There is an enormous gap between the late Edward Said’s public reputation and how he actually saw himself. It’s easy to understand why. His name is associated with several of the defining intellectual and political controversies of our era, including Palestine, Orientalism, postcolonial theory and identity politics. Said is remembered for myriad interventions, concerns and alliances: as a spokesperson for the Palestinian cause, a purveyor of “postmodernist” literary criticism, a lover of high-brow Western bourgeois and humanist culture, and a revolutionary activist and heir to Frantz Fanon.

Some of these roles were in tension with one another, and they have often been approached as separate personae or spheres of his life and work. But if there was a through-line connecting his multiple dimensions, if there was a consistent method in Said’s work, it was what he himself dubbed “secular criticism.”

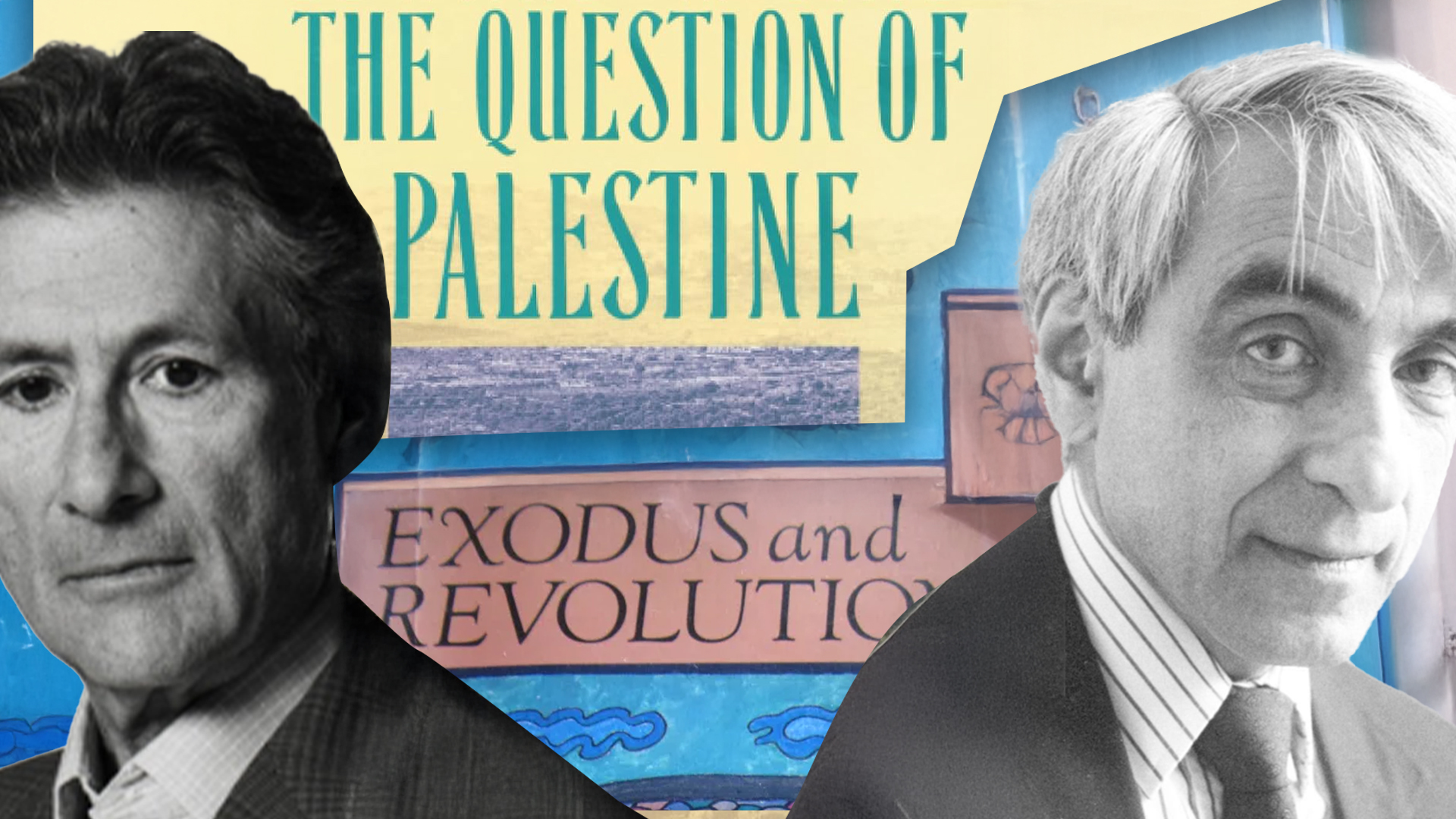

We can best understand what Said meant by “secular criticism” by revisiting his intellectual confrontation with the political philosopher Michael Walzer. Their critical engagement was sparked by Walzer’s book “Exodus and Revolution” (1985). There are two advantages to examining this particular controversy. One is that although it appears to concern something quite esoteric — the Old Testament — it turns out to be about so many other topics: Third World revolutions, the sociology of intellectuals, the fate of the left and interpretive methods among them.

But the dispute between the two influential intellectuals also spoke to an issue that remains urgently alive today. Walzer was among the foremost representatives of liberal Zionism, which is currently facing the most serious existential crisis in its history. Revisiting the Said-Walzer debate provides an occasion to consider the fate of liberal Zionism today by reappraising its arguments and their past incarnations. In retrospect, Walzer’s posture appears much less “liberal” (never mind “secular,” “universal” or “humanist”) than his reputation warrants, whereas Said appears much truer to his secular and internationalist commitments.

On Sept. 21, 2024, Walzer wrote an op-ed in The New York Times with the headline “Israel’s Pager Bombs Have No Place in a Just War,” criticizing Israel’s “exploding pagers” tactic against Hezbollah in Lebanon, which led to many civilian casualties. Halfway through the piece, Walzer clarifies: “However, let us make a distinction here. Condemning an act of war is not the same as condemning the war itself,” which is just in his opinion, since Israel’s enemies are driven by “an immoral and unjust purpose,” rendering Israel’s response — in Gaza and Lebanon — “justified.” Walzer is only concerned with the war’s conduct, and he insists that, with the exception of the pager attack, Israel’s response has been “limited” and “controlled.”

Walzer’s argument here contradicts the principles he himself set out in the seminal 1977 book “Just and Unjust Wars,” one of which was proportionality — it is entirely unclear how Israel’s response is proportional to the danger faced. But this exercise in philosophical hairsplitting speaks to a dilemma, perhaps even a crisis, within liberal Zionism. How can liberal commitments be maintained in a context in which the ethnic and religious nature of the Israeli state is becoming increasingly visible? It is striking how Walzer ascribes humane virtues to the Israeli state, as if its leaders shared his moral principles. What explains the asymmetry between liberal Zionism’s defense of moral universalism and its deep attachment to a particular ethnostate that consistently violates those very principles?

By the time Walzer’s book “Exodus and Revolution” came out in 1985, he had already established himself as the most important intellectual proponent of liberal Zionism in both academia and the American public sphere. Walzer, who was born in 1935, is a paradigmatic example of the generation of progressive intellectuals who were shaped by the movement against the Vietnam War but who later played a role in legitimizing American foreign policies such as the military intervention in Afghanistan. The outlook of this generation can be characterized as generally social democratic, in favor of what they deemed benevolent military interventions abroad and hostile to the legacies of anti-colonial and Third Worldist movements. There is a certain continuity between Walzer’s generation and an older generation of “Cold War liberals.” But there’s also discontinuity, owing to two facts: Firstly, Walzer’s generation identified with the “New Left” of the 1960s (especially over civil rights, feminism and the movement against the Vietnam War), and secondly, Israel and Zionism figured much more prominently for them than for earlier liberals.

“Just and Unjust Wars” cemented Walzer’s reputation as an authority on modern just war theory, but he had already made a splash as a political thinker through his writings on the Vietnam War, and later his strong defense of Israel following the 1967 Six-Day War. Walzer was a longtime editor and writer for Dissent, a magazine founded in 1954 as a platform for the democratic left that was critical of both Western capitalism and Soviet totalitarianism. Although critical of the Vietnam War, Walzer made clear in “Just and Unjust Wars” that he was neither a pacifist nor unequivocally anti-war. The book combined a modernized version of Catholic just war theory with wide-ranging historical illustrations from the Peloponnesian wars up to Vietnam and the Six-Day War. As Walzer himself acknowledges, the book was his attempt to clarify to himself why he was against the Vietnam War but a supporter of Israel’s 1967 offensive. Although the Six-Day War took up a mere five pages of the book (under the heading “Pre-Emptive Strikes”), it informed the project as a whole and motivated the question Walzer set out to answer. “Just and Unjust Wars” would go on to become a canonical text in military ethics, international law and political theory.

Relative to Walzer’s other major works of political philosophy, “Exodus and Revolution” is a fairly unremarkable book. It stands within a separate, and much less recognized, strand of Walzer’s intellectual oeuvre that began with his doctoral dissertation — published in 1965 as “The Revolution of the Saints: A Study in the Origins of Radical Politics” — and continued up to the four volumes he co-edited under the title “The Jewish Political Tradition.” These texts address the role of religious traditions in shaping history. “The Revolution of the Saints” is a sociological and historical study of the role of Calvinist and Puritan sects in creating the modern moral and political world, while “The Jewish Political Tradition” is a reconstruction and systemization of Talmudic political teaching. “Exodus and Revolution” is a reading of the interpretive tradition of the Book of Exodus, moving freely across the textual record from the traditional Jewish exegesis of the Midrash to “The Federalist Papers” and liberation theology.

Walzer was inspired to write the book during a visit to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1960, where he went to report on a sit-in led by Black students, which he called “the beginning of sixties radicalism.” He heard a sermon in a Baptist church that linked Exodus with the struggle of Black people in the American South. The connection struck him so much that he began to see Exodus and Moses everywhere he looked: The American revolutionaries, Oliver Cromwell, the abolitionists, liberation theologians and the preachers of the civil rights movement all alluded to Exodus. Walzer reached the conclusion that Exodus must be the paradigm of liberation that held the key to the entire revolutionary tradition.

Surely, as Walzer in fact acknowledges in passing, this claim flies in the face of the French revolutionaries and Marx, who did not deploy the Mosaic narrative. But Walzer is untroubled by this obstacle to his hypothesis. In a bizarre move, he catches a random quote in a text by a member of the Committee of Public Safety, the revolutionary body established in 1793 to defend the new French Republic from internal and external threats. The text said that the Terror must be endured for “thirty to fifty years.” Walzer extrapolated from this that the French must have been unconsciously invoking the Israelites’ “forty years” in the wilderness. This is his “evidence” for his underlying claim that even when the reference to Exodus is missing, it must be working unconsciously, so that it colors everything that can be said about “liberation” or “emancipation.”

But the book’s real political import appears in the final chapter, where Zionism is addressed directly. Walzer distinguishes between an “Exodus Zionism” and a “Messianic Zionism.” Exodus Zionism, according to this categorization, emphasizes the memory of the Israelites’ escape from Egypt, the 40-year journey in the wilderness and the arrival to the Promised Land. Messianic Zionism, on the other hand, emphasizes the future coming of the Messiah and the apocalyptic rupture that will mark this event. Exodus Zionism prioritizes the political agency of people shaping their own history, in that it tells a story of struggle against oppression and the drama of growing into political maturity following that oppression. Messianic Zionism, meanwhile, is less “tragic” in its sensibilities; it aims at a definitive rupture, not the slow, strenuous schooling of the desert. “Exodus Zionism” is moderate, reasonable, translatable, available to all revolutionaries and open to secular appropriation. “Messianic Zionism” belongs to the right-wingers from whom Walzer spent so much effort distancing himself. The goal of the book, then, was to offer a standpoint that allows liberal Zionism to compete with right-wing Zionism on the same religious and textual terrain.

But there are clear limits to this strategy, since the Exodus story is, in its own way, apocalyptic. There is a conquest of the land, as well as a divine commandment to slay its inhabitants. Walzer notes that “the Canaanites are explicitly excluded from the world of moral concern. According to the commandments of Deuteronomy, they are to be driven out or killed — all of them, men, women, and children — and their idols destroyed.” This is what by today’s standards we call genocide. But Walzer cites the Talmudic and medieval rabbis (including the 12th-century philosopher Moses Maimonides) who “rescinded” this commandment, since it “applied, the commentators argued, only to specific groups of people, named in the text, who no longer exist or can no longer be recognized.” This crucial matter concerning the relationship to strangers, or the inhabitants of the land, is dealt with in four pages out of 200.

This is why Said called his review of the book “A Canaanite Reading.” Although this point is not the only target of Said’s polemic, it shapes the entire confrontation. The book confirmed the argument of Said’s 1979 essay “Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims” that Zionism must depend on the fantasy that the land is uninhabited. And if “strangers” are found there, they are either “explicitly excluded from the world of moral concern” or they “no longer exist or can no longer be recognized,” in Walzer’s words. Walzer’s only concern was the right-wing Zionists who cite the commandment of killing all children and women to justify their actions, but he is not struck by the present-day question regarding the treatment of other inhabitants of the land. “The ban could have no practical effect; Jews returning to the land would not encounter Hittites and Amorites,” Walzer wrote, without naming who might be encountered.

The first half of Said’s review discusses the book itself, while the second half can be read as a “sociology of intellectuals” that places Walzer’s work in its social and historical context. Said opens the essay with an acknowledgment of Walzer’s erudition before proceeding to tear down his argument.

Said dubs Walzer’s tactic “inclusion by deferral,” meaning that Walzer keeps deferring possible limitations to his arguments as if they’re going to be addressed later, until they are forgotten, neutralizing their effect. “In fact,” Said writes, “a fog is exhaled by his prose to obscure those problems entailed by his arguments but casually deferred and avoided before they can make trouble. The great avoidance, significantly, is of history.” The result, according to Said, is a dressing up of deeply conservative ideas in progressive or radical garb.

Walzer had written in the book’s introduction: “I don’t mean to disparage the sacred, only to explore the secular: my subject is not what God has done but what men and women have done, first with the biblical text itself and then in the world, with the text in their hands.” However, as Said argues, Walzer cannot accomplish this feat of “exploring the secular,” since he gives up on any kind of historical rigor. Walzer believed he was secularizing the sacred, but he might as well have been sacralizing the secular.

“Given recent history,” Said wrote, “one would have thought that Walzer might have reconsidered the whole matter of divinely inspired politics and coaxed out of it some more sobering, perhaps even ironic, reflections than the one he presents.” Said didn’t pull his punches: “Why is Walzer so undialectical, so simplifying, so ahistorical and reductive?”

Said identified a significant ideological tension between Walzer’s characterization of Zionism as a national liberation movement and the fact that Western politicians and intellectuals had become increasingly skeptical of such movements globally. In the 1950s and 1960s, decolonization was a cause celebre among intellectuals and student movements across the world. Said asserts that by the 1970s and 1980s, the popularity of that cause had diminished among intellectuals and in general political discourse (with the notable exceptions of Nicaragua and South Africa). This decline corresponded to a significant shift across the political spectrum: An increasing preoccupation with “culture” and civilizational or religious discourses had eclipsed earlier terms, such as oppression and national liberation, as a way of understanding the colonial question. So how come Zionism is still defended in these terms, Said asked? Walzer himself is an example of this intellectual turn away from Marxism and toward identity politics (understood broadly to include religious and national identity). Even his more theoretical and systematic work — especially his 1983 book “Spheres of Justice” — was of a piece with this trend toward valorizing “community” as a framework for values, and thus expressed a version of cultural politics. So why did Walzer still need the notion of “revolution” when he himself was a decidedly postrevolutionary thinker?

Prior to 1967, when the alliance with the U.S. was still not decisive for Israel’s security, it was still possible for the Western left to support Israel on the grounds that it represented a new experiment in socialism. After 1967, this image of Israel became less palatable, due to military dominance, the increasing role of the occupation and the dependence on superpower (specifically American) support, a classical feature of settler colonialism. Meanwhile, the New Left was defined by its opposition to the Vietnam War and the Cold War. Support for Israel began to crumble due to these factors. It was this context that defined Walzer’s “mode of analysis,” as Said described it. Walzer’s goal was to convince his New Left generation that support for Israel did not entail a betrayal of their progressive commitments.

Said sought to illuminate a deeper issue in Walzer’s political philosophy, one that appears in other parts of his oeuvre as well. There was an asymmetry or tension in Walzer’s work between the claim to universality and his commitment to some kind of politics founded on identity or culture. In “Spheres of Justice,” Walzer criticizes liberal political theory for not paying sufficient attention to the plurality and incommensurability between different “social goods” and their corresponding modes of distribution (“spheres of justice”), implying that there can be no one single formula for equality since those goods can be valued in plural ways. One implication here is that communities have bounded and fixed ways of ranking their social goods that then define their standard of justice, and thus any attempt to criticize those communities must be “internal” — that is, constrained by the particular frame of justice in that community. The principles of justice are thus subordinated to local culture and identity.

This commitment to local context received its most developed articulation in Walzer’s book “Interpretation and Social Criticism” (1987). In that work, Walzer shifted between different forms of criticism. Political criticism (that is, criticism centered around the critique of state authority) was exhausted and gave way to cultural criticism (a critique of values), while the priority of ethnic, religious and national identity was simply assumed as the most relevant framing of the issue.

In this context, Walzer presented the idea of the “connected intellectual,” that is, one who maintains an emotional and moral sense of attachment to their community of origin. Walzer discussed multiple examples of “connected intellectuals,” but his hero was Albert Camus. Despite being an icon of anti-colonial sentiment within French intellectual circles, Camus criticized the excessive violence of Algeria’s anti-colonial resistance (the FLN) and sympathized with the French Algerian “pied-noir” community from which he came. Walzer argued that the critic must speak only to their people in order to appeal to their conscience and that the resources of identity, loyalty and intimate belonging have primacy over abstract moral prescriptions.

So Walzer wanted to have it both ways: He insisted on the centrality of criticism and reflection — and perhaps even a commitment to universal ideals — but this was constantly qualified by the requirements of community and belonging. This position allowed him to legitimize ethno-religious politics in a vocabulary that could be accepted by the left. It also explains his strategy with regard to Israel and Zionism. Effectively, the result is a closed moral universe in which the boundaries of the “community” are unquestionably accepted and ethno-religious forms of identity and authority are given priority. The effort to retain universal principles alongside particular forms of religious and ethnic belonging becomes increasingly strained. Walzer’s awkward borrowing of religious narratives in support of those universal principles is a symptom of this strain.

Here is what is at stake: How can the intellectual balance universal moral commitments and attachments to specific communities? Said posed two crucial questions: whether “critical distance and intimacy with one’s people” are mutually exclusive, and whether the critic who risks isolation from their community demands more respect than the “loyal member of the complicit majority.” The decisive term here is “risk.” Said holds that connectedness is not a sufficient measure for an act of criticism (although he accepts its importance) and that another crucial element is the degree to which the intellectual exposes themself to the risks of exclusion and reprisal from authority. This, he suggests, is the actual lesson of the “Western and Judaic traditions.” This seems to be the problem of “Exodus and Revolution”: None of Walzer’s arguments entail any exposure to risk, because nothing is actually staked. Both his “secular” (political) and “religious” commitments can be satisfied in the end, because he risked neither.

Said particularly criticized a statement that Walzer made in defense of the morality of “making them go,” that is, excluding certain people from a national community by making it easier for them to migrate. Walzer responded that this was just a realist acknowledgment of the politics of partition that are an inextricable consequence of national self-determination. But from Said’s point of view, this brought to light the way Israeli citizenship is specifically defended on ethno-religious grounds, thus making it impossible for Israel to be a “state for all its citizens.” This point seemed lost on Walzer, and one can only speculate as to why. His response was a typical “tu quoque” argument (or “whataboutery”): He claimed that he had remained entirely consistent throughout his life (as if this were a virtue) and instead took Said to task for his relationship with Yasser Arafat (Said was a personal adviser to and advocate for the PLO chairman, until the Oslo peace process of the 1990s). More insidious, however, was the following quote:

[Said] has made no effort to engage the religious fervor of contemporary Muslim Arabs, while Exodus and Revolution is at least an effort at engagement with the religious fervor of contemporary Jews. But maybe the only appropriate engagement is absolute opposition, a rejection not only of fundamentalism but of the entire religious tradition. As a member of the Palestinian Christian minority, face to face with an increasingly militant Islam, that is a natural, perhaps an unavoidable, course for Said — although I don’t know that he has ever urged it publicly upon his Muslim comrades in the PLO. But it isn’t a natural cause for me because of the way in which Judaism intersects with and partly determines the culture of the Jews.

Walzer here seemed to be suggesting that Said’s “minority” Christian status disqualified him from the same kind of “connectedness” to the Palestinian national movement that he (Walzer) enjoyed to Judaism and Israel. And now, having reduced politics and criticism to ethno-religious identity, he could evade the crux of Said’s criticisms regarding the particular method (or lack thereof) of such “engagement” with religion. He did not have to respond to questions of method because his identity exempted him from such questioning and Said’s political-religious identity disqualified him from raising such questions.

Revisiting the confrontation between Said and Walzer today illuminates the ways liberal Zionism both invests in, and disavows, its ethno-religious dimensions. By placing the Exodus story at the center of his account of “national liberation” and “revolution,” Walzer intended to secularize the lessons of the Mosaic account. But what happened instead was a reversal: “The secular” (in this case a particular nation-state, in history, called Israel) is sacralized; it comes to stand in for a sacred moral mission. In this context, it becomes increasingly impossible to maintain the balancing act of being both liberal and Zionist, especially as Israel becomes increasingly militarized and lawless.

Liberal Zionism (or socialist Zionism, for that matter) thinks it can control the consequences of its desires — for example, by distinguishing between a Messianic and an Exodus Zionism, and making the latter stand for a reasonable, universal politics. Eventually, however, the attempt to make fine distinctions between “good” and “bad” ethno-religious desires falls apart, since the ground on which those distinctions rests is ceded in advance to those willing to take the risks to realize their fantasies. Yet once those fantasies are realized, liberal intellectuals can always keep their good conscience intact, because they can project their desires onto others and then claim that they’re the victims of a tragic repetition of history. “Our intentions were good.”

But beyond the immediate political relevance of this episode, I also wanted to revisit the questions Said posed regarding method and criticism. It remains an open question how the assault on Gaza will impact the academic and intellectual worlds, and whether there is a chance here to undo the tyranny of culture wars, identity politics and debates over secularism. Said has often been read as a postmodern thinker who reduced truth to the empty play of power (although he refused and resisted the “postmodern” label). Said has also been criticized by some secular leftists for being insufficiently critical of Islamic movements and religious discourses (a criticism Walzer also raised in their debate). One writer-activist recently accused Said of “orientalism” because of his secular sensibilities.

All of those accounts fail to confront the specificity of Said’s mode of criticism. Said did more than offer a vocabulary for navigating these questions. He provided a concrete sociology of intellectuals that diagnosed the pathologies of intellectual and academic life. Said’s “secular criticism” is not without its flaws and ambiguities, but it can perhaps help those looking for a path beyond the intellectual dead ends that seem ubiquitous today.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.