On July 23, Egypt marks the 70th anniversary of its “July Revolution,” the 1952 coup that dethroned the country’s king and replaced him with a military regime whose inheritors endure in power today. Egypt’s premier old movie channel, Rotana Classic, will commemorate the occasion by playing, as it does every year, director Ezz El-Dine Zulficar’s 1957 melodrama “Return My Heart” (“Rudd Qalbi”).

The film, and the 1954 novel by Yusuf Sibai on which it is based, looks to the 1948 war between an uneasy Arab coalition and the newly declared state of Israel to help explain the overthrow of the ancien régime. Shoukry Sarhan stars as Ali, the son of a poor gardener on an opulent estate. Sent to fight in Palestine in May 1948, Ali initially believed official predictions of a rapid Arab victory over the Zionists. That victory never comes. The film’s hero, heartbroken and disillusioned, swears allegiance to a group of fellow veterans plotting to seize control of the country from the leaders who presided over the catastrophe. These men, the Free Officers, triumph at the end of the film as a radio voice proclaims the exile of King Farouk and the dawn of a new era of justice and social equality.

It might seem paradoxical that the defeat of the Arab armies, including Egypt’s, would give way to military rule less than four years later. This rapid reversal of fortune could not have occurred had a clear separation not taken root in public consciousness between the army and the Egyptian political establishment, symbolized by the palace. The former was seen to have suffered the loss, the latter to be culpable for it.

As Egyptians worked to make sense of the unexpected defeat, one explanation came powerfully to the fore. This was the notion that Egypt had lost the war in Palestine because political leaders had procured, profited from and knowingly supplied their own troops with dysfunctional weapons. It was a succinct and broadly plausible narrative, folding in long-standing grievances many Egyptians harbored toward the country’s politicians and well-connected economic elites, as well as the British colonizers. This version of events is written into “Return My Heart,” serving to crystallize a link between the war and the overthrow of the monarchy. Of Ali and his fellow soldiers, a voiceover intones: “They did not battle Israel, and Israel did not defeat them. Rather, their king and traitors among their countrymen defeated them.” An artilleryman’s gun explodes, killing him instead of his enemy. A friend of Ali’s recounts a conversation with a soldier from his unit lying wounded in a field hospital. “You know what he told me?” he asks the film’s protagonist. “‘I’m afraid I won’t die from my wound, but I’ll die from the medicine! It’s not far-fetched to think that the medicine would be defective, just like the guns our officer is using!’” The same friend, Sulayman (played by Kamal Yasin), will later initiate Ali into the Free Officers pact.

The story of a regime undone by its own dysfunctional weapons permeates Egyptian popular culture. In cinema, besides “Return My Heart,” it appears in “Land of Heroes” (“Ard al-Abtal”) (1953), “God Is With Us” (“Allahu Mana”) (1955), “River of Love” (“Nahr al-Hubb”) (1960) and “Bloody Destinies” (“al-Aqdar al-Damiya”) (1982), among others. Today, the phrase “defective weapons” (al-asliha al-fasida) remains so familiar a touchstone as to serve as metaphor: In a recent 10-part series of essays for The New Arab (al-Araby al-Jadid), for example, critic Belal Fadl invokes the reference figuratively to depict the Egyptian film industry as an impotent force in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Yet the defective weapons are more than a cultural trope or cinematic plot device. The narrative in which they center is widely credited with stimulating sufficient public disgust with the monarchy after the war to ensure widespread support for the coup in 1952.

The fact the defective weapons story served as a compelling explanation for the Palestine debacle does not mean it was entirely true. Memoirists who participated in the war and later analysts have largely concluded that while Egypt did acquire useless or malfunctioning arms, some in shady deals, this alone did not explain the loss. The consensus lies in conventional factors like poor intelligence, inadequate training, low morale and an inexperienced high command. Tharwat Okasha, a young military intelligence officer during the war in Palestine who joined the Free Officers and later served as minister of culture, dismissed the allegations as “surpassing reality.”

The defective weapons might not have been decisive in war, but they were decisive in history. They provide a prime opportunity to examine the relationship between rumor and regime change — as a catalyzing force or, more conservatively, a reinforcing one. But it is just as important to understand how and why this narrative stuck. Many rumors, rich as they may be, do not. What were the conditions that fostered the emergence of the defective weapons story and imbued it with such explanatory power?

Historians, journalists, governments and citizens have battled over narratives of 1948 — the Nakba for Palestinians, the War of Independence for Israelis and the Palestine War (“Harb Filastin”) for Egyptians — for seven and a half decades. But how and among whom information circulated during the war itself remains, surprisingly, poorly understood. Such gaps in knowledge are especially prominent when it comes to the information landscape in the surrounding Arab states, including Egypt. One reason is that Egyptian records of the war have never been opened for public scrutiny. Yet this is the terrain on which the story of the defective weapons developed.

War broke out in Palestine at the culmination of what was, in Egypt, a decade of dissatisfaction and distrust. In the 1940s, the country witnessed a string of political assassinations, a wave of labor activism, a frustrating impasse in negotiations over British withdrawal and conspicuous capitalist excess among elites. Five senior Egyptian officials, including two prime ministers, were killed in Cairo from February 1945 to December 1948. The end of World War II led to ballooning unemployment, the cost of living soared, an agrarian crisis rocked the countryside, and a cholera epidemic swept the country. Discontent found expression in anticolonial nationalism, labor organizing and religious fervor, prompting the formation of groups whose interests sometimes converged and sometimes clashed violently. These tensions forced Egypt’s political class into a defensive crouch, and what standing troops were available were deployed to maintain public order. Authorities’ intense focus on internal security was among the reasons Egypt was ill-prepared to fight a war in Palestine.

King Farouk had assumed the throne upon the death of his father, Fuad, in 1936. This was to be the last such succession for the Mehmed ʿAli dynasty. The Anglo-Egyptian Treaty was concluded the same summer, reducing but preserving the British military presence and granting the imperial power additional privileges in case of war. The young monarch presided over what political scientist Robert Vitalis has called “a long last summer for Egyptian oligarchic capitalism,” his lavish dinner parties and taste for languid summers in Capri and Biarritz symbolic of a heyday of privatization and profit-seeking. The Wafd, long Egypt’s leading political party, was riven by factionalism.

In February 1947, Britain announced its intention to end its mandate in neighboring Palestine and let the United Nations chart a course forward. The U.N. Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) deliberated that autumn amid a heavy Zionist pressure campaign on member states. On Nov. 29, 1947, the U.N. General Assembly voted by a two-thirds majority for UNSCOP’s plan to partition Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab; all six Arab member states voted against it. But as prospects for implementing the resolution rapidly dimmed, so did Egyptian chances of avoiding embroilment in a war. Street protests escalated and a growing number of Arab volunteers independently left to join escalating clashes in Palestine. Waiting to commit troops would leave Egypt in awkward isolation vis-à-vis the other Arab states. On May 11, Farouk ordered Minister of War Muhammad Haydar Pasha to prepare for deployment. On May 14, Israel declared independence, and the next day, Britain formally withdrew. A few hours later, 10,000 Egyptian soldiers crossed into Palestine at Rafah.

The Egyptian army had not participated in a significant foreign combat operation in decades. Still, the invasion seemed to officials to be more a distraction than a recipe for disaster. Once the decision was made, Haydar Pasha began boasting that Egyptian forces would be marching through the streets of Tel Aviv in two weeks’ time. Haydar Pasha was an appointed ally of the palace, not a career soldier — a fact that caused considerable friction with senior officers. Muhammad Naguib, Egypt’s first president after the Free Officers’ coup, later related this in “My Word for History” (“Kalimati li-l-Tarikh”). “You don’t recognize me as head of the army,” he says Haydar Pasha told him. “When a police officer is appointed to lead the army,” Naguib replied, “it means one of two things: either a lack of competence or that the entire army is unimportant. Both are humiliating.” Regardless of what was taking place behind the scenes, however, the Ministry of War’s rosy prognosis shaped the public’s perceptions of the impending fight and, importantly, those of the soldiers headed into battle.

The same message was conveyed at the outbreak of war by the palace’s in-house press attaché, Karim Thabit. Thabit came to the post as editor-in-chief of the newspaper al-Muqattam, which Egyptian nationalists had long maligned for British subsidies and sympathies. Al-Muqattam, like all the metropole’s major newspapers, greeted the formal onset of hostilities with confidence. “It is not a war,” its May 13 headline read, “but a restoration of security and order, and prevention of massacre and destruction.”

Thabit was the first to serve formally as palace press attaché, a position established in 1946 as Farouk worked to burnish his stature within the newly formed Arab League. The creation of the role corresponded with changing public expectations. Increasingly, citizens expected an account from government officials about affairs of the state. As the country headed to war, Thabit’s appointment ensured that the palace was now equipped to provide one.

There was no dearth of news from Palestine in the first weeks of the war. In Egypt, as in several other Arab countries, the Council of Ministers and Ministry of Defense issued a stream of short official updates on operations, sometimes more than once a day. An unprecedented range of media — among them newsreels, radio, aerial photography and embedded newspaper reporters — brought the conflict home to Egypt. With a brief exception in the 1890s in Sudan, this was the first time Egyptian reporters were reporting from a battlefield where Egyptian troops were engaged in combat. Just hours after the war began, the newspaper Al-Ahram placed its readers in the cockpit of an airplane circling a smoldering Tel Aviv. Its correspondent, Sami Hakim, hung a mere 7,000 feet above the city center — close enough, he said, to see buildings crumbling in the Zionist stronghold. The Ministry of Defense’s Department of Public Affairs also hired a photographer to accompany troops to the front and provide images of operations to the media, another first.

Stills were not the only images that helped reinforce pronouncements of imminent victory. “Egypt’s Talking Gazette” (“Jaridat Misr al-Natiqa”), a newsreel produced by leading film production house Studio Misr, brought to life the photos appearing in the papers. In fact, they often depicted identical scenes, which suggests that the photographer and cinematographer were probably shepherded around the front together. While Arabic-language newsreels had been produced in Egypt sporadically since the 1920s, their audience was growing with the rapid expansion of the domestic film industry.

The event most depicted in various Egyptian media in the first stage of the war was the fight for Deir Sneid, 7 miles north of Gaza City. The visually arresting wreckage of the battle provided apparent proof that the Egyptian army was well on its way to Tel Aviv. In one episode of “Egypt’s Talking Gazette,” the camera lingered on the shell-scarred water tower of Deir Sneid, now crowned with the star and crescent standard of the Egyptian monarchy. An upbeat narrator proclaimed the army was “recording victory after victory.” Another newsreel showed Farouk rolling into the recently shelled town in his convertible — binoculars resting on his corpulent chest, full-moon sunglasses perched beneath his peaked cap. He was “delighted” with what he had seen.

But the exuberant early projections disseminated in Egyptian media proved false. Two weeks after the Arab armies entered Palestine, they were not in Tel Aviv. Instead, a U.N. ceasefire was announced on May 29. The U.N. then announced an embargo on arms imports to Palestine and neighboring countries, adding to a similar embargo the United States had imposed the previous December. Agents of the nascent Israeli state managed to circumvent them, acquiring weapons from what was then Czechoslovakia as well as Spain and Italy. The Arab states, however, including Egypt, struggled to do the same. As the conflict’s time horizon extended from weeks to months, this drove an increasingly desperate search for arms.

The stagnation signaled by the restless ceasefire, the first of several, also began to stir doubts. Rumors gestated in the cognitive dissonance that lay between the steady clip of optimistic reports disseminated by the palace, the Ministry of Defense and the press, and what people could see was not such a quick operation after all. Hints of faltering confidence can be read between the lines of vigorous praise for the Ministry of Defense in Sayyid Farag’s “Our Army in Palestine” (“Jayshuna fi Filastin”), the first book on the war to be published in Egypt. “Our Army,” rushed out in September 1948, equated government sources’ acknowledgment of certain battlefield misfortunes with proof that the public “would be informed of the truth of the matter without dupery or deception.” But Farag seemed to be prescribing this conviction, not describing it. “The country has received all media with trust and assurance,” he declared.

The last phase of intense fighting lasted from mid-October to mid-November. Replenished with weapons from abroad, the Israelis now had the upper hand, and they closed in on the Arab armies’ remaining positions. The Egyptians, having held out remarkably long around the Gazan village of Faluja, were besieged and depleted. On Nov. 12, Egyptian news announced the king’s promotion of the commander at Faluja, Sayyid Taha. But two days before the promotion, Taha had already cabled Cairo with bad news, after Israeli forces had captured another Egyptian stronghold in the area. “Our position is worsening from one moment to the next due to the enemy’s constant and uninterrupted assault,” he communicated. Begging for an urgent reply, he said, “I am doubtful of the possibility of continuing more than this.” Back in Egypt, news reports documenting the Faluja resistance soon went quiet. Before long, the war was over.

The Faluja contingent’s final homecoming, celebrated in March 1949, produced a dissonant convergence of the steady thrum of good news that had circulated on the home front and the dire realities of the battlefield. Taha’s troops returned to Cairo on March 10. In a newsreel about their homecoming, citizens jammed the streets in celebration. Taha kissed the king’s hand and led the troops in saluting and chanting, in unison, “Long live Farouk, King of Egypt!” However, the jubilation masked an unhappy reality. The newsreel’s narrator alighted on a euphemism, gliding quickly past the “dreadful events” that had not “dampened … the people’s indomitable spirit.”

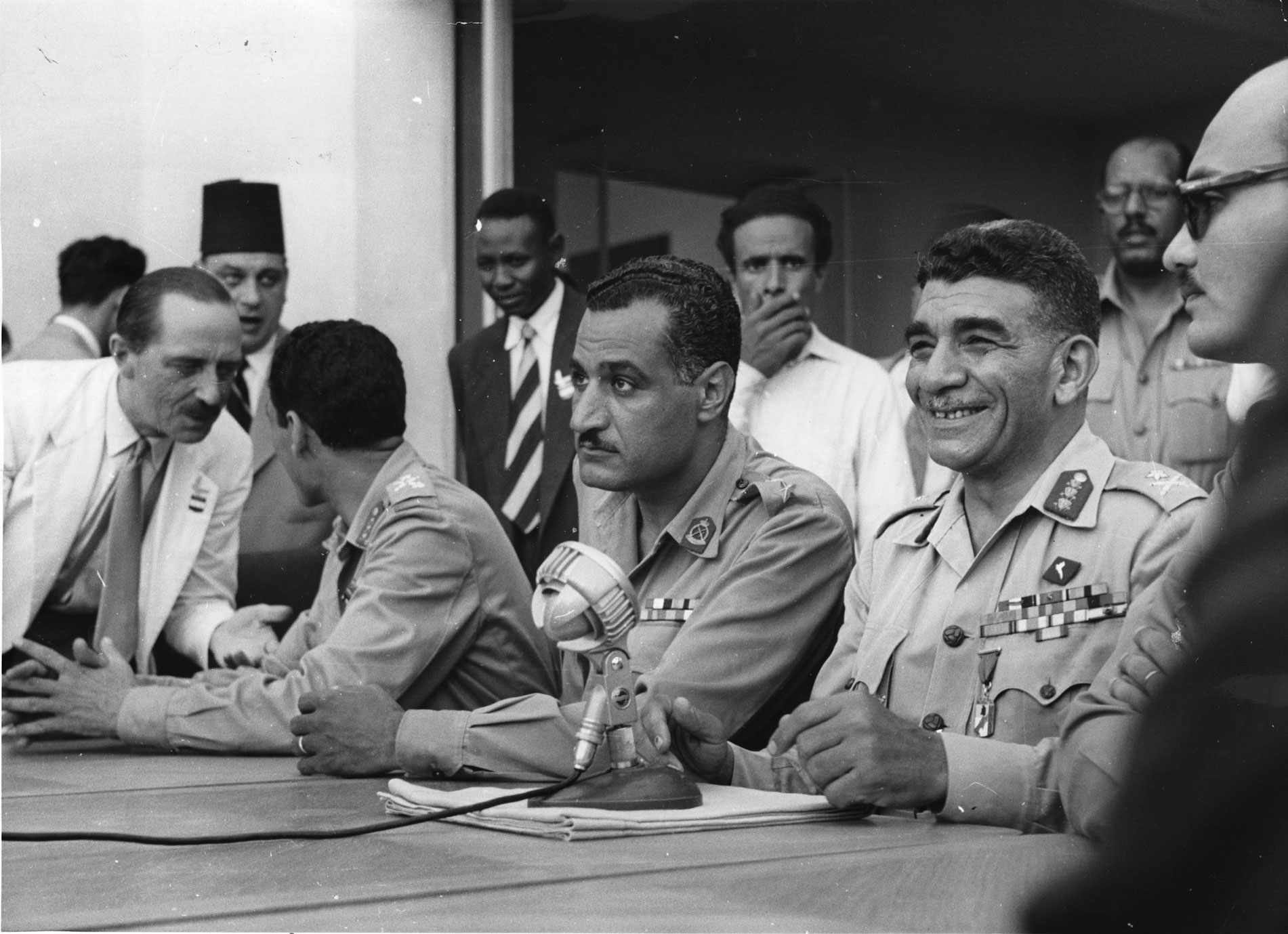

Yet several who fought in Palestine described a prevailing sentiment among the returning soldiers that was far from triumph. The army “had lost confidence in itself; it had lost confidence in its leadership; and it had lost confidence in its government,” Kamil Sharif wrote in 1950. Contradiction and confusion were “made worse by what the soldiers heard about defective weapons and the dirty role that top brass and bigwigs had played” in the affair. Sharif, 24 at the time, had studied journalism in Cairo and Geneva, then volunteered with the Muslim Brotherhood to fight in Palestine. Growing resentment between the army and the brotherhood likely emboldened Sharif to describe the defeat so bluntly. But Sharif’s assessment mirrors what others were saying — first privately, then louder and more publicly. Among these was Gamal Abdel Nasser, who, along with several other Free Officers, was part of the contingent besieged at Faluja. The obfuscation of information and dissemination of disinformation figured prominently in Nasser’s later depiction of a conflict marred by “bewilderment and incompetence.” He would accuse the high command of describing “in the minutest details,” he claimed, “how the troops had stormed the settlements of the enemy cheering ‘His Majesty the commander-in-chief!’” when this was “emphatically what did not happen.” Even radio programs broadcast from Cairo early in the May assault on Deir Sneid “contained a painful lie,” he wrote, “for our forces had not yet occupied the settlement.”

While the defeat felt bad, being lied to about it felt worse. Back home, the soldiers’ sense that they had been duped crept through society before finding concrete expression in the story of the defective weapons. Like the claims of generals and politicians at the war’s outset or official pronouncements of victory broadcast prematurely on the radio, the faulty arms were empty promises disguised as tools of destruction.

In the summer of 1950, an audit of wartime procurement expenses by the Egyptian government’s accounting bureau revealed what seemed like a shocking statistic — that only 25% of the budget designated for purchasing weapons had, in fact, been spent on them. Where had the rest of the money gone? Though a parliamentary inquiry stalled, Ihsan Abdel Quddous, a rising star in journalistic circles, vowed to find out.

Abdel Quddous would later become known as one of Egypt’s most popular and prolific novelists and screenwriters. In the late 1940s, however, his reputation rested primarily on political commentary. He was named editor-in-chief of the widely read weekly magazine Rose al-Yusuf in 1945, succeeding his mother, its founder. This was the platform from which he demanded that the truth behind the arms deals be publicly exposed. Beginning on June 6, 1950, Abdel Quddous published a series of withering editorials seeking to tether the purchases to the war’s devastating outcome. Rose al-Yusuf was renowned for its political cartoons, one of which accompanied Abdel Quddous’ June 6 editorial. It featured a wounded soldier with blood pooling at his feet and a caption that read: “Mustafa Marʿi [the leading parliamentary advocate for an investigation] said the Egyptian army’s bombs are wounding the ones who drop them; The martyr: ‘The sons of Israel didn’t kill me — my countrymen did!’” High-ranking members of the king’s entourage, Abdel Quddous’ argument went, were in cahoots with arms and munitions traders in Egypt and Europe. Eager to profit, they had funneled procurement funds to friends with criminally little regard for the quality of what was purchased. This was precisely the takeaway voiced in “Return My Heart” seven years later.

By Abdel Quddous’ own admission, the evidence he had in hand was fragmentary. He had pieces of peculiarly written contracts, knowledge of newly acquired fancy cars and indications of superfluous intermediaries, though he did not pretend to be able to connect the dots absent the formal inquiry he was pressing for. But the writer’s campaign was effective especially because he deftly deployed rumor to cement outrage toward the sitting regime. Abdel Quddous conveyed the impression that he was channeling the talk of the street, rather than seeking merely to influence it. By committing to the printed page whispers overheard in city streets and office hallways, he gave politicians the impression of someone closely attuned to public sentiment. He dangled lists of tidbits and half-truths as provocation, examples of what would threaten leaders’ grip if left unchecked. “It has been said,” he repeated over and over: “It has been said” that large sums of money had appeared in officials’ wives’ bank accounts, that old rifles had been salvaged from the sea and sent into battle, that depots near Rafah had gone up in smoke.

The affair did eventually wind up in court, with Egyptian media citing Abdel Quddous’ articles as the impetus for the prosecution of over a dozen officers and businesspeople. One trial took place under the monarchy, a second after the 1952 coup. But in the courtroom, the case fizzled, the punishment imposed amounting to little more than a scattering of fines. But Abdel Quddous’ visceral descriptions of common soldiers felled by their own guns had already captivated a much wider audience. The defective weapons had evolved into a shorthand indictment of an entire defective system. As time went on, the rumor’s migration from page to screen and into popular memory cemented in national discourse the moral dichotomy between the pre- and post-1952 regimes. The military came to be viewed as a blameless and competent alternative to the monarchy, rather than the party responsible for having lost a pivotal war.

Today, audiences watch “Return My Heart” with a mix of fondness and derision. One online viewer of the film last July 23 went as far as to exclaim, “We’ve been living a decadeslong illusion because of this film.” The defective weapons remain central to Egyptian memory of the 1948 war. But because of the link forged in Rose al-Yusuf and reinforced in films like “Return My Heart,” they are also bound to the founding narrative of the regime that came to power in 1952 — with the army at the center of politics, commerce and information. As the most visceral symbol of the wreckage that numbered the days of the old order, the defective weapons paved the way for the new one’s immaculate conception.