Listen to this story

Sometime in 1851, a local chess player in a pastoral hamlet outside Calcutta in pre-independence India chose, as his first move in the game, to move his black pawn just one square forward, instead of two.

This was “faulty style,” according to the British players of the time, since pawns are allowed to begin with a double-step. Yet, over 170 years later, when the 16-year-old Indian grandmaster Dommaraju Gukesh (better known as “Gukesh D”) played the very same opening against the Italian-American grandmaster Fabiano Caruana at the 2022 Chess Olympiad in India, the teenager won his eighth consecutive game, defeating the higher-rated Caruana with an opening sequence of moves known today as the “King’s Indian.”

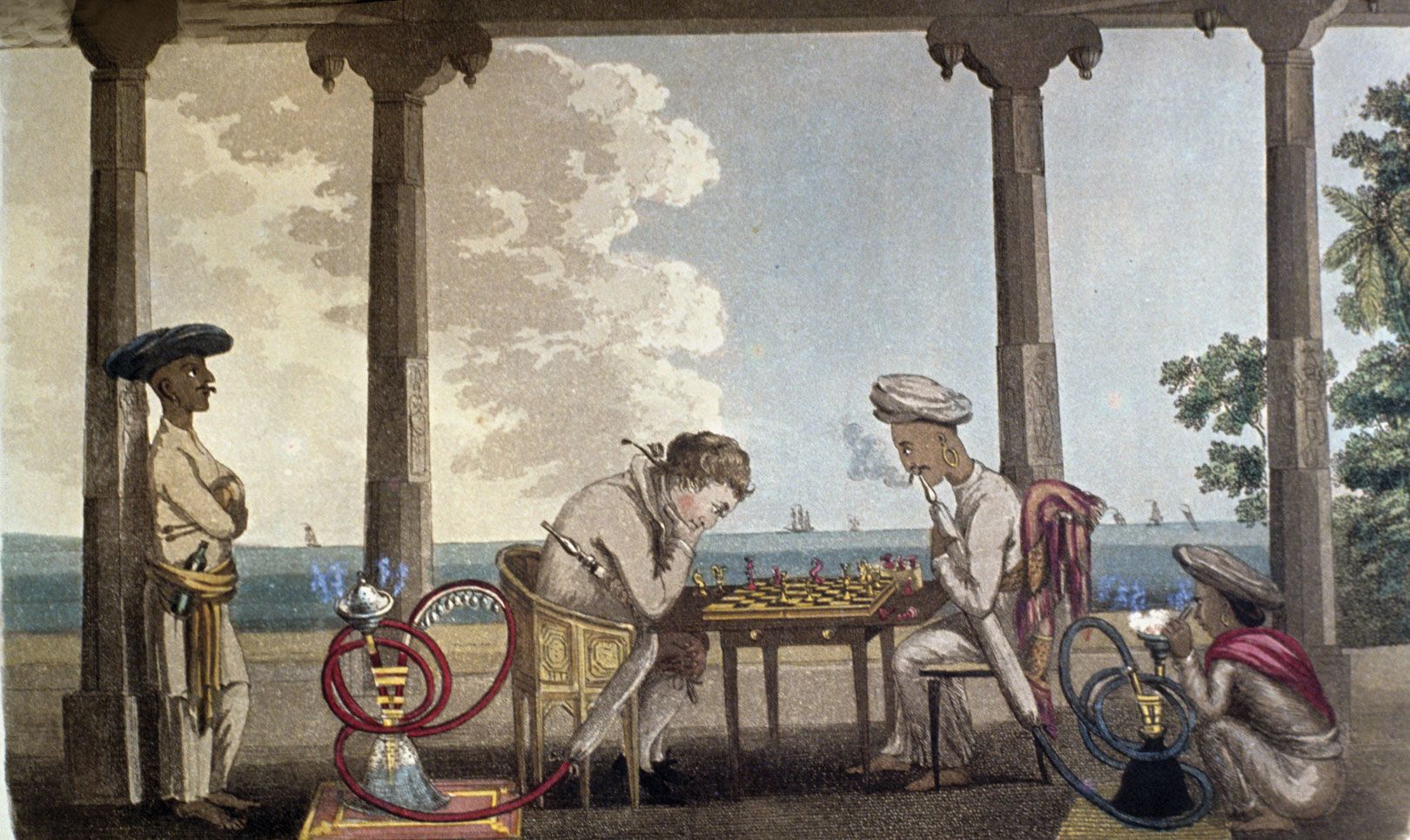

Contained within this period of nearly two centuries is a fascinating but forgotten story of how this so-called “Indian” opening got its name. The story begins with a distinguished British chess player, practicing as a barrister in 1840s Calcutta, desperate to be challenged by a strong player in India. A colleague informed him that a “Brahmin in the mofussil (province) of Calcutta” was unbeaten on his turf. Thus began a rivalry at the Calcutta Chess Club from 1848 to 1860 that would — though none knew it at the time — end up bequeathing a formidable arsenal of “Indian” defenses to the world of chess. Create a free account to continue reading Already a New Lines member? Log in here Create an account to access exclusive content.