Russia and the West are now at war. And the delicate dance leading to conflict between nuclear powers is a form of poker, not chess. Putin is used to bluffing and stealing the pot. He was shocked that the West called his biggest raise ever. Now what happens? Game theory and the poker concept of “pot odds” point to more escalations. I argue that these can possibly be averted through eschewing negotiations and focusing on deterrence.

Nuclear powers generally don’t bumble into war against each other. And make no mistake, since Feb. 24, NATO is for all intents and purposes at war with Putin’s Russia. True, this is partially a limited war, in that NATO militaries will not directly engage unless NATO territory is attacked, but it is also an unlimited war in that no financial or military options are off the table and Putin’s regime is existentially threatened in the way that it has not been in previous conflicts in Georgia, Syria or the Donbas.

I account for this surprising outcome because of a series of miscalculations by both sides. I assert that neither Putin, Biden, Zelenskyy, Macron nor Scholz wanted it to come to this. All wanted to avoid this outcome, which is suboptimal for all of their interests. Yet, having reached this point, all actors will likely be trapped into yet further escalations in the days to come. The only way to stop this cycle of escalations is for Western leaders to pivot from negotiations to deterrence. To better understand this paradoxical state of affairs, I believe we should explore various gaming metaphors to better conceptualize the current crisis and the realm of options open to our policymakers.

Vladimir Putin is clearly an accomplished sportsman and an intuitive poker player. As a judo master, he has decades of training in probing for an opponent’s weakness and then stealthily exploiting it while going for a knockout blow. As a seasoned practitioner of the poker-like aspects of diplomacy and counterinsurgency, he has been consistently calling America’s bluffs for several U.S. presidential administrations already. Over these decades, he has received repeated confirmations that brinkmanship pays and no major indications that his preferred strategy would all of a sudden fail.

Buoyed by his previous successes, Putin thought he could read Biden’s tells even over Zoom. Filled with dreams of future grandeur and calculations of his waning hard power, he wanted to steal one more big pot before it was too late. Putin has also grasped that by being an unpredictable bully he is better able to cow adversaries. Game theory tells us that wild aggression verging on, or feigning, psychopathy can grant a poker player a key edge against more “circumspect” actors. In the game theorist’s version of chicken, a rational actor impersonating a megalomaniac psychopath rates to win against a selfless, reflective, rules-based actor. In high-stakes gambling, even if played adroitly, the hothead approach will frequently experience a greater expected value (EV), but when it fails, the results can be disastrous. This is why it is called gambling after all.

Like many gambling games, diplomacy is an iterative contest in which players mold their strategies progressively in response to adversaries’ feedbacks and their analysis of other players’ preferences and risk thresholds. Putin has correctly understood that Western leaderships and populaces are “war-weary” as a result of the fiascos in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has been accurately reading this as at the root of our default “appeasement responses” to piecemeal acts of Russian aggression. This has spurred him to push progressively further and increasingly inhabit the hot-head approach to his gameplay. The lack of an overwhelming Western pushback against his unprovoked aggression in Georgia in 2008 encouraged him to annex the Crimea in 2014. Obama’s lack of enforcement of “the red line” over Syrian chemical weapons use in 2012-13 convinced Putin that he could deploy mercenaries, barrel bombs and indiscriminate shelling to keep Assad in power and get away with it. He was proved right.

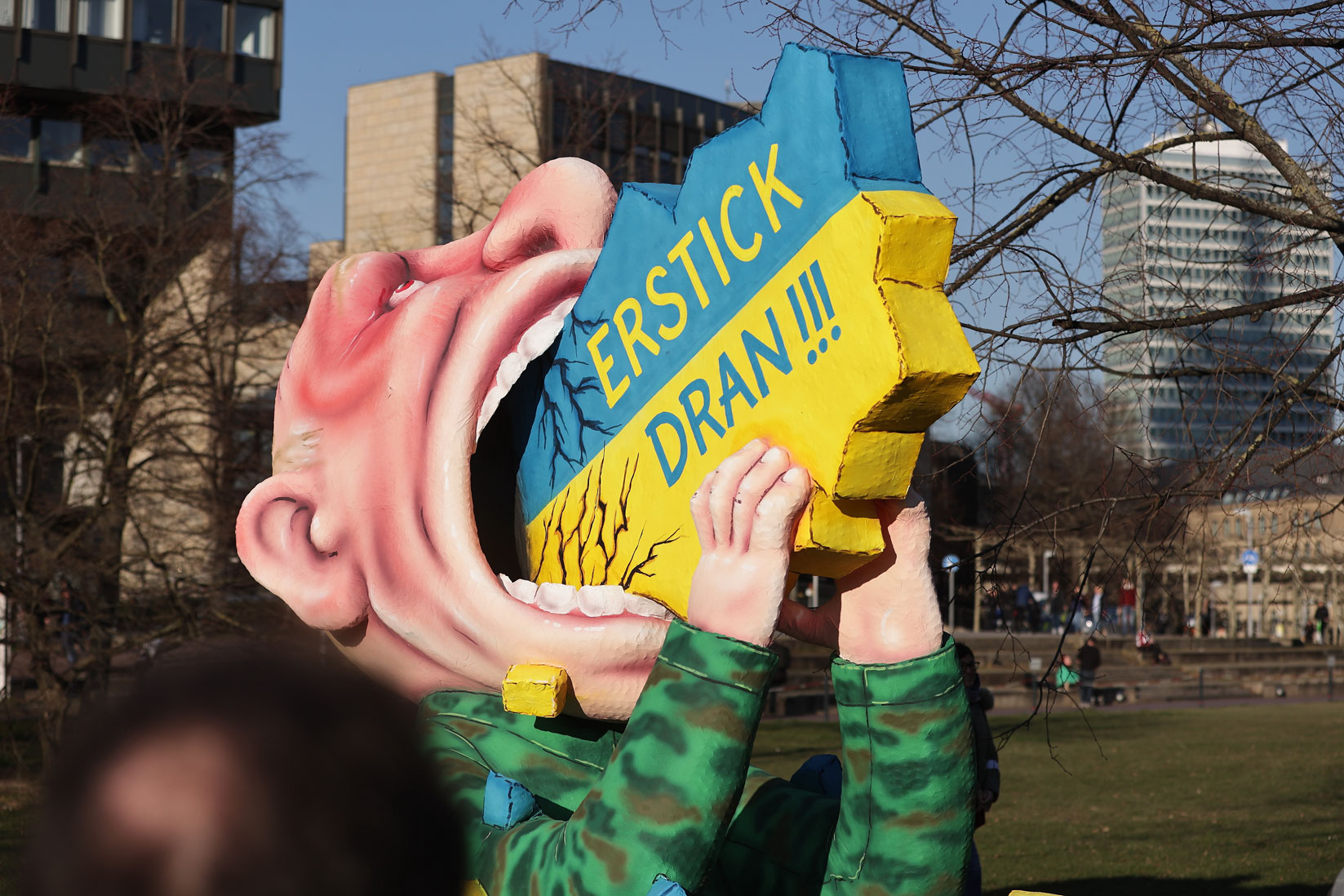

Reflecting on this decade’s long trend line of Western appeasement, war weariness and passivity, he felt that the moment for more decisive action may have arisen. The intertwined phenomena of Trump and Brexit were seen in the Kremlin as wins that had weakened the West’s internal cohesion and might even have been meaningfully aided by Russian information operations. Finally, an unproven German leader had recently taken over the chancellery and there were noises in both Downing Street and the White House of a dramatic pivot away from Europe toward Asia, seeking to contain an ascendant China. He also noted that the spot price for European natural gas was soaring in late 2021 and that EU domestic gas production has declined and now covers only 42% of consumption, as compared with 53% in 2010.

Assimilating these various inputs, Putin probed for further Western weaknesses by progressively massing troops around Ukraine. Sensing a lack of concrete responses to counterbalance his troop movements and aware that the Ukrainian army was progressively gaining strength as it integrated Western military support, he decided that the optimal moment had arisen for a decisive invasion. It was now or never. He decided to cross the Rubicon, or shall we say, the Dnieper.

Even the most seasoned poker players sometimes miscalculate. Even a lifelong judo master sometimes attacks too brazenly, leaving himself open to counterattack. This can happen as a result of both sides misreading the strategic context. Sometimes the pigeon (as novices are called in backgammon) misplays the position in such a way that leads to the expert overcompensating and finding himself subsequently trapped in a variation that incentivizes yet further suboptimal plays.

Russia is now not only in a hot war with the majority of the Ukrainian people (including most of the native Russian speakers) but in an all-out proxy and financial war with a united Western alliance made up of all NATO countries and most democracies on earth. The world is more united against Russia than even during the height of the Cold War.

Putin has definitely blundered. Nonetheless, this does not mean that Putin has all of sudden become unhinged or is losing his mind or is having a genuine psychotic episode, as various pundits are asserting. This outcome is the predictable result of the strategies that Putin has been deploying for the past two decades. Playing aggressive brinkmanship diplomacy closely resembles high-stakes poker in that it requires one to take big gambles based on imperfect information and iterative interactions with a familiar adversary. Faced with such circumstances, even the world’s best gamblers sometimes overplay their hands and go bust. Diplomacy, like gambling, involves profound elements of risk and chance.

Before I draw on my personal experience as a semiprofessional gambler to investigate specific gaming metaphors to model the assumptions and miscalculations that can shed light on how we got to the current moment in Ukraine, I think it is useful to take a step back and quickly examine various scholarly and media narratives about diplomacy.

Diplomacy, and especially warfare, is sometimes compared to chess. I think this is largely inappropriate as it implies that there is a “correct/winning” move and that other moves are wrong or suboptimal. Chess analogies also imply that one is playing the position and not the opponent. In chess, the best move is the optimal move independent of who one is playing and what her/his tendencies are. In the late 1990s, IBM’s chess playing artificial intelligence known as Deep Blue beat chess world champion Garry Kasparov not by anticipating Kasparov’s tendencies and countering them but rather by playing perfect moves. Therefore, I think we can simply discard the chess analogy altogether as entirely contrived. Diplomacy is not chess; the right move does not always win and even more frequently the wrong move does not lose.

Daniel Baer recently wrote an essay for Foreign Policy, titled “Why the Chess Metaphor for Putin Is Wrong: The problem with Russia is not a game,” in which he argued that because Putin is a psychopathic thug, the present conflict is more serious than a game of chess. Baer also argued that Putin is simply flouting the rules of the game of diplomatic “chess,” while our rational Western leaders play adeptly to contain him within acceptable diplomatic rules. Similarly, retired CIA senior clandestine services officer Dan Hoffman told Fox News, “The profile of Vladimir Putin from today is not the one that we would have written two weeks ago, or two years ago. So it’s almost like we’ve seen a transition from a chess player to a poker player.”

I am asserting something quite different from Baer and Hoffman. Putin has always been playing poker, because diplomacy is always poker and never chess and Putin understands this even if various democratic leaders do not. I think diplomacy and business contain elements of imperfect information that favor bluffs and incentivize bold and unpredictable aggression. As such the diplomatic and business arenas are inherently not similar to chess but do resemble other games. Napoleon or Hitler’s increasing preference for unpredictable and bold aggression over time was promoted by the very nature of the international system, but then when they overplayed their hands it was their own undoing. Contrary to Baer, I think it would be laudable if democratic leaders learned to be a bit wilder and savvier with their threats. Not in a clownish Trumpian way, but more in line with true game theory approaches.

There are other misleading metaphors out there. I think it is essential that we debunk the range of myths behind the Realist International Relations (Realist IR) school that posits that nation-states maximize their interests, analogously to the way that classical prebehavioral economics models see individuals in a free market as utility-maximizing. Neither model reflects reality.

CEOs do not always make decisions to increase either long-term shareholder value or quarterly returns, while politicians don’t always enact policies that concretely maximize their nation’s short-term or long-term interests. Humans are not machines. Businessmen don’t inherently make decisions to maximize equity and negotiators don’t usually achieve optimal outcomes with their deals.

Business leaders and politicians are frequently far more concerned with their own egos, how they are perceived and about staying in their current position of power than about achieving some abstract version of profit or interest maximization. In my recent book, “Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder,” I seek to correct Realist IR theory. I introduce the concepts of decision-maker psychology and the preference of incumbents for the status quo as correctives to IR theory akin to those that behavioral economists introduced to classical economics more than 30 years ago.

If chess and classical models of free market economic competition are not good models of diplomacy or warfare, then what is? Gambling games. Diplomacy and war contain a healthy degree of chance. This is why for time immemorial they have been modeled by different features of the classical gambling games that contain degrees of strategy, chance, skill, opponent psychological considerations and imperfect information. It is tragic that they are not taught to diplomats and taken seriously in political science departments.

Poker, in particular, and other games of imperfect information involve an iterative element of making certain moves to feel out your adversary’s response and then waiting for an opportunity to capitalize on perceived opponent tendencies. Bridge introduces the element of trying to optimally coordinate with your allies amid imperfect information and limited signaling capacity. Backgammon introduces the elements of timing, pursuing multiple game plans simultaneously and being able to play to win even when in a seemingly hopeless position.

As a former world champion of doubles backgammon who can afford to translate my book into Arabic and hire a publicist only due to my performance in high-stakes cash games, I see Putin as a traditionally successful game player who has fallen into a trap of his own making. For me, he is a strong and intuitive player who has been gradually molding his game to become more brazen to capitalize on his opponent’s perceived weaknesses (i.e. appeasement and poor internal coordination). This is how many street hustlers and professional gamblers mold their backgammon play over time. They gradually adopt a very aggressive style seeking to push around their hobbyist opponents, intimidating them with big cubes (the backgammon equivalent of poker’s “raise”) and flashy moves.

Having learned and largely mastered this style of play, Putin then pushed too far, causing an opponent whose tendency was to appease and coordinate poorly to become affronted and, all of a sudden, wish to stand resolute and to share information proactively. This happens frequently in gaming as opponents are constantly compensating for their own previous missteps. In high-stakes cash backgammon, if I always played the “bot” move (i.e. the move that the most advanced neural net backgammon computer program says garners the most equity against a perfect opponent response), I would miss out on a lot of my human advantage against weaker opponents.

A professional hustler derives an edge in a high-stakes chouette (as multiplayer backgammon is called) by understanding each opponent’s tendencies and gauging their current state of mind, for example a propensity by a weaker, wealthier and more emotional player to “steam” when behind on the score sheet. When faced with this kind of opponent, a shark changes his cube action: cubing later, hoping to elicit wrong takes from the steaming opponent, who sees his position on the score sheet and the time-delimited nature of the chouette and wishes to get back his losses all in one game. (For the uninitiated, steaming is the backgammon equivalent of what in poker is called “going on tilt.” It is the loss of emotional balance in a gambling context usually causing the “steamed” player to play more carelessly.)

Many times I have cubed late against a steaming pigeon and provoked a bad take in a nearly hopeless position. Yet, other times seeking to delay my cube, I have lost my market by not cubing at the proper moment. In this case, my opponent’s position has deteriorated to a point that even a steaming pigeon cannot envision that he has the requisite winning chances and knows he must pass.

However, Putin doesn’t read the West as a steaming pigeon. He reads us as the opposite, as a tight fish who luckily finds himself ahead on the score sheet toward the end of a long session. This backgammon analogy captures many aspects of where we truly are. Imagine there is only an hour left in the chouette, and the West is ahead on the score sheet (i.e. we are the incumbent super power in the world order). In each game in which Putin cultivates an advantage, he has been giving pushy cubes, which the West has hemmed and hawed over before eventually passing (this is our complaining about Russian aggression but eventually adopting appeasement with regard to Georgia, Syria, Crimea and the influence operations concerning the 2016 election). Emboldened by our tendency to pass while ahead, this time Putin cubes us so early that it is very difficult for us to rationally see the position as a pass. The more we investigate the position, it dawns on us that Putin’s previous series of cubes were likely not proper doubles and if we had taken those cubes (rather than dropping), we would have had a very reasonable chance of winning. In fact, so outraged by this current cube, the deeper we look at this position, we think that we could be the favorites and that Putin’s cube is pure insolence. With our pride finally piqued, we regret our previous series of passes, so we decide to beaver! (A beaver in backgammon is when the party being cubed thinks that the cube is highly inaccurate and that the party being doubled is actually an equity favorite, so he chooses to take at four times the previous stake rather than two times.) Fed up with the incremental costs of appeasement and grasping the extreme geostrategic importance of Ukraine and the absurd suffering of a proud and independent people, we have finally decided to draw a line in the sand and to profoundly raise the stakes of the current interaction.

More apt than even this backgammon model, which captures certain key elements, let’s consider the current confrontation as a heads-up poker game. Frequently, the professional player has greater psychological and technological insights but a smaller bankroll and greater need to win at all costs than his hobbyist adversary. In our instance, the West has vastly more chips than Putin but is less adept at internal coordination (which could be modeled as multi-move look-ahead, like a chess player who can see several moves ahead), eschews brinkmanship (which could be conceived as engaging in our own bluffing or compensation to opponent’s tendencies) and loves negotiations (which are perceived as weakness).

If we look at Putin as trying to play a weak hand with a minimal stack of chips to best effect, certain dynamics of the current crisis come into focus. Let us consider the recent chain of events from this perspective. For over 60 years, exploiting Western media freedom, partisan divides and the profit motive has been a standard feature of Russian influence operations and active measures. Russia has progressively honed a specific doctrine or game-playing style in response to Western countermeasures. In recent years, it has found that the internet and globalization make disruptive actions inside an opponent’s territory a lot easier. Our era of enduring disorder is characterized by a diffusion of power centers in the free world and conversely, their consolidation in the authoritarian world.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, ExxonMobil, BP, McKinsey, PWC and Deutsche Bank have all undermined the policy objectives of the U.S., U.K. and German governments toward Russia, while nominally independent corporations Gazprom, Rosneft and the Wagner Group allow Putin to influence geopolitical outcomes that official Russian state institutions could not sway.

Of course, there is no disputing that the West’s overall stack of military and financial resources is more than 10 times greater than Russia’s, yet Putin can choose when to play all of Russia’s cyber, military and gas cards at any time of his choosing, while American presidents cannot necessarily always incentivize the Poles, Turks and Germans to coordinate their approaches to military deterrence, nor can he necessarily block ExxonMobil or Deutsche Bank from underwriting the Russian economy.

So, despite our strong fundamentals, Putin correctly assessed that the West’s internal discord weakens our hand. It seems, however, that he didn’t fully appreciate that an overly bold play on his part might galvanize greater coordination capacity among the West’s various component states, corporations and populaces. These dynamics are key features of what I term the Global Enduring Disorder, an era in which the old certitudes of American hegemonic leadership have been replaced by coordination complexities among the Western allies and a desire by key players like Russia to promote disorder rather than an alternative order. Putin banked on his escalation as deepening the dynamics of the disorder, failing to grasp that a minor escalation would have promoted divergent responses while a major escalation would incentivize collaboration.

Given all of what Putin knows about our tendencies, he perceived the Afghan withdrawal as a sign of weakness and poor coordination among NATO allies, so he waited for European demand for Russian gas to peak during the cold winter months and sought to raise the stakes by massing troops on the Ukrainian border. And yet, although this move appeared to be a poker-style bluff, it wasn’t all about America’s and NATO’s apparent lack of resolve or lack of willingness to uphold our 1994 Budapest Memorandum obligations.

Putin may have calculated that despite Biden’s personal resolve and deep commitment to European security, he simply lacks the ability to call Putin’s re-raise because domestic discord and the fractured global system no longer afforded him a sufficient amount of discretionary “chips.” The very nature of a game like poker or backgammon is that you never know if the opponent is calling or taking until you raise or double them. No amount of pre-game chatter commits one to action until the chips are actually down. So, it is true that trial balloons were launched about kicking Putin off the SWIFT system if he re-invaded Ukraine in 2022. But we had previously said we would uphold the Budapest Memorandum of 1994 committing the U.S. and the U.K. to defend Ukrainian territorial integrity but then didn’t do anything when Crimea was annexed in 2014. So Putin had every reason to believe that Western statements leading up to the invasion were in fact hot air.

Now let’s finally drill down yet further and consider the events of the past few months as a single hand of poker (I prefer to imagine it as a hand of the wildly complicated Pot Limit Omaha variation of the game, but you can imagine it as No Limit Hold ’Em if that makes the description easier to follow).

The pre-flop action saw Putin making a less-than-pot-sized raise and despite having the nuts, we limped. Now to the post-flop action, we look at the board and are distracted by our mobile phone (a text from our NATO allies complaining about something) and we don’t realize that we are still holding the nuts. So, we check. This is how I would model the fact that Olaf Scholz and Biden didn’t hold a joint press conference three weeks ago in which they could have said, for example, that if you so much as invade any part of Ukraine, we will kick all of Russia off the SWIFT code system, sanction the Central Bank and send tons of arms to Ukraine, and Germany will permanently cancel Nordstream II and double its defense budget. We had the nuts.

We could have staged this big joint presser and showed Putin that we had the nuts. Moreover, we could have even counter-bluffed by holding a conference with Sweden and Finland saying that they would join NATO if invaded, even if they weren’t actually committed to doing so. But we didn’t do any of this, so although we stated during the side action over the table that we had a strong hand and that Putin better be careful, the way we merely intimated dire consequences instead of spelling them out seemed to Putin to indicate that we were bluffing.

Why did we fail to get our message across to Putin? It seems that our leaders had the wrong model of diplomacy to hand. They weren’t viewing it as poker but rather that Putin was a chess player who when confronted by the correct moves on our side would be content with maximizing his interests by accepting a draw especially as he was playing black. Fundamentally, Scholz and Macron thought they could engage in negotiation rather than deterrence. But a hotheaded narcissistic sociopath who loves giving pushy raises understands only deterrence and threats of force. Flying to Moscow for talks was clearly perceived as a sign of weakness, not as the face-saving off-ramp from the crisis it was intended to be.

Given our lack of post-flop aggression, and Putin’s misreading of the meaning of the negotiation strategy, he made the biggest raise in the history of our iterative heads-up action. Like a veteran hustler finally ready to pounce, he did so nonchalantly and abruptly. He was banking incredibly hard that, given our previous tendencies and his read on our current hand, we would insta-fold.

The opposite happened. The West has collectively called Putin’s bluff; he is flabbergasted and tilted. Now the turn card has come and it is giving us both the top pair along with outside straight and flush draws (in Omaha it is possible to have both simultaneously), while all Putin has is an under pair and a gut shot at a non-nut straight draw. To conceal this weakness, he is tempted to raise yet further with comments about readying the nuclear arsenal and leveling Ukrainian cities. Possibly he is hoping that both the Ukrainians and their Western allies will gradually back down once they see that his brutal aggression will not be deterred by sanctions. Certainly he wishes for an outcome that would turn his earlier misread into some form of genius.

As soon as we think of the current crises in these poker terms, the risk for even further miscalculation becomes manifest. We may have inadvertently “tilted” Putin, through our bizarre behavior of not raising post-flop even though we had the nuts, but then calling Putin’s bluff mega-raise. Furthermore, it may now actually be the optimal strategy for Putin to jam in his remaining chips, out of an attempt to defend his earlier unwise raise.

This is the issue of pot odds. When one has already placed a very high percentage of one’s stack in the pot, it makes little sense to fold, even if one intuits an adversary’s call to indicate that one is a significant underdog. As such, Putin seems to find himself in a situation in which it is highly rational for him to seek to escalate matters in Ukraine striving to win at all costs even though he has a very slim chance of doing so. Withdrawing now or negotiating a settlement perceived as bad for Russia would crater his domestic legitimacy, broadcast his weakness internationally, and expose his earlier bluff as a complete blunder. Also due to Putin’s sunk costs, it may be worth risking a complete defeat, even if the odds of victory remain quite slim.

Finally, as an agent of what I term in my recent book the Enduring Disorder, I see Putin as benefiting from a disordered world system. As such he does not seek to impose a coherent alternative non-Western order on Ukraine, but similarly with other strategic theaters like Syria, Libya, Venezuela and Iran is happy for these theaters to remain disordered basket cases. He may feel that even if the Russian economy implodes and Ukraine is reduced to rubble this is a win for his vision of the world. It is certainly not a win for the West or for the Ukrainian people.

A wise strategy for the West would have been in the early post-flop action to have either aggressively bluffed ourselves or to have made very clear exactly what we would do if Putin escalated. We could have threatened offensive cyber-attacks or limited nuclear strikes as a way to deter the Putin post-flop raise. However, it seems that European leaders were genuinely only willing to engage in negotiations rather than deterrence. Negotiations were however a completely inappropriate strategy as they only work when the adversary has legitimate grievances which can be solved via some sort of optimal compromise. This assumption clearly never applied to a sociopathic bully like Putin. Because we adopted this suboptimal negotiation ploy which was perceived as indicating a lack of resolve and poor coordination within the Western bloc, this engendered a further suboptimal play from Putin, the highly aggressive post-flop raise, when he was facing an opponent actually holding the nuts.

The mathematics of the pot odds have now made both sides existentially committed to this hand going all the way to the River. It is this fact that makes it manifest that the West is truly at War with Russia in a way that we never were in the solely proxy wars over Syria, Georgia, Libya or the Donbas.

Given that we are at war, if our goal is to genuinely help our Ukrainian allies, avoid future bloodshed and avert the war going nuclear, we should do a lot more than publicly share intelligence on Putin’s actions and arm the Ukrainians with stingers. One approach would be a massive bluff ultimatum threatening extreme measures, both financial, cyber, or nuclear, if our conditions are not met by a certain time. Although this might work, it is unlikely to be adopted unanimously by the Western bloc leaders and could lead to Putin either calling our bluff or pre-emptively escalating himself.

Another approach better suited to the temperament of the West’s leaders and the expectations of our populaces is resolute deterrence. Major Western leaders should hold a joint news conference spelling out their exact redlines, laying out all the financial, cyber, and nuclear retaliation that we have in store. It is normal poker etiquette when both sides are all in to flip over their hole cards before the final board cards are dealt. If the Western aim is to bleed Putin dry over many years through a protracted insurgency in Ukraine, I believe they should say so. If a single cyberattack on a NATO member will trigger a nuclear World War III, I believe they should say so. If a certain amount of killing of Ukrainian civilians will lead to a complete blanket boycott on Russian hydrocarbon exports no matter the pain this will cause to European consumers, this redline should be explicitly stated.

Yes, it could have saved tens or hundreds of thousands of lives if we had made these declarations a few weeks ago. But it may still avert a future catastrophic miscalculation by letting everyone know now exactly where we stand.