romantic and nationalist songs, which could not have been farther from the grounded, spirited and suggestive aesthetic of Adawiya, whom he was currently hearing in the casino. Fuad, it is safe to say, would have been easily recognized by those present, and upon hearing one of his contemporary’s tracks, he insisted that “foreign music” be broadcast instead. This demand displeased the casino’s patrons, and Fuad was asked to leave the premises, a request the celebrity no doubt found infuriating.

What pushed the established artist to try to suppress Adawiya? A conflict two months earlier might have played a part. A writer, who penned a song for Fuad, provided Adawiya with the same lyrics before Fuad could record them. The author’s change of heart, if upsetting, was understandable. Adawiya’s albums flew off the shelves, and piracy, a popular practice that proved impossible to police, expanded their reach further still. Such counterfeit productions carried Adawiya’s voice well beyond the bounds of official releases, making it possible for people from Alexandria to Aswan to listen to his music.

Following this casino confrontation, Fuad would advocate for stricter censorship to “improve” Egyptian music. Three years later, he proposed the creation of a “cassette room” where a music adviser would accompany artists while they were recording. One of many efforts to rein in Egypt’s vibrant cassette culture and to reduce the intense competition faced by state-controlled recording labels, including Fuad’s, this vision never came to fruition. Countless voices, including Adawiya’s, continued to resound.

Adawiya’s popularity was a matter of both context and content. On the one hand, he stepped into a void left behind by beloved artists. Farid al-Atrash, “The King of Oud” who died in 1974; Umm Kulthum, “The Voice of Egypt” who died in 1975; and Abdel Halim Hafez, “The Son of the Revolution” who died in 1977 all passed away within a few years of one another. But in addition to the space they left, Adawiya’s music spoke to ordinary, working-class people in the colloquial Arabic they used on a regular basis. Rather than trying to refashion Egyptians, his songs animated their shared experiences. In the now classic track, “Zahma ya Dunya Zahma” (“Oh Crowded World”), Adawiya sings about congestion. In lieu of identifying particular places, as he did in “Bint al-Sultan” with the Abbas Bridge, he addresses a reality in many Egyptian cities that, in the case of this number, prevents him from meeting up with a woman. “Oh crowded world,” he sings, “crowded and loved ones lose their way.” “Crowded, and there is no longer mercy,” his voice soars, describing a chaotic scene he compares to “a saint’s festival without a saint.” Notably, Adawiya neither aspires to bring about order to this unruly terrain nor is he removed from it. He is immersed in this crowded world, which Egyptian listeners know all too well. “Zahma ya Dunya Zahma” proved to be so popular that its title became a catchphrase.

Those who found meaning in such songs, music deemed “meaningless” by critics, were routinely the subject of public ridicule. Despite eliciting the anger of some, though, Adawiya’s art engendered a more pragmatic response from other elites.

Abdel Halim was an eminent artist known for his romantic and patriotic songs, which continue to occupy a special place in the memories of many listeners today. In 1942, he, like Adawiya shortly after him, moved to Egypt’s capital to pursue his dreams. Once there, however, their paths diverged. Abdel Halim perfected his artistry not on the street, but in prestigious establishments. Graduating with degrees from the Arab Music Institute and the Higher Institute of Music Theater, he briefly taught music to children, before auditioning for state-controlled Egyptian radio. He passed the screening committee’s test and also connected with one of its kingmakers, Abdel Wahab, who became his mentor. Following the end of Egypt’s monarchy and the rise of Nasser, who became a larger-than-life leader and one of the performer’s personal supporters, Abdel Halim’s career took off. He went on to enjoy close relationships with political authorities, whom he supported, and cultural gatekeepers, who endorsed him. And recently, he popped up in eulogies for Adawiya in a surprising way.

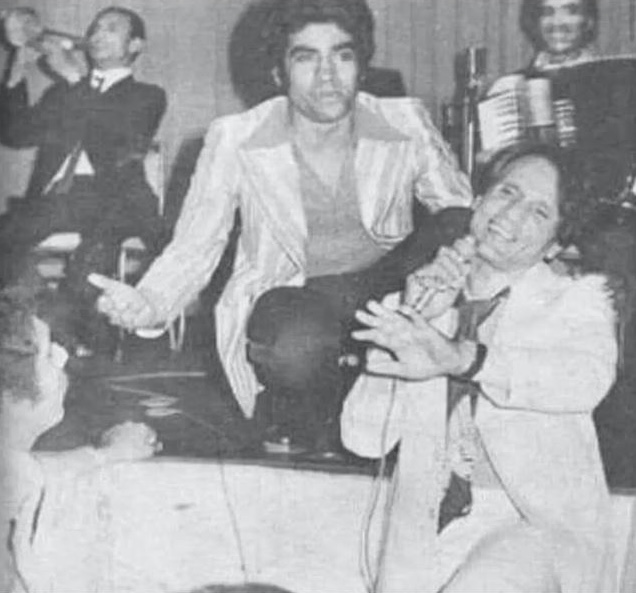

An online image has Abdel Halim standing in the foreground of what seems to be some sort of public performance, gleefully singing and waving his hand in the air as a young Adawiya, crouched down behind him, arms extended wide to his sides, engages the crowd from a stage. In the background, two instrumentalists support the entertainers on a trumpet and accordion. This curious scene raises no shortage of questions. What kind of music, exactly, is Abdel Halim singing? Why are the two performers together? And how did this black-and-white image come to be in the first place? Captions accompanying the grainy picture on social media sites offer little in the way of answers.

This image, it turns out, originated from an event nearly five decades ago. Toward the start of 1976, Adawiya took his talents across the Mediterranean to the Omar Khayyam nightclub in London, a venue that catered to visitors from the Middle East and members of the region’s diaspora. Abdel Halim, with business interests in mind, followed. In England, he tried to entice the artist in residence, who had listened to him growing up, to join Sawt al-Fann (The Voice of Art), a recording label he co-managed with none other than Abdel Wahab. He discussed a five-year exclusive contract with the star, only to have Adawiya’s label counter these terms. Less than two weeks after word of this proposal spread, Ruz al-Yusuf published the photograph that wound up cropped on social media posts commemorating Adawiya over the past few weeks. A caption joining the original image adds a key detail: Abdel Halim is singing “al-Sah al-Dah Ambu.” This picture created quite a commotion, with critics claiming it was evidence that Abdel Halim approved of Adawiya’s “vulgar” music. In response to this accusation, Abdel Halim denied the episode ever occurred, an instance of “fake news” long before the arrival of social media. In addition to being an amusing anecdote, this forgotten occurrence speaks to the fraught position occupied by Adawiya in Egyptian society at the time. An established singer felt the need to deny evidence of singing his music. It was one thing for Abdel Halim to personally enjoy Adawiya’s songs and another for him to confirm he did so in such a public manner.

Since the turn of the century, Adawiya’s undeniable popularity has continued to endure and evolve. When I was conducting fieldwork in Egypt for my first book, a history of the country’s cassette culture, the mere mention of his songs in the 2010s produced smiles, while recordings of them resulted in sing-alongs. Such exchanges became so commonplace that I grew to expect them. One thing I did not anticipate, however, was coming across the artist’s cassettes on the shelves of a state-controlled recording label in Cairo, whose gatekeepers, decades earlier, strove to combat the very tapes it now sold. During an outing to one of Sawt al-Qahira’s downtown branches in 2016, I saw Adawiya’s albums alongside those of Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim and other state-sanctioned stars. How did this happen?

One reason for this development could be heard nearby, where a new musical genre, mahraganat (literally “festivals” in Arabic), rang out from a curbside kiosk just around the corner. Like Adawiya, its artists sing about everyday issues in ordinary language and have been accused by critics of “polluting public taste” and “endangering society.” One elected official went so far as to claim that mahraganat constitutes a greater threat to Egyptians than COVID-19. This comment, made in 2020, followed a ban on the genre’s public performance by the Musicians’ Syndicate, a state-affiliated entity tasked with licensing artists in Egypt. A Valentine’s Day concert in Cairo Stadium, starring Hassan Shakosh, immediately preceded this nationwide crackdown. At the show, Shakosh sang not to “the daughter of the sultan,” as Adawiya did more than four decades earlier in “Bint al-Sultan,” but to the girl next door. In “Bint al-Giran” (“The Neighbor’s Daughter”), which features electronic rhythms generated by software in place of an ensemble, Shakosh expresses his affection for the beautiful woman next door and confesses how heartbroken he would be without her. “If you leave me, I’ll hate my life,” he declares. “I’ll be lost and won’t find myself. I’ll drink alcohol and smoke hashish.” For the head of the syndicate, Hany Shaker, who studied music at a prestigious conservatory in Cairo and performed no shortage of romantic songs amid Adawiya’s meteoric rise, this verse was unacceptable. Mahraganat needed to be contained.

The ban imposed by Shaker, however, could only accomplish so much in an age of streaming platforms and flash drives. Once a common sight in cabs and personal cars across Egypt in the early 2000s, cassette decks have been replaced by USB ports that bring mobile music libraries to life. The purported “vulgarity” of newer performers like Shakosh, whose direct lyrics and catchy beats blend electronic elements with hip-hop and shaabi music pioneered by Adawiya, has motivated even former detractors of the artist to see him in a more favorable light.

In the early 1990s, the Ministry of Culture in Egypt published a poster titled “A Hundred Years of Enlightenment.” Based on a painting by Salah Inani, the director of a government-sponsored gallery in Cairo, it serves as a “who’s who” of Egyptian culture. Authors such as Naguib Mahfouz, Taha Hussein and Yusuf Idris; actors such as Yusuf Wahbi, Naguib Rihani and Zaki Tolaymat; and musicians, including Umm Kulthum, Abdel Wahab and Abdel Halim, all make an appearance while the work’s title suggests an intimate relationship between culture and the crafting of model citizens. Adawiya, notably, is nowhere to be found in the painting-turned-poster, one of many omissions that has motivated my scholarship on Egypt.

Who is remembered, by whom and to what ends, are things I have found myself thinking through a lot recently, as I take steps to make my private collection of cassette recordings public in a digital archive later this year. Some of the voices on these cassettes are well known, but many enjoy little to no presence on streaming platforms, their talent confined to tapes that have yet to make the leap online. In building this digital archive, I am determined to show the richness of Egypt’s cultural heritage, which is so much more than those who appear in “A Hundred Years of Enlightenment.”

On this front, I am not alone. Multiple initiatives are underway to archive acoustic culture across the Middle East. One of these undertakings is Syrian Cassette Archives. Launched by Yamen Mekdad and Mark Gergis in 2022, this project preserves Syrian culture and reorients many discussions of the country’s history that reduce it to conflict. Alongside Syrian Cassette Archives, we have the Palestinian Sound Archive. A few years ago, in his hometown of Jenin in the West Bank, Momin Swaitat came across 12,000 cassettes covered in dust. Ranging from revolutionary anthems to wedding music, the tapes form the foundation of a digital archive in the making that counters the erasure of Palestinian culture. Joining these endeavors is a fanzine devoted to none other than Adawiya, whose cassettes have been digitized by Gary Sullivan. Together, these projects shed new light on the history of music and invite us to reimagine the very shapes that archives might assume. The future of these exciting undertakings is unclear, but one thing is beyond doubt. In addition to making a wide array of materials more accessible, these platforms will make new stories about the past possible.

This year, I had hoped to finally cross paths with Adawiya in Cairo. Although this meeting will not take place now, I find comfort in knowing that I can play his cassettes when sharing a meal with others going forward. Having once enabled Adawiya to reach a wider audience when critics strove to silence him, these old tapes will continue to introduce his voice to new listeners. One way of ensuring that his legacy lives on, these future exchanges, I like to imagine, are ones Adawiya would have enjoyed. After all, it is through his music, whether online or on cassettes, in Egypt or at a distance from it, that the iconic artist will continue to endure in the ears, minds and hearts of so many.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.