Old English battles weren’t particularly bloody. That is not to say that battles in early medieval England were not a bloody affair or that a person’s wounds did not drip blood. But the relationship between blood and violence in Old English literature is not what you might think. Blood doesn’t pour from Christ’s wounds, and battlefields are not slick with gore.

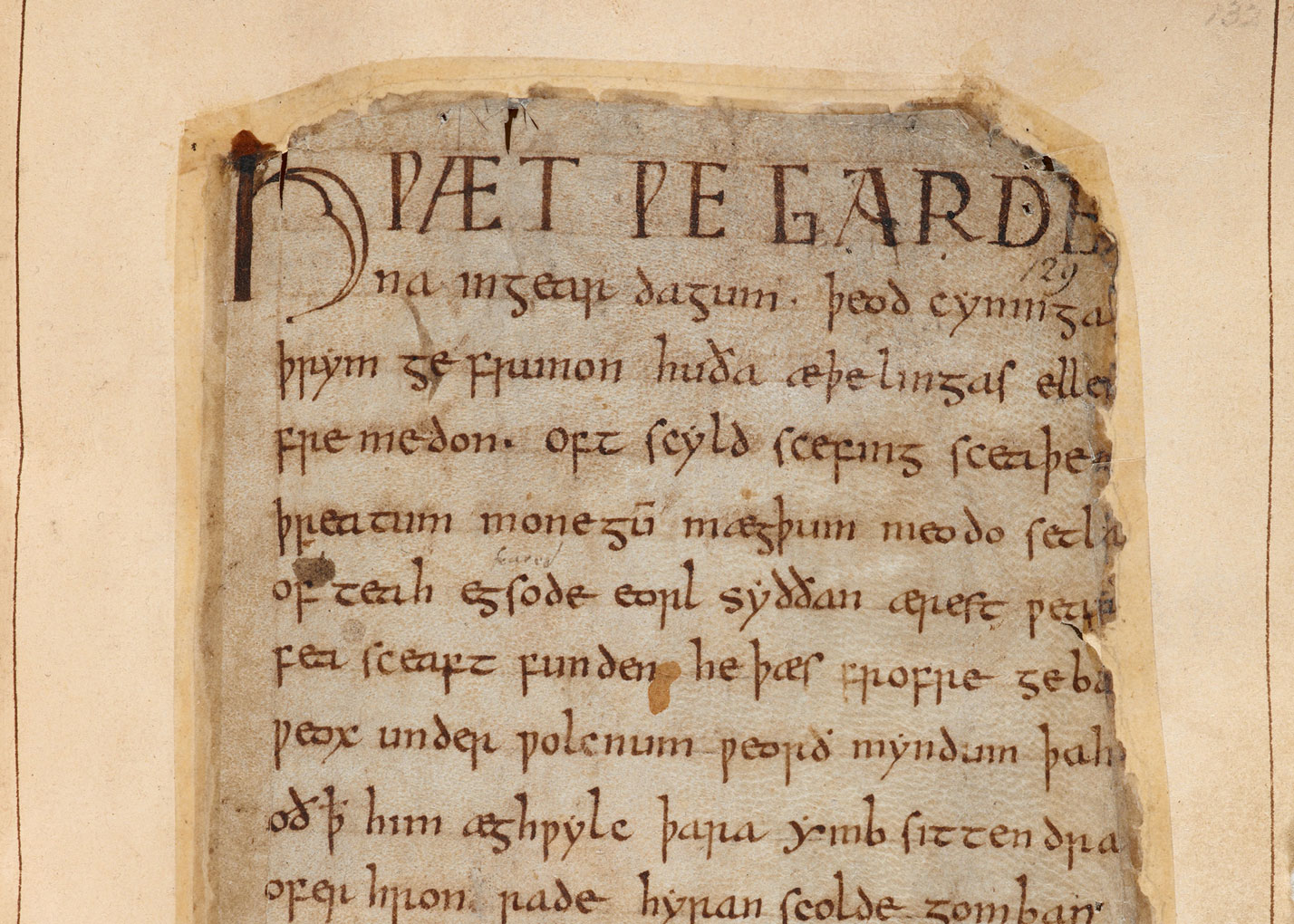

Old English is often confused with Shakespeare’s English (early modern) or Chaucer’s English (Middle English), but it is far older, the language of the poem “Beowulf.” Old English was the vernacular of early medieval England (c. 550-c. 1150). It’s closest in structure to Frisian, a language from what is now the Netherlands and northwest Germany, so you might recognize more words if you speak Dutch or German. While Latin was the language of the Christian church and of learning, Old English (or “englisc,” as it was called at the time) was what most people spoke. We know little about the earliest Old English, since most of the extant texts are in manuscripts from the 10th and 11th centuries.

We often think of languages as expanding their vocabularies over time. After all, the latest update of the Oxford English Dictionary has nearly 700 new words, senses and phrases, with updates being released four times a year. (Some of the Oxford English Dictionary’s latest additions are “tweakable,” “vaxxed” and “dinosauric.”) In early medieval England, “telephone” and “computer” were not even concepts, much less words. It’s easy to see how a language’s lexicon would increase vastly over a millennium.

But languages also lose words. People are no longer “ælf-scyne” (“elf-shining” or radiantly beautiful). We no longer have “gafol-fisc” (literally “tax-fish,” or fish paid as tax or tribute).

While modern English’s blood words are limited to “blood” and “gore,” Old English has “blod,” “swat,” “heolfor,” “dreor” and “sawul-dreor.” The most common and prosaic of these is blod. Both blod and swat appear in “leechbooks” (medical texts), but only blod means “blood” in this prosaic context. (In leechbooks, swat refers to either perspiration or plant juice, never to blood.) Swat, along with heolfor and dreor, means “blood” in poetry. “Sawul-dreor” is often translated “life blood,” but it literally means “soul blood.” Although medieval poetry frequently depicts the soul and body as separate (even opposing) entities, the soul is not entirely incorporeal, and sometimes blood even represents the soul physically.

Of all the Old English blood words, there is one that appears specifically in scenes of violence. The Toronto Dictionary of Old English defines heolfor as “blood, gore.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines “gore” as “blood in the thickened state that follows effusion” and in poetry often “blood shed in carnage.” When used in a poetic context, modern English “gore” is blood shed through violence, like the word heolfor in its Old English contexts. (“Gore,” incidentally, does not have this definition until the 16th century, and in the medieval period it meant “dung,” “ordure” or “filth.”)

While it is true that heolfor always coincides with violence, it does not follow that heolfor (or any Old English blood word) is always present in violent scenes. None of the usual motifs for Old English heroic poems include bloodstained or bleeding bodies. In fact, the three Old English poems specifically about battles (“The Battle of Maldon,” “The Battle of Brunanburh” and “The Battle of Finnsburh”) collectively have only two blood words.

“The Battle of Maldon” is a poetic account of the battle between the English and the Danes near Maldon in Essex in 991. Most likely written in East Anglia in the late 10th or early 11th century, the poem describes a full-scale battle that occurs when the ealdorman Byrhtnoth refuses to pay tribute to the Danes. The Old English scholar Alice Jorgensen notes the physicality of the poem’s violence; bodies have “solidity” and “spatial depth.” Yet for all the physicality of the bodies, blood is mentioned only once in the entire poem.

Instead, the descriptions of battle emphasize weaponry. “Wæpen” (weapon) appears 10 times throughout the poem. Aside from the general term wæpen, the poem contains an assortment of specific types of weapons — everything from a bow (boga) and arrow (flan) to a spear (gar), sword (swurd) or shield (bord). Weapon words appear a whopping 70 times within 325 lines of verse. Detailed descriptions of weaponry — not bleeding limbs — are essential to the poet’s depiction of this violent event.

Blood’s one and only appearance in “The Battle of Maldon” occurs when a young warrior named Wulfmær removes the spear from Byrhtnoth’s fatal wound: “Beside [Byrhtnoth] stood a young man not fully grown, a boy in battle, who very valiantly drew from the warrior the bloody spear [blodigne gar], the son of Wulfstan, young Wulfmær.” The adverb used to describe Wulfmær’s action is “caflice,” which is defined as “quickly, hastily, stoutly, manfully, valiantly.” Wulfmær is quick but also brave, and even though the poet emphasizes his youth, calling him “unweaxen” (not grown), “geonga” (young) and a mere “cniht” (youth), the warrior has left childhood behind. If the cniht Wulfmær is truly young, perhaps this is the first time he has witnessed death on the battlefield, making the moment of seeing blood on a spear particularly poignant and disturbing.

There are plenty of violent moments in the poem that logically would include the spilling of blood: “hyssas lagon” (men lay dead); “wund wearð Wulfmær” (Wulfmær was wounded); warriors “mid billum wearð … swiðe forheawen” (with swords were greatly cut down); a spear went “þurh ðæs hysses hals” (through the man’s neck). These are only a handful of examples of combat and injury in the poem, none of which uses blood imagery to depict or emphasize the violence.

In contrast to “The Battle of Maldon,” the Old English poem “Exodus” includes some particularly bloody moments that coincide with violence. When the Egyptians try to follow the Israelites across the Red Sea, God’s power and will are manifest in the violence of the “flod-egsa” (flood-terror). The Latin Vulgate Bible’s description of this event is bloodless — which makes sense for death by drowning — but in the Old English poem this scene is soaked in blood and gore. When medieval theologians and poets translated the Latin Vulgate into Old English, they sometimes remained faithful to the original text and other times abridged, expanded or even reinvented certain episodes. The Vulgate (in the Douay-Rheims translation) describes the Egyptians’ demise:

“[A]nd behold the Lord looking upon the Egyptian army through the pillar of fire and of the cloud, slew their host, and overthrew the wheels of the chariots, and they were carried into the deep.”

Here there is neither blood nor gore, only a pillar of fire and a dark cloud from which God works his power over the ocean waves. As the Egyptians flee:

“The waters came upon them, and the Lord shut them up in the middle of the waves. And the waters returned, and covered the chariots and the horsemen of all the army of Pharao[h], who had come into the sea after them, neither did there so much as one of them remain.”

The Israelites praise God in the canticle of Moses, describing the Egyptians’ fate:

“Pharao[h]’s chariots and his army he hath cast into the sea: his chosen captains are drowned in the Red sea. The depths have covered them; they are sunk to the bottom like a stone. … And with the blast of thy anger the waters were gathered together: the flowing water stood, the depth[s] were gathered together in the midst of the sea. … Thy wind blew and the sea covered them: they sunk as lead in the mighty waters. … Thou stretchedst forth thy hand, and the earth swallowed them.”

God’s might is clearly manifest through the drowning of Pharaoh’s army, with the divine harnessing of wind and waves. Nowhere does blood appear in these descriptions.

Unlike the Vulgate’s narrative, graphic moments of bloody violence appear in the Old English poem “Exodus.” When the Egyptians arrive at the “sin-calda sæ” (ever-cold sea), they see “beorh-hliðu blode bestemed” (blood-soaked mountains) and “holm heolfre spaw” (the ocean spewing out gore). The water is “wæpna ful” (full of weapons), although these weapons are not actually doing anything. The sky is “heolfre geblanden” (blended with gore), and the sea is a “blod-egesan hweop” (whip of blood-terror). The medieval literature scholar Richard Trask argues that the “unrealistically gory” drowning scene relates to the imagery of the world’s destruction on Judgment Day. In these scenes from “Exodus,” blood does not represent literal blood shed in violence but rather God’s judgment, a violent purgation of sin and moral ordure.

The most meaningful blood in the perspective of a medieval Christian would have been Christ’s blood, which was celebrated at Mass with the receiving of the Eucharist.

Christ’s bleeding wounds became increasingly central to medieval devotion, beginning in monasteries in the 11th and 12th centuries and spreading widely during the later Middle Ages. In 1264, the Eucharistic feast of Corpus Christi was established, a celebration of Christ’s blood that was spilled to save humankind. This sacred blood became an increasingly important symbol over the 13th and 14th centuries to Christians across Europe.

Christ’s death would probably not have been bloody in actuality. The historian Caroline Walker Bynum writes, “As inhabitants of the ancient world knew well, the crucified die by suffocation.” Death was not caused by blood loss. There were a number of ways someone could die from crucifixion (exhaustion, shock, infection, etc.), but Bynum is referring to death by asphyxia, when the hyper-expansion of chest muscles and lungs prevented an adequate intake of oxygen. While there was probably some blood present at the crucifixion from the nails and spear wound, there is no particular reason for Christ’s death to be bloody in artistic depictions.

In the later Middle Ages, bleeding wounds signified what the historian Miri Rubin calls “the most complete unmaking of the body … the ultimate offering, ultimate sacrifice.” Bynum notes that by the late 14th century, devotion to Christ’s wounds had grown extensively, and Christians were even instructed to calculate the number of prayers they needed to say by the number of Christ’s lesions and blood drops. The popularity of the cult of the five wounds peaked in the late Middle Ages, with the post-mortem wound in Christ’s side the most venerated of all.

Depictions of Christ’s crucifixion were increasingly bloody in the later Middle Ages. The crucifixion came to be valued as the true moment of humanity’s salvation, even more so than Christ’s resurrection and incarnation. Christ’s power lay in his ability to withstand and overcome suffering, yet descriptions of his moment of victory increasingly emphasized the human experience of pain. Devotional writings of the late Middle Ages turned Christ’s wounded body into the focus of love, sacrifice and suffering, with which a human could intimately self-identify.

Before this bleeding Man of Sorrows, Christ was depicted as a triumphant warrior god. It was not that Christ’s human experience of pain and suffering was not recognized in early medieval England. His sacrifice was seen as both a demonstration of martial ability and an act of love. And a warrior in Old English literature need not be bloody, as is clear from the battle poems above.

However, there is one example in Old English of blood words accompanying Christ’s death. The poem known as “Christ III” describes a cross appearing on Judgment Day, bloody from Christ’s sacrifice, in a passage that uses three different blood words. (The text is difficult to translate since there are not enough modern English synonyms available.)

“Sad-spirited, sin-stained men will behold themselves with the greatest sorrow. It will be no mercy to them that before those strange people will stand the rood of our Lord, the brightest of beacons, soaked with blood [blode], the pure blood [dreore] of heaven’s king, sprinkled with blood [swate], which will shine clearly across the vast creation.”

The rood or cross is soaked with Christ’s blood, but the poem mentions neither the means of nor the bodily harm caused by violence. And even though three Old English blood words are used, heolfor (gore) is not one of them. Here blood is strangely disconnected from the body. Its appearance has less to do with violence or redemption than it does with judgment.

Sinners in “Christ III” are punished severely, but their torments are not bloody. Instead, their souls are tested with “hot and slaughter-greedy fire.” Even when Christ wields a “sigemece” (victory sword), striking down devils and the sinful, no blood stains his blade. On Judgment Day, souls will fall and burn, bound in flame and cursed to perdition, but it seems that not a single drop of human blood is shed. Blood imagery appears until the moment of judgment. Afterward, when the sinners are in hell, blood, symbolic of judgment, is irrelevant.

Judgment Day rains and flows with blood in three Old English homilies from the 10th century, but similarly, the hellish torments described are bloodless. There is no shortage of descriptive terms for hell’s horrors, but even injuries from “the worst wild beasts that wound your soul” do not result in bloodshed. Blood is a symbol of judgment, not the result of violent punishment.

In Old English, only Christ has blood that is “dyrwurþe” (precious). No other blood, not even that of the saints, has such worth, equal in value to the saved souls of humanity. Blood appears to remind sinners whom they must follow for salvation on Judgment Day. A vision of dyrwurþe blood is not a threat but a reminder of humanity’s debt, a mark of God’s judgment.

Even nature can remind humans of their blood debt to God, with blood pouring down with the rain, obscuring the sun, and oozing from tree bark. In “Christ III,” the crucifixion describes trees that bleed, not a human body:

“Ða wearð beam monig blodigum tearum

birunnen under rindum reade ond þicce;

sæp wearð to swate.

Then many a tree became bedewed with bloody tears under its bark, red and thick; the sap was turned to blood.”

These bleeding trees are a reference to a verse in IV Ezra (II Esdras), one of the lesser-known apocryphal books originating in the late first century, which says in Latin: “Et de ligno sanguis stillabit” (“Blood shall drip from wood”). The 17th-century English poet and intellectual John Milton interprets this verse: “[T]he deadness of men to all noble things shall be so great, that the sap of the trees shall be more truly blood, in God’s sight, than their hearts’ blood.” The trees become increasingly “human” as humans become less so.

Bleeding trees signal God’s judgment, but they also demonstrate a kind of transference — in this case, transferring a human quality to a nonhuman entity. In Old English texts, blood interacts with and affects the surrounding world, transferring qualities of sanctity and sin, health and illness, humanness and divinity.

In medical remedies, blood can be used to transfer a person’s ill health from their body. A remedy for “onfealle” (swellings) says to write the patient’s name on a stick of hazel wood, then to fill it with some of their blood. One leechbook instructs, “Throw it over your shoulder or between your thighs into flowing water.” A remedy for a spider bite works similarly: the patient’s blood should be applied to a stick, which is then tossed over a “wagon road.” Symbolically then, disease or harm is transferred from one’s body to a stick and is physically cast away across a boundary line. Treating the blood outside of the body is meant to have an effect on the body by extension.

In the Old English “Passion of St. Christopher,” a saint’s blood restores a blind man’s sight. A pagan king is torturing Christopher when he is suddenly blinded by two arrows shot into his eyes. The saint tells him to visit the place where his own martyr blood will be spilled, and to apply some of this bloody earth to his eyes. Not only is the king’s physical sight restored, but he also receives the spiritual vision he previously lacked. St. Christopher’s piety and faith is transferred through his blood to the king’s eyes, and the king’s eyes are opened to the Christian faith.

Blood germinates new life in Old English literature. Another saint’s blood is spilled in the Old English poem “Andreas,” in which St. Andrew is tortured by cannibalistic pagans. Not only does Andrew’s blood pour forth, but it also transfers sanctity to the earth itself. Blossoming groves adorned with leaves stand where Andrew’s blood falls, blood spilled in faith and devotion. St, Andrew’s blood, the tangible embodiment of his holy soul, soaks into the earth, and from it grows trees of spring, life and rebirth.

We see a different kind of plant grow when Cain kills his brother Abel in the Old English poem “Genesis A.” The earth swallows up the “cwealm-dreor” (slaughter-blood) spilled by Cain, blood of hostility, murder and fratricide. When Abel’s blood soaks into the earth, “wea” (woe) is germinated, and a tree of every evil takes root. Its harmful branches spread across the world. This first time that blood mingles with earth in the world, murder and woe take root among humankind. The final time that blood and earth will mingle is on Judgment Day when the sins of humanity — every evil that Cain brought into the world — are ended once and for all.

The relationship between blood and violence in Old English is far from straightforward; one is not simply the representation or the result of the other. Blood doesn’t gush from battle wounds or pour from Christ’s body. Whether material or metaphysical, blood in Old English texts is most notable for its quality of transference. Old English literature isn’t necessarily bloody, but wherever blood does appear, it’s there to transform the world, influencing all who touch and see it.