During our morning chitchats on the terrace of our house, my father would often recount the details of a singularly memorable event. He was about 10 when he saw the first president of the Republic of Egypt, Muhammad Naguib, who came to power after the overthrow of King Farouk in 1952, disembark from his ship to spend a few minutes in Dahmit, our small but significant village in Egypt’s Nubian region in the far south of the country. The president gave the villagers a speech in Kenzi, one of the main two languages spoken by Nubians in Egypt and neighboring Sudan, a tongue that was never spoken again in public by any other senior Egyptian official.

My father was born in Dahmit after 1933, following the second heightening of the Aswan Low Dam, built decades before the more celebrated High Dam. Dahmit, like many other Nubian villages, underwent significant changes because of the initial construction of the dam and its reservoir in 1902 as well as their subsequent raisings in 1912 and 1933, which led to higher water levels in the region. Located on the banks of the Nile, Dahmit was one of the Nubian villages directly affected by the rising water. Large tracts of land and houses in the village were submerged, forcing residents to relocate to higher and safer areas while receiving only minimal and delayed support from the British colonial authorities and the Egyptian monarchy. The conditions that Dahmit and neighboring Nubian villages endured made the rare visit from the Egyptian president a hugely evocative memory for my father.

As the waters rose, many of Dahmit’s inhabitants were forced to leave their homes and move to other areas in search of land and alternative housing, disrupting the village’s social fabric and leading to the dispersion of families. Following the displacement, efforts to build homes and infrastructure in new locations began, but the quality and speed of reconstruction were hampered by a lack of resources.

Despite the challenges faced by the village after 1933, the residents managed to preserve their Nubian heritage through traditional songs, dances, the Nubian languages and other cultural practices, reflecting the strong social and cultural cohesion of Dahmit’s people.

This context adds another layer to the importance of Muhammad Naguib’s visit and speech, as Dahmit, like other Nubian villages, suffered from repeated marginalization and forced displacement.

The Nubian community had been marginalized even before 1902. Their suffering intensified, however, with the state projects and forced displacements that began in that year with the construction of the Aswan reservoir, which marked the beginning of a series of displacements uprooting Nubians from their ancestral lands. These repeated displacements, which culminated with the building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, submerged vast areas and forced thousands of Nubians to relocate to less fertile lands, far from their historic homes and in disconnected locations. Waves of migration to Cairo, Alexandria and the Suez Canal region, and later to Gulf countries, further fractured Nubian families and restructured their communities, diluting their cultural cohesion. The disruption severed Nubians’ deep connections to their homeland and communities, resulting in significant hardship. Kenzi, considered a threatened language, along with other Nubian languages, has also faced ongoing challenges because it is not officially recognized, taught or conserved by the state. This neglect has silenced Nubian voices for decades, contributing to the erosion of their cultural identity and leaving the community disenfranchised and marginalized within Egyptian society.

When he first told me about Naguib’s visit, I asked my father with great astonishment, “Could Muhammad Naguib speak Nubian?” referring to Kenzi, the Nubian language spoken around our village.

He replied, “No, but it seems that someone wrote it for him in Arabic or English letters as he was reading from a paper and never uttered any Nubian word outside the written text.”

My next question was about what he could remember from the speech. He recalled only one sentence: “I go elrgogodo nesb ery,” which means “I have lineage with you,” a phrase meant to express kinship that has stuck in my father’s mind for decades.

Over the next few months, I began in earnest an attempt to determine the truth behind the story of Naguib’s oratory. The question of whether Egypt’s first president delivered a speech in a language that is now endangered and belongs to a community that has been historically marginalized is more than purely symbolic. It goes to the heart of questions of identity that have long plagued Nubia, torn between its roots, its rich culture and heritage, and its place in the grander Egyptian nationalist project.

Born in Khartoum in 1901, Naguib rose through the military ranks to become a general in the Egyptian army. He played a pivotal role in organizing and coordinating the army’s actions that ended the reign of the royal family — descendants of the legendary Muhammed Ali Pasha. Subsequently, he was chosen as the chair of the Revolutionary Command Council and then as president of the republic.

Despite his popularity, Naguib was removed from office and placed under house arrest in 1954 because of disagreements with other members of the Revolutionary Command Council, particularly Gamal Abdel Nasser, over Egypt’s future governance and the direction of the revolution. Naguib later wrote in his memoir, “I Was a President of Egypt,” that the disagreement arose after he voiced his support for returning the army to its barracks and handing power to civilians. The testimonies of other council members didn’t support that claim.

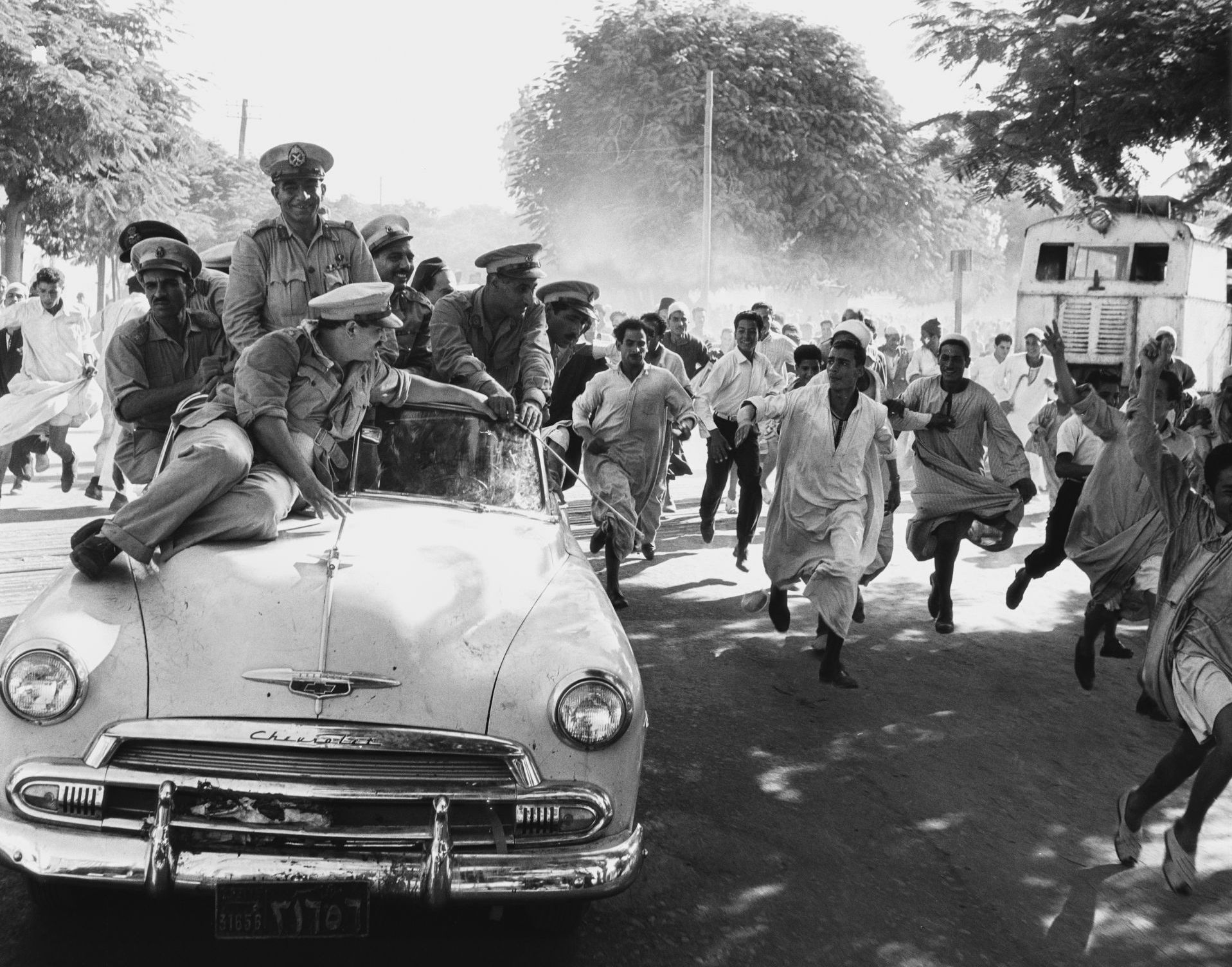

Naguib’s visit to Dahmit in 1953 was part of a tour of southern Egypt aimed at strengthening the ties between the new political leadership and the people, following the king’s overthrow. The visit was a strategic effort to bolster his and the army’s popularity and ensure the support of the Nubian community for its role and initiatives.

Egypt’s president delivering a speech in a Nubian language during his visit to Dahmit would have been highly significant. It would have demonstrated respect for and recognition of the Nubian people and their rich culture. Additionally, such a speech would have helped to promote the Nubian languages, strengthening the relationship between the government and the Nubian community. This act would have emphasized the inclusiveness of the new political leadership and acknowledged the historical and cultural contributions of the Nubian people to Egypt’s heritage, an acknowledgment that was particularly important after years of neglect and the uncoordinated displacement of Nubian communities due to the development of the reservoir at Aswan.

Over the last three years of my visits to my village, Dahmit, I discussed this subject numerous times with my father, and his testimony remained consistent. During those years, I considered researching the issue to try to find solid proof of the speech, in order to make the public aware of it. I finally began by investigating sources of oral history and newspaper archives. I wanted to uncover more details about Naguib’s speech, particularly its context, and its effect on the Nubian community and Egyptian society at the time, hopefully highlighting an overlooked aspect of Egypt’s revolutionary history.

I started my journey from my village by contacting our village historian, Mubarak Othman Labib, and asking him about his knowledge of Naguib’s visit to Dahmit. He told me that Nubian historical sources documented Naguib’s visit to Abu-Hor (another Nubian village) in pictures and newspaper articles. Still, there is no documentation of his visit to Dahmit, for it was a quick stop on his way to Abu-Hor.

Labib also provided me with some pages of a book called “Abu-Hor Baladna,” written by Abu Bakr Mahjoub Hassan (a Nubian researcher and archivist) and published by the Nubian Studies and Documentation Center. The book chronicles Naguib’s Abu-Hor visit and his speech to the mayors of the Kunuz villages (Daboud, Dahmit, Amberkab, Kushtamna, al-Dakkah, Kalabsha).

My search of Nubian websites, pages and blogs didn’t indicate that the president stopped at or came ashore in Dahmit. I reached out to my father again and the following conversation occurred: “Hajj … President Muhammad Naguib didn’t go to Dahmit; he only went to Abu-Hor and met with the mayors there. Maybe he only waved to you from the boat, but you’ve forgotten?”

“No, he came ashore in Dahmit. He went to many villages and spoke in Dahmit in Nubian,” he insisted.

I then began researching official sources. Although I could not obtain information from the press archives available on the internet, Naguib’s website within the Bibliotheca Alexandrina’s documentation projects allowed me to explore many aspects of that visit.

Within the site’s archival material is a report published in Al-Ahram on Nov. 7, 1953, outlining the dates, program and locations of the president’s tour in the south. He arrived in Aswan on Nov. 17, 1953, and inaugurated several projects in the city, after which he sailed the Nile to Nubia.

The report made it clear that the president would visit the villages of Onaiba, Tomar, al-Dur, Abu-Simbel, Abrim, al-Dakkah, al-Maliki and Balana to inaugurate some projects. It said that he would then visit the shores of some villages to meet with the people in Dahmit, Abu-Hor, al-Sayyala, al-Allaqi, Toshka and Adendan.

It was now clear, per the official program, that the president had landed in Dahmit and met with the people there.

Another piece of evidence was a photo posted on the Facebook page of Nubian Geographic, an initiative meant to document Nubian history, culture and geography, claiming to represent the people at the village of Abu-Hor receiving President Naguib.

Although the photo is said to be from the village of Abu-Hor, the women are not wearing the traditional shugga (a white wrap worn over black clothing by married women in some of the Kenouz villages, which is purely white without any color interweaving or patterns). Instead, they are dressed in black garments similar to those worn by the women of Dahmit village, which led me to believe that the photo had been misattributed and was in fact from my village.

In Dahmit and Dabod, the villages of northern Nubia, married women used to wear black or colorful clothing, while in Abu-Hor, Kalabsha, Qurta, Alaqi and al-Dakkah — other Kenouz villages — married women would wear the white wrap over black clothing to distinguish between married and unmarried women. This attire was an essential part of the bride’s preparation. Although this tradition has somewhat diminished nowadays, it still exists in Kenouz villages.

Another piece of evidence came from the book “The Truth About the July Revolution,” published by the Family Library in 2002, in which Abdul Mohsen Abu al-Nour, commander of the Republican Guard at the time and one of Naguib’s companions during that trip, clearly refers to his use of a Nubian language.

“One of the stories that I remember is that he wanted to get closer to the people of Nubia, and we had a Nubian officer called Yaqoub Hassan Ahmed,” Abu al-Nour recounted. “So, Naguib asked him to prepare a speech for him in Nubian. And since Naguib was unfamiliar with Nubian, he asked the officer to write the speech in Arabic letters. When the ship docked in the first village of Nubia, he took off his cap, which contained the speech, and stood in front of a microphone on the deck reciting the speech in Nubian.”

However, an important question remains as to whether this speech exists in the National Archives or not. I tried to find the texts or recordings of the president’s speeches during his trip to Nubia in collaboration with other researchers. Still, in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina’s electronic archive we only found the text of his speeches in Mashrou al-Dikkah and Onaiba, dated Nov. 21, 1953. That was not the speech my father was referring to.

According to the archival document, “The ship Sudan, with President and Staff Major General Muhammad Naguib on board, arrived ashore at half past eight to the area of Al-Dakkah project, where the president was received with the greatest manifestations of hospitality and honor by the notables, mayors, parents and students of preparatory schools from the towns of Qersha, Jarf Hussein, Kushtmnah East, Kushtmnah West, Al-Dakkah, Al-Allaqi, and Qurta.”

Still, based on the testimony of my father, and confirmation from media outlets as well as the testimony of the commander of the Republican Guard who accompanied him during the visit, we can conclude that Naguib landed in Dahmit and spoke in Kenzi.

What keeps hope alive about the existence of some recording or other unpublished documents related to that visit, is a reference by the Republican Guard commander Abu al-Nour in his book to an accompanying media delegation that recorded the meetings and speeches to be archived at the Ministry of Guidance (a ministry overlooking culture and broadcast media at the time), which did not broadcast them in full.

Since that extraordinary event, and for nearly 70 years, my father has not heard any other president speaking in Kenzi. None of the generations of Nubians since have heard any president speaking in their language, and this event has yet to receive the research it deserves. This attempt may open the door to searching for the presidency’s audio archive and the Egyptian radio archives to access any audio materials preserved from this tour.

Perhaps my father and his generation will once more hear the voice of the president giving his speech in Kenzi, and we and future generations may hear it for the first time.

The search for the event, stuck in my father’s memory but erased from national memory, continues.

An earlier version of this article was published in Arabic on Almanassa, an independent e-journalism website. The translation was funded by the Nubian Narrating Nubia project at the University of Michigan Humanities Collaboratory.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.