On Jan. 12, 2021, the Israeli military launched some of its most intensive strikes to date in Syria. Over several hours, perhaps two dozen sites of Iranian-linked armed groups were hit over a vast territory in the Deir ez-Zor region near the Iraqi border. At least 57 militants were reportedly killed. Local communities did not report a single civilian casualty.

Four months later, the might of the Israeli military targeted a very different location.

On the night of May 15, a series of airstrikes hit the Al-Rimal neighborhood of central Gaza City. At least 44 civilians reportedly died. Multiple families were nearly wiped out after taking shelter in a neighborhood previously thought to be safe. Some Hamas militants may also have been killed in underground tunnels, the announced target of the strikes by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), though this remains unclear.

The death tolls on those nights were not an anomaly — they form part of a clear trend. The Israeli military has fought two largely aerial campaigns in recent years. One is a yearslong campaign to prevent the Iranian military and its allies from entrenchment in Syria, the other a brief but fierce war with Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza in May. The effect on civilians could hardly be more stark.

New research by Airwars has found that up to 10 times more civilians were killed in 11 days of bombing in Gaza than in the entirety of Israel’s eight-year campaign in Syria.

In Syria, several hundred secretive Israeli strikes since 2013 have likely killed as many as 40 civilians. Rough tallies suggest hundreds — and likely thousands — of Iranian and Syrian military personnel and militants of other nations were killed in these strikes. Civilian casualties from the Israeli campaign appear to be dramatically lower than those resulting from other foreign powers operating in Syria — including Russia, Turkey and the U.S.-led coalition.

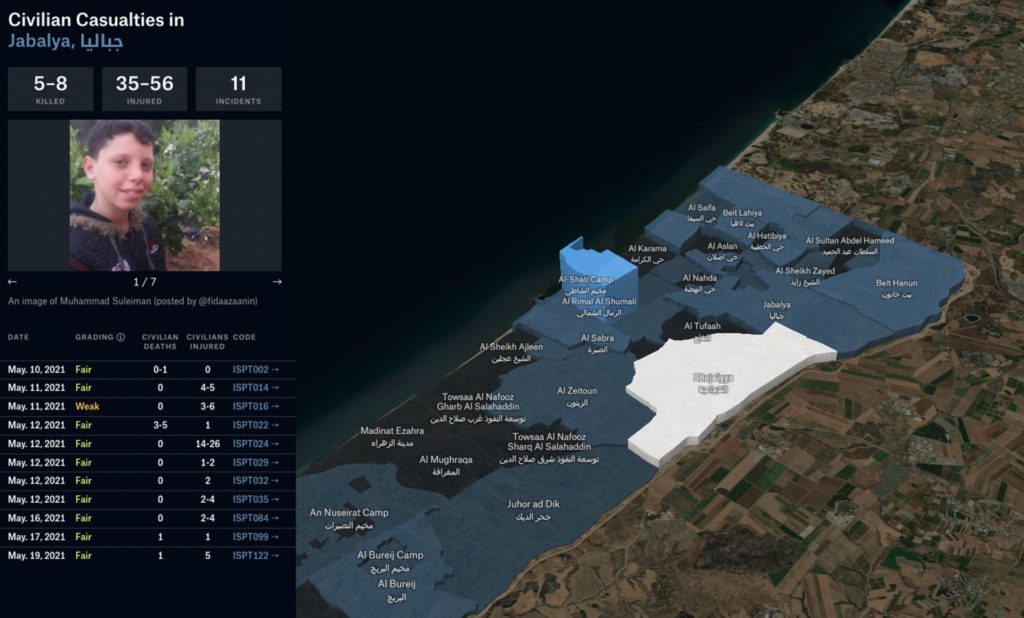

In Gaza the civilian-militant ratio is reversed. Between May 10 and 21, from 151 to 192 civilians were likely killed by Israeli airstrikes, according to a comprehensive review of local community reporting by Airwars. While this research didn’t estimate the number of militants killed, Israeli rights group B’Tselem put it at 90.

The Israeli actions in Gaza and Syria are usually thought of separately — with comparisons between the two rare. But how did a military that runs such a careful campaign in one theater end up killing so many civilians in just a few days in another? Our research pointed to three main reasons for the discrepancies.

The first is the type of targets chosen by the IDF in the two contexts. Israel’s targeting system bears many similarities to that of its closest ally, the United States. In fact, Israeli military lawyers pioneered the legal justifications for the targeted assassinations that later became a hallmark of the war on terror.

Until 2000, Israel legally considered Palestinian opposition a matter of law enforcement, said Daniel Reisner, then head of the Israeli military’s International Law Department. But following the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising, or intifada, the Israeli military effectively invented a “hybrid” model to apply the laws of armed conflict — normally meant to apply only between states at war — to the West Bank and Gaza.

Craig Jones, a lecturer at Newcastle University and author of a recent book on Israeli and U.S. military lawyers, said by expanding the concept of “direct participation in hostilities,” Israel effectively invented a new category of potential target between civilian and combatant — allowing it to justify a widespread campaign of targeted assassinations.

“Essentially, once a Palestinian ‘participates’ by the broad Israeli standards, he or she cannot put down arms and remains targetable even when resting at home,” Jones said.

Reisner recalled that U.S. officials initially criticized the policy but after 9/11 “started calling for advice.” Later U.S. official justifications for drone strikes included lines lifted almost directly from Israeli policy, he said.

This legal justification allowed for more freedom in targeting Palestinian militants in their homes. While potential civilian harm still needed to be considered and precautions taken, it was accepted by the Israeli system that hitting a militant at home was potentially justified.

When the Gaza conflict started on May 10, the IDF would have had dozens of targets that had been preapproved — meaning they had already been through legal and military review.

“The IDF would have taken out of its drawers plans that were pre-prepared and reviewed legally,” said Liron Libman, former head of the International Law Department at the IDF. “But then every plan is just the basis for an order. To turn it into an operational order, you still need to assess the information again.”

It seems likely that many of those preapproved targets were the homes of militants.

Airwars tracked 17 locally reported incidents in which militants were explicitly targeted in residential buildings and civilians were killed or injured. Most took place in the first four days of the conflict, suggesting that they were in a preapproved target bank.

In those 17 incidents, local reports found that from nine to 11 militants were killed but also from 27 to 33 civilians, with more than 100 injured.

In one incident on May 13, four civilians were killed and 15 more, including seven children, were injured. The target was a three-story house in the Al Jeniya neighborhood, where four families lived. One of the dead, Raed Ibrahim al-Rantisi, was identified by the al-Qassam Brigades as one of their fighters. The family had gathered for Eid dinner.

In Syria, such incidents are rare, though not unheard of — such as when a Palestinian official and his family were killed in a strike in central Damascus in November 2019. But in general, strikes in Syria seem to target militants at exclusively military targets such as weapons warehouses close to land borders. Some of the civilian harm associated with Israeli strikes may even have been a result of Syrian air defense missiles missing their targets and hitting civilian homes.

The IDF’s practice of striking homes in Gaza also contributed to the high percentage of children killed, with more than one-third of all civilians killed there reported to be children. In Syria the figure is around 10%.

Likewise, when Israeli forces killed a civilian in Syria, more than 70% of the time they also harmed a militant, whereas in Gaza that ratio was in the 30% range.

“In Syria we bomb military targets, while in Gaza we strike civilian areas, so we end up bombing families,” said Yehuda Shaul, of the Israeli human rights organization Breaking the Silence, which is made up of former IDF military personnel.

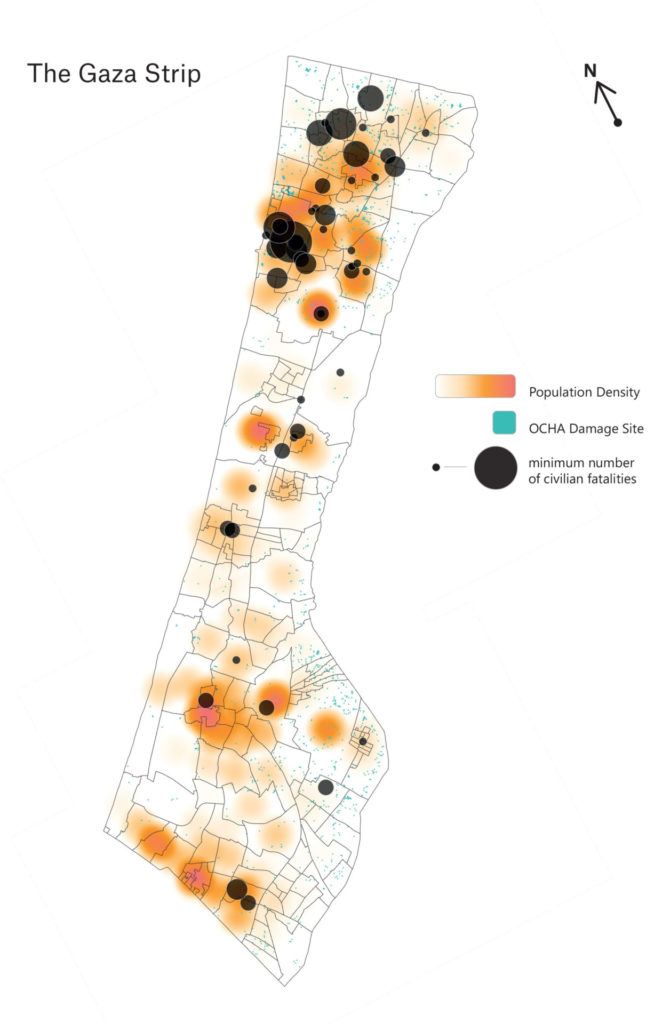

A second key factor that helps explain these very different outcomes for civilians in Syria and Gaza is population density. Gaza is among the most heavily populated territories in the world, which dramatically increases the likelihood of civilian casualties and damage to civilian infrastructure for every strike carried out.

We mapped every reported civilian harm incident in Gaza and every recorded strike location tracked by the United Nations, against population density.

Even within Gaza, civilian casualty incidents were clustered around areas of relatively high population density, such as in Gaza City to the north.

“Unlike in past wars, in May the Israeli military started its bombardment by hitting heavily populated areas and high-rise buildings,” said Yamen Al Madhoun, fieldwork director at the Gaza-based Palestinian rights organization Al Mezan. “Normally, people flee the perimeter areas where Israeli troops are stationed [and go] to schools and relatives’ homes in cities. But if civilian areas are the primary target, where can people go?”

Population density may also have provided some victims with a false sense of security. On May 12, airstrikes on the Tel al-Hawa neighborhood apparently targeting Hamas’ military wing destroyed two residential buildings. Reema Saad, who was four months pregnant, was killed alongside her two children and husband. The family had decided to stay in their apartment because they believed the densely populated neighborhood would be immune from strikes, Reema’s mother Samia told Middle East Eye.

Samir Zaqout, Al Mezan’s deputy director, said civilians had no idea how best to stay safe. “Fear, panic and confusion spread among the population. There were no taxis or transportation, so people were carrying their possessions and sometimes other family members while fleeing on foot.”

The Israeli military frequently notes that Hamas has placed military infrastructure in civilian neighborhoods in Gaza City, pointing to alleged tunnel networks as violations of the laws of war. Israeli officials also argue many of the more than 4,000 rockets fired by Hamas and Islamic Jihad from Gaza came from heavily populated neighborhoods.

But critics point out that hitting such neighborhoods overwhelmingly leads to civilian harm.

“Israeli authorities have shown an utter disregard for civilian life,” Omar Shakir of Human Rights Watch said. “They have a quite loose definition of what is a ‘military target,’ and they have consistently bombed in heavily populated neighborhoods without considering the civilian ramifications.”

“The rules and principles found in customary international humanitarian law to protect civilians should be followed,” Zaqout said. “Israel’s high-level military technology enables its forces to do so — to ensure the lawfulness of a target prior to attack. If circumstances are unclear, the Israeli military should presume people and objects normally dedicated to civilian purposes to be civilian.”

Even in Syria, the trend is noticeable. While the scale of civilian harm from IDF strikes is far lower than in Gaza, it is still overwhelmingly located in heavily populated areas, particularly the capital of Damascus — where around 45% of the estimated civilian harm occurred. In rural Deir ez-Zor Israel has carried out extensive strikes for more than five years, killing hundreds of militants and Iranian and Syrian military personnel along the way, without a single credible local allegation of civilian harm.

By contrast, both the U.S.-led coalition and Russian forces have caused often devastating numbers of civilian casualties during their own campaigns in Syria — primarily driven by extensive strikes on urban centers.

Such concerns chime with widespread calls for limits on the use of explosive weapons in populated areas. A U.N.-backed campaign now involving more than 120 nations — to forge a political statement that could help limit explosive weapons use in urban areas — is being led by Ireland, though so far no major military powers have fully thrown their weight behind it.

A third possible factor helping explain why outcomes for civilians differ so radically between Israeli campaigns is one that is harder to prove — that the Israeli military has different, and more expansive, rules of engagement (RoE) for strikes in Gaza compared with Syria. Such RoEs govern when militaries are allowed to use force and, in the event that a strike is likely to kill civilians, determine how many casualties are deemed “acceptable.”

There are no internationally agreed-upon rules of how many civilians can be killed in a strike — international law requires only that it be “proportional” to the military advantage gained. At one point during the presidency of Barack Obama, U.S. generals in Iraq were allowed to carry out strikes they expected might kill up to 10 civilians, whereas the same figure in Afghanistan was at times set at just one, given the political sensitivities of civilian harm.

Multiple sources said the Israeli military does not internally quantify these “acceptable” tolls quite so explicitly, preferring instead to be “very context specific,” as Libman, now research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, said. The country has never released its RoEs for Syria or Gaza, and it is unlikely to do so.

A recent study found that Israeli military officers in general were significantly more conservative in their view of acceptable levels of civilian harm in discussions on proportionality as compared with their U.S. counterparts. The study, by universities in Israel, the U.S. and the U.K., found that in an imagined case of targeting an enemy headquarters, the median number of civilian deaths that U.S. officers were willing to tolerate in order to achieve military gains was 175, while Israeli officers were willing to accept 30 such casualties.

The IDF also likes to highlight its policy of warning civilians in Gaza before some airstrikes, a practice not widely adopted by other military actors. Yet these are the exception rather than the rule — in the 136 civilian harm incidents Airwars researchers tracked, the vast majority of targets had reportedly received no warnings.

According to Breaking the Silence, when there is imminent threat to populations, Israeli militaries are willing to carry out strikes that threaten civilian lives. “When there is even the slightest threat to Israeli lives, concern for Palestinian civilians all but goes out the window,” Shaul said.

Reisner didn’t dispute that the calculations were different in Gaza. “If I see an enemy about to fire a rocket at an Israeli city, the proportionality calculation would be different than if I saw the same individual at home knowing he is planning an attack in three days,” he said.

“I can legitimately kill many more civilians — it is a horrible sentence, but [it is the reality].”

Hamas and Islamic Jihad also posed a far more imminent threat than Iranian groups in Syria, said Amos Guiora, a professor at S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah and another former senior Israeli military lawyer. “With the Iranians you can afford to wait for the right time,” he said.

Politics may also play into it. Guiora said that the potential for a political fallout from a strike in Syria could also encourage caution. Israel has long had de facto control over the Palestinian territories but open involvement in Syria could risk a backlash at a time when Israel has secured landmark deals with Arab states including the United Arab Emirates.

“An unacceptable number of civilian deaths opens the door to blowback and bounceback, in the court of international opinion,” he said.

“Maybe from a geopolitical perspective, extra caution is necessary in Syria.”