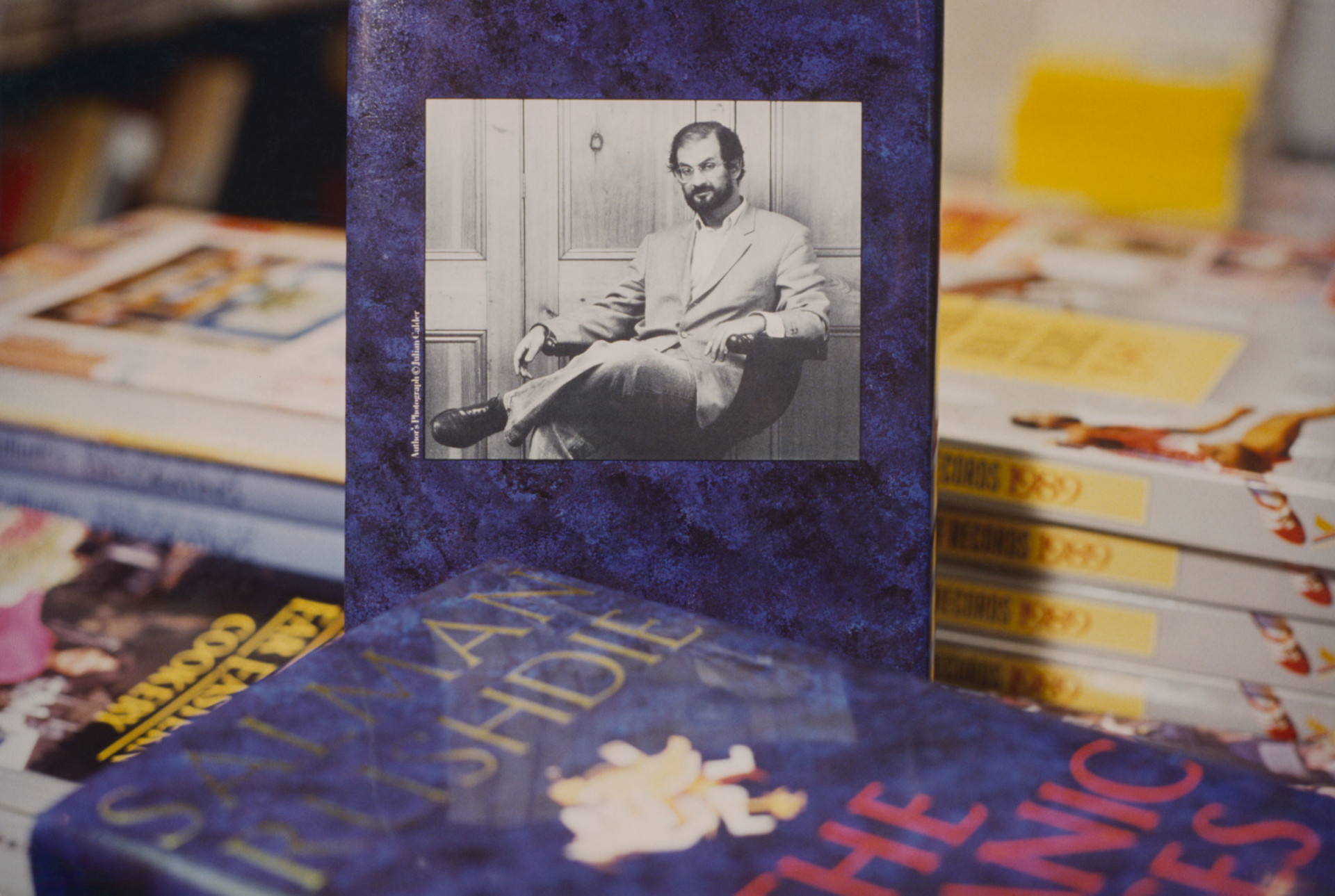

When it comes to revenge, there is no statute of limitations. This is what Salman Rushdie discovered last week. After evading injustice for so many years, the acclaimed-despised, celebrated-hated, subversive-subverted British-Kashmiri author had finally let down his guard, only for the long arm of the lawless to catch up with him. Decades after the release of “The Satanic Verses,” Rushdie remains one of the most wildly and widely misunderstood contemporary writers in the English language.

As a lover of literature and an advocate of freedom of expression, I decided to reread the book that spawned the fatwa, both as an act of solidarity with an artist whose life was almost cut short and to clear up the myriad misconceptions surrounding Rushdie and his novel. As a committed believer in and defender of free speech and freedom of conscience, I see no problem with Rushdie or any other person insulting or even mocking a religion or philosophy. No system of beliefs is so sacred that it is beyond criticism or ridicule.

Hadi Matar, the California-born 24-year-old who leapt on stage and repeatedly stabbed the writer, disagreed. The Lebanese-American who has expressed sympathies with the Iranian regime and admiration for the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as well as contempt for Rushdie appears to have been so angered by the author’s fourth novel, which was published in 1988, that he decided to carry out the death sentence against Rushdie proclaimed in the now-infamous fatwa that Khomeini issued the following year.

That fatwa galvanized what had been isolated local protests into international fury. In so doing, Rushdie metamorphosed, like a character in one of his novels, from a writer and a role model for British Muslims into a supervillain for conservative and radical Muslims around the world.

And all because the book allegedly insulted Muhammad and Islam, an excuse that has been repeatedly used by extremists to justify murder, such as the slaughter committed at the offices of the controversial satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015. However, “The Satanic Verses” is not some cheap shot or diatribe against Islam, as its haters allege.

This is not as surprising as it now sounds. Although “Satanic Verses” touches on Islamic themes, the novel is not primarily about the religion. “Let’s remember that the book isn’t actually about Islam, but about migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death, London and Bombay,” Rushdie insisted in a 1988 letter to then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who had decided to ban the importation of the novel.

“It’s a novel which happens to contain a castigation of Western materialism. The tone is comic,” he reiterated in an interview he gave to British journalist and author Hunter Davies in 1993. “All the attacks are by people who have not read the book. If anyone reads the book, they will see what I was trying to say.”

Surely not, you might think. Surely, nobody would burn a book before reading it or wish death on its author without having weighed up all the evidence first. But, in most cases, that is, sadly, precisely what happened.

This is confirmed in later admissions by some protesters and by the fact that many of the protests took place in countries where the novel was banned or unavailable. Even Khomeini had not read the book before issuing his death sentence, his son told an American reporter in the early 1990s. As for Hadi Matar, Rushdie’s attacker admits to having read only a couple of pages of the book.

So why did the Iranian Supreme Leader issue his life-destroying fatwa?

Not for any theological reasons but for purely political expediency following the incessant political lobbying of two fanatical British Muslims. With a swish of his pen, Khomeini gained significant political capital in the long-standing cultural war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, diplomatic relations between which had worsened significantly since the Islamic revolution in Iran a decade earlier. It also helped the ayatollah to shore up support and silence dissent following the disastrous and costly war with neighboring Iraq, which had ended in September 1988, the month Rushdie’s novel was published. And it aided him in deflecting concerns about his unstable mental state, which manifested itself in another, less-famous but deadlier Khomeini fatwa, issued in the summer of before the release of “The Satanic Verses,” that led to the execution by “death committees” of 30,000 political prisoners in Iran, mostly leftists and communists.

There was also a potential personal motive informing Khomeini’s decision: the short section of the novel pillorying a Khomeini-like character, referred to as “the imam,” who, like the ayatollah, was exiled from his homeland.

Before Khomeini’s fatwa, Rushdie had actually been a popular figure in Iran for his unflinching criticism of the hated shah as well as for his opposition to and criticism of Europe’s colonial legacy and U.S. militarism and foreign policy, including a book he published condemning U.S. involvement in Nicaragua. An unofficial Persian translation of Rushdie’s novel “Shame,” which was a stinging allegory of post-Partition Pakistan, won a prize in Iran, and, surprisingly, “The Satanic Verses” was also available in Persian prior to the fatwa.

Hard as it is to imagine today, back on his home turf, in India and in the U.K., Rushdie was once respected by those who had read his books or heard about them for exploring issues relating to post-colonial identity and politics, racism and alienation, migration and immigration, as well as East and West. His sublime “Midnight’s Children,” which is a tour de force of contemporary literature and his best novel, should be the legacy he is most remembered for, rather than the manufactured controversy about “The Satanic Verses.”

Rushdie’s mercurial ability at the time to appeal to Eastern and Western audiences simultaneously (before he felt pushed by fanatics out to kill him or wishing him death to pick a side) and the fact that he wrote “The Satanic Verses” primarily for people like him, caught between two worlds, led the controversy and death threats to completely blindside him and to hurt intensely. “I knew the mullahs would not like it, but I don’t write to please the mullahs,” Rushdie told Hunter Davies. “It is the job of an artist to be iconoclastic, to give the dissenting view. Cultures can’t stand still. I expected a few mullahs would be offended, call me names, and then I could defend myself in public. I was prepared for that.”

Having pored over the novel again since last week’s attack to refresh my memory, I am struck that one of the most ridiculous allegations leveled against the book is that it is an Islamophobic diatribe and that it was written to pander to Western bigots and play up to Western stereotypes of Islam. The Iranian regime went so far as to depict the book as a British conspiracy against Islam. Some non-Muslims also accused Rushdie of treachery. The British conservative politician Norman Tebbit alleged that Rushdie possessed “a record of despicable acts of betrayal of his upbringing, religion, adopted home and nationality,” taking a jab, in the process, at Rushdie’s biting criticism of British imperialism and the British raj in India.

However, nothing could be further from the truth, and an Islamophobe would find little comfort in the pages of the novel. In fact, the reason many Islamophobes and anti-Muslims became defenders of Salman Rushdie was not because of what he wrote in the novel but because of the violent reaction of Khomeini and radical Muslims.

Despite its irreverence and its surrealist comic humor, Rushdie’s novel expresses compassion and admiration for the Prophet Muhammad, in fictional dream sequences that take place in the feverish imaginings of the novel’s main protagonist, Gibreel Farishta, a fictional Bollywood superstar who crash-lands, unscathed, in England after the hijacked plane he is on explodes in mid-air.

Although when viewed through an orthodox religious lens, the fictional-factual “Mahound,” as the prophetic figure is called in the novel, appears sacrilegious and even blasphemous, he is fleshed out humanely and sympathetically.

Even Mahound, a name historically used by Western anti-Islamic polemicists to refer to the Prophet, is employed ironically. “[He] has adopted, instead, the demon-tag the farangis hung around his neck,” Rushdie writes in the novel. “To turn insults into strengths, Whigs, Tories, Blacks all chose to wear with pride the names they were given in scorn.” (Tories, a term that was once used to refer to robbers and papist outlaws, and Whigs, which once referred to cattle drivers, began life as derogatory terms for two English political factions but were later normalized.)

Rushdie writes admiringly of the Prophet’s rise from rags to riches, despite being an orphan, his modest and ascetic lifestyle, his devotion amid adversity, his courage in the face of persecution and his largely magnanimous attitude toward victory upon his triumphant return to the fictionalized Mecca (called “Jahilia” in the book).

In a context where most contemporary Muslims reject even the depiction of their prophet, Salman Rushdie’s great sin was to portray his fictionalized Muhammad as an imperfect and fallible human being, complete with weaknesses and foibles. This has become an almost unforgivable transgression for mainstream Islam, even though the Prophet himself never tired of emphasizing he was a mere mortal man, in part to contrast himself with the divinity attributed to his predecessor, Jesus.

This point was reiterated on the lips of Hamza, Muhammad’s paternal uncle, in the novel: “Oh, Bilal, how many times must he tell you? Keep your faith for God. The Messenger is only a man.”

How did Muhammad rise from self-described imperfection to become an immaculate and pretty much flawless human?

Part of the reason is how Islam evolved to base a large portion of its religious laws and practices on the Hadith, i.e., the reported utterances and actions of Muhammad. If the Prophet does not err, then any hadith considered to be authentic and reliable can be used to underpin religious laws and fatwas. If, in contrast, the Prophet is imperfect, then the foundation of Islamic law could crumble and Islamic scholars are faced with the additional dilemma of filtering out when Muhammad was acting like a human and when he was behaving like a divine conduit.

Some Muslims see Salman Rushdie’s decision to wade into the historical controversy surrounding the Satanic Verses, which is a term used by Western Orientalists and not by Muslims, as a sign of hostility and ill intent. Known as the Gharaniq (which appears to mean crane or water bird) Verses to Muslims, these relate to an episode in which Muhammad, desperate to convert Meccans to Islam, supposedly receives a revelation that the most important goddesses of the Arabian pantheon — al-Lat, al-Uzza and Manat — are “exalted” and their “intercession is hoped for,” a message that chimed with pagan ideology but contradicted Islam’s doctrine of absolute monotheism and its absence of intermediaries. Later, the Angel Gabriel informed him that the verses were false and God revoked them.

Many of Rushdie’s critics go so far as to claim that this incident never occurred and is a later fabrication. However, for the first two centuries of Islam, the authenticity of the verses was accepted by early biographers of Muhammad and Islamic scholars. This began to change as the Hadith took on a central role in Islamic jurisprudence.

Rather than a manifestation of anti-Islamic orientalism, I see Rushdie’s exploration of the Gharaniq or Satanic Verses as the soul searching and questioning of a troubled believer on the brink of losing his faith. This is reflected in some of the other suspicious or troubling incidents referred to in the novel in which the Angel Gabriel delivers, right in the nick of time, divine revelations to Muhammad that directly serve his personal interests, rather than those of the community or humanity at large.

These include revelations, which have also troubled Muslim skeptics and atheists I have spoken to and interviewed, allowing the Prophet to marry as many women and keep as many concubines as he wished (Surat al-Ahzab 50-52) or exonerating his young wife, Aisha, of rumors that she had committed adultery. Rushdie’s way of dealing with these inconsistencies and contradictions is to imagine in the novel that Muhammad truly believed he was hearing the archangel Gabriel but that the two were effectively one, with the angel telling the Prophet essentially what he wanted to hear.

In my reading, Rushdie alludes to his own personal doubts through a namesake character in the book, Salman the Persian. Although there was a companion of the Prophet named Salman al-Farisi from Persia, his real biography is quite different to the one presented in the novel. The real Salman was not only considered by Muhammad to be a member of his household, he remained a faithful Muslim after the Prophet’s death, participated in the conquest of the Sassanid empire and became a governor in al-Mada’in in Iraq.

In Rushdie’s version of Salman, the Persian loses his faith in the Prophet and flees to Mecca just before Muhammad’s triumphant return, after which he makes his way back to his homeland. Apparently borrowing elements from the story of one of Muhammad’s scribes Abdullah ibn Saad, Salman the Persian begins to have his faith shaken when he makes changes to some of the revelations Muhammad recites and the Prophet does not notice. Likewise, the fictional Salman the Persian’s creator, Salman the Writer, makes changes and adaptations to the story of the Prophet’s life in his fantastical novel.

“After that Salman began to notice how useful and well timed the angel’s revelations tended to be, so that when the faithful were disputing Mahound’s views on any subject… the angel would turn up with an answer, and he always supported Mahound,” Rushdie writes in the novel, a suggestion that would strike a believing Muslim as offensive, even heretical, as Gabriel is believed to be the instrument of God, not a tool of the Prophet.

The detailed theological explorations and the crises of faith expressed in the text and subtext underscore an important dimension usually missing from the debate on Salman Rushdie and “The Satanic Verses.” Both critics and admirers tend to see Rushdie and his fourth novel as a primarily western phenomenon, an anomaly, an exception, un-representative of his background and culture. This is reflected in both the widespread perception among Muslims that Rushdie was a sell-out and western stooge and the common view in the West that Khomeini and the book-burning protesters were the more authentic representations of Islam. However, not only did it take months of incitement by fanatics before some semblance of outrage broke out, far more Muslim countries did not see protests than those that did. I had just moved from England to Egypt at the time, and I recall little to no interest in the affair.

Sadly, some natural allies of Rushdie turned shamefully on him. One example was Egyptian Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz, who bitterly criticized Rushdie, even though he himself had been pursued by extremists for his own allegorical novel Awlad Haretna, first published in 1959, which led to his being stabbed in the neck in 1994, like Rushdie later would be.

However, quite a few courageous intellectuals in Arab and Islamic countries stuck their necks out, even if a blade may have hovered nearby, to defend Rushdie, risking the fury of extremists. “Perhaps the deep-seated and silent assumption in the West remains that Muslims are simply not worthy of serious dissidents, do not deserve them, and are ultimately incapable of producing them; for, in the last analysis, it is the theocracy of the Ayatollahs that becomes them,” wrote the late Sadiq Jalal al-Azm, the prominent and outspoken Lebanon-based Syrian writer and intellectual who knew a thing or two about dissent.

For example, al-Azm’s Critique of Religious Thought caused such an uproar when it was published in 1969 that it led to his imprisonment in 1970 for supposedly inciting sectarianism in Lebanon, and to the banning of the book in most of the Arab world. “Rushdie’s fiction is an angry and rebellious exploration of very specific inhuman conditions and very concrete wicked social situations and rotten political circumstances,” al-Azm insisted.

The prominent Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, famed for his critiques of western orientalism but less well-known for his equally scathing deconstruction of Islamic and Arab societies, was also a great defender and admirer of Rushdie’s oeuvre of dissent (in fact, the two men, both of whom shared a sense of disjointedly floating between worlds and cultures, had been mutual admirers in the 1980s). “Rushdie is everyone who speaks out against power, to say that we are entitled to think and express forbidden thoughts, to argue for democracy and freedom of opinion,” Said wrote in the early 1990s. “His case is not really about offense to Islam, but a spur to go on struggling for democracy that has been denied us, and the courage not to stop. Rushdie is the intifada of the imagination.”

Rushdie himself located his controversial novel within the Islamic, rather than western, tradition. “The Satanic Verses,” he explained at the time of the fatwa, was “about a dispute between different ideas of the text. Between the sacred and the profane ideas of what a book is” and that this debate “existed within the life of the Prophet Muhammad, between himself and other kinds of writers, which I didn’t make up.”

“It’s rather strange that a book which discusses that dispute immediately becomes surrounded by exactly that dispute,” he observed wryly.

Long before Rushdie penned “The Satanic Verses,” equally and even more irreverent and sacrilegious works of literature were published in Arabic. For instance, the Iraqi poet, reformer and atheist Jamil Sidqi al-Zahawi (1863-1936) published, in 1931, “Revolution in Hell.” In this epic poem, humanity’s most daring and original thinkers have been condemned to eternal damnation as punishment for their courage, while the obedient and pro-establishment are rewarded with everlasting paradise, in a clear allegory of how Arab patriarchal dictatorships operate. The subversive inhabitants of hell storm heaven and claim it as their rightful abode.

Like Rushdie, al-Zahawi was also building on an existing literary tradition. “Revolution in Hell” was, in fact, inspired by a significant medieval work of skepticism, “The Epistle of Forgiveness,” which was written by Abu al-Ala’ al-Ma’arri (973-1057), the blind Syrian poet, philosopher, rationalist and hermit who was both a vegan and believed that humans should stop reproducing. Taking the form of a letter to a self-righteous sheikh and traditionalist who had attempted to initiate a correspondence with al-Ma’arri, the rebellious poet sends his hypocritical correspondent on a fantastical trip to paradise and hell. This fictional journey to the afterlife was irreverent, skeptical, satirical and deeply ironic. It ridiculed the Quranic and Islamic conceptions of heaven as a sensual abode for the pious by placing heretical and pagan poets and men of letters, including those that the sheikh had condemned as unbelievers, in paradise. The “Epistle of Forgiveness” also transformed entry into heaven into a bureaucratic process tied up in red tape, with a gatekeeper who explains to the sheikh, who has lost his certificate of repentance, that “for humans I cannot intercede.”

What all this reveals is that there was nothing inevitable about the reaction to “The Satanic Verses,” as some seem to believe in hindsight. Had Khomeini not issued his fatwa, vengeance could have found another path to the novelist or Rushdie may well have continued down the path of being a progressive and leftist author living an open, fulfilling and safe public life, adored by the marginalized and disenfranchised minorities of Britain and other countries and reviled by the self-declared anti-PC, anti-woke crowd that now claim to love him.

It is my sense that, in the decades since the Rushdie affair blew up, the ranks of Muslims wishing to silence the irreligious have dwindled, while the ranks of those of Muslim origin who are openly secularist, anti-religious or even atheist are swelling, as pushback against the fanatics that have tried to hijack our societies and as the wave of Islamism that began in the 1970s recedes. And there is relative safety in numbers, at least for those of us who live in societies that do not criminalize unbelief.

As an atheist, I have so far been able to write and speak with complete freedom without suffering any serious threats to my safety or person, beyond infantile insults and threats on social media. However, I am aware that it is a roulette wheel, and misfortune, though improbable, can strike at any time. But at least here in Europe, it is only the risk of vigilantism that I must be wakeful to, and not persecution by the state, as occurs to free thinkers in places like Saudi Arabia and Iran.

In the course of my writing adventure, though I lack Rushdie’s sublime talent as a storyteller, I have been fortunate enough to draw Muslim readers, especially in the West and the more secular Arab and Muslim countries, who increasingly tend to be like how Rushdie expected them to be when he wrote “The Satanic Verses”: able to distinguish literature and art from theology, willing to be challenged, able to cope with criticism of the things they hold sacred and capable of defending their convictions peacefully, with words rather than swords. While the danger of fanaticism flaring up is always near and present, especially in times of socioeconomic and political crisis, I truly hope that the pendulum continues to swing toward the peaceful and tolerant.