On Jan. 21, 2023, a lawsuit filed by Erika López Prater against Hamline University, which dismissed her from teaching because she showed her class historical Islamic paintings of the Prophet Muhammad, became publicly available. That same day, I was attending an international workshop on Islamic piety in Turkey. As news of the lawsuit made the rounds, I listened to several of my colleagues present talks on the use of imagery in global Muslim devotional practices.

Among them, a scholar discussed a new book in German titled “Was der Koran uns Sagt: Für Kinder in einfacher Sprache” (“What the Quran Tells Us: For Kids, in Simple Language”), produced by a Muslim scholar for German-speaking Muslim children. This child-friendly Quran is illustrated with many images, including the very same Ottoman painting of Muhammad receiving Quranic revelations that López Prater included in her class discussion and that Hamline administrators excoriated as disrespectful and Islamophobic.

A second colleague, who belongs to the Yemeni Shiite community, then discussed the Memory of Islam (Dhakirat al-Islam) Museum in Karbala, Iraq, which offers a Shiite-inflected narrative of Islamic history through the display of three-dimensional statues, many of which represent a veiled Muhammad. Pointing to Hamline’s attempts to ban such figural representations, this colleague looked up at us attendees and asked, off script: “Are we [Shiites] not Muslims, too?” There we sat, speechless, the pain of her query ricocheting against the room’s silent walls.

Although I, too, was left tongue-tied, I now ask myself this question: If Hamline University administrators had been present in that conference room, would they have had the audacity to respond to this Muslim scholar of Islam — who is no longer able to return to Yemen because of ongoing violence — in the negative? Would they have answered something to the effect of: “No, you are not a Muslim, we hereby declare you an Islamophobe, and we think it best that you are no longer part of the Muslim umma?” This excommunicative statement is not beyond the realm of the conceivable, since it was publicly uttered by a top Hamline administrator against López Prater in the wake of her showing her students two reverent premodern Islamic depictions of Muhammad, both of which in fact emanated from Sunni, rather than Shiite, contexts.

The Hamline incident is neither the first of its kind, nor will it be the last. This uncanny encounter — with some actors wishing to prohibit images of Muhammad and others pursuing academic research into the topic — captures an age-old moving equilibrium. It essentially pits a restrictive impulse against open-ended exploration. During my two decades of research into Islamic depictions of Muhammad, I have seen plenty of such top-down fiats flung against ground-up facts. And I have experienced similar contestations, including various actors — many of them non-Muslim — wishing to control the script and avoid “hurting Muslim sensitivities” by removing images from, and even censoring, a number of my scholarly publications.

Islamic depictions of the Prophet Muhammad circulate within this matrix of ideological yanking and pulling — perhaps more so than any other corpus of religious images, because of the discursive terrain they have been forced to inhabit ever since the Jyllands-Posten and Charlie Hebdo cartoon controversies, which were produced over the past two decades by cartoonists with the intent to shock and offend. Despite some individuals’ stubborn efforts to lump all depictions together, it is absolutely critical that we liberate iconic Islamic paintings from the yoke of (cheap) Euro-American satirical cartoons. Rejecting this facile yet flawed concatenation is the only way for us to embark on a long-overdue course correction.

So how is one to convey the history of Islamic images of Muhammad freed from today’s polarized politics? What are the challenges and pinch points of this particular academic endeavor, and what guardrails can be put in place to protect these historical documents along with the scholars who tend to them with nuance and accuracy?

Let us start with the Islamic paintings themselves, which provide the key data points for art historians. While images of Muhammad may have been made during his lifetime — as suggested by Islamic textual sources that mention a “chest of witnessing” (sanduq al-shahada) that contained a figural likeness of Muhammad confirming his prophecy — the earliest extant depictions date from the late 13th century. This six-century gap in evidence is possibly due to the fact that the famed Abbasid library, known as the “House of Wisdom” (Bayt al-Hikma), and its collection of manuscripts were destroyed during the Mongol invasion of Baghdad in 1258. This is a gaping lacuna, but there exist many similar material losses in the history of the world, especially within the context of warfare.

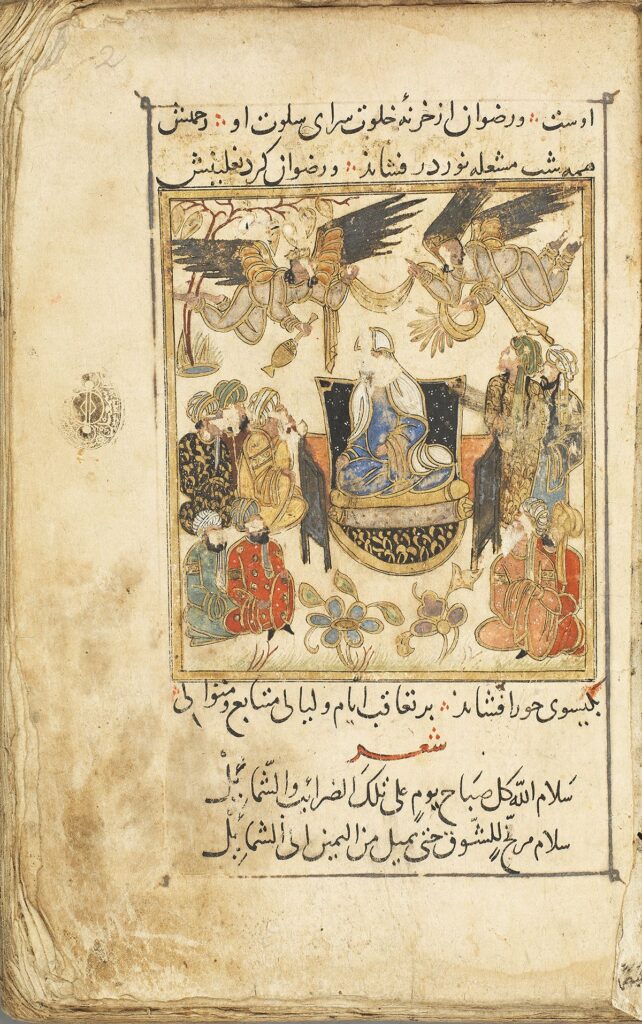

This temporal gap notwithstanding, one of the earliest surviving depictions of Muhammad is included in a manuscript of moralizing tales produced in Baghdad in 1299. The painting shows Muhammad enthroned and surrounded by listeners, while two angels hover above him as they endow him with a heavenly aroma and rays of light. Scent and light are often mentioned in medieval Islamic texts as proofs of the prophet’s divinely granted apostleship. The painter has also depicted all human beings, including Muhammad, with visible facial features, a representational practice that was normative in Persian-Islamic lands before 1500. However, as it has come down to us today, this painting is far from intact: Someone who owned or viewed it subsequently — though we know not when — gouged out every single face, perhaps in the belief that figural imagery is banned in Islam. Today’s Hamline polemic thus finds an echo in the physical damage sustained by a historical Islamic painting of Muhammad, itself having served as a litmus test for evolving beliefs about the matter.

This type of damage sustained by premodern paintings, however, should not always be interpreted as the desire to eradicate figural images, out of the fear that they may come to life or lead to idolatry. Indeed, the notion of a rigid and universal “Islamic iconoclasm” — that is, an irrevocable “Muslim urge” to destroy images — starts to crumble once further evidence is taken into consideration. Besides the many figural depictions created by and for Muslims, some Islamic paintings of Muhammad display smudges and pigment loss either because of their viewers’ pious handling or their sectarian fervor.

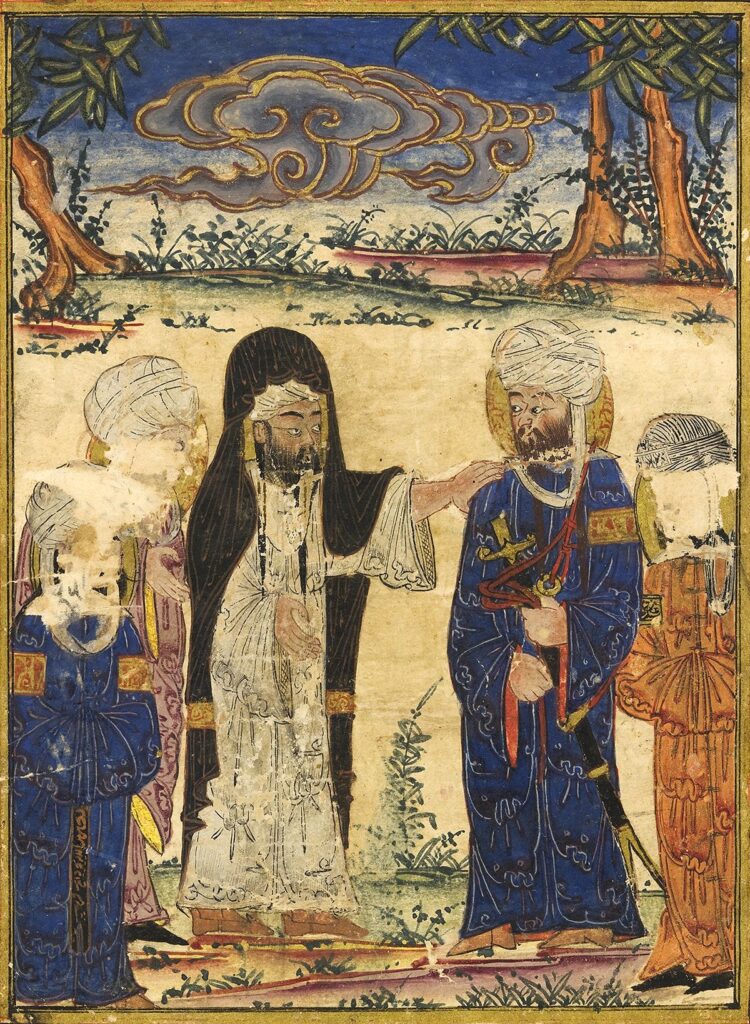

One of these images, which is included in an illustrated manuscript of al-Biruni’s “Chronology of Nations” produced in Iran in 1307, depicts Muhammad appointing his son-in-law and cousin Ali as his successor during his farewell pilgrimage. Muhammad is identifiable by his prophetic braids and black cloak (“burda”), while Ali carries his object-attribute, the bifurcated sword known as dhu-l-fiqar. Three other men accompany these protagonists, and they are likely the first three caliphs, Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman. Their faces, however, have been violently extricated from the picture. The viewer’s (or viewers’) assaults on their depictions may have occurred during the Safavid period — that is, the 16th or 17th century — at which time the Shiite ritual cursing of the first three caliphs and the burning of effigies of Umar were practiced in Iran. Thus, while the original painting was Shiite-inflected but nonetheless inclusive of Sunni figureheads, later Shiite actors decided to convert their oral maledictions into pictorial erasures, evincing a premodern “cancel culture” of sorts. Just as important, this pictorial evidence underscores two vital points: first, that the drawing of sectarian lines was not an immutable given but rather evolved over the centuries and, second, that the elimination of some “cursed” images symbolically maintained the immaculate conservation of others.

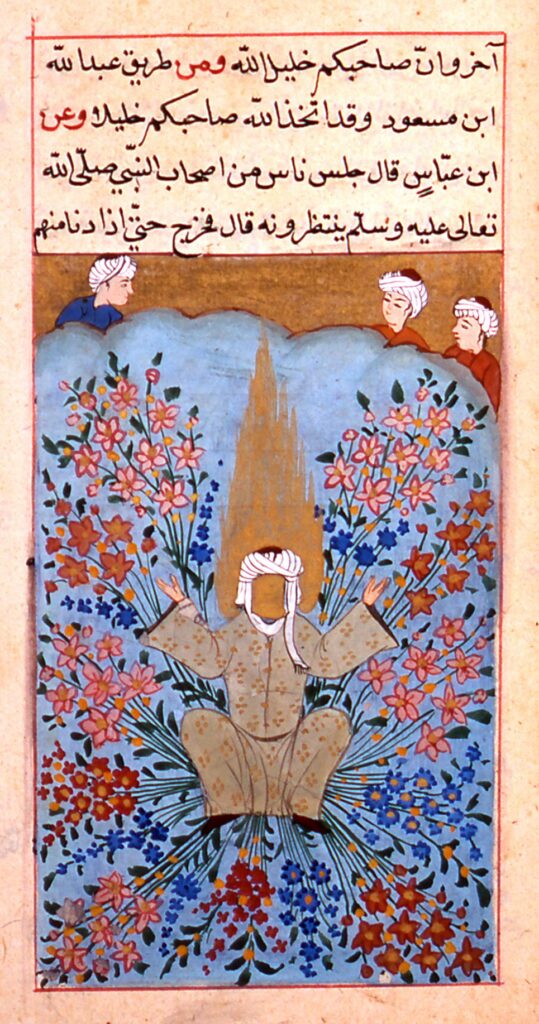

The destruction and preservation of images should not always be posited in diametric opposition. In fact, some iconoclastic acts create their own icons. Even images of Muhammad that depict his face covered by a white veil or overtaken by a golden blaze should not be interpreted as proof of a putative Islamic ban on prophetic representation (which, in fact, emerged only a decade ago in one Saudi Salafi fatwa). To the contrary, these abstracting symbols reveal a larger urge, by thinkers and artists alike, to imagine Muhammad in more-than-human terms: as a messenger who came into direct contact with God and therefore bears signs of the divine that render him too beautiful and brilliant to behold. This more metaphorical approach is not only supported by textual and iconographic evidence — it also is mentioned forthrightly in inscriptions added to the margins of illustrated manuscripts, in which, for example, an Ottoman commentator notes that a facial veil (“niqab”) has been added to an earlier Timurid painting of Muhammad out of respect (“tazim”) for his blessed face. This evidence helps to pinpoint an indigenous historical trajectory when it comes to depictions of Muhammad in Islamic lands. As of late, this moving equilibrium has migrated over to a U.S. campus, where non-Muslim administrators have entered the fray, taking an extreme anti-image stance that has no precedent in the Islamic record.

And yet Hamline administrators did not stop there: They also invited Jaylani Hussein, the executive director of CAIR-Minnesota, who is a Muslim civil rights leader and not a trained specialist of Islamic studies or art, to lead a community conversation about Islamophobia. During his remarks — which were recorded and shared publicly online — he called Islamic devotional paintings of Muhammad blasphemous, disgusting and racist as well as equivalent to Nazism and white supremacy. Devolving from the offensive to the obscene, he then equated Islamic depictions of the Prophet to “pedophilia art.” His invectives left us Islamic art historians gasping for air and fretting for the safety of Islamic paintings and those who study and teach them, above all Erika López Prater.

Scholarship is not just premised on academic freedom: It involves a high degree of responsibility in both word and deed. Academics do not throw care and caution to the wind. They avoid pontificating with toxic bravado, and they do not pervert evidence in order to wield influence or score political points. So back to the data we go.

Hussein also stated that a calligraphy of Muhammad’s name should have been taught instead of figural painting. Anyone armed with the most basic of information knows full well that Islamic art historians teach the history of calligraphy; we even show and practice with our students how to transcribe “Allah” and “Muhammad” so they can get a feel for the rhythm and flow of the Arabic script and, for those who don’t read Arabic, so they can delight in being able to decipher inscriptions over the course of the semester.

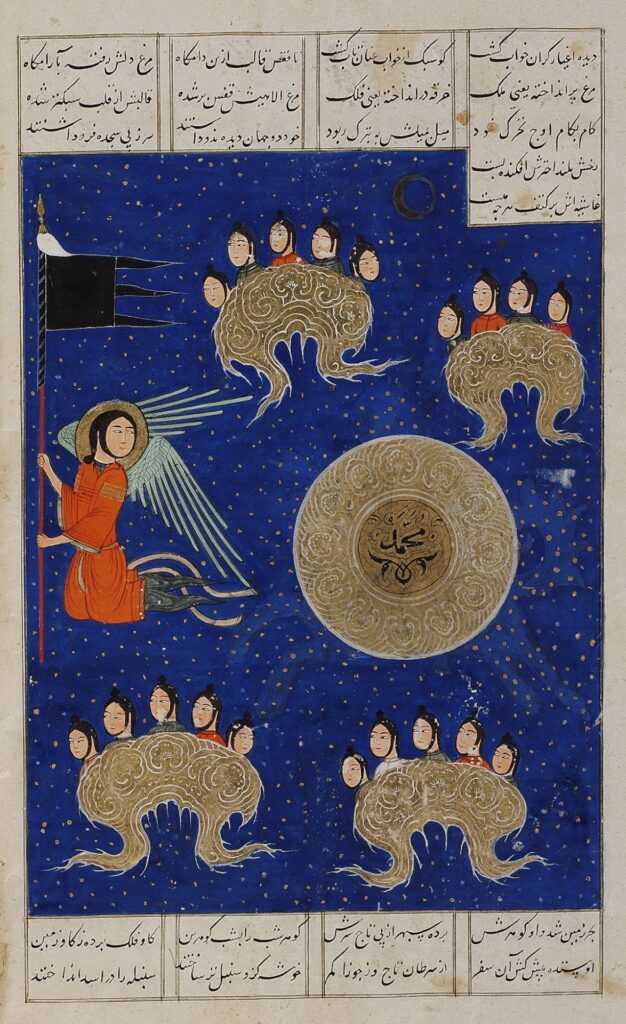

This is no zero-sum game: A calligraphy of Muhammad’s name is not mutually exclusive of a figural depiction. Just one quick look at the historical corpus reveals that some images purposefully blur these lines of artistic practice, as with one painting that depicts Muhammad’s celestial ascension. In this composition, the artist has shed the Islamic tradition of representing Muhammad in physical form, opting instead to depict him as a radiant disk inscribed with his calligraphed name. This visual stratagem cannot be explained as a mere avoidance of figural imagery, since the Angel Gabriel and other angels are shown as ethereal bodies fluttering in mid-air. It does, however, suggest a drive to depict Muhammad — whose name means “The Praiseworthy One” — as released from physical restrictions and temporal boundaries. Here, he is shown as if a cosmic luminary flickering in the night sky, a trope found in the folio’s accompanying verses penned by the famous 12th-century Persian poet Nizami.

This and other Islamic paintings invite us to resist cognitive splitting and taxonomic binaries to explore the apparent contradictions that historical data often place before us. This gray zone is not just productive. It is also provocatively rewarding, since it catalyzes a questioning of received truisms and one’s own expectations, thereby propelling a potential expansion and restructuring of the mind — that which we call the “learning process.” This prying-open of the intellect, of encountering a pinch point and then pivoting, is not always easy or smooth, but it is a basic duty for pedagogues tasked with supporting their students’ education and growth. Most of us, I would venture to guess, treasure our teachers because they gave us the mental training and tools to avoid the real-world harms that result from willful ignorance.

I myself have benefited from the support of my elders and peers over the course of my career, including during several major stumbling blocks that involved Islamic images of Muhammad. Besides the various book proposal rejections (“We won’t touch that topic with a hundred-foot pole,” said one editor) and article figures removed, pixelated or reduced to microscopic size, one incident stands out as particularly egregious. After 15 years of fieldwork in Iran, in 2015, I submitted an article exploring contemporary devotional images of Muhammad — which included a postcard I had purchased in a Tehran supermarket that went viral on Twitter during the Hamline debacle — to the journal “Material Religion.” Titled “Prophetic Products,” it sailed past peer review and headed into galleys. When the issue went live online, a colleague of mine wrote to ask me why my contribution was not included in the volume’s table of contents or line-up of articles. I scurried over to the internet, only to find out that a staff member at the publisher Taylor & Francis had made the last-minute executive decision to pull down my piece. I immediately reported the censorship to the journal’s editorial board. The board members could have stayed quiet and let it slide but instead notified the publisher that they would step down and let the journal sink if the omission were not immediately corrected. My article went back up online within a few hours, though not without someone at the publisher first inserting a trigger warning below my bio, warning readers about potentially controversial material, without my knowledge or consent. This episode somewhat foreshadows the Hamline debacle: In both cases, it took a coalition of voices to protest loudly, as well as the threat of legal action, for censorious actors to backtrack and, however speciously and belatedly, appear as if righting a wrong.

Through thick and thin, scholars must remain doggedly loyal to data, even if they are unpopular with certain segments of society at any given time and place. The Socratic, deductive method of academic inquiry requires that we approach historical facts with a humility of judgment, flexibility of mind and willingness to challenge and overcome our own biases. Indeed, every finding presents an opportunity to correct working hypotheses and articulate new lines of argument, the latter stemming from a sensitivity for history’s actors and their creative works as well as a deep respect for and commitment to our students’ intellects. Every time I myself face surprising or challenging finds — such as three-dimensional statues of Muhammad, of whose existence I knew not a week before writing this piece — I have no choice but to confront and fill gaps in my knowledge, and I cannot deny my students access to the whole picture when it comes to Islamic works of art in all of their richness and complexity. To my mind, this expansive scholarly praxis must remain a guiding ethos, as well as the ultimate sustainer of inclusive excellence, both on university grounds and in the world at large.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.