In February 2022, Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs (or Diyanet) landed in the news when it announced that performing the pilgrimage to Mecca in the metaverse does not count as a “real hajj.” The ministry’s head went on to specify that Muslims are free to visit Mecca in a virtual fashion. However, for real worship (“ibadet”) to take place, he opined that one’s feet must touch the soil around the Kaaba.

Responses to this decree on social media were swift and ran the gamut. Some individuals heartily agreed: They reasserted the primacy of the physical and material experience of the hajj, praising the irreplaceable sacrality of the earth surrounding Islam’s holiest site. Others of a more jocular bent, however, suggested shipping soil from Mecca and stepping on it while at home, thereby performing a religiously acceptable hajj without the hassle and cost of travel. For its part, the official body overseeing the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina sent a tweet correcting misperceptions, excoriating irresponsible news reporting and stating that Saudi Arabia had not launched a hajj in the metaverse.

The Diyanet’s comments sparked a social media conversation at the time, but what shape the metaverse will take is an ongoing discussion. Despite Facebook’s problems and the much-touted “meltdown” of the tech sector, there are many other attempts to explore this new technology, including for worship. This new type of virtual pilgrimage (or “v-hajj”) by Muslims active on the internet (or iMuslims) is nothing if not a product of our times. Its entanglements are many, from the technological to the interpersonal and political. What does this latest digital turn in Islamic devotional practices reveal about human creativity, and what are the place and future of Islam in an increasingly digital world? Can we now speak of a “virtual Islam” (or v-Islam) and, if so, what are its defining contours, visual languages and future potential? Both real and virtual innovations raise doubts about whether they can replace the “real thing,” but such doubts are not new, as seen previously with water bottles filled from the holy Zamzam well, “hajj selfies” and relics of the Prophet Muhammad like hair and clothing.

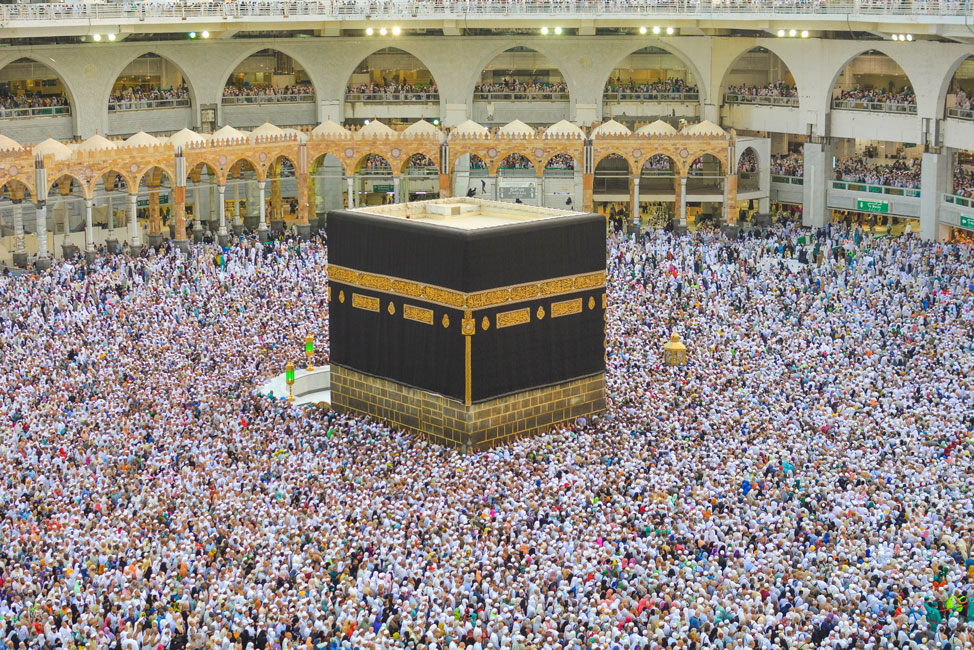

Let us start with the metaverse as imagined and promoted by Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg. Despite recent losses, this immersive virtual world is intended to lure and connect global audiences. Participants obviously include the world’s large Muslim population, which is estimated at 1.9 billion people today. Demographically, there is immense potential for scaling up the “Muslim metaverse,” especially if participants must pay a fee or are encouraged to make a donation to access some platform, application or resource, such as marriage counseling or electronic religious opinions (or e-fatwas). In the case of the hajj, lucrative metaverse add-ons could include token payments, charitable contributions or revenue-generating ads upon entering Mecca’s Holy Mosque, performing circumambulation around the Kaaba and touching the Black Stone. These are all key elements of the pilgrimage experience in Islamic traditions, in which they are enshrined as a pillar of the faith and a free public good. Put more simply: They are fully “open access” on the ground and in reality only.

Beyond the metaverse market, the virtual hajj also proves a testament to our COVID-19 era. The pandemic forced many to pray at home (either alone or via live streaming) and caused a temporary suspension of communal Friday prayers. Muslim pilgrims also faced curbs on hajj participation and had to abide by various health, hygiene and social-distancing rules. For example, in 2020 and 2021, Saudi Arabia capped participation and suspended the pilgrimage for foreigners, the unvaccinated and those with chronic illnesses. It also put in place a number of preventative measures, such as minimizing mass gatherings and requiring pre- and post-hajj PCR testing and quarantining. These logistical obstacles pushed eager pilgrims out of a coronavirus actuality and into cyber territory — a boon to the budding metaverse, no doubt.

Beyond responding to this pandemic tech-turn, the Turkish Diyanet’s decree functioned as a direct rebuke of Saudi Arabia’s “Virtual Black Stone” project. Launched in December 2021, the latter is billed as an “informative initiative” and a virtual reality (VR) means to promote — but not replace — the hajj. Falling under the umbrella of the larger “Medina Project,” its oversight fell to the imam of Mecca’s Holy Mosque, while its technological implementation was entrusted to experts at Umm Al-Qura University, also in Mecca. This virtual initiative allows users who have purchased a VR headset (or “Kaaba glasses”) to virtually rub the Black Stone. Like a censer, the three-dimensional replica of the Stone emitted an aromatic substance, offering the virtual pilgrim the opportunity to feel and smell it while listening to prayers streaming live from the holy city. The experience thus aimed to stimulate parts of the human sensorium, above all sight, smell and touch.

The initiative is so new that it remains unclear whether those wishing to visit the Kaaba virtually will have to connect via the metaverse. For now, what is clear is that some welcome this modern image-world in the digital domain, while others feel great unease about augmented and/or virtual reality. Critics inside and outside the country accuse Saudi Arabia of “tampering with religion,” a blameworthy innovation (“bida”) that some consider extrinsic to the Islamic faith or without firm foundation within its doctrinal reservoir. Conversely, supporters of the latest technology contend that VR is, in fact, a good innovation (“bida hasana”) that can strengthen and spread the faith, foster piety, stem traffic and promote a greener world at a moment of catastrophic climate change.

Enthusiasm and recalcitrance make for strange but steady bedfellows when it comes to religious systems and their relationship with image technologies. In Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and other global faith traditions, the love of images (iconophilia) often goes hand in hand with the fear (iconophobia) and destruction (iconoclasm) thereof. In the past, as in the present, image debates raged with every new invention or twist. Within Islamic traditions, the 20th century witnessed the arrival of the printing press, lithography, photography, film and digital media. All met supporters and detractors, especially photography, a technology that captures the light silhouette of sentient beings. For this reason, portrait photography was initially banned in Saudi Arabia, but then embraced as a tool in the “public interest,” since it helps bolster the Islamic faith and Saudi rule. Within this faith-and-state (“din-wa-dawla”) dyad, print photographs and digital images of Mecca and the Kaaba symbolically disperse and strengthen a Muslim sacredness across geographies both physical and psychological.

Anxieties surround other creative expressions linked to the Islamic pilgrimage, especially hajj photography and Kaaba models. While some clerics have issued e-fatwas banning “hajj selfies” as a form of showing off and fake piety, they have nevertheless become a widespread phenomenon over the past decade. They have joined emojis, the iPhone, Twitter and Instagram as a form of figural self-imagery that is digitally recorded, socially networked and difficult to control. Despite this, in 2017, Saudi Arabia issued a ban on hajj selfies in the mosques of Mecca and Medina, citing logistical concerns such as traffic and a desire to lessen “confusion and annoyance” for pilgrims. This rationale effectively sidestepped thorny religious adjudications and reduced the risk of further international fiascos.

Making models of the Kaaba has been similarly popular and contentious as of late. All over the world — from Dubai to Turkey, Iran, Malaysia, Kenya, New Jersey and beyond — students and adults celebrate or prepare for the hajj by uttering Arabic prayers and walking around a scaled-down model of Islam’s holy cubical structure, usually covered with fabric that emulates the kiswa — the black cloth embroidered with Quranic verses that enshrouds the original Kaaba in Mecca.

Within school settings, this practice has been praised as an effective form of experiential learning to teach young pupils some basic tenets and practices of the Islamic faith. In other settings, especially regarding e-fatwas issued by Salafi clerics in Saudi Arabia, Kaaba models are reproached as a “reprehensible innovation” for several reasons, including that they might become objects of religious veneration in place of the actual Kaaba and/or reduce emotional attachment to the original sacred structure. In other words, it is a make-believe pilgrimage to Mecca tethered to a material simulacrum of the Kaaba. Just like Zuckerberg’s virtual world filled by avatars, it is, once again, lambasted as not the real thing. And while there is greater acceptance of pedagogical replicas among clerics, the desire to access the Kaaba via models and the metaverse — not to mention Kaaba playsets for children and other hajj-related craft activities — promises to grow and diversify in the future with each new technological invention and arena of practice.

Consumer culture and the tourism industry offer further opportunities to scale up the sacred, all for financial profit. Indeed, beyond its doctrinal centrality and social-emotional aspects, pilgrimage is big business in many faiths and traditions. Within the sphere of Islamic pilgrimages, experts estimate the hajj alone is expected to generate $150 billion in revenue for Saudi Arabia over the next five years. In the holy city of Mecca, restaurants, hotels and shops enjoy seasonal spikes in sales, while in Medina, the newly opened International Fair and Museum of the Prophet Muhammad’s Biography and Islamic Civilization offers visitors an immersive experience, as well as a variety of devotional souvenirs for purchase in its museum store and through its website. Among such mementos are children’s prayer rugs depicting the Kaaba’s door cover, the prayer niche (“mihrab”) of Muhammad’s mosque in Medina and the Kaaba’s Black Stone, the latter at the center of the current controversy about virtual reality and the budding metaverse.

Hajj objects and souvenirs should not be considered only a late capitalist phenomenon, however. They stretch back centuries and involve a range of visual representations and material iterations, from illustrated pilgrimage certificates to depictions of Mecca and Medina in mosques onward to modern religious merchandise such as watches, snow globes and lamps of the Kaaba that sell especially well during Islamic religious holidays. During these “seasons of demand,” devotional commodities become popular and can trigger expressions of piety. The same, it can be argued, holds true for a virtual hajj, which propels the pilgrim on a course that disperses the sacred into a simulated — and hence wholly “other” — realm, generating both excitement and anxiety along the way.

Islam’s sacred sites, especially Mecca and Medina, “circulate” through material representations, visual simulations, architectural copies and citations, and material artifacts such as embroidered kiswa panels, sacred soil samples, Zamzam water bottles and relics of Muhammad. The businesses and institutions that partake in this transmission process are many, involving individuals and companies as well as mosques and museums. While the latter two have tended in the past to function as discrete institutional entities, today they are merging into one. As a result, mosque-museums are at the confluence of cultural and religious spheres, bringing tourism and pilgrimage closer together. Just like reality and the metaverse, the zones of activity for mosques and museums in the Islamic world are starting to overlap in both promising and problematic ways. This is especially the case for the growing hybrid institutional entity known as the “museum of Islamic civilization.”

Some contemporary mosques retain their original function as sites for congregational prayer while concurrently tipping their hat to Islam’s holiest cities. Such is the case for the GOSP Mosque that opened in Istanbul’s Gebze Organized Industrial Zone in 2015. Its citational strategies include a cubical structure, jet-black stone and inscribed bands that recall the Kaaba and its kiswa, while the gold cupola seems to make an oblique reference to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This aesthetic mode transcends the mimetic and responsorial within architectural practice to activate larger metaphors, including, quite possibly, the imagination of Gebze as a new consecrated commercial site that “conglomerates” imports in Turkey, in both finance and piety. The mosque’s stylish, self-confident look also highlights the wealth and influence of Turkey’s devout business class.

At the apex of this political structure, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has undertaken colossal domestic building projects, the latest of which is the Islamic Civilizations Museum that opened in April 2022. This museum is part of a complex that includes a neo-Ottoman mosque perched atop Istanbul’s Çamlıca Hill. Despite its function as a museum and its location within a mosque complex, the Islamic Civilizations Museum falls under the aegis of the Directorate of National Palaces. This strategic bureaucratic categorization, hastened by a presidential decree, allowed for the transfer of about 800 objects from other Turkish collections in order to fill 110,000 square feet of display space in the new museum. Besides religious items, scientific instruments, weapons, ceramics and coins, its enclosed area includes digital models and high-tech projections as well as the sounds of prayer, pious intonations and even battle grunts that drift throughout the galleries.

The relocated sacred Islamic objects include hajj-related items, especially kiswa fragments and keys to the Kaaba’s door, as well as Muhammad’s relics, such as his blessed mantle, sandals and several strands of hair. His “blessed hair” (“sakal-ı şerif”) in particular is the closest there is to a bodily relic of Muhammad, and so is considered latent with auratic power. In Ottoman lands, it was a treasured trust and served as a sacralizing object in the foundation of mosques across the empire. In addition, in the 19th century, Muhammad’s hair became a mark of the Ottoman Empire’s expanding territory, which included at that time the three Islamic holy cities of Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem. Through the museum’s narrative and display strategies, Erdoğan and his curatorial team in the Çamlıca complex stake a Turkish claim of custodianship for Islam on the global stage. Much like the Ottomans who collected Muhammad’s relics in Topkapi Palace, a former royal residence and administrative center turned museum and archive in Istanbul, they thus enter into a larger competition for global sovereignty.

The Museum of Islamic Civilizations, located in Istanbul’s Grand Çamlıca Mosque Complex, crafts and projects a Muslim sacred lifeworld through careful design by mimicking mosque aesthetics and acoustics. It is, however, not the first institution to exhibit “Islamic civilization.” Others came before it, including Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, whose Turkish/secular objects were emphasized above its Islamic/religious collections (this is no longer the case since the 2014 renovation, which inaugurated a new gallery dedicated to Muhammad’s relics). Falling within this genre is also Sharjah’s Museum of Islamic Civilization, opened in the United Arab Emirates in 2008. The result of a collaboration with the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin, the museum’s exterior cupola recalls the Dome of the Rock, while its interior includes exhibits dedicated to Islamic faith and history. These include an early copy of the Quran, a kiswa fragment and mosque models, as well as interactive tools made to appeal to the “touch-screen generation” and young Emiratis keen to connect with their Islamic roots and traditions. Here, too, the museum involves a search for identity involving both nationalism and Islam, itself a religion not bound by state boundaries.

As the museum studies scholar Carol Duncan stresses, this ritual aspect is a recurrent feature of public art museums. What is nonetheless innovative is the enthusiastic adoption of today’s most advanced digital technologies within the now-expanding Islamic museological sphere. Such technologies, including holograms and virtual reality, are central to the International Fair and Museum of the Prophet Muhammad’s Biography and Islamic Civilization. Opened in 2021, it is supervised by the Muslim World League, an international nongovernmental organization whose stated aim is to present “true Islam.” In its vision statement, the museum underlines its own mandate, expanding it to include Islam’s “pure image” as well. While the term “pure” is intended to refer to an uncorrupted form of religion, linguistically it also inches close to the metaverse, itself a wholly imagistic, dematerialized world. Indeed, much like the digital presentation of the Prophet’s mosque in Medina, a substantial portion of the museum’s content is composed of pixels flickering on 3D screens as well as films that bring to life a simulation of society at Muhammad’s time. Additionally, in its official video, the museum is touted as a means to defend Muhammad via soft power, to strengthen the bonds of fraternity and promote peace and tolerance across the world. As a form of religio-cultural diplomacy, these types of museums engage in competitive one-upmanship when it comes to who is allowed to represent Islam and how. They therefore raise questions more metaphysical than museological.

Mosques, museums and the metaverse are now crisscrossing in an increasingly virtual world. A mosque can be toured digitally, a museum can deploy stereoscopic imagery and have a mosque-like feel and the metaverse can encompass all. The recent blurring of these spheres reveals that the supposedly distinct divide between material reality and digital artifice is wilting away, spurring inventions on the one hand and injunctions on the other. Beyond technological and doctrinal issues, one question that remains is: How does one account for the place of the imaginary or nonreal within Islamic emic traditions, and what is its potential future trajectory? This query can set into motion some “meta” musings.

In the European philosophical tradition, the problem of the simulacrum is essentially a Platonic one, as it involves a likeness that sheds the qualities of an original object. This difference, as the philosopher Gilles Deleuze points out, is of essential dissimilitude. In some cases, as scholars have argued, the simulation becomes truth, killing its own model. Moreover, in replacing material reality, simulated perceptions and fictional worlds become “realer than real” — an uncanny mimicry that involves a process of epistemological deception and existential replacement.

Digging back in time, the simulacrum has held a strong place in Islamic dream theory for centuries, gaining further traction in the modern era with technological advances from the moving image to the metaverse. In classical Islamic oneiromantic (dream) thought, the dream realm is a “real reality,” made by God and not the individual. As a “world of similitudes” (“alam al-mithal”), this transcendent reality contains images or likenesses that, albeit immaterial, are ontologically authentic and perceptually intelligible. This historical Islamic “world of similitudes” provides a future opportunity as a premodern matrix for approaching the metaverse as an image-filled, intangible dimension that does not necessarily seek to replace reality with deceit, fact with fiction, the primordial with the phantasmagoric.

Similitudes (rather than simulacra) engage the metaphysical — the supremely disembodied — in a literal sense. Furthermore, they craft a dreamscape that invites its participants to draw nearer to the divine through not an external but rather an internal journey. The metaverse hajj, if it ever does take off, could be couched in positive terms as a journey of the heart (“safar al-qalb”). Central to the Sufi tradition and connected to the notion of the “Kaaba of the heart,” this spiritual movement aims to activate the “other eye,” shifting perception from sight to insight. Like the mosque and museum, the Muslim metaverse could function not as a deceptive simulacrum prompting bans but rather as a lofty dreamscape, catapulting Islamic metaphysical thought into a whole other dimension.