During the turmoil of the Arab Spring, the world came to know heroes of the various groups taking part in the fighting. For the jihadists of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), the historical heroes were the early Muslim conquerors from the first days of Islam’s emergence in the Arabian Peninsula. For the Iranian regime and its Arab Shiite proxies, they were the 12 Imams descended from the Prophet Muhammad. In Turkey, they were the Seljuks and other Turkic tribes who migrated to Anatolia in the 11th century CE, as well as the earlier Arab conquerors. In all cases, the heroes and their stories were inseparably linked to the spread and transformation of Islam, a fact that impels them to continue in their predecessors’ footsteps today.

With Kurds, this is simply not the case.

The heroes that have endured over the centuries within Kurdish society have been stripped of any Islamic associations. Kurds’ perceptions of their historical heroes bear no relation to any Islamic inclinations, neither moderate nor extremist. It is a wholly secular mythology. I believe this is the reason Kurdish society has historically been less susceptible to extremist religious ideas. In the 19th century, Western travelers to Kurdish regions wrote of seeing Kurdish men and women interacting easily, in contrast to their observations in nearby Anatolia, Mosul, and Baghdad. In his “Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan, and on the Site of Ancient Nineveh,” the British traveler Claudius Rich recalled a journey to Kurdistan in 1820, during which he noted the great autonomy enjoyed by Kurdish women.

The specific mythical narratives that shape the Kurdish identity cannot easily be merged with any others in the neighbourhood, even those with which there is a common religious denominator. Rarely would a Kurdish fighter compare himself to, say, Khaled ibn al-Walid, the Arab Muslim commander who conquered Damascus from the Byzantines in 634. Far more inspiring to a Kurd would be a battle cry such as: “Stand firm, O descendants of Emîr Xan Lepzêrîn!” or “Do not retreat, O children of Darwish Avdi!” These are the deep forces that fire the spirit of Kurdish nationalism. It would be no exaggeration to say they have done a great deal to shape Kurds’ political character and the way in which Kurds wage their battles, both military and political.

Religious ideologies in their Islamist, Salafist, or jihadist variations exist but in narrow and elitist Kurdish circles, with almost no popular base. Kurdish communities tend to be traditional, and their religiosity is largely Sufi, linked to either the Naqashbandi or the Qaderi orders. These Sufi traditions are also closely tied to Kurdish nationalism, independent of Arabic, Persian or Turkish cultures. Kurdish Sufism even produced its own folkloric stories, such as Mem and Zain (the Kurdish equivalent of Romeo and Juliet) and the Basket Seller (about a Kurdish prince who committed suicide to escape sexual advances by a princess). The stories are highly popular among Sunni Kurds, the supposed targets of jihadist proselytization, and such powerful folkloric and spiritual foundations prevented the spread of Salafist or Islamist ideas.

As a child, my hero was always (and still is) Darwish Avdi (Dewrêşê Evdî in Kurdish), as described to me by my father, before I later heard the story told with different details by Kurdish singers. Likewise, the strongest and most beautiful horse for me was Hadban, which Darwish rode in battle. No matter where one goes in the Middle East’s Kurdish regions — from Dersim in the north to Erbil in the south; from Kermanshah in the east to Efrîn in the west — the main characters are similar.

In the late spring of 1906, the British politician and traveler Mark Sykes sat in a large tent during one of the five voyages recounted in his book, “The Caliphs’ Last Heritage: A Short History of the Turkish.” Though little known today in his native Britain, Sykes’ name would go on to become more memorable to the peoples of the Middle East than Napoleon Bonaparte, Winston Churchill, and George Washington. In 1916, he was associated with the British-French-Russian accord, commonly referred to as the “Sykes-Picot Agreement,” blamed ever after by Middle Easterners for the partition of their once-united land.

In this tent, Sykes met the most important leader of the territory between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers (a region known as “Jazira”), Ibrahim Pasha Milli, who led a unique tribal alliance he inherited from his ancestors. The Mîlan confederacy, named after the Kurdish tribe that led it, was multiethnic and multireligious, containing Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen tribes, with Muslim, Yazidi, and Christian members. The bulk of the territory over which it held sway corresponds to the territory controlled today by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), as well as the area held by Turkish-backed forces following Ankara’s 2019 “Peace Spring” military operation. In its Kurdish leadership and pluralistic composition, it resembles the SDF today.

The quasi-state founded by this Mîlan confederacy dates back to the second half of the 18th century, though the tribal alliance itself is much older. Its innovation was to convert the Kurdish-Arab-Turkish rivalry into an opportunity. The first multiethnic tribal alliance was born, transcending the traditional tribal model of a purely dynastic hierarchy. In this way, the Mîlan principality was able to create armed units made up of separate divisions for Arabs and Kurds, for the most part, as well as Yazidis, who were well-represented within the leadership since the Yazidi community was much more geographically widespread than it is today. There were Yazidis in Suruç, in what is now the Turkish province of Şanlıurfa; in western Mardin; in Efrîn, north of Aleppo; and in various parts of the Jazira region. It was not possible for one single national or religious group to establish political hegemony over such areas. The Mîlan leadership model was a means of managing diversity and protecting the existence of all components of this tribal alliance, extending from southern Diyarbakır to Mount Abdulaziz in the Syrian province of Hasakah, and from the eastern banks of the Euphrates to the western banks of the Tigris.

When Sykes reached the outskirts of the town of Ras al-Ayn, he was met by Ibrahim Pasha himself. Sykes described the encounter in “The Caliphs’ Last Heritage”:

“On our arrival the Pasha, whom I had visited before, came out to meet us, and embraced me after the Bedawin fashion — that is, by kissing my right shoulder. I was immediately led into the great tent, which was supported on over 100 poles and measured 1,500 square yards of cloth. Coming from the glare of the mid-day sun it was at first difficult to distinguish anything clearly in the recesses of this vast tabernacle, but at the farther end about 150 men were standing around the low divan on which Ibrahim sits. He led me to the divan, which was placed before a camel-dung fire, on which stood the usual number of coffee-pots.”

It’s surprising that Sykes did not write about the Darwish Avdi epic in his chapter on the Jazira and Kurdistan regions. Perhaps Ibrahim Pasha avoided telling the story, due to the embarrassment it involved for his grandfather, Timur Pasha (more popularly known as Tamr). The epic began under the very tent in which Sykes and Ibrahim Pasha were then sitting, more than a century earlier.

Historical sources tell of a campaign organized by the governor of Baghdad, Sulayman the Great, in 1790. The governor hailed from a family of Georgian origin, dubbed the “Mamluks,” indicating soldiers purchased from faraway lands. This family ruled for nearly a century, up until 1831. The 1790 campaign was aimed at the center of the Mîlan principality, in Veeranshahr, in today’s Şanlıurfa province, when Tamr Pasha was the leader of the tribal confederacy. A contemporary source tells us the following:

“In this year, (Sulayman the Great) fought against Tamr Pasha and defeated him, installing in his place as head of the Mîlan his brother, Ibrahim Pasha.” Prince Tamr Pasha had previously been renowned, having held off attempts by the governors of Diyarbakır and Şanlıurfa to defeat him. He controlled a portion of the Silk Road between Mosul and Aleppo, imposing fees on the convoys that passed through. On one occasion, during the defeat of the Diyarbakır army, Tamr Pasha’s spear was broken in battle. His response was to demand a payment of 10,000 piasters from the people of Diyarbakır every year thereafter. His principality had no fixed base, but rather revolved around a tent that moved up and down the Silk Road.

Things changed, however, when the Ottoman Sultan Selim III personally demanded that the armies of the provinces surrounding the Mîlan principality be equipped in order to break it apart. A number of senior Mîlan tribesmen were killed, including one man named in Iraqi historical sources as Darwish Agha (Chief Darwish). This man is the hero of the Kurdish epic.

Contemporary historical sources downplay — perhaps intentionally — the great social unrest that occurred in the Jazira region in that period, due to the vast tribal movement from the Arabian Peninsula toward the more fertile pastures of the Syrian and Iraqi deserts at the time of the expansion of Wahhabism. The forces of nature (the search for rainwater, drought) combined with political factors (Wahhabist proselytization) to create a Bedouin population shift that caused unrest on the banks of the Euphrates. Some tribes fell, while others rose. The tribal configuration that prevails today in Syria and Iraq is a result of this period of unrest between 1790 and 1850, when the winners and losers became clear. Four tribes above all emerged as the key victors: the Egaidat, the Baggara, the Shammar, and the Mîlan. A fifth was the Yazidi in Sinjar.

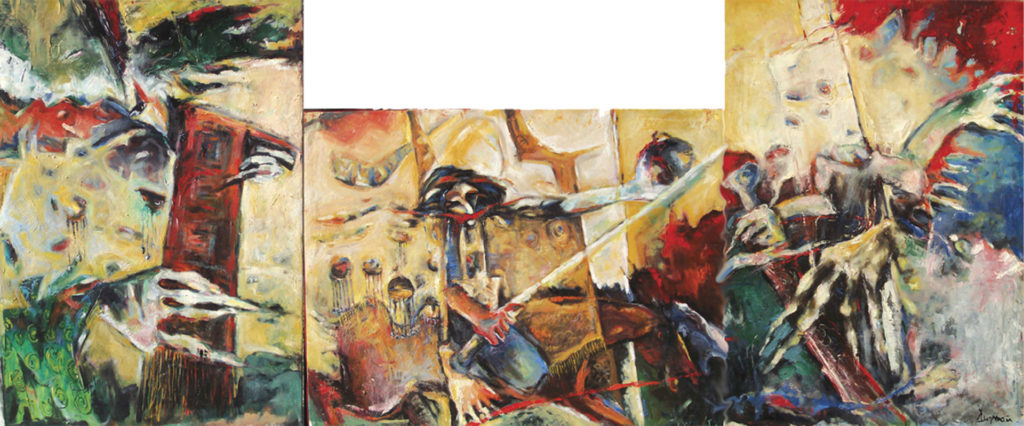

The Kurds captured this great upheaval in an epic tale starting in the tent of the Prince Tamr Pasha, who enacted an unusual tribal custom. He sent messages to all the tribal leaders of the Mîlan confederacy, asking them for an emergency meeting. They duly appeared and sat all together under the large tent described in great detail in Kurdish folk songs. Among the attendees was a representative of the Yazidis, Darwish Avdi, a handsome young man in his early 20s who was in love with the Muslim daughter of the Mîlan prince, named Addoula. It was a love doomed from the start, since both Islamic law and social custom forbade a Muslim woman to marry a Yazidi man. Whenever the epic is sung, it is done so from the perspective of this beautiful young Kurdish princess.

Prince Tamr Pasha ordered that cups of coffee be poured, as per Bedouin tradition when hosting guests. Coffee has its particular rituals, however, and can sometimes represent a transformative moment in social relations. As a servant poured the cups, Pasha said the enemy had equipped a large army that was heading their way, an army comprising 1,700 brave warriors from the Arab Qays tribe, as well as Turkmen. Whoever repelled this invasion, he said, would win the right to marry his daughter Addoul, in addition to a large share of the spoils.

Darwish Avdi received Pasha’s coffee cup. Here, the song takes on a tragic dimension from the perspective of Addoul, who begs her lover to refuse to go, indicating that her father seeks to get rid of him by this means. An ardent dialogue takes place between the two lovers, both of whom seem to realize early on that Darwish is destined to die. Despite this, the young Yazidi is determined to answer the call of duty to defend his land and honor. The songs also contain a heavily erotic dimension, with Addoul trying to dissuade her lover from leaving by describing her body and her breasts, the description of breasts being a common trope in classical Kurdish songs.

The epic thus sheds light on two further elements: the oppression of Yazidis by the Muslim Kurdish pashas and the struggle over the desert between the Kurds (both Muslim and Yazidi) and the Arabs.

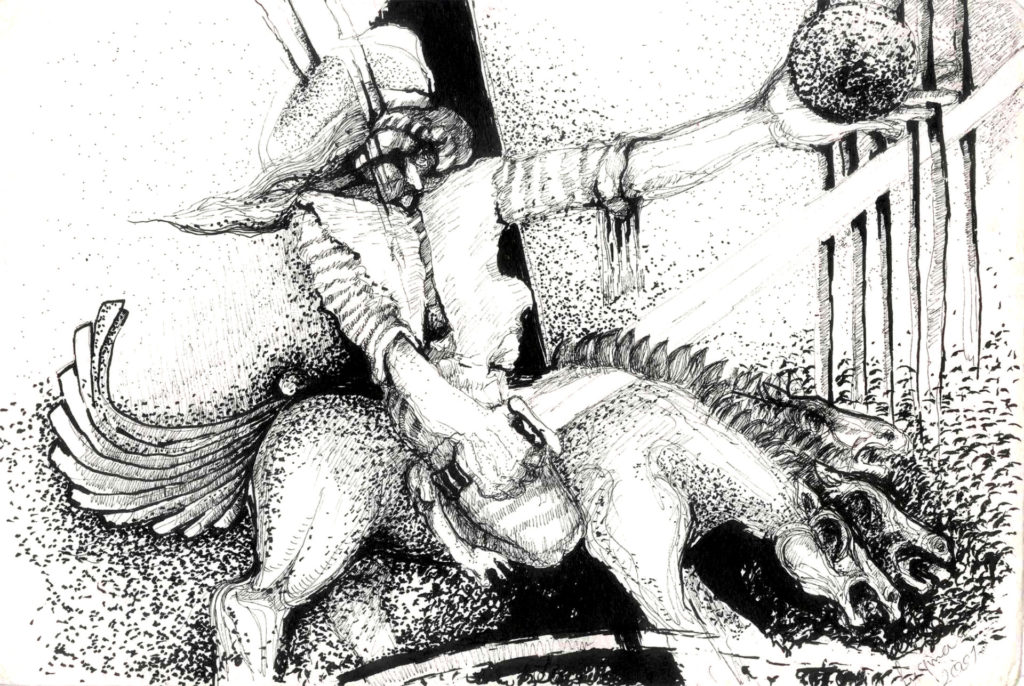

Darwish had previously developed a close friendship with the Arab leader of the Qays tribe, named Afar. Darwish was often in the habit of launching solo raids on caravans, say the songs. On one occasion, he encountered a flock of sheep guarded by horsemen, who happened to be from the Qays tribe, led by Afar. Darwish challenged him to a duel, and Afar accepted, but was unable to defeat Darwish, until he told his friends watching to push the sheep toward him. They did so, restricting Darwish’s movement in the process, until he was overcome. The two young men then swore a pact of brotherhood, writing their names on a stone and burying it in the soil. Afar even gifted Darwish his purebred horse, named Hadban.

Thus, in accepting Pasha’s coffee cup, Darwish was not only accepting the cup of death but also agreeing to fight a last battle against his closest friend. The epic describes 12 Kurdish Mîlan knights setting off for the battle — six of them Muslim, and six Yazidi — as though these 12 alone made up the entire fighting force.

Darwish had fallen into a trap. This is the interpretation taken by Yazidi narrators, which prevails to this day. He had fallen for the ruse of the Kurdish Pasha, who wanted rid of Darwish because he had dared to declare his love for Pasha’s daughter Addoul, setting tongues wagging about them. In a sense, the story represents the perennial dilemma of the Yazidis: Do they respond to their betrayal? Or do they lick their wounds and join their fellow Kurds in repelling the foreign invaders?

Afar of the Qays was reluctant to fight when he learned his friend Darwish would be the one leading the Mîlan forces. Yet when Darwish heard of this, he was insulted and told Afar he could not turn away without fighting this war, nor could he return defeated. If he were to be beaten, Afar would be doing him a service by killing him. The Arab commander was determined to avoid this outcome, but his knights fought ferociously, even though Darwish inflicted heavy losses upon them. They decided to set a trap for him, luring Darwish to a hill called the “Hill of the Mice,” with which he was unfamiliar. At the hill, they dismounted their horses and climbed its slopes on foot. Darwish made the mistake of following them on horseback, causing the horse to stumble and trip in the mice’s burrows. Darwish fell off Hadban and broke his bones, unable to move. The enemy knights were about to pounce on him until Afar ordered them back.

As Darwish lay breathing his final breaths, Afar picked him up and carried him to the top of the hill. Resting his dying friend’s head on his knee, Afar said to him, “My brother, how many times did I beg you to go home, and you replied that you couldn’t go back on your decision, after drinking the cup for the sake of the Pasha’s daughter? Do you see now what’s happened to you? You’ve killed all your friends, and killed yourself, and your only brother, all for this Addoul. Now you lie dying, and you will never see Addoul again, nor your mother and father. What have you gained in this war of yours?”

Darwish responded with a final request. “Brother Afar,” he said, “You know that those currently on their way to us include the enemies of myself and Addoula. I am certain Addoula will come with them. They include Mîlan members, and some would love to mock me. I beg you, arrange my clothes and cloak, and clean the blood off my face, and make it look as if I never fought.”

Afar fulfilled the Yazidi prince’s request, sacrificing his own reputation for the sake of friendship. For if it appeared that Darwish hadn’t fought, it would mean he had been betrayed and assassinated; something Afar was prepared to pretend in order to embellish his friend’s death. (Another account has Darwish asking Afar to kill him before backup from the Mîlan and the Yazidis arrived because he didn’t want to speak to anyone in his wretched state.)

The final scene of the epic narrates Addoul’s arrival, accompanied by the Mîlan forces. Placing Darwish’s head on her knee, she weeps and rebukes him for what he has done. In some versions, he is still alive at this point and begins flirting with her despite his condition, and she speaks to him through her tears until he passes away.

Certain popular epics take on revolutionary symbolism. The Darwish Avdi epic has furnished the Kurdish spirit of resistance with a reservoir of romance and a spur to individual action at times when it is almost impossible to do anything. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan once alluded to this when he was in Rome, after departing Syria on the run from the Turkish authorities in 1999. At one point, he met with prominent Kurdish artists, including the most famous singers of the Kurdish revolutions, Şivan Perwer and Gulistan, accompanied also by the Kurdish politician and journalist Mahmûd Baksî. Öcalan spoke about his relationship with the Darwish Avdi epic and how it affected the course of his life. He had heard the song while lying in hospital in Rome and was amazed by the style of its telling. He requested that the epic be supported artistically. “When one of our fighters stands in front of a mountain, his path blocked by snow, the determination he will derive from Darwish Avdi will provide him superhuman energy.”

In his book, too, which he wrote in İmralı prison, titled “The Kurdish Cause and the Solution of the Democratic Nation,” he again reflected on the epic, providing a new reading of it, suggesting that the story of Darwish and Addoul points to “the desperate resistance of the Kurdish spirit embodied in the last generation of Yazidis aspiring to steadfastness in the face of extermination.” Darwish’s wandering between Mount Sinjar and the Mosul plain was interpreted as representing “heroic resistance to Arab-Islamic feudalism.” Öcalan also opined that Darwish falling off his horse on the Hill of the Mice symbolized the fall of an entire history and society and the inflicting of deep wounds upon them. So affected was Öcalan by the story that he composed his first and only poem, which began, “Oh, to be on Sinjar’s summit with Darwish Avdi … Crossing the Mosul plain atop a white horse.”

Öcalan aside, the Kurdish national movement has helped deepen the heritage of the Kurdish resistance since the start of the 20th century. The stories existed before then, but it was at that time that they were given political dimensions serving to mobilize the resistance socially.

The Kurds have two kinds of heroes. The first are those of ancient Iranian history, when Kurds, Persians, and other Iranian peoples shared the state. This kind of evocation was seen when Kurdish exiles from Turkey in Syria founded a national political movement called Xoybûn in Beirut in 1927. The movement promoted the figure of Rostam, son of Zāl, as an early hero of the so-called Asian Aryan peoples. Rostam was immortalized in the “Shahnameh,” the first Persian epic written in poetic form, composed by Ferdowsi approximately 1,000 years ago. The leader of the Ararat rebellion, Îhsan Nûrî Pasha, who was also a Xoybûn member, made reference to Rostam during his leadership of the rebellion against the Turkish Republic between 1927 and 1931. This symbolic gesture was also designed to please the Iranian government, then turning a blind eye to the movement of Kurdish militants across its borders. The painful blow delivered to the revolution by Tehran in 1931, however, reduced such use of shared symbols for political ends.

The second kind of hero is the strictly Kurdish one, epitomized by Darwish Avdi. A shared historical symbol, he protects the bonds between Muslim and Yazidi Kurds. In recent years, in light of their experiences at ISIS’s hands, some Yazidi voices have tried to sever their psychological ties with Muslim Kurds, portraying their cause as one of a people distinct from Kurds. This feeling derives from what they see as the failure of Iraqi Kurdish forces to protect them, resulting in the abduction of thousands of Yazidi women, leaving a deep wound that will not easily be healed. According to these voices, Tamr Pasha’s betrayal of Darwish Avdi has been repeated.

At the same time, there are factors preventing this epic from pushing the Kurdish sects apart. Kurdish armed forces, such as the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the PKK, succeeded in opening a safe passage between Sinjar and eastern Syria, enabling the rescue of over 100,000 Yazidis, at a cost of some 300 fighters, according to the SDF’s commander-in-chief, Mazloum Abdi. In a poetic sense, this operation to rescue human lives served to rescue the epic of Darwish Avdi as well.

The legend is deeply embedded in the form currently taken by the Kurdish resistance. The 2014 battle of Kobanî between ISIS and the YPG was another example. According to statements I obtained after the battle, the forces’ leadership had granted the initiative to the small fighting group that had remained in Kobanî before the anti-ISIS coalition intervened. ISIS fighters had surrounded the town on three sides, with Turkey blocking the northern border. Fighters had the option to surrender and escape, however. The leadership gave them the freedom to choose. The small group who opted for death over surrender were reenacting the Darwish Avdi epic for modern times. Their defeat, had it happened, would have remained a source of pride and national inspiration for generations to come.

At present, this paradigm of resistance is deeply ingrained among the Kurds of Syria and Turkey in particular. In the past, it was more common among Iraqi Kurds, but this is no longer the case. In Iraqi Kurdistan, the recent defeats — against ISIS in 2014, and then at the hands of the Popular Mobilization Forces in 2017 — are unlikely to constitute material for any epics inspiring the Kurds of tomorrow.