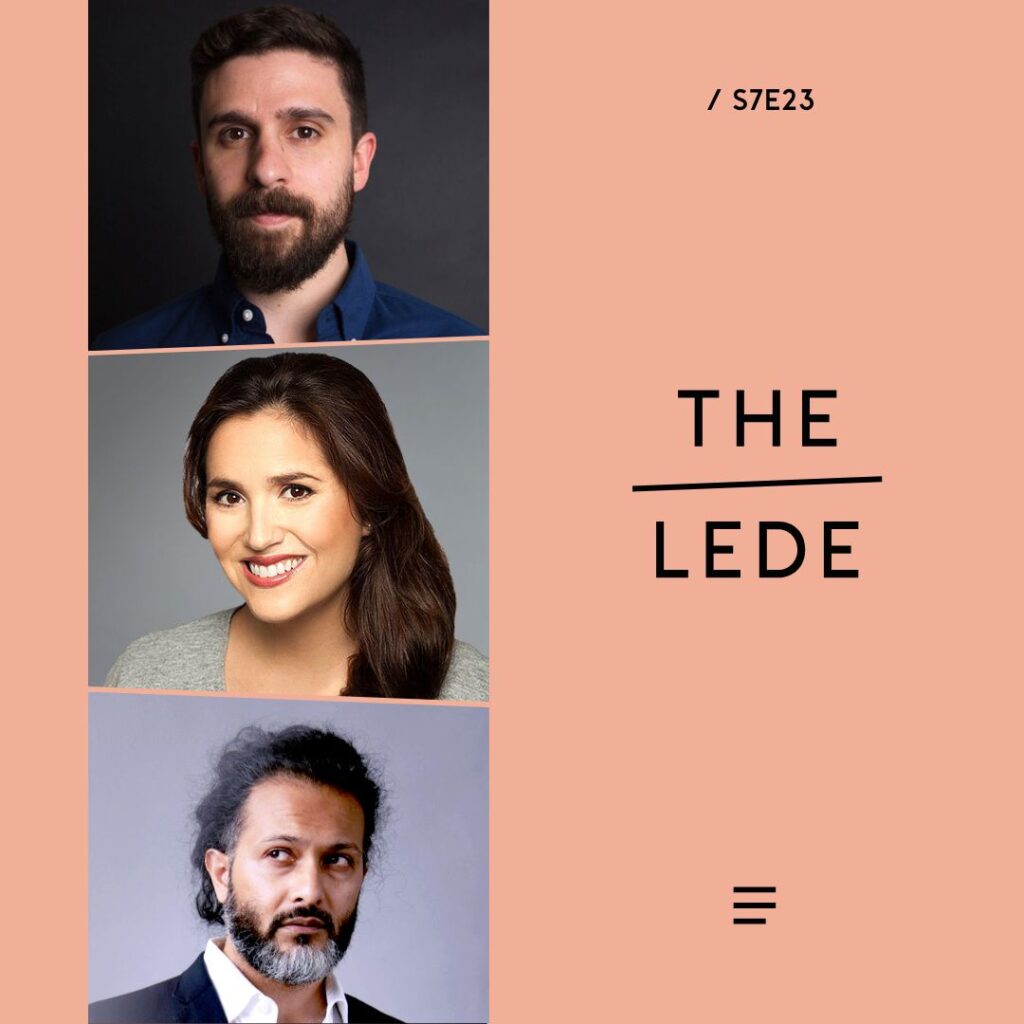

Hosted by Faisal Al Yafai

Featuring Christopher Miller and Amie Ferris-Rotman

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

Shortly after starting an interview for this week’s episode of The Lede, the Financial Times’ Ukraine correspondent Christopher Miller hears air raid sirens outside his Kyiv apartment. “I’m chatting with you, looking at my phone, and I got a text alert before the sirens started blaring. It says, ‘There’s an air raid alert, proceed to a shelter,’” he tells New Lines’ Faisal Al Yafai.

The sirens and accompanying missiles have become such a part of daily life that Miller stays on the line a little longer, happy to continue the interview.

“We’re at this real difficult moment where a lot of people feel like we’re standing perhaps on the precipice of something really bad.”

“What do you think that does to the mentality of people who are trying to go about their daily lives?” Al Yafai asks.

“People are mentally fried, they’re just exhausted,” Miller responds. “This has been three and a half years of war and an air campaign that’s only escalated in the past couple of months. Air raid alerts — now, we get them multiple times a day.”

Despite the efforts of U.S. President Donald Trump to pressure Russia into a ceasefire, threatening tariffs if a 50-day ultimatum period was not met, New Lines’ Global News Editor Amie Ferris-Rotman notes that the threat had been shrugged off by Russia’s deputy foreign minister, Sergey Ryabkov, within 24 hours.

“[Trump] claims he’s got leverage,” Ferris-Rotman says. “He’s going to put secondary tariffs on buyers of Russian oil like India and China. I personally don’t think that really works. Russia will sell its oil to people who want it regardless, as it has proven throughout this war.”

Elsewhere, the way the conflict is perceived is changing, Ferris-Rotman says. “Some countries have more at stake than others. The Baltics, for example, those former Soviet countries that border Russia, obviously they’re extremely keen to see this war end, to not have a victorious Russia. Their own security is at stake,” she says. “Then we have other countries like Poland, which was a huge supporter of Ukraine, which took in the lion’s share of refugees. Now that support has dropped.”

Those changing attitudes have also reached Ukraine, Miller says. “We’re at this real difficult moment where a lot of people feel like we’re standing perhaps on the precipice of something really bad. That is not just the escalation of Russia’s war, but perhaps the fracturing or collapse of this unity that we’ve seen in Ukraine over the past three years that’s kept it together and collectively against Russia.”