It was a strange place to put a railway stop — at a nowhere site 60 miles west of Alexandria, with the blue Mediterranean on one side and the endless yellow-brown sand of the Egyptian desert on the other. The station was called El Alamein — “the two flags” in Arabic, named after how the engineers who built the rail line originally marked the spot. At first glance, it does seem to be an utterly random spot for a battle.

Yet, 80 years ago, on July 27, 1942, artillery, machine guns and tanks went silent on this front, stretching from El Alamein into the desert. The calm was temporary and the air tense. Two more battles would be fought here before the British 8th Army, under Bernard Montgomery, shattered the German and Italian forces commanded by Erwin Rommel and drove them out of Egypt in early November 1942.

Famously, Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the final triumph at El Alamein as the “end of the beginning” of World War II. In histories, it stands as one of the great turning points of the war. Both Montgomery and Rommel became mythic figures afterward, as if they were two gladiators alone on the field.

Today, a lifetime later, it is possible to see that the first battle at El Alamein was even more significant than the final one. That July in 1942 marked the end of the Axis advance in Africa — and the failure of Nazi Germany to conquer the Middle East.

More than that, by piecing together long-secret and long-lost evidence, we can see that a strange espionage affair led to both the battle itself and its outcome. Victory in the covert battle of minds preceded victory in the desert. Yet, with only one or two exceptions, the heroes of that struggle have remained anonymous, absent from history.

It all started when a radio message was sent from the Southern Command of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, to a top commander in Africa before dawn on April 24, 1942. According to a “particularly reliable source,” it said, “the British high command intends” to launch an offensive in Libya. The goal was to press westward beyond the port of Benghazi, which would provide the British with airfields close enough to Malta to give cover to convoys moving to the besieged Mediterranean island. As the British “operation is not possible before June,” the message said, “it will come too late.”

The radiogram was sent in the Enigma cipher, which was mathematically unbreakable, Germany’s military cryptologists were certain. A wireless operator at a British interception center listened to the dots and dashes of the Morse code and took down the scrambled letters. From there, the message went to Bletchley Park, an estate in the damp English countryside that had become the wartime home of Britain’s signals intelligence agency, GCHQ.

By 6 p.m., the codebreaking assembly line deciphered the message and passed it onto Hut 3, a squat brick-and-wood structure on the estate lawn, which handled army and air force intelligence. The duty officer marked it for urgent translation. Very few people would see the English version; breaking Enigma was Britain’s most desperately-guarded secret. The recipients included Gen. Claude Auchinleck, head of Britain’s Middle East Command in Cairo, and “C,” head of MI6, Britain’s foreign intelligence agency. Later that night, “C” delivered the text to Churchill. In the red ink that Churchill always used, he put a line next to the words “will come too late.”

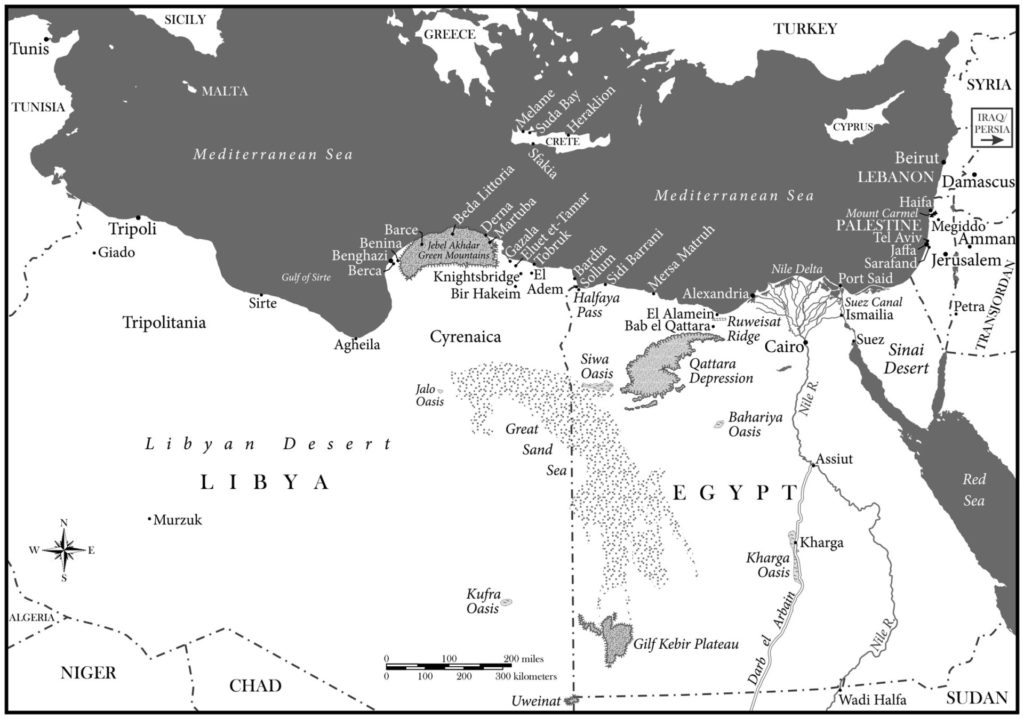

For a year and a half, the Eastern Mediterranean had been the main theater in which Britain fought Italy and Germany. Benito Mussolini, who was seeking a new Roman Empire, had ordered an invasion of Egypt from Libya, which was an Italian colony. The British army in Egypt counterattacked and drove the Italians back, halfway across Libya. So Adolf Hitler sent German divisions to Africa commanded by his favorite general, Rommel. The war seesawed across eastern Libya. Benghazi and other towns were conquered and reconquered four times and bombed by both sides.

Rommel would describe the campaign in Africa as “war without hate.” The British war correspondent Alan Moorehead wrote that it was “the most dangerous game on earth,” in which “no civilian populations were being destroyed.” This view seeped into later histories and was utterly Eurocentric, ignoring people who actually lived in Africa, their shattered cities, Italian brutality toward native Libyans and the concentration camp where eastern Libyan Jews were sent on Mussolini’s orders.

In April 1942, the two armies faced each other on a front in the Libyan desert, west of British-held Tobruk, a strategic port town. Strictly speaking, the 8th Army was “Allied” rather than “British” per se — it included Indians, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Free French and others. Churchill wanted Auchinleck to attack quickly but the general had already written that “he would not have reasonable numerical superiority until June 1.” The decrypted Enigma message confirmed Churchill’s fear that this would be “too late” and that Rommel, always the daring gambler, would strike first.

Focused on this fear, the usually sharp-eyed prime minister failed to ask how the “particularly reliable source” knew the plans of the British command in Cairo. At Bletchley Park, the person assigned to ask such questions was a 24-year-old woman named Margaret Storey.

Bletchley Park’s codebreakers had been cracking Enigma on German air force networks for two years. (Contrary to popular perception, reinforced by the 2014 film “The Imitation Game,” the British mathematician Alan Turing did not solve the Enigma puzzle. That honor belongs to the nearly-forgotten Polish mathematician Marian Rejewski. However, with the help of Gordon Welchman, a Cambridge University colleague, Turing did design the machine that made daily cracking of Enigma possible.) In the spring of 1942, the British code wizards finally began breaking into the networks used by the German army in North Africa. On April 29, they succeeded in cracking a five-day-old army message. This one cited a “good source” and was more specific: The British offensive would not begin before June 1.

By this time, their own success at breaking Axis ciphers was shaping the nightmares of Bletchley Park’s commanders, in which Germans and Italians were cracking British codes. Someone had to look through Axis messages for signs of intelligence success against Britain.

Storey, who was chosen as the analyst, had started at Bletchley Park at the lowest rank, as an untrained clerk. Official records say almost nothing else about her. People who knew her later, whom I was able to track down, described her as a slight woman — “shy, very shy” — who dressed in browns, smoked incessantly, remembered every word she read and heard, identified flowers by their Latin names, spoke nine languages and showed “absolutely formidable intelligence.” The messages intercepted about British plans for June reached her desk immediately or soon after they were deciphered.

More suspect messages followed. On May 2, two were addressed to Rommel’s headquarters, each quoting “a good source” and reporting a different British division in the Middle East that was not fit for combat. Soon after, Rommel received another Enigma radiogram packed with “good source” reports. It included map coordinates of British units in Libya, information about minefields and an assessment of Italian and German forces that was apparently drawn from a British intelligence document.

The better that Bletchley Park’s codebreakers became at cracking the German army’s Enigma messages, the more evidence appeared that Berlin was receiving high-value information from inside British headquarters in Cairo.

Before the sun rose on May 27, Rommel led his armored forces as they looped around the end of the British minefields and fortifications and struck from behind. He had used this classic maneuver in North Africa because, no matter how long a defensive line was, it always ended in open desert. Just as the source in Cairo had indicated, he had struck before June.

In Luftwaffe messages, the source was often “particularly reliable.” One radiogram reported that Britain’s Royal Air Force technicians were failing at maintaining American-made warplanes. The source reported how many tanks the British had left and the precise territory held by the Free French forces at Bir Hacheim, the desert redoubt that blocked Rommel’s advance toward Tobruk. The British still seemed “to believe firmly” that the Axis forces would withdraw, one message said.

In her reports, Storey assessed that the source was a German agent, although this wasn’t certain. But the clues pointed to a well-placed person, privy to British commanders’ discussions, who had gone over to the enemy.

On June 10, the Free French were preparing to pull out of Bir Hacheim under intense German pressure. At Bletchley Park, a long “good source” message was deciphered. It said that, a month earlier, the source had visited British units preparing for battle. “Training inferior according to American ideas,” the source reported.

This changed the assessment. Logically, only an American would make this comparison — an American with access to British training exercises. Either an American turncoat in Cairo was passing U.S. reports to German intelligence or the Germans could read a code in use between Cairo and Washington.

Bletchley Park had a top-secret channel to the U.S. War Department’s Signal Intelligence Service (SIS), the agency that created U.S. Army codes and cracked enemy ones. Messages sent on this channel were recorded in a logbook that would remain classified for over 60 years. Beginning June 10, 1942, the log shows an urgent conversation between Bletchley Park and the War Department, conducted in slow motion because of time zone differences and the need to investigate quietly at each end.

A British colonel warned that a U.S. code had likely been broken. William Friedman, the SIS chief, asked which one. The British couldn’t possibly know; they were breaking German codes, not American ones. The colonel described the purloined message about U.S. warplanes. That, Friedman answered, had been sent in the Military Intelligence Code, used by the U.S. military attache’s office in Cairo. But the code had since been replaced, Friedman said, so the leak was probably due to “enemy agents.”

The director of Bletchley Park, Edward Travis, lost patience and stepped in. He sent the text of a new “good source” message that “reveals our future plans.” The German radiogram said that British commandos would simultaneously attack nine German airfields on the night of June 12. By the time the codebreakers had deciphered that message, it was too late to alert the commandos that the Germans were expecting them. The raids failed. At one German airfield in Libya, an entire commando squad was killed or captured.

The Bletchley Park logbook does not tell what happened next in Washington. But quiet inquiries would have shown that the message about commando raids was virtually a direct translation of a radiogram from Col. Bonner Fellers, the U.S. military attache in Cairo — and that he was still using the Military Intelligence Code.

Fellers was a 46-year-old career officer. The U.S. Army had sent him to Cairo after Italy invaded Egypt. Since then, he had been the American best placed to report on fighting with German and Italian forces. By June 1942, his office had grown to two dozen officers and civilians because the War Department in Washington was ravenous for information.

In private letters, Fellers was self-deprecating. In his radio reports — some preserved in scattered archives, some in manila envelopes left in a Washington, D.C., attic — his tone was omniscient. He reported on Axis and British tactics, on the performance of American-made tanks on the Libyan front and often on British mistakes. In the spring of 1942, British officers in Egypt received an order restricting what they could tell Fellers. Revealing dates of planned operations was explicitly forbidden. The order had little or no effect. Men seemed to have an irresistible urge to talk to Fellers.

In Washington, the War Department’s cryptologists were either slow to identify the suspect code or hesitant to inform their British allies. A cable from “C,” threatening that Churchill would personally wire President Franklin D. Roosevelt, finally brought an answer. Washington had confirmed that “the cypher of the American Military Attaché in Cairo is compromised,” as “C” told Churchill on June 16, writing that he had asked the Americans to switch immediately to a more secure code. If they did, and the leak continued, “we shall then know for certain that there is a traitor in Cairo.”

Churchill flew to Washington to discuss strategy with Roosevelt. The two leaders were sitting in the Oval Office with their top generals on June 21 when an aide brought in a radiogram from Fellers in Cairo, from the night before. It said, “Rommel took Tobruk.” The news was “a staggering blow,” a British general wrote. Tobruk stood for British resilience. The year before, it had withstood a nine-month siege. Now it fell in a one-day battle.

Fellers followed up with a long message dissecting British failures. The 8th Army, he expected, would retreat eastward to the harbor of Mersa Matruh, halfway across Egypt, to mount its defense of that country. He was not optimistic. “If Rommel intends to take the [Nile] Delta,” Fellers concluded, “now is an opportune time.” Taking the Delta meant taking Alexandria and Cairo. It meant conquering Egypt.

Roosevelt read that cable. Rommel read the gist of it, including the conclusion, perhaps before Roosevelt did. Storey read it at Bletchley Park with its attribution to a “good source.” Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law, wrote in his diary that from “cables from the American observer at Cairo, Fellers, we learn that the English have been beaten” and that if Rommel kept going, he could reach the Suez Canal.

Rommel’s orders had been to stop at the Egyptian border. The next operation on the Axis agenda was invading Malta, in the strategic straits between Tunisia and Sicily. His troops were exhausted, his supply lines stretched. He had only 44 tanks left. Yet the intelligence source that had guided him so far said Egypt was his to take. He was a gambler — but one who knew the other side’s cards.

Officially under Italian command, he appealed to Mussolini, who consulted Hitler. “The goddess of history only approaches a leader once,” Hitler answered. Rommel would conquer the Middle East, the Nazi dictator said, while German forces advancing in Russia would sweep down through the Caucasus region in a pincer movement and bring “the collapse of the entire eastern part of the British Empire.” Rommel, the gambler, put all his chips on one bet and plunged his army into Egypt in pursuit of the retreating British. It was June 23, 1942. On June 24 or early on June 25, the “good source” went silent.

Here’s one piece of evidence: On June 23, Roosevelt and Gen. George Marshall were leaning toward sending a U.S. armored division to Egypt to reinforce the British. Late on July 25, the proposal was dropped as impractical. Ugo Cavallero, Italy’s army chief of staff, knew of the intent to send the division — but not that it had been called off. The plan, that is, was sent to the U.S. military office in Cairo in the old code. The cancellation was encrypted in the replacement cipher, which stymied Axis codebreakers.

The War Department had promised to change the code a week earlier, before Tobruk fell. A U.S. intelligence officer who visited Bletchley Park a year later explained that the War Department wrote Fellers a radiogram ordering him to change the code on June 17. After encryption, radiograms were sent commercially, via the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). “For some incomprehensible reason,” the U.S. officer explained, “RCA failed to send the message.” Somehow, it seems, the radiogram form was misplaced — and a week passed. Instead of a traitor, there was carelessness.

The timing of the actual change of codes was exquisite. On the afternoon of June 25, Auchinleck made two decisions. The first was to fly to the battle headquarters at Mersa Matruh and dismiss the commander of the 8th Army, Neil Ritchie. In his place, Auchinleck himself took command in the field.

Auchinleck’s second decision was to move the main defensive line further back, closer to the Delta. A residual force would stay at Mersa Matruh to slow the Axis army. Most of the 8th Army retreated over a hundred miles more, to a line that started at El Alamein. That was the point where the coastline was closest to the Qattara Depression, a vast impassable lowland surrounded by cliffs. The new defenses stretched from the coast to the cliffs. This time, Rommel would not be able to go around the British line.

The Axis army pushed through Mersa Matruh on June 29. The next day, the army’s chief medical officer radioed warnings to units that, when they reached Egyptian cities, they should avoid drinking unboiled water or buying ice cream from street vendors. This was just one of the Enigma messages decoded in Bletchley Park, showing the certainty of Rommel and his staff that they would soon be on the streets of Cairo and Alexandria. The German commanders knew there was a British “strongpoint” at El Alamein but expected to “mop up” quickly and keep going. A message saying this was deciphered at Bletchley Park.

The codebreaking assembly line churned ever more intelligence for Auchinleck, including details of Rommel’s battle plans. At the same time, Rommel lost his dependable source. He was driving at top speed while blind.

Rather than a surprise attack, Auchinleck mounted a surprise defense. When the Axis forces reached El Alamein on July 1, two German armored divisions were assigned to speed between British positions and attack from behind. They found themselves blocked by an Indian brigade. A German infantry advance smashed into a South African division whose existence was unknown to Rommel.

By the third night, Rommel told the German high command that the British strength and his own forces’ “most precarious supply situation” forced him to pause the attack. The battle continued; Auchinleck’s bids to push back the Axis stalled — but Rommel failed to break through. Deciphered Enigma messages revealed that German armored forces were desperately short of fuel and ammunition. Logistics had always been the weakness in Rommel’s plans. His gamble in invading Egypt was that he would quickly conquer the port of Alexandria, where Italian ships could bring supplies.

On July 27, when the exhausted armies stopped fighting, it had been exactly two months since Rommel launched his offensive. On the map, the German and Italian forces had advanced 400 miles and were a day’s march from Alexandria. “Auchinleck had lost and Rommel had won,” albeit “for complicated reasons far beyond the control of the two men,” wrote the war correspondent Moorehead. At that moment, it was natural to fear the next Axis advance — to the Nile and far beyond. Egypt’s Prime Minister Mustafa al-Nahhas asked the British ambassador Miles Lampson for a promise that, “if there was fighting in the Delta,” British forces would not destroy oil wells and refineries. Among Jews in Palestine, one writer recorded, “the rumor spreads … that the British are about to pull out of Palestine” as well as Syria and Lebanon. Churchill flew to Cairo, dismissed Auchinleck and put Montgomery in command in the desert. Three months later, Montgomery launched the counteroffensive that shattered Rommel’s army and set off the long Axis retreat.

In reality, though, Rommel had already lost his gamble — and with it the battle for Egypt — by the end of July 1942. He had not reached Alexandria. His army was stranded in the desert. Tobruk’s port could handle only a fifth of the supplies that the Italians and Germans at El Alamein needed. The rest had to come by truck convoys traveling 800 miles from Benghazi or 1,400 miles from Tripoli. Deciphered Enigma messages regularly reported the Axis shortage of fuel and food.

The rational military decision would have been to retreat, but Rommel did not serve a rational master. At the end of August, he tried again to break through the British line, ran out of fuel and failed. Montgomery’s victory in November was the sequel of Auchinleck’s unrecognized victory in July.

Yet the names of the generals, as the war correspondent Moorehead correctly pointed out, are shorthand for more complex factors. One of those was espionage. Another was chance.

In June 1944, Allied forces conquered Rome. MI6 agents, who arrived soon after, found and questioned four former members of an Italian counterintelligence unit known as the Sezione Prelevamento, or the Removal Section. In the process, they solved the mystery of the “good source.”

The Removal Section removed secrets from foreign embassies. In the fall of 1941, just before the United States entered the war, section commander Manfredi Talamo, or one of his men, entered the U.S. embassy in Rome during off hours and unlocked the safe of the military attaché. He removed the codebook for the Military Intelligence Code, took it to a nearby photo studio, photographed the pages and then returned the book precisely to its spot. Within weeks, Italy’s signal intelligence agency was intercepting messages from Cairo. By January 1942, the Italians had shared the code with their German counterparts.

It was a remarkable intelligence feat. It was undone by the greater feat of breaking Enigma. To use the shorthand of people’s names: In the covert battle, Rejewski, Turing, Welchman and Storey defeated Talamo.

As for the role of chance: If the radio message telling Fellers to change his code had been sent on time, Rommel might not have rushed toward El Alamein. If the message hadn’t been found and sent a week later, Rommel would still have had his source and the battle could have gone differently. If that had happened, there is no knowing what course the war would have taken — or what the Middle East would look like today. Indeed, if that had happened, there is no knowing to which victors history would belong.