Listen to this story

Summer 1940. A young boy reads in his parents’ living room as a portrait of the French Gen. Charles de Gaulle watches over him from the mantelpiece. The house is not in Paris or Nice, but Alta Gracia, Argentina. And the young boy’s name is Ernesto Guevara.

Sixteen years later, Guevara would lead Cuba’s armed communist revolution. But at the time, “El Che” was a schoolboy in a small town in Argentina.

Guevara’s political consciousness came from his mother, Celia de la Serna. In the late 1930s — already married and with four children — de la Serna joined various anti-fascist groups and began to engage in left-wing activism. When war broke out in Europe, she helped resettle Spanish Republican refugees in Argentina. Then, when Hitler marched west in summer 1940, she turned her sights to France.

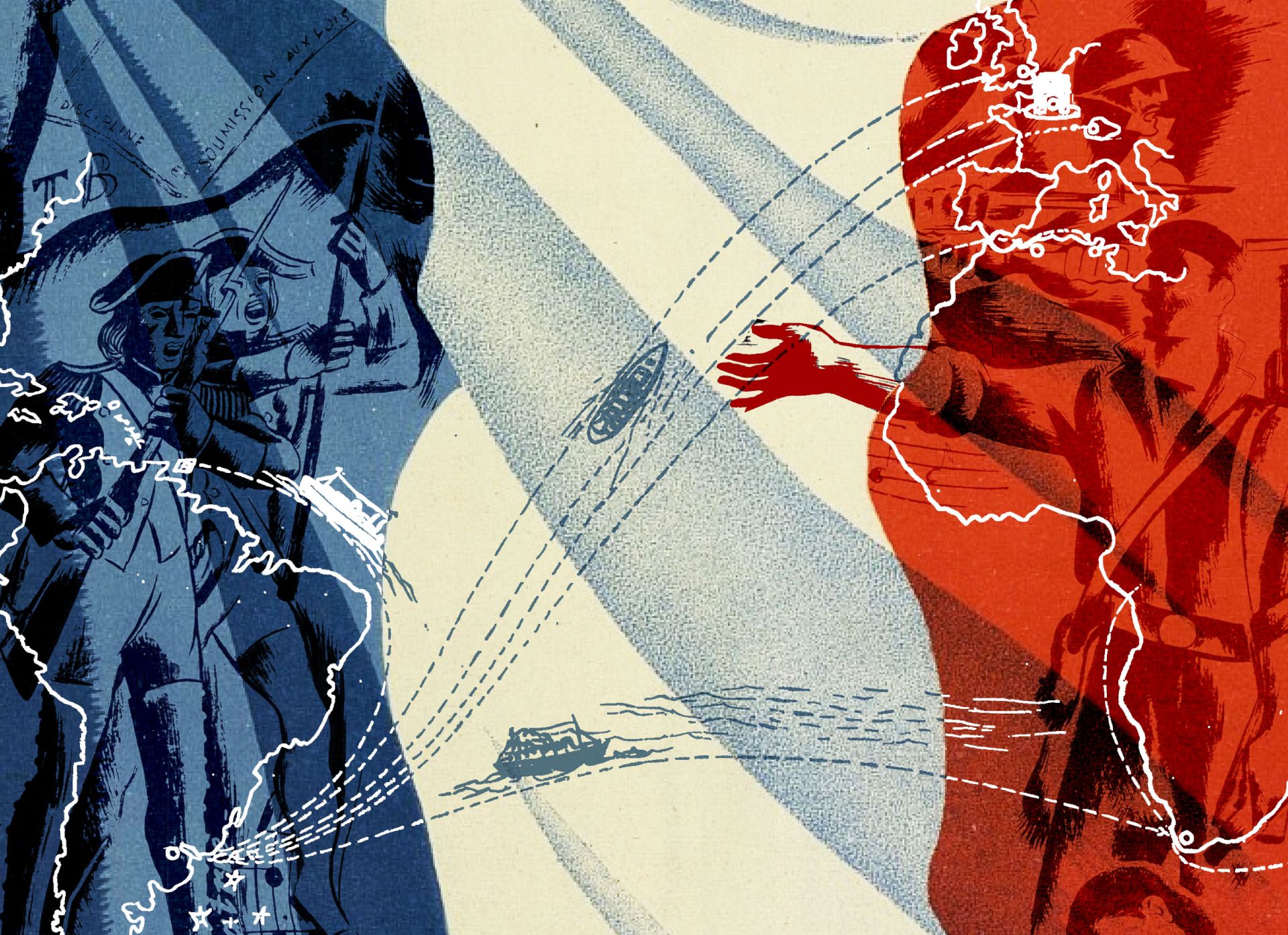

De la Serna must have listened to, or at least been aware of, de Gaulle’s speech on the BBC on June 18, 1940, in which he condemned the French armistice signed with the Nazis and called on the army to keep fighting. Around the world, French expatriates and Francophiles tuned in to this broadcast. The most active of them began to form external resistance committees. The constellation of these networks made up Free France, a state in exile that claimed to be the true incarnation of the fallen French Republic, with de Gaulle at its helm. Create a free account to continue reading Already a New Lines member? Log in here Create an account to access exclusive content.