It is a pity and a paradox that Jafar Panahi — Iran’s most important living filmmaker, in my judgment (at least among those I’m familiar with) — seems to be valued in the West more for his persecution than for his filmmaking. His first feature, “The White Balloon” (1995), became the first Iranian film ever to win a major award at the Cannes Film Festival (the Camera d’Or), and his four subsequent features — “The Mirror” (1997), “The Circle” (2000), “Crimson Gold” (2003) and “Offside” (2006) — all won awards at major festivals. But it wasn’t until Panahi was arrested in 2010, sentenced to six years in prison and banned from all filmmaking activities for the next 20 years that he was noticed in the mainstream press in the West. (He was charged with “propaganda against the system” for attending the funeral of a student killed during the 2009 Green Movement protests and for attempting to make a film sympathetic to that rebellion.)

Since then, Panahi has miraculously managed to make five more features in defiance of the ban, appearing as himself in each of them. Severely limited in terms of their resources and shooting conditions, the films have nonetheless garnered more attention than the five features made between 1995 and 2006, prior to his arrest. All five of the earlier films were produced with state money, though several were banned in local theaters in Iran at various points.

The first of Panahi’s post-arrest features, “This Is Not a Film” (2011), was shot exclusively in Panahi’s living room when he was under house arrest. The most recent, “No Bears” (2022) — shot near the Iranian-Turkish border and with a far more complicated storyline — won the Special Jury Prize at last year’s Venice Film Festival. Sadly, these fugitive works are much better known by the public than the far more accomplished and nuanced features Panahi made before 2010. It’s worth adding that “The Circle” and “Offside” both offer blistering critiques of the treatment of women in Iran, and “The White Balloon” and “Crimson Gold” are incisive explorations of class dynamics and disparities.

There are two particularly striking aesthetic traits that all 10 of Panahi’s features to date have in common: a grounding in documentary techniques common to both Italian Neorealism and the films of Panahi’s principal mentor, the Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami; and a self-referential and modernist view of cinema itself as part of each film’s subject — also traceable in part to Kiarostami and often including the impression that the film is unfolding in real time. This is especially true of “Offside,” much of which was shot in and around Azadi Stadium in Tehran during the actual World Cup qualifying match that Iran and Bahrain played on June 8, 2005.

Kiarostami, one should add, began his own film career by founding the film unit for the state-run Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, better known as Kanoon, which freed him from the usual commercial constraints but also made his early films somewhat didactic in nature. Panahi inherited some of his role model’s didacticism, or his pedagogical tone, as well as his modernism — as seen in “The Mirror,” which oscillates ambiguously between the adventures of a little girl trying to find her way home from elementary school and the adventures of the little-girl actress who has been playing her for Panahi’s film crew and who now wants to quit and go home.

Even more pedagogical — and modernist — is “The Circle.” In many respects, it is Panahi’s greatest and boldest film (as well as one of those that were banned in Iran), a sustained cry of rage against the brutal treatment of women in Iranian society, stretching over a single day, from the birth of a baby girl in a hospital to the incarceration of an adult in a penitentiary. The implication is a circular journey from one prison to another. Above all, “The Circle” both anticipates and clarifies many aspects of the “Woman, Life, Liberty” uprising that has shaken the country to its foundations more than two decades later. Much of the film’s narrative unfolds in circular camera movements traversing circular locations. But no account of Panahi’s range can exclude his flair for comedy in both “The White Balloon,” about the efforts of a little girl (Aida Mohammadkhani, the sister of Mina Mohammadkhani, who would play the lead in “The Mirror”) to buy a lucky goldfish for the Iranian New Year; and “Offside,” about girls in Tehran who masquerade as boys so they can watch a soccer match at Azadi Stadium but get busted for it. (In the Islamic Republic, women are banned from attending men’s sporting events.)

Both of these comedies, to be sure, also have their instructive, even didactic sides. “The White Balloon” ends with its middle-class heroine thoughtlessly snubbing the working-class boy who helped her out. And “Offside,” which, like “The Circle,” culminates inside a police van with arrested females, extends some of its empathy to the guards who are obliged to arrest the girls — both groups being viewed as comic victims of the same draconian laws. An equal-opportunity satirist, Panahi derives much of his comedy from this situation, so he can pass freely back and forth between these groups without ever losing his satiric focus. Indeed, the movie ends on the street with both the girls and the soldiers leaving the van with sparklers to join the ecstatic crowd, patriotically singing the Iranian national anthem to celebrate their team’s victory.

In a 2016 documentary short called “Where Are You, Jafar Panahi?” we follow Panahi as he drives a colleague to visit Kiarostami’s grave on the outskirts of Tehran while recounting how all his pre-arrest films describe Iranian society as he saw it, out on the streets, but all his post-arrest films can describe only his own situation, removed from that society. This explains, in a nutshell, why his earlier, ignored features have more lasting value than his recent ones, however much the recent ones testify to Panahi’s resilience and ingenuity.

To appreciate his earlier works, one needs to understand non-Western societies, where being able to smoke a cigarette if you’re female has a different significance than in the West; where dress codes for women are enforced — sometimes brutally — by the authorities; and where laws governing marriage and divorce impose strictures on women. But ignoring these matters makes it much easier to identify with Panahi not as a social analyst or critic but as a martyr.

Panahi’s “Crimson Gold” is the powerful and haunting saga of a pizza deliveryman and veteran of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) who winds up attempting to rob a jewelry store before shooting its owner and then himself. It was inspired by a newspaper story discovered by Kiarostami, who wrote the screenplay. At the heart of the film are social class differences and the resentments felt by wounded veterans — painful issues that are far closer to our own in the West than the issues taken up in “The Circle” and “Offside.” But if we don’t even know the differences between Iran and Iraq, we’re likely to feel more comfortable with dissident acts such as Panahi’s than with his vibrant works of art.

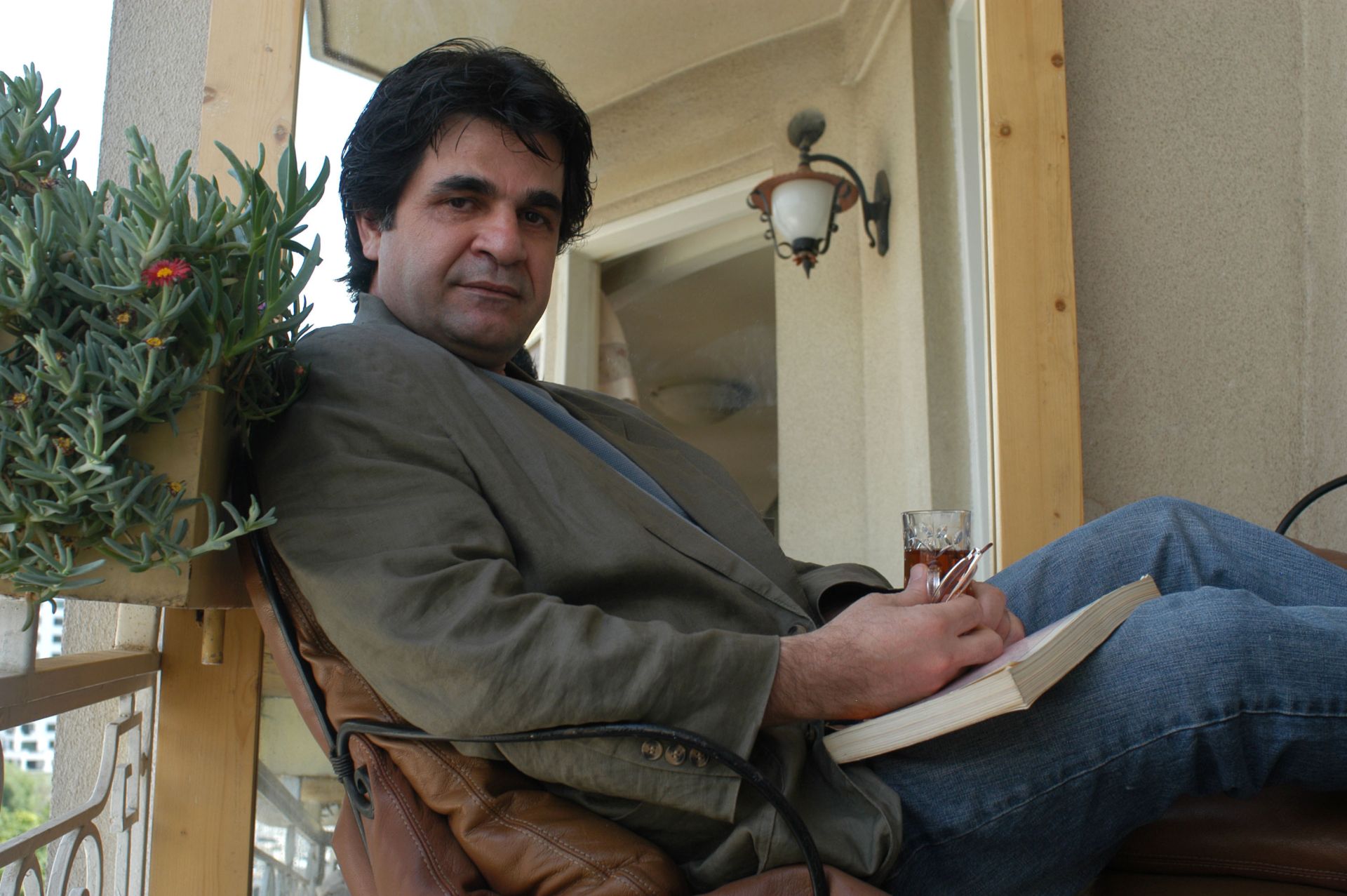

Who is Jafar Panahi? He was born in 1960 into a working-class Azeri family, with four sisters and two brothers, in the town of Miyaneh in Iran’s East Azerbaijan province. He had a long apprenticeship, during which he made several shorts and documentaries, initially while serving for two years as an army cinematographer in the Iran-Iraq war and then as assistant director on Kiarostami’s film “Through the Olive Trees” (1994).

There is such pervasive ignorance about Iran in the West that we tend to view it as a monolithic blob, when in fact it is a highly multiethnic and multilingual society. While Persians are the majority, roughly 40% of Iranians belong to other ethnic groups — Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis, Lors and Turkmen. Panahi grew up speaking Azeri in his own family and Persian with other Iranians. (His most recent film, “No Bears,” features both Persian and Azeri throughout.)

We must also ask: What about Panahi’s politics and political courage? What were some of the volatile conditions that eventually compelled him to go on a hunger strike in prison in February 2023? And why did the government decide, two days later, to let him return to his home? My own brief encounters with Panahi, my two visits to Iran and what I’ve learned about Iranian filmmaking and censorship provide some insights regarding the years leading up to February 2023.

Note, for example, Panahi’s courage when, after being arrested for the first time, he asked his jailers not to accord him any special treatment because of his celebrity status as a filmmaker. In fact, becoming a filmmaker is one of the only forms of upward class mobility available today to working-class Iranians. (This fact even provided Kiarostami with the focus of his groundbreaking early feature “Close-Up,” which follows, recapitulates and even extends the real-life story of Hossain Sabzian, a poor Iranian cinephile who impersonated the real-life filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to gain the social acceptance of a wealthy Turkish family in Tehran by claiming that he wanted to make a film with and about them, until he was arrested. In the film’s final sequence, Kiarostami staged a real meeting between Makhmalbaf and a now-freed Sabzian so the two of them could pay a visit to the home of the Turkish family.) The same sorts of tensions lead to the devastating violence at the conclusion of “Crimson Gold.”

When I briefly interviewed Panahi through an interpreter about “The Circle” (when it was screened at the Toronto Film Festival), I was startled to find him insisting that the film wasn’t political — a claim that struck me as tantamount to stating that pork was a vegetable. But in another interview about the film, he explained his reasoning more precisely:

A political filmmaker commits to a certain ideology, tries to propagate that through his work and attacks opposing ideologies. In “The Circle,” I am not attacking or supporting anyone. I am not saying who’s good and who’s evil. I am trying to look at everyone from a humanistic point of view and hold a mirror that reflects social realities. It’s up to the audience to interpret those realities in political terms if they wish to do so. I have made an art film with a message of protest, not a subversive political film.

It’s the sort of distinction that might sound arcane to a North American but is logical if one considers the more recent case of an Iranian filmmaker I met in Tehran in 2018, who was making daily visits to Iranian censors, trying to convince them that it wasn’t politically subversive to show the lead actress smoking cigarettes in his latest feature.

Even back in 2001, when Panahi was flying from a film festival in Hong Kong to others in South America, with a change of planes at JFK Airport in New York, he got so sick of being treated as a criminal by being fingerprinted every time he passed through U.S. customs that he refused to go through the ritual again. The result? He was shackled to a bench for over a dozen hours in a room full of “illegal aliens,” not allowed to phone anyone and then sent straight back to Hong Kong with his hands and feet in chains, even after he showed evidence of who he was and where he was going. After all, the fact that “The Circle” won the Golden Lion at the prestigious Venice Film Festival the previous year didn’t necessarily mean that he as an Iranian might not have managed to sneak a hand grenade through the metal detector in Hong Kong. One might even argue that the unreasonable xenophobia of U.S. Customs officials finally forced him to become political, despite himself.

It also seems ironic that Panahi was treated as a criminal in his own country nine years later, which was three years after making “Offside,” his most lighthearted comedy and most accessible and entertaining movie. But acknowledging the intolerance shown toward Panahi by both U.S. Customs and Iranian censors suggests a similarity between these two multicultural countries that we’re reluctant to see or acknowledge. Despite the Islamic Republic’s draconian laws and suffocating repression, Iran still produces what is arguably the most humanist cinema in the world. Panahi, one of that cinema’s greatest and most exemplary figures — and indeed, for that reason, one of the world’s finest filmmakers, not just Iran’s — deserves to be appreciated not simply for his courage as a rebel but for his talent and imagination in showing what the best filmmaking entails.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.