As the legend goes, in the 16th century Prague’s Jewish ghetto was under assault. Hoping to protect his people from slaughter, a rabbi conjured a new entity. Using his hands, he slowly shaped the figure of a man from clay. The rabbi then blew into the nostrils of his creation and whispered the name of God into its ear. Thus animated, the intended savior became a monster, embarking on a furious rampage that killed everyone in sight. This creature is known in Jewish folklore as the golem.

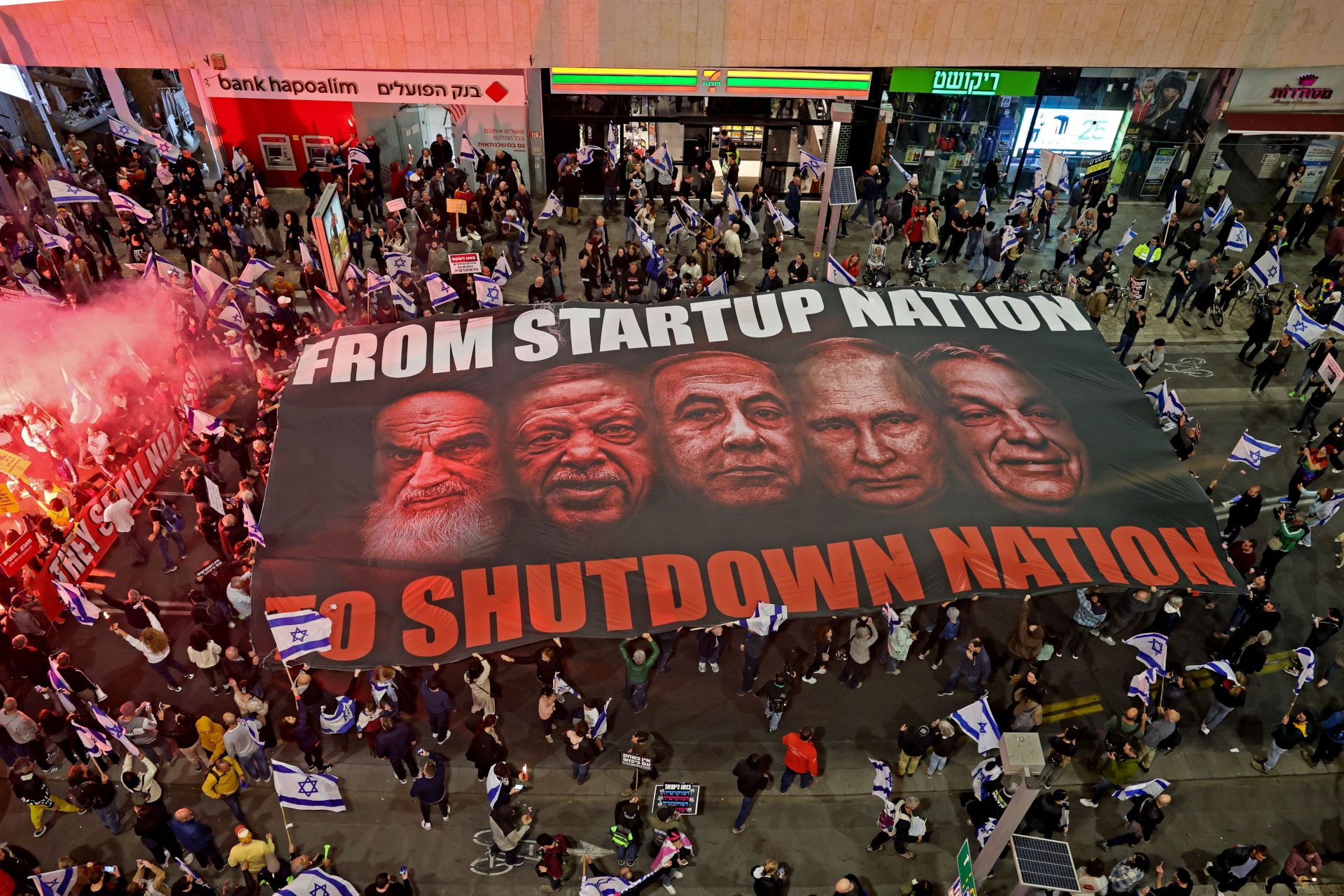

To borrow this metaphor of unintended dark outcomes, Israel can now be described as under assault from a new golem, created by radical religious and ultranationalist zealots to battle imagined enemies. Having attained unfettered power, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s coalition of four political parties (Likud, the Religious Zionist Alliance, United Torah Judaism and Shas) purports to rescue Israel from globalist elites, mainstream secular Jews and those they regard as “violent Arabs.”

The parties seek their country’s “salvation” by stripping Israel’s judiciary of its power, destroying the checks and balances needed to sustain liberal democracy, and allowing the reimposition of some religious laws, from bans on leavened bread in hospitals during Passover to discrimination against women. They also seem poised to rub out the so-called “Green Line” marking the 1967 boundary between Israel and the West Bank, undertaking a de jure territorial expansion by annexing portions of occupied Palestinian land.

Eight months after they took power, two of the coalition’s guiding principles stand out: “The government will take steps to guarantee governance and to restore the proper balance between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary” and “The Jewish people have an exclusive and inalienable right to all parts of the Land of Israel. The government will promote and develop the settlement of all parts of the Land of Israel — in the Galilee, the Negev, the Golan and Judea and Samaria ” (i.e., the occupied West Bank).

How have religious parties, originally at odds with secular Zionism, unified with the secular right? Why is Israel’s political terrain fertile for such volatility and excess?

But first: How did we get here?

Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence called for the swift drafting of a constitution, which the Knesset (Parliament) intended to achieve through a series of foundational laws, known as basic laws, but this never happened. In 1958, the Knesset enacted 11 Basic Laws, which were capable of being revised and expanded, and which were subsequently added to. The most consequential of the Basic Laws for the present crisis are the Basic Law on Human Dignity and Liberty and the Basic Law on Freedom of Occupation (i.e., professional occupation), which were adopted in 1992 and revised in 1994.

These laws contained nearly identical limitation clauses: They were not to be violated “save by means of a law that corresponds to the values of the State of Israel, which serves an appropriate purpose, and to an extent that does not exceed what is required.” The Supreme Court understood these clauses to elevate the Basic Laws over all other laws and to afford the court the power of judicial review. That power of review, including the passing of judgment based on the unreasonableness of any decision or action of the Israeli cabinet, has been amended by the current coalition.

The “reasonableness” standard has a long history in British law and has been part of the Israeli legal system since the establishment of the state. It applies only to administrative decisions, not the Basic Laws. It cannot be used to strike down legislation, but it can be invoked to prevent appointments, which are administrative in nature. Aryeh Deri, founder of the Shas Party (the Mizrahi, or Arab-Jewish, religious party), has been convicted three times of criminal offenses. Appealing both to the terms of Deri’s plea bargain and to the “reasonableness” standard, the court ultimately disqualified him in January 2023 from serving as health and interior minister.

At the same time, Israel’s right-wing coalition pushed an unprecedented package of legislation to limit the power of the judiciary. These proposals prompted an indefatigable protest movement, bringing hundreds of thousands into the streets week after week. One of the most egregious proposals, which Netanyahu says has since been dropped, would have given the Knesset the ability to overturn Supreme Court decisions by a simple majority vote. Changes still in the works will give the legislature more authority over the appointment of judges, and a particularly critical piece of legislation has already passed: a highly contested bill preventing the Supreme Court from halting government decisions it deems unreasonable.

The Supreme Court’s decision on Deri imperiled Netanyahu’s coalition, provoking the Cabinet’s backlash. On July 24, after the opposition walked out in protest, the Knesset voted 64-0 to limit the Supreme Court’s use of the “reasonableness” standard. That night, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets, sometimes challenged by police. On Sept. 12, the entire 15-member Supreme Court began considering an appeal against this Knesset overhaul of the “reasonableness” standard. In other words, it will essentially be ruling on a law passed against its own authority. The result, which could come as late as January 2024, will certainly create further havoc.

In the midst of these protests, an Israeli friend who is on the front line of the protest movement recently told me that the problem was not just Netanyahu’s corruption trial and his move to curtail the power of the Supreme Court. It was more fundamental, he said, going back to the relationship between state and religion, and to the occupation.

He is correct, but it is even deeper than that. It is also about the widening economic gap, the demise of the progressive camp and a political void that has been filled by the rise and recent consolidation of a united religious and secular right. Similar factors have also contributed to the rise of illiberal political forces in other parts of the world.

It is true that Netanyahu’s impending prosecution compelled him to make unprecedented concessions to religious and nationalist zealots like Itamar Ben-Gvir, Bezalel Smotrich and Deri. But his bid to avoid jail is clearly only one aspect of the unfolding story. Should the protest movement succeed in ousting the current government, it will still need to address these larger questions if democracy is to be sustainable in the long run. This will not be easy, but it is both possible and essential.

The lack of a clear separation between state and religion started with Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who envisioned a state that was both Jewish and democratic. Trying not to alienate the rabbis, the secular socialist leader allowed Orthodox Judaism to be recognized as the official form of Judaism to be subsidized by the state. He also enabled Orthodox rabbis to maintain control of family law (divorce and marriage laws). For Ben-Gurion, this concession gave religion a prominent but limited space in government. In his words, it was “a compromise that was accepted in order to prevent a war of the religious against the secular and a war of the secular against the religious.” By co-opting the religious establishment, Ben Gurion thought he could better control it.

Ben-Gurion’s compromise between religious and progressive secular forces seemed to work for a time, until the emergence and ultimate convergence of religious and nationalist political movements. The anti-Zionist ultra-Orthodox (or Haredim), religious Zionists and right-wing revisionist nationalists were initially at odds with each other, and were marginalized by the initially dominant Labor Party. Yet after the Camp David peace process unraveled in 2000, they gained significant political influence, tilting Israeli governments toward the center right and more recently to the far right.

This trend did not occur overnight. The extreme right-wing movement was instrumental in this transition, finding fertile ground thanks to a long history of failed peace processes with the Palestinians, two intifadas (Palestinian uprisings), widening economic inequality associated with the rise of neoliberal economic policies, domestic social fragmentation and recurrent political paralysis. All this combined to darken the skies and harden right-wing movements among both Israelis and Palestinians. In this volatile climate, Orthodox Judaism gained traction alongside enhanced settlement construction in the West Bank. Seeking to achieve longstanding claims of ownership over “Greater Israel” by divine right, the increasingly influential Orthodox parties have eroded the secular character of the Israeli state.

Liberal-democratic states tend to be imperiled when the elevation of religion or culture competes with the state’s original cosmopolitan intent. In “The Philosophy of Right,” the 19th-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel described the tendency of liberal states to oscillate between the state of law and the state of culture. The amalgamation of law and culture may be a necessary component of the liberal state, but it becomes dangerous when cultural and religious claims are elevated at the expense of the universal rule of law. In the Israeli case, such a conflict arose from the state’s struggle to preserve its Jewish character despite the universal human rights commitments in its Declaration of Independence.

This difficult liberal-democratic balancing act is not unique to Israel. A similar course of events has already played out in many societies that have witnessed the rise of right-wing populism, often with a subtext of religious justification, in places like Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, Brazil under Bolsonaro, India under Modi and the United States under Trump. For the ruling elites of these countries, democracy, human rights and an independent judiciary come to be seen as impediments to the implementation of order amid chaos and their broader providential or nationalist designs.

Democracies can indeed become illiberal, retaining some democratic processes while abandoning fundamental commitments to universal human rights. Despite their differences, religious and secular nationalist forces often align well in their defense of the traditional family, which lies at the core of their vision of cultural and political order, in working against LGBTQ+ and women’s rights and in portraying immigrants and minorities as a threat to established ways of life, both economic and cultural. Over the past 20 years, same-sex couples and their families have won many legal protections in Israel, including rights regarding inheritance, stepchild adoption, divorce and surrogacy, often helped by rulings of the Supreme Court.

As in Hungary, however, these laws could be rolled back by the current strong ultra-Orthodox and nationalist predominance in government. Yitzhak Pindrus, a senior member of the United Torah Judaism party, part of the ruling coalition, recently called sexual permissiveness and LGBTQ+ rights “the most dangerous thing to the State of Israel.” Finance Minister Smotrich openly opposes LGBTQ+ rights, and he is probably correct when he says that those who elected him do not object to his position.

Netanyahu is now following, to the letter, Victor Orban’s authoritarian playbook. But it goes deeper than mere opportunism, ignoring Orban’s evident antisemitism: “It is a great mistake to think that Netanyahu’s courtship of the European far-right is only a matter of realpolitik and a defense of political interests,” the late Israeli intellectual historian and fascism scholar Zeev Sternhell argued in his 2019 essay “Why Benjamin Netanyahu Loves the European Far-Right.” Not only do Netanyahu and his allies “collaborate willingly with this Trojan horse, which aims at destroying the fabric of the liberal values of the West,” Sternhell wrote, but they see Israel “as an integral part of this anti-liberal bloc led by nativist xenophobes who traffic in anti-Semitic conspiracy theories such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Poland’s Jaroslaw Kaczynski.”

Toward outsiders, Netanyahu takes cynical pride in the protest movement, describing it as proof of the vibrancy of Israeli democracy. He contends that his Cabinet is taking only minor corrective measures to recalibrate the system of checks and balances. In reality, if the Supreme Court blocks this controversial law, Netanyahu has said he may not abide by its ruling. Such a move on his part would constitute a regime-launched coup, accelerating a descent into full-on authoritarianism.

But the democratic problem is not only within Israel’s 1967 borders. While right-wing populist leaders always scapegoat specific ethnic groups, Israel has for over half a century occupied a territory without granting rights to its inhabitants. This presents an intractable problem for internal democracy.

After the 1967 Six-Day War, the Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz argued that ruling over the Palestinians would “effect the liquidation of the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people and bring about a catastrophe for the Jewish people as a whole.”

By the November 2022 elections, Israel’s center-left parties were unified by little more than their opposition to Netanyahu, and Arab voters felt more alienated than ever. In that political void, the seemingly odd bedfellows of the secular Likud and the religious parties emerged as a consolidated ideological bloc. Religious Zionism purports to represent a new synthesis, the glue to unify Jewish Israelis under Jewish religious law and principles. Along with ultranationalists, they call on all Israelis to focus on security and the economy, return to Jewish religious tradition and entrench the expansion of the state. Religious conservatives and ultranationalists agree that more settlements, leading to the final annexation of portions of the West Bank, are the only solution to the continuing threat of violence.

To clarify, under the 1994 Oslo Accords, Area A of the West Bank, which includes most major Palestinian cities, is governed and policed by the Palestinian Authority; Area B is under shared Palestinian and Israeli administration; and Area C, which includes an expanse of sparsely inhabited territory, is under Israeli civil and security control. In reality, Israeli security forces enter all three areas, and the state enforces an egregiously segregated legal arrangement in Area C, enforcing Israeli law for the Jewish settler population and military law for Palestinians in the context of occupation.

While expanding settlements have already resulted in Israel’s de facto annexation of Area C, Netanyahu’s current ruling coalition aims to make the annexation official and permanent. The overhaul of the Supreme Court would make that process easier. While critics see the Supreme Court as little more than a rubber stamp of the Israeli government, it has long served as the last court of appeal for Palestinians seeking to thwart draconian military injunctions and to retain property rights against trespassing settlers. That judicial protection of Palestinian rights, however limited, will vanish if the government’s plan becomes law.

Despite civil disobedience and waves of protest, the right-wing coalition that makes up Israel’s 37th government moves forward like a golem, undeterred and confident that its dominance in the Knesset will be sustained by the demographic rise of the ultra-Orthodox population. Yet the government is more fragile and conflicted than it appears. It is, after all, unified only by a dysfunctional marriage between secular and religious ultranationalists, who fear a backlash from their constituents as they fail to address rising inflation, deepening economic problems and ongoing security threats.

In fact, the country cannot be managed without the main actors of civil and political society the government now attacks, including the business and military leaders who have been withdrawing their support. Seventy percent of Israeli startups have taken steps to relocate or move their money out of the country since the judicial reform crisis began.

More than 10,000 reservists from dozens of military units have said that they will not report for duty if the legislation passes, including 500 reservists in military intelligence, more than 1,100 air force reservists and over 400 pilots. If any one of the four parties in power feels betrayed by false promises, they could withdraw and bring down the government. Should that happen, recent polls indicate that Netanyahu’s coalition would not be returned to power. Israeli society remains deeply divided, and Netanyahu’s loyal and impassioned base, like Trump’s in America, represents a minority. While Netanyahu is the longest-serving prime minister in the country’s history, a Netanyahu-led Likud Party has never crossed the 30% threshold in a general election. In 2022, the anti-Netanyahu coalition would still have won had they been more unified and, especially, if the Arab parties had turned out en masse and joined them.

The opposition (both the formal opposition in the Knesset and the informal opposition in the streets) has lost a critical battle. But can it win the war to save Israeli democracy? This will not be easy. One possibility would be a return to the status quo ante. A progressive political leader told me in a recent conversation that, if all hell breaks loose, a presumably post-Netanyahu Likud could convene a new government in coalition with the more centrist parties led by Benny Gantz (head of the Blue and White Party) and Yair Lapid (head of both the Yesh Atid party and the opposition in the Knesset).

This option may not need to involve Arab parties. Although this outcome would fit the short term “management of crisis” style adopted by many Israeli political leaders from all sides of the political spectrum, it would not solve the deeper crisis: the core division within the Jewish population between liberal secularism and religious nationalism.

Jewish fundamentalism is an albatross for Israeli democracy that is not about to disappear unless the source of its influence is tackled directly. Rabbis are no longer playing second fiddle as they did in the early days of the state, when many ultra-Orthodox parties opposed the secular Zionist project. They have now secured entrenched power in Likud’s coalition, extracting significant subsidies for religious education and economic welfare, while sparing themselves from military service.

Further, they are catering to the views of a young generation of religious voters who want more than Orthodoxy and have adopted ultranationalist beliefs. Just as in Max Weber’s time, religious leaders are convinced that “the fate of their times” is characterized by unreliable science, “by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the disenchantment of the world,” animated by greed and materialist pursuit. Their followers have long felt overlooked, marginalized and relatively poor compared with the rest of the population. They see Judea and Samaria as the extension of their promised land.

Even if achievable, a return to the status quo ante will not secure the stability and longevity of Israeli democracy. That would require a broader coalition, including the involvement of Arab parties (formed by Palestinians who are Israeli citizens) in the next government. Considering that Arab Israelis constitute one-fifth of the electorate, they have consistently punched below their weight. They benefit from welfare and political rights and are currently represented by four Arab parties, though many rightly complain that they suffer from structural discrimination. Along with the general fragmentation of the opposition to Netanyahu, Arab interparty divisions and chronically low Arab turnout enabled the November 2022 return of Netanyahu and his ultra-right government.

Arab Israelis — the most vulnerable citizens to be affected by the judicial overhaul — can no longer stay on the sidelines of the protest movement or outside the government itself. With the exception of Ra’am’s inclusion in the 36th government of Israel, led from June 2021 to December 2022 by Naftali Bennett and Lapid, no Arab party has ever been a formal member of the ruling coalition. It is time for defenders of Israeli democracy to integrate the Arab parties in anticipated government coalitions. Despite the longstanding refusal of Arab parties to join any Israeli government (as a general protest against the occupation) and Jewish parties’ historical opposition to including Arab parties in government (for their perceived lack of loyalty to the state), it is time for defenders of democracy to break these stalemates; both sides need to envision the inclusion of Arab parties in a future governmental coalition and in support of democracy.

The aggrieved groups have been pitted against each other, a process with a tragicomic dimension well captured by Israeli comedian Yohay Sponder:

There are Jews, then below them there are Christians and Druze together; then below them there are the Arabs who are with us; then below them there are Arabs who are against us; then below them there are the Palestinians. Above the ordinary Jews, there are religious Jews; above them, there are religious Zionists; above them, there is God; above God, there are religious Haredim; above them, there is Bibi; and above Bibi, there is Sara [Netanyahu’s wife].

In short, everyone is feeling oppressed and everyone agrees that the Palestinians are at the bottom of the ladder; they are, in effect, the “untouchables.” Against a hierarchy of oppression that now includes “the ordinary Jews,” only a renewed commitment to Palestinian rights can tilt the balance toward a more inclusive and sustainable democracy.

The Israeli protest movement has been reluctant to consider this change of direction. While the movement includes many different groups, and is funded heavily by the business community, the aim of its main organizers is, for now, to keep the broadest common denominator against the current government.

Brothers and Sisters in Arms, a group of reserve soldiers and officers from all units of the Israel Defense Force, supports that view, arguing that addressing the question of the occupation at this time would fragment the movement, given its disparate political allegiances. Others, such as Combatants for Peace, an Israeli-Palestinian group working together to end the occupation, maintain that it would be a mistake to neglect the central challenges of Israeli democracy, particularly at such a moment of heightened political consciousness in the Jewish population. They are right; envisioning an alternative to the occupation should be actively encouraged by those who champion democracy against autocracy.

This historical moment could constitute a turning point for Jewish Israelis, Palestinian citizens of Israel and those living in the West Bank. Whether such discussions happen on Kaplan Street (a major Tel Aviv site of the protest movement) or in a less confrontational environment, those who care about Israel and human rights need to confront the division between state and religion and offer alternatives to the subjugation of Palestinians in the territories, lest fanaticism be given the last word. To do otherwise would be a shortsighted approach to the survival of democracy. It is time to answer any sense of defeatism with Churchill’s sound advice to “never let a good crisis go to waste.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.