It was set up to be a straightforward press conference announcing travel reforms for citizens living in East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR). On a November evening in 1989, local and foreign journalists gathered at the press center in the heart of East Berlin for the 6 p.m. briefing — seemingly unaware of the significance of what was about to unfold on this cold wintery night.

A sense of anger, desperation and a deep desire for change had been growing in the country over recent months as governments across the Eastern bloc started to ease border restrictions and allow greater freedom of movement. For the first time in decades, East Germans could envisage reuniting with their families in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), also known as West Germany, while many saw an opportunity for a different kind of future. The developments had been pushing protesters out onto East Germany’s streets and its leaders were under pressure to act.

As the clock ticked toward the next hour, things seemed to be going as planned for the GDR minister tasked with managing the media message, Guenter Schabowski. When asked about when travel reforms might take place, however, an unprepared Schabowski mistakenly answered that restrictions would be eased with immediate effect. The news electrified the room and spread fast outside of it. By the end of the night, thousands of East Berliners had gathered at the wall, confusing guards who eventually opened the gates. Huge crowds of West Berliners greeted them as they poured through, celebrating and crying. Soon, people from both sides took sledgehammers and chisels to the ultimate symbol of the Cold War. A month later, the GDR ceased to exist. Described in the German media as the “most beautiful mistake in history,” it led to the end of Germany’s division into two distinct parts following the end of World War II, and set the stage for the larger and economically stronger West Germany to try and build a bridge between the two entities that had been pitted against each other during the Cold War.

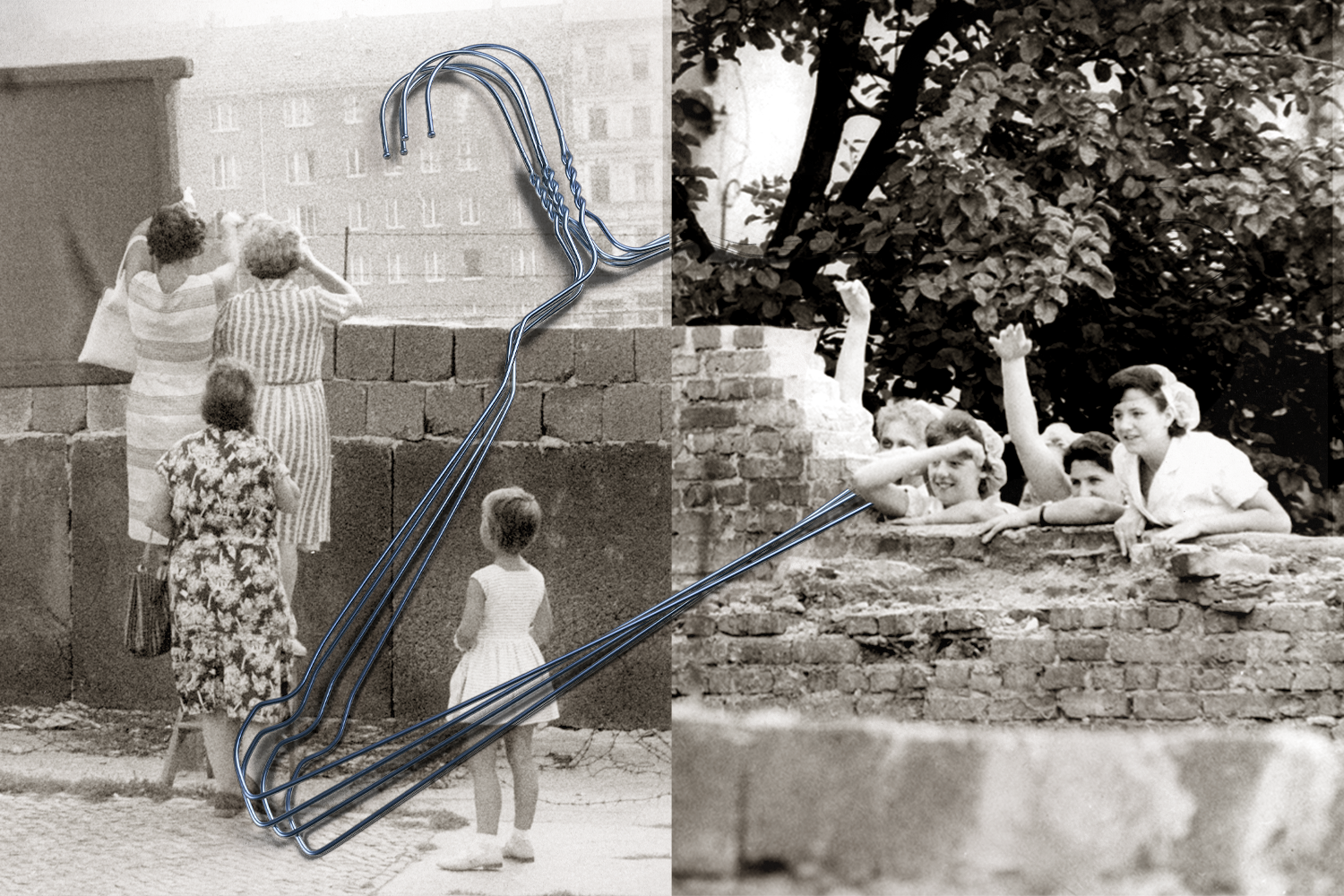

Much has since been written about German reunification — whether or not it worked out and which side benefited most. But one issue, that of reproductive rights, is often lacking in such reflections. In the West, abortion was illegal; in the East, it was decriminalized. The polarized positions spoke to the differing social values of the two states and were a central sticking point during reunification discussions, to the point that defining a new abortion law became a prerequisite for negotiations.

“Current debates are still characterized by the East-West divide,” says German historian Jessica Bock, who is currently a research assistant at the Digital German Women’s Archive, a state-funded initiative, explaining the influence of reunification on present-day discourse and abortion laws.

In Germany, a woman is broadly permitted to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy if she undergoes counseling and then waits at least three days to terminate. Yet outside of exceptions for medical reasons or rape, abortions are still technically illegal in the country and carry the weight of a three-year prison sentence. While women are rarely prosecuted, several doctors advertising the services in recent years have been handed hefty fines of thousands of dollars. State statistics show that there were 106,000 reported terminated pregnancies in Germany in 2023, a rise of 2.2% compared to the previous year. Women who go ahead with the procedure can face a costly, time-consuming process bound by bureaucracy, stigmatization and a lack of medical resources. The strict regulations have been criticized by abortion rights advocates who say the policies don’t meet international human rights standards.

With a smaller economy and population, the former GDR continues to be viewed by some of those living in the former West German states as less forward-thinking. But there were elements of its finely constructed constitution that stood out as being more progressive.

During the decades of partition, Germany developed two distinct cultures and political agendas. While East Germans drove around in their clunky “Trabi” cars, the other side favored Volkswagen Beetles and BMWs. As East Germans savored Vita Cola, Westerners sipped on Coca-Cola. And while style in East Germany was influenced by Moscow, those in the West wore luxury items and Levi’s jeans.

A further divide opened up in 1972, when East Germany revamped its abortion regulations in a majority vote in its parliament, or Volkskammer. Many East German women welcomed the new legislation that decriminalized the procedure and gave them the freedom to choose. A free service was permitted within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and procedures were also possible after the 12-week mark under certain conditions — if approved by a medical commission, for example, or if the woman’s life was at risk.

At the time, these were considered among the most progressive abortion laws in Europe because of how much power they granted women to decide whether to abort within the first 12 weeks. They stood out further because of comparisons with West Germany, where abortion was still illegal.

Among the most politically active women working on the issue in the GDR was Ulrike Busch, a professor and researcher who tells me that the decision fitted into a wider state-led push around reproductive and gender rights. “These regulations were unusually extensive for the time,” she explains. The decision to introduce them was justified with reference to the “‘equal rights of women in education and employment, marriage and family,’ and aimed at promoting these.” It was a key component of not just the GDR’s state agenda but standard policy across the Soviet bloc at the time.

Even before Germany’s division, abortion had long been an emotive issue in the country. It was illegal during the Weimar Republic from 1918 to 1933, a period when Finland and the Soviets began lifting restrictions. Then, under Nazi rule, the politics of abortion became intertwined with race. “Aryan” women were punished harshly for abortions, while others were not, and terminations were explicitly encouraged in cases of suspected disability or genetic disease.

Nazi propaganda images depicting the “volksgemeinschaft” or “people’s community” were common and showed pure Aryan families with blond-haired, strong parents, often with eagles fluttering in the background. Alicia Baier, an ob-gyn and co-founder and board member of Doctors for Choice, a nonprofit advocacy organization, grew up decades later in reunified western Germany. She tells New Lines that national socialism had an important effect on the issue because the Nazis had a very strong family and mother ideal they wanted to promote. “The role of the mother was to uphold racist ideas linked to a big German population and the Nazis shaped this picture of the mother who has to have as many children as possible, and has to be at home caring for the family.”

After Germany was defeated by the Allies, it was divided into four zones, with the American, British and French zones rapidly fusing into West Germany. The five states in East Germany were aligned with the Soviet Union and run as a socialist country within the Eastern bloc alongside Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Poland, among others. Berlin, geographically located in the GDR, was split in the same way.

Bock says that, by the 1970s, there was pressure on the GDR to move fast on abortion rights, with the Cold War and the battle between the two systems playing an important role. “There was a growing independent women’s rights movement in West Germany and the GDR wanted to prevent an independent women’s movement in their own state,” she explains. “This was an opportunity for the state to present itself as modern and with better emancipatory and gender equal laws.” Also important, she says, were concerns that East Germany was in danger of falling behind other countries in the Soviet bloc, like Poland and Yugoslavia, where abortion was legal. “Internally, it was part of wider reproductive regulations linked to maternity leave and childcare that encouraged and supported women both in the workforce and to help them grow the population.”

Other European countries had also taken steps to liberalize abortion laws, including France, Italy and the United Kingdom. It was a different picture in West Germany, where the procedure was illegal and broader reproductive rights legislation retained elements from both the Weimar Republic and the Nazi period that decreed abortion a highly punishable act.

Baier, who grew up in Heidelberg in western Germany after reunification, said that the influence of the church and the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) were very powerful. “The CDU blocked progressive steps several times from the 1970s onwards,” she says. While West Germany did approve legalization after the GDR, the decision was overturned by the country’s Federal Constitutional Court in 1975.

The strict regulations did, however, help spawn a strong feminist movement in the country, and opposition to the restrictions became part of public discourse. “Various initiatives were formed and they fought for women’s liberation and the right to self-determination,” says Bock.

Mirroring second-wave feminist movements that had been mobilized in the United States, women in West Germany were direct in their actions — they wanted change and weren’t afraid to call for it.

One nationwide campaign that was particularly effective came from Stern magazine in June 1971. Its headline shouted, “Wir haben abgetrieben!” (“We’ve had abortions!”), with the issue featuring the unheard and untold stories of more than 300 women, many of whom were high-profile figures such as actresses, whose pictures accompanied their stories.

Bock says the campaign broke taboos around a highly sensitive and emotive topic. “Before this, women didn’t talk about their abortion experiences but here they were, talking about the abortions they had in their kitchens and the risks to their health that they faced,” she says. By speaking out, women put themselves at risk of prison or losing their jobs, Bock says, explaining how the campaign encouraged women to talk about abortion and the discrimination they faced, also helping to mobilize women from a wider range of backgrounds.

Despite such efforts, there was little impact on the political status quo and, up until reunification in 1990, West Germany maintained its self-proclaimed duty to guarantee the protection of unborn life.

As the researchers Rachel Alsop and Jenny Hockey wrote in a 2001 article in the European Journal of Women’s Studies, at the time of reunification, “abortion was such a sensitive political issue, not only in terms of women’s reproductive rights, but also as a symbolic marker of the different social values between East and West, that the formulation of a new abortion law for the new united Germany became a precondition of the unification project.”

Busch, the abortion rights campaigner, was active at the time in both government-backed and grassroots-level initiatives. As a social scientist, she conducted research on the ground, gathered medical perspectives from doctors in the GDR, participated in panels on the issue and worked with the prominent family and sexual planning organization from West Germany, Pro Familia, which still exists today. She also played a key role in establishing the Berlin Family Planning Center.

Busch said that, after the Berlin Wall fell, it became clear relatively quickly that it would not be possible to harmonize two diametrically opposed legal and practical approaches to abortion, yet “East German politicians and the East German public did not want to give up the existing law.” Research from around this time looking at the differences in opinion between the two populations indicated that for East Germans, women’s employment played a significant role in determining opinions on abortion, while religious affiliation (in a country where atheism was encouraged) did not. In contrast, West Germans were largely unaffected by women’s employment status.

A compromise between the two was sought, while an attempt to legalize abortion in the unified German state was overturned by the Federal Constitutional Court in 1993, and only allowed with counseling and a three-day wait period. For East German women, it was a huge step backward. As Bock explains: “A woman from the GDR who terminated a pregnancy could now face up to three years in prison. Plus she had to ask for permission again. Adding to all of this at the time were more extreme political parties who followed the example of the so-called pro-life movement.”

There was no mass movement in the former GDR against these developments, Busch says, as East Germans faced many other huge changes, including job losses and institutional and company transitions while the country was absorbed into West Germany. “For many, the issue of abortion took a back seat and it was only important when it directly affected their own lives.”

What happened with abortion and reproductive rights reflected the wider picture in the wake of 1990. West Germany effectively took over the GDR and its structures and, nearly 35 years on, economic, political and social disparities — plus a dominance of West over East — persist across many aspects of German society.

As pressure has grown internally for Germany to pursue more progressive abortion legislation, there have been some small victories along the way. In 2022, a Nazi-era law that criminalized doctors for sharing information on abortion was overturned and, most recently, a law has been put in place that restricts anti-abortion protesters from approaching and harassing women at abortion and family planning centers. Politicians are facing further calls for change after a government-appointed commission earlier this year called for abortions to become legal within the first 12 weeks.

It is difficult to understand current legislation without seeing it in the context of Germany’s complex history, and those working to extend abortion rights say that the public conversation still contains gaps in knowledge that limit criticism of past policies. While the GDR had greater abortion rights than the FRG, there were issues with how well medical practitioners were able to handle the increase in women seeking terminations. And while white East German women were granted full reproductive rights, women from parts of Africa, Vietnam and other politically aligned nations who had come to work in the GDR had to choose between two options if they became pregnant. “One option was abortion and the second option was to go back to their home country,” Bock says. “So when you talk about abortion rights in the GDR, you have to focus on race as well as gender.”

Even today, in mainstream public and political discourse, immigration and abortion are being tied together — there is still some way to go to break down what Germans call “die Mauer in den Koepfen” — the wall in the mind. Discord is still easily stirred, as seen by surging support for the far-right political party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which receives the vast majority of its support in the states that made up East Germany. The party is keen on tighter abortion laws as a complement to curbing immigration, harking back to Nazi-era policies that many in Germany believed were firmly in the past. But as EU elections this summer showed, even young people are now among their supporters.

Bock concludes that for Germany to move forward, the country needs to learn the lessons from its divided past. “It’s very important for us to know about this history because we need to know what the generation before us experienced, and for us to avoid the same mistakes and build better policies that are not based on ideology.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.